The year is 1920. The Treaty of Sevres has just been signed on August 10, 1920 effectively ending the rule of the Ottoman Empire and breaking it apart into multiple fragments. The War to End all Wars has ended, so conflict should end, right? Nope. With the signing of the Treaty of Sevres and the Armistice of Moudros in 1918, started the buckling of the Ottoman Empire.1 Sensing the oncoming fall of the Ottoman Empire, different nationalist groups began to form, each one seeking self-determination by demanding a state for their own peoples. In this time, the Young Turks movement was born. Demanding a Turkish state was based on the principles of military strength, modernity, and Turkishness. Thus, the war of National Independence began and they foughtagainst Armenian forces who were also seeking statehood. Later the fight move against with the Greek military as they began to take Ottoman territory. Aided with the Soviets with a treaty signed in 1921, the war finally came to a close with the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923.2 After creating the Republic of Turkey, the Young Turks yearned to push out minorities or ‘non-Turkish’ people out of the area. The Young Turks pushed for the idea of a unified, homogeneous society that followed Turkish tradition, culture, and religion. These ideas came out of the Balkan Wars where nationalism had been used to eliminate non Turkish peoples from the Ottoman Empire. In response, Greece seized Turkish territories and began to discriminate against the Muslim minority. Both sides seized property and used deportations as a way to create a homogeneous society. During the fighting prior to the Treaty of Lausanne, Greek nationalists fled the region to Anatolia and Muslims from Greece fled to Turkey.3

The convention concerning the exchange of Greek and Turkish people is written as a separate convention with the same authority as if it were a part of the Treaty of Lausanne. As the title states, it deals with the Greek and Turkish peoples who were living in as minorities in these territories (at least in the eyes of the newly formed states they resided in).4 The people of Greek decent who live in Turkey were considered Greek and vice versa. The convention defined. This means that Turks who were a part of the Greek Orthodox religion must go to Greece and the same for Muslim Greek nationals who were to be sent back to Turkey. The exchange was also compulsory meaning it was required by law so even if the person was and has been a Greek national their whole life, but worshiped Muslim, they had to emigrate to Turkey. Even prisoners of war or criminals had to be exchanged as stated in article 6 of the convention stating that “in the event of an emigrant having received a definite sentence or imprisonment, or a sentence which is not yet definitive, or of his being the object of criminal proceedings, shall be handed over by the authorities of the prosecuting country to the authorities of the country where he is going in order to serve or receive the sentence.”5 Those who had to leave the country could not go back without the proper authorization from the Turkish or Greece government, respectively.6 Though, there were exceptions to the exchange. For instance, Greeks living in Constantinople (now Istanbul) and Muslims living in Western Thrace were unaffected by the exchange. The reason being, as stated in Article 2 of the Convention, all Greeks established before the 30th October, 1918, within the areas of the prefecture of the City of Constantinople, as defined by the law of 1912. Under that same article, it was noted that all Muslims established in the region to the east of the frontier line laid down in 1913 under the Treaty of Bucharest could remain.7

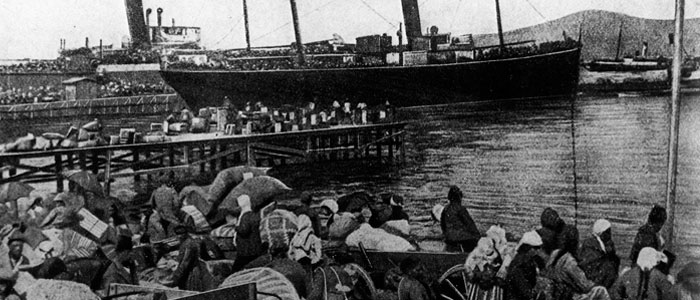

As of May 1, 1923, 700,000 people were removed from their native soil and made de facto refugees. The convention also confirmed the status of refugee for an additional 1 million displaced people prior to the convention during the Balkan Wars.8 These displaced peoples were allowed to take their property, but any immovable property, such as homes, had to be liquidated and given to the owner the amount it was worth. The liquidation process was up to the authorities and to the Mixed Commission. A Mixed Commission, as defined by international law, are instruments of arbitration that have been established by bilateral or multilateral treaties.9 The Mixed Commission, set up under Article 11, was created one month prior to the enforcement of the convention, was set up in Greece or Turkey and consisted of 4 members, each a part of a high contracting party, and an additional 3 from the League of Nations that did not take part in WWI (1914-1918). The Mixed commission had the power to set up smaller sub commissions made up of one Greek, one Turkish, and a neutral member in order to be considered valid and could be set up anywhere the Mixed Commission saw fit. In general, as stated in Article 12, the Mixed Commission had full power to take measures needed to execute the Convention and to decide all questions regarding the Convention.10 Though the Convention went into depth on the relocation of property and the powers of the Mixed Commission, it failed to list the practical matters. Practical matters being food, clothing, shelter, health care, and integration programs if any should be instated. Wording in the document also led to challenges to both nations,especially to some minorities that were neither Greek nor Turkish that neither country wanted. For example, the Greeks did not want the Albanians or the Roma (Gypsyies) and Turkey did not want the Armenians or Assyrians.11

The social and economic effects on both sides were significant. Unlike Turkey, Greece had large swaths of non arable land with a majority of the population engaged in agriculture even though it was not the most important economic activity. Even though Greece had incorporated fertile lands from Thessaly in 1881 and then again after the Balkan Wars, the additions of approximately 1.5 million new citizens, led to changes in the land tenure system. The Land tenure system varied from region to region in Greece with larger farm estates in the north. Fortunately, the Greek government made changes to the distribution of land since it was primarily based on social/economic class and decided to break apart larger estates in order to give land to peasants back in 1917. Hence, when the refugees arrived, there was an uptake in agricultural production.12 Greeks also played a role in Turkey’s economy through different industries such as factories and iron works, flour mills, along with smaller industries like tanneries, soap and dye works, box making for agricultural products, confectioneries, and beverages.13 Turkey lost these economic benefits when they lost 1.5 million workers. The reason these workers were so significant is that by 1919, Greeks owned 75% of large industrial plants more than any other group which included smaller home industries, small workshops, manufacturers, and factories. Greeks owned about 49% of all industry and crafts. When the exchange happened, Turkey tried to make up for these losses trying to fill the void the Greeks left behind. This, however, led to more competition between the Greek and Turkish economies.14

The social impact was mostly towards minority policy and nationalism prior and after the Treaty of Lausanne. Even though the Treaty itself safeguarded minority rights, over time that safeguard went against the changing ideas of nationalism. The process of nation building which at that time favored unitary and homogeneous constructions of national identity. The transition hit Turkey minority policy the hardest since it went from Ottoman plurality to a form of unitary nationalism under the Young Turks which centered on Turkish culture, language, and Muslim religion. Similar to this, the Greeks wanted to built a homogeneous community who spoke Greek with the official religion as Greek Orthodox. Both countries created assimilation programs based on these ideas of nationalism after the Treaty of Lausanne forcing minorities to follow the desired unitary model.15 Another change in social policy was the idea of minorities, especially in Turkey. The Turkish delegation at the time even debated with the Allied powers during the convention with the claim that there were no minorities in Turkey except non-Muslims. The Turkish delegation strongly pushed this standpoint since they believed that if a broader term were enacted, it would become a major security threat to their country since many Muslims in Turkey at the time were of different ethnic and lingual groups.16 The convention mapped identity based on religion rather than on actual ethnic or linguistic status.

The Greeks called this event the ‘Asia Minor Tragedy’ because they made up the majority of the displaced peoples with more than 1 million compared to 400,000 Muslim Turks who were displaced. For the Turks, this was seen as a unification of the Turkish peoples and a major victory for State of Turkey, but the exchange was wholly removed from the historical narrative for the Republic of Turkey. Even articles written by the late Omer Lutfi Barkan, known for his articles on comprehensive immigration policies and resettlement in Turkey in the late 1940’s, refrained from any critical examination of the Exchange.17 Refugees on both sides struggled to learn Turkish or Greek respectively and to adapt to the different lifestyles and cultures which impacted many families, but with no other option, they assimilated. However, in the 1990’s the refugees and their descendants were allowed to visit their ancestral towns. Projects to make up for the removal of peoples have been created on both sides to help ease the remaining refugees, especially the ones in Instanbul’s Tuzla municipality. On September 4, 2013, 90 years after the Population Exchange, some were able to go back to see their homeland. The project also invited people not affected by the Exchange to see the journey the refugees took from the Karakoy Cruise port in Istanbul to Kavala, a coastal city in Northeastern Greece. Its main focus, to raise awareness of the rarely mentioned exchange to Turkish citizens and to highlight the problems both communities had faced with the exchange.18 There are now reciprocal visits by both Greeks and Turks as part of a cultural project that is supported by the European Union and the Foundation of Lausanne Treaty Emigrants.19

.

- Brian Bonhomme and Cathleen Boivin, “Milestone Documents in World History: Exploring the Primary Sources that Shaped the World,” (Dallas: Schlager Group, 2010), 1280. ↵

- Europe since 1914:Encylopedia of the Age of War and Reconstruction, 2006, s.v., “Ataturk, Mustafa Kemal (1881-1938),” by John Merriman and Jay Winter” ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2014, s.v. “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations,” by Josephine Campbell. ↵

- Brian Bonhomme and Cathleen Boivin, “Milestone Documents in World History: Exploring the Primary Sources that Shaped the World,” (Dallas: Schlager Group, 2010), 1299. ↵

- “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations,” The American Journal of International Law 18, no. 2, (April 1924): 85 ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2014, s.v. “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations,” by Josephine Campbell. ↵

- “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations,” The American Journal of International Law 18, no. 2, (April 1924): 84. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2014, s.v. “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations,” by Josephine Campbell. ↵

- Dictionary of American History, 2003, s.v. “Mixed Commissions,” by Gregory Moore. ↵

- “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations,” The American Journal of International Law 18, no. 2, (April 1924): 88-89. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2014, s.v. “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations,” by Josephine Campbell. ↵

- Aytek Soner Alpan, “The economic impact of the 1923 Greco-Turkish population Exchange upon Turkey,” (METU, 2008), 38, 42-43. ↵

- Aytek Soner Alpan, “The economic impact of the 1923 Greco-Turkish population Exchange upon Turkey,” (METU, 2008), 80-83. ↵

- Aytek Soner Alpan, “The economic impact of the 1923 Greco-Turkish population Exchange upon Turkey,” (METU, 2008), 84, 92-93. ↵

- Nora Fisher Onar, “How deep a transformation? Europeanization of Greek and Turkish minority Policies,” International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 17, no. 1, (2010): 3-5. ↵

- Yesim Bayar, “In pursuit of Homogeneity: the Lausanne Conference, minorities, and the Turkish nation,” Nationalities Papers 42, no. 1, (January 2014):7-8. ↵

- Yildrim Onur, “The 1923 population exchange, refugees and national historiographies in Greece and Turkey,” East European Quarterly 40, no. 1, (Spring 2006): 45. ↵

- “Turks displaced in population exchange visit homeland after 90 years,” BBC Worldwide Monitoring, August 8, 2013. Accessed April 4, 2018. ↵

- Isil Ocal “The Great Population Exchange between Turkey and Greece,” Aljazeera World, February 28, 2018. Accessed April 4, 2018. ↵

42 comments

Stephen Talik

Turkey treating this as a win for them and scrubbing it out of their history provides a good example of the saying that history is “written by the victors”. To this day there is still conflict between Greece and Turkey over the island of Cyprus, to the point that a United Nations peacekeeping mission has been there for decades and is still in place. Hopefully more treaties and conventions like the one in this article never come to pass.

Shriji Lalji

It is quite interesting to me how ones religion and traditions can result in such drastic actions. I never really understood why a group would want a complete homogeneous state. If everyone thought the same way there and believed the same thing culture would not advance. They would simply stay the same because there is no other perspective for improvement. I assume during that time many people were not able to fathom the idea of having several different religions and cultures living side by side in harmony.

Thomas Fraire

The prospect of going into war is specifically startling. I have never been the sort to hurt anyone however I comprehend that individuals who do battle need to carry out their responsibility. It disheartens me that wars never stop. I trust and petition God for world harmony one day. Notwithstanding, this article was imforamtive and I would peruse it once more on the off chance that I expected to.

Mariana Valadez

It is astounding how the countries had to divide and how it was caused by a collapse. It is interesting to read how each country developed in its own way. It is sad how people were forced out because of discrimination. Overall this article was very well written and interesting to read. It was very informative and I learned about the Ottoman Empire’s history.

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. It is really something that two governments can agree to uproot their peoples and force to move them. It is sad that this happened. I am sure that there were many turkish greeks and greek turkish people who did not want to leave, but really had no choice at all. 1.5 million people were uprooted and their whole lives changed that is just sad. I think that governments should work to bring unity to their people not by marginalizing minorities but by working to find common ground with the people who live within their borders

Hailey Stewart

It is so unfortunate that the Muslim community has faced such harsh discrimination throughout history. This article does a great job of making the reader really think about mass exile and cultural diffusion. Elements from the struggles of refugees are still around today. This article is extremely informative about the Ottoman Empire’s intricate history and organizes the dense information into social and economic effects.

Max Lerma

I had never heard of this massive exchange nor of this treaty. I think the way you were able to break down the numbers as far how many people owned what kind of property and technology is fascinating. It is interesting to see the effect that this large movement of people had on the nations’ economies and ability to further develop. I am glad that ultimately some of the people forced to move were able to go home.

Samire Adam

Through this article, I learned that this was the first time in history where people were forced immigration had occurred. I enjoyed reading this well-organized article. it was very informative.

Christopher King

As an empire collapses and if formed into a number of smaller countries, they are having to rediscover who they are and what they stand for. The Ottoman Empire had done just that when it collapsed. Unfortunately some of these new countries feel the need to make their country all about a race or religion and forces people such as the Greeks or the Muslims to move and make a new life. The repercussions are still viewed today. This article does a great job informing the reader.

Anais Del Rio

One thing that still amazes me to this day was that the Ottoman Empire was still around until mid-1900’s or so and is not something of the far past. It was sad that people who identified as one thing their entire life were forced to move to somewhere else based on their appearance or background. Of course with a large scale of moving there was bound to be bigger issues either economically or socially.