The battle at Valley Forge! Now when you hear this, I bet you’re thinking of combat, musket-balls, and even bloodshed. But this was not your typical man vs. man battle. This was more of a battle about survival against extreme conditions. Let me tell you a story about George Washington and his troops, and the unfortunate circumstances that they endured. It start with the continental Army breaking camp at White Marsh on December 11, 1777 and crossing a raft bridge spanning the Schuylkill river the next night. In an odd counterpoint to the maxim that history is written by the victors, even the most meticulous scholars and researchers have never been able to establish exactly how many soldiers George Washington led from Whitemarsh in late 1777. The consensus puts the total at somewhere between 11,000 and 14,000. As it was, all of these troops and most of their officers had no idea as to their destination.1 Washington had decided on encampment at Valley Forge, and so off they went. After all, it was only a day’s march from the city. There, he and his troops could train and recoup from the year’s battles. It was one of the reasons the commander chose it. Washington and the Continental army were going to have a harsh winter in the year of 1778. They would have to deal with lack of food, poor hygiene, and lack of both clothing and medicines. This was the kind of battle that the troops had to face that winter. How many would lose in this battle? This particular event lasted about six months. As the Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, you want your troops to succeed. But that was the challenge for Washington and his troops. This is a tale about the darkest hour of the Revolutionary war.

Here’s a little insight about the men who joined Washington’s army. The Continental Army was made up of disparate colonial militias, supported by hundreds of camp followers and allies. They emerged under Washington’s leadership as a cohesive and defensive fighting force. Forge Valley, the place of their encampment, was a naturally defensible plateau. The impassable roads and limited supplies stopped the fighting.2 Since the British were occupying Philadelphia, Washington decided on this spot. Little did he know that this spot would forever go down in history. On a more personal note, he argued that by not fulfilling his promises to adequately feed and clothe his soldiers, Congress had tarnished his good name and reputation. You can see his frustrations. Prior to this, General William Howe, the Commander of British forces in America, made his move on Philadelphia in September of 1777, thinking that, perhaps, the capture of the rebel capital would end the war. Now fast forward to early December. Washington began to think about a way to capitalize on the over extension of the British forces. His plan was to attack the outpost at Trenton. Howe loaded 15,000 troops on an Armada of ships and sailed from New York to Elkton, Maryland, on the Chesapeake bay. His forces then marched north on Philadelphia. Washington’s motives were to block Howe along the banks of the Brandywine River, but his troops were outnumbered and out maneuvered. He also attempted a bold surprise attack on the main British forces in Germantown earlier in October, but his plan was too complex. After his initial surprise attack and much confused fighting, the Americans were forced to retreat. For several weeks, the American forces camped out about twenty miles from Philadelphia. Some higher ups urged Washington to attack the British in Philadelphia, but the Commander in Chief realized it would be suicidal. His men were already shoeless and their uniforms in tatters.

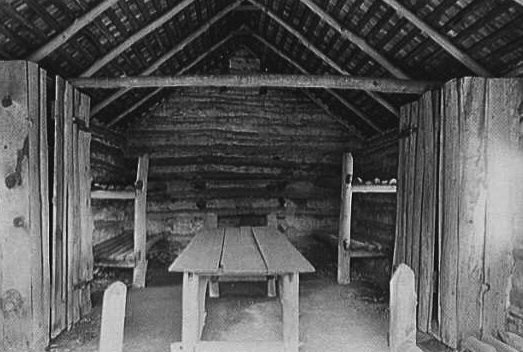

On December 12, the troops began to move from White Marsh to the west bank of the Schuylkill River at Valley Forge. It was a thirteen mile march that was delayed and took eight days. And to make matters worse, everyone had to endure the cold icy rain. Even traveling the sleet-filled roads was dangerous and even fatal. Finally, on December 18, the soaked and miserable troops marched into Valley Forge. Cold and worn out, the soldiers thought the worst was over, but they were wrong. They arrived on time for Christmas, but there was no holiday feast. This was upsetting. They already had been going along with little to no food. It was freezing, and they had no warm clothes, and many were even shoeless. And now they couldn’t enjoy a decent meal for the holidays? There was talk among the men; they spoke bitterly of “fire cakes and cold water.” By the end of December, Washington had no way to feed his men. “Unless some great and capital change takes place,” he wrote, his army of approximately twelve thousand men “must inevitably be reduced to one or other of these three things: starve, dissolve, or disperse.”3 While this was going on, Washington still continued to write letters to Congress, hoping for aid for his troops. The Commander’s first priority for the soldiers was to keep them warm and dry. There had been thirteen days of rain and snow during the first six weeks. “Starve, dissolve, or disperse,” were the words of Washington. Next was the building of wooden huts. Washington spelled out the style and the size of the headquarters. Every twelve men would share a 16×14 foot log hut, with walls six and a half feet high. Each hut would have a stone fireplace.4 Most huts were built in a pit, about two feet below the ground. Generally there was a dirt floor and some kind of cloth covering the doorway. Mind you, these huts were damp, smokey, and terribly unhealthy. Illness such as dysentery (infection in the intestines) and typhus (infectious disease caused by head-lice and fleas) were rampant and were the major killers of many of the men in this troop.

Sickness ran rampant because of the lack of transportation. The lack of transportation also caused supplies to be unavailable. Along with rutted roads, it was difficult to find waggoneers who were willing to transport items needed. Continental currency lost its value. Wouldn’t you want to point the finger at someone for all this madness? Finally, Washington blamed Thomas Mifflin, the Quartermaster General, for the fact that his army was poorly clothed, barely fed, and shivering in the cold of Valley Forge.5 Quartermaster General Mifflin despised his job of being head of transportation. His abandonment of his duties was a major contribution to the sickness and unhealthy conditions that surrounded the troops. It was an extremely unsanitary environment combined with poor personal hygiene along with the threat of an infectious disease called small pox (infectious caused by the variola virus). The exact number of people affected by these illnesses along with the exact number of deaths remains unknown. The medical department informed Washington that 1000 men were too ill to participate in combat and it was estimated that 3000 died from these illnesses.

In his mind, every predicament facing his army at this moment—from the lack of food and clothing for his men to the absence of fodder for their horses—could be laid directly at the doorsteps of the country’s local and national assemblies. There was almost nothing he could do to supply his army, short of scouring the countryside and robbing the very people his soldiers were called to defend. Before he did that, he would try again to wake the sensibilities of the nation’s politicians to the plight of the men who were defending the Revolution that put them in power.6 Washington constantly complained of the failure to clear encampment filth. This included rotting horse carcasses, and not surprising at all, the soldiers themselves were contributing to this disgusting setting. They were relieving themselves wherever they felt. The Commander in Chief even issued orders concerning the use and care of privies (a toilet located in a shed or hut outside). But the men continued to relieve themselves anywhere and everywhere. They would even use the restroom in the stream from where they drank. Intolerable smells finally prompted Washington to issue orders to soldiers that those who relieved themselves “just anywhere” rather than in “a proper necessary place” were to receive five lashes. Talk about rough, I mean think about it! These men had hardly any clothing or shoes, living in a literal cesspool. Eventually thousands of men had to battle these conditions, but sadly a lot suffered and died.

Understandably, this upset and discouraged Washington to the point that he actually sent concerned letters to Congress about the entire ordeal. George Washington’s “starve, dissolve or disperse” letter left American civilian authorities with little choice. Valley Forge was demographically, militarily, and politically an important crossroads in the Revolutionary War. It wasn’t until the spring when Washington’s most capable General, Nathaniel Greene, took over the Quartermaster post, and magically, food and supplies began to trickle in. With Greene in charge of supplying the army throughout the late winter and into the early spring of 1778, conditions finally improved for the soldiers.7 Despite the difficulties, there were a number of significant accomplishments and events during the encampment. One of those achievements was the maturation of the Continental Army.

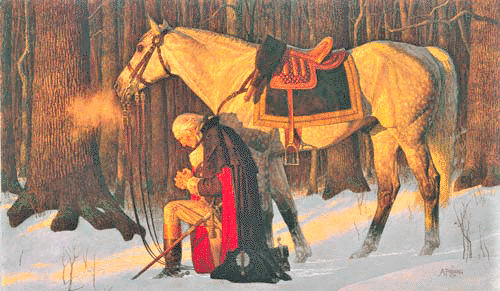

As hard as historians have tried to find the key that will unlock the mystery at Valley Forge, it is best to remember that history, like life, rarely has one explanation. Just as we are aware that many factors are shaping our lives today, some that we know and others that are hidden from view, so the men who marched with their commander to Valley Forge in December of 1777 understood some things clearly and others not at all. The same can be said of George Washington. As the soldiers of the Continental Army hurried through the bitter wind and falling snow to their winter camp at Valley Forge, they would have known several things for certain. Above all else, their cause was just. Despite many defeats on the battlefield, they were becoming an even better army. Finally, if they survived long enough, they would take up the fight against the British in the spring. But they would also have known that neither they nor their General would predict how their story would end.8 Perhaps no miracle shown greater than the endurance of the soldiers of the Continental Army and their beloved commander at Valley Forge. Images of hungry men shivering in the snow and their stalwart leader praying for them filtered into popular histories and school text books. Valley Forge was significant, not only for the reshaping of Washington’s army, but for the dedication, endurance, and resilience demonstrated by the Americans in their cause for independence.

I would like to thank the Dr Bradford Whitener for assisting me throughout this project. I am grateful for his advice and feedback in the various steps that this project went through to become published. I’d also like to express my gratitude to my family for allowing me to spend a lot of time and late nights on this project. They were all there to support me. I am so grateful to have had this wonderful opportunity to grow as a writer and to go above and beyond my expectations in order to achieve my goals.

- Bob Drury and Tom Clavin, Valley Forge (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), Chapter 11. ↵

- But the march was most miserable for the long roster of sick and wounded. ↵

- Nathaniel Philbrick, Valiant Ambition : George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution (New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books, 2016), 188. ↵

- Nathaniel Philbrick, Valiant Ambition : George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution (New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books, 2016), 187. ↵

- Mary Stockwell, “Washington at Valley Forge,” in A Companion to George Washington (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012), 216. ↵

- Mary Stockwell, “Washington at Valley Forge,” in A Companion to George Washington (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012), 214. ↵

- Mary Stockwell, “Washington at Valley Forge,” in A Companion to George Washington (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012), 211. ↵

- Mary Stockwell, “Washington at Valley Forge,” in A Companion to George Washington (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012), 211. ↵

11 comments

Michaell Alonzo

Hey Vanessa, congrats on being nominated for an article award. This post was so beautifully written and fascinating to read. This page has an astonishing quantity of specific information. I didn’t really pay much attention to the conflict of Valley Forge, but after reading this article, I can see why it’s such a crucial conflict. I also recognize how crucial the weather was. I really adored the pictures you chose, which perfectly complemented the narrative you were presenting. I really appreciated how well-organized you were; it made the reading interesting for me.

Guadalupe Altamira

First and foremost congratulation on your nomination and wish you the best of luck on award day. I was very aware of Valley forge but I was not aware that it was a choice to go there. I thought it was a need to go there but it seems that was not the case. This article was very informative and told very clearly. I also liked the tone used in the article

Joshua Marroquin

Despite being initially praised by the Spanish Crown, Cortés soon found himself outnumbered by a new generation of colonial administrators and engaged in ongoing legal disputes where he was accused of abusing his power, taking more loot than was due, and committing atrocities against indigenous peoples. This was just a bit of knowledge I gained from reading this article.

Brandon Vasquez

First off congratulations on your nomination! In high school and college, we learn about the battles of the Revolutionary War as well as the colonist’s fight for independence but we never get to spend a lot of time on what really goes on when an army is encamped especially like the continental army was at Valley Forge. You did a great job explaining the difficulties the army faced and it allowed for me to understand a lot more about what was really going on while the army was encamped.

Helena Griffith

Thank you for the nomination! Although I’ve always known a little about Valley Forge, I was unaware that George Washington had made a deliberate decision to visit it. And that he was aware that there would be no route for bringing in supplies. It is astonishing that males were simply adding to the squalor without realizing how their actions affected health inequalities.

Ana Barrientos

I have heard of Valley Forge before and how George Washington and his troops struggled during that time, but I didn’t know the details of it, and I think you did a great job explaining it. I also love the images you provided especially the hut because it gave me more of an idea as to what they were living in. Another thing, I enjoyed how enthusiastic you were telling this story! Awesome job and congratulations on your nomination!

Rafael Portillo

Congrulations on your nomination. I was really impressed on the way you made the story come to life. I knew Washington dealt with a lot of hardships during battle but your article really made me see a new perspective. Life happens and we have to learn and adapt. That is something I gathered while reading your article. Thank you.

Dylan Vargas

The Battle of Valley Forge was a topic that I didn’t really pay attention to much. But after reading this article, I can see why it’s such an important battle. Not because of the people involved but the weather that was involved. I knew it was important to history in its own way but I didn’t know it was because of the harsh weather that devastated the men in battle.

Courtney Mcclellan

Congratulations on your nomination! I have always known a little about valley forge but i had never known that George Washington had made an explicit choice to go there. And that he knew that there was going to be no way to get any supplies into the area. The fact that men were just contributing to the filth and not understanding how they were contributing to the health disparities is astounding.

Theresa Muller

This was an excellent article to read as it was very informative and held my attention well! I remember briefly learning about Valley Forge in high school but definitely not to this extent. This article has truly broadened my knowledge on the subject. I can see the passion you have for this topic through the article, well done!

Vanessa Preciado

Thank you sooo much! I appreciate your feedback:)