California, like other states, experienced growth spurts during the 1930s and through the 1940s. Los Angeles saw significant growth as Hollywood became the focal point of producing motion pictures and of becoming the home of movie stars. California was a popular place for Mexicans to migrate to, in search of a better life than they had living in Mexico. They were also competing for jobs against Mexican Americans and other minority groups. There was enough work for immigrants until the Great Depression hit. Then, it was expected that all jobs would be given to the “white Angelenos.” The availability of jobs and housing was further reduced when the Dust Bowl occurred, and white people started migrating from the Midwest to California. Tensions were rising because many white Angelenos wanted stable access to employment. They felt that their city, Los Angeles, and their jobs were being taken over by immigrants and non-Angelenos.1

As the population of Los Angeles grew, Mexicans and Mexican Americans were being pushed into barrios, neighborhoods that were made up solely of Mexicans and Mexican Americans. These barrios were a place of refuge for many immigrating Mexicans. Here they could find work and create a community with each other. These barrios frequently received new individuals and families as they arrived in Los Angeles, settling anywhere they could find space to live. Living conditions could range from life in a basement, to an alley, to shanties, or even to debilitated homes with rooms to spare. However, any housing that Mexicans could get in California was better than the life they had in Mexico.2

There was some relief provided to Mexicans when the United States became involved in World War II, with the creation of the Bracero program, also known as the Emergency Labor program, in December 1941. The Bracero program opened jobs in factories and agriculture to Mexicans as white Angelenos were called to serve in the war. The Bracero program was a unified effort between the United States and Mexico to give decent paying jobs to Mexicans and an opportunity to live the American life. However, in practice, that wasn’t the case, as Mexicans were subjected to low pay and horrible working conditions. Mexican workers could not make complaints about pay and working conditions for fear of being sent back to Mexico. If they did complain, their concerns went unheard as they were under the control of white Americans.3

As the spirit of nationalism and “Americanism” was increasing, Mexicans and Mexican Americans were looked down upon by their white Angeleno counterparts. White Americans continued to feel they were being pushed out of their city by the increasing number of immigrants coming in. They inferred that these immigrants were the cause of increasing crime and poverty rates in the city, and that they were involved in gang activity. Mexicans and Mexican Americans got a “break” when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. After Pearl Harbor was attacked, xenophobic attention was now targeted at Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans living in the United States. Now the Japanese were considered the enemy. As a result of President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, Japanese immigrants, Japanese Americans, and anyone else who they deemed to be a threat to national security were placed in internment camps.4 Although white Californians focused their wrath on the Japanese after Pearl Harbor, the impetus to purify their cities and towns from the enemy’s presence spilled over to other groups deemed equally subversive of cherished American customs.5

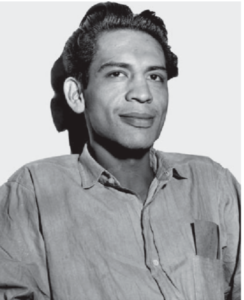

August 1, 1942 is the date when everything started going steeply downhill for Mexicans and Mexican Americans in Los Angeles. That night, there was a birthday party being held on Williams Ranch that was hosted by a family that lived there. Near the ranch was a watering hole called Sleepy Lagoon where Henry Leyva and his friends from the 38th Street neighborhood were hanging out. A group of young men came upon Leyva and his friends at Sleepy Lagoon and beat them up while yelling insults at them. Leyva and his friends made it back to their neighborhood on 38th Street and recruited friends to go back out to Sleepy Lagoon to seek revenge. When Leyva and his group arrived, the young men that had attacked them were no longer there. Someone suggested that they might be at the birthday party on Williams Ranch. Leyva and his friends entered the house where the birthday party was being held and demanded to know where the attackers were. The party hosts and guests were confused about what was going on and demanded that Leyva and his crowd of friends leave the party. That is when a fight broke out involving everyone. The fight only ended when someone shouted that the police were coming. Leyva and his friends jumped in their cars and left back to their 38th Street neighborhood. When the police arrived, they found Jose Diaz, a birthday party attendee, unconscious and lying on the ground. Diaz was found with a bruised and bloody face along with stab wounds. After 45 minutes, Diaz arrived at Los Angeles General Hospital, where he was diagnosed with a severe cerebral concussion. He died an hour and a half after his arrival.6

At any other time, the death of Jose Diaz would have gone unnoticed in Los Angeles. However, Diaz’s death came at a time when Los Angeles law enforcement and California state officials wanted to start lowering crime statistics amongst gang-affiliated minorities. This automatically put the Jose Diaz death into the spotlight as Latinos were involved in the violence. The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) went out and interrogated over 600 Latino men and women – the majority of whom wore zoot suits. Zoot suits consisted of a long coat with wide shoulders and lapels along with high-waisted pants that hung around the knees, narrowing down to a tight fit around the ankles. Zoot suiters would wear thick-soled shoes, broad-brimmed hats, suspenders with narrow belts, long watch chains that hung from either a vest or pant pockets, and their long hair was combed back in what was called an “Argentinian” style. This trend became popular with young Latinos and some African Americans as a way of showing rebellion against the traditional clothing of older generations.7

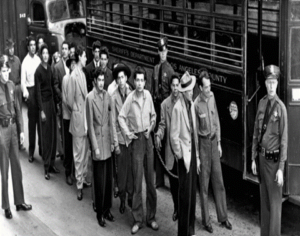

After several months, Leyva and about thirty other individuals (all zoot-suit wearing Latinos) were considered suspects in the death of Diaz and were eventually put on trial for murder. LAPD argued that this trial would show Mexican Americans that Los Angeles would not put up with their criminal and delinquent behavior. The case became officially known as California vs. Zammora, and the suspects were identified as the 38th Street gang (even though they only belonged to the same neighborhood, not a gang). The trial against the final twenty-two suspects lasted from October 1942 until January 1943, and, for the first time ever in California, all defendants were tried at the same time. The trial was heavily publicized by the local newspapers. They published demeaning headlines each day about the suspects. This further incited the hatred of white Angelenos toward zoot suits and Mexican Americans. Newspapers referred to the suspects as gang members, vagabonds, and other discriminatory terms. The trial was beginning to shift away from focusing on the death of Jose Diaz. Rather, its goal was to be a lesson for Mexican Americans to “fix” their behavior and not act as threats to society. At the sentencing of the trial, all twenty-two young men were found guilty. In total, three were found guilty of first-degree murder, nine were convicted of second-degree murder, five were found guilty of assault, and five other defendants received separate trials, eventually being acquitted.8

Hostility between Mexican-American zoot suiters and military personnel were at an all-time high after the Sleepy Lagoon trail. Mexican-American zoot suiters and military members were often involved in brawls where each group was said to be protecting the honor of their women. Tensions began when drunk servicemen would berate and harass young Mexican-American women. Young Mexican-American men felt that they had to defend the honor of their women and protect them from the drunk military men. Newspapers only added to the hatred against zoot suits as they published headlines condemning the wearing of zoot suits and called anyone who wore zoot suits “gangsters.” Another factor was that servicemen saw zoot suiters as “draft dodgers” and unpatriotic. During this time, from 1942 to 1943, America, still in the fight against Japan, faced rationing to ensure that military members would have the supplies needed to fight the war. Fabric and wool were on the list of rationed items. In production, zoot suits required much more of these materials than other American fashions. Seeing zoot suiters angered servicemen who were on leave in Los Angeles, and it often led to verbal and physical assaults.9

The reason there were so many military members at this time in southern California was due to the many military bases that were located there. These military bases served two main purposes during World War II: to train new servicemen and to protect and defend America against another possible attack from Japan. In addition to training new military members, Southern California and Los Angeles grew as well with factories and manufacturing to support the war effort. Servicemen would frequent Los Angeles and San Diego on their off time from training and on the weekends.10

Tensions were rising as fights kept occurring between both groups until May 31, 1943, when a Navy military member, Seaman Second Class Joe Dacy Coleman, thought a zoot suiter was going to attack him, and this incident led to the start of the zoot suit riots. Coleman and about ten other sailors were walking down a Los Angeles street when they came upon some Mexican-American females. Some sailors stopped to talk to the young women, as Coleman and another sailor continued walking. Coleman and the other sailor passed a group of a dozen zoot suiter Latinos, and Coleman thought he saw a zoot suiter raise his hand to attack him. Instead, Coleman reacted first by grabbing the zoot suiter he thought was going to hit him by his arm at the same time Coleman was struck from behind on his head.11 Coleman continued to be attacked by zoot suiters until other military members were able to rescue him and get him to safety. When the sailors returned to their base, other military personnel observed the battered state Coleman was in and vowed to take revenge on Mexican Americans – whether they wore zoot suits or not.12

On June 3, 1943, American service members went into Los Angeles to look for zoot suiters to seek vengeance for what happened to Coleman. Military personnel were not having any luck finding zoot suiters on the streets of Los Angeles, so they decided to go into a movie theater to find them. There, they found innocent twelve- and thirteen-year-olds, who were wearing zoot suits watching a movie. The service members beat up the juveniles, tore off their zoot suits, and burned their clothes as the naked young boys watched. After that, the servicemen went into any bar, restaurant, and theater nearby looking for Mexican Americans wearing zoot suits to harass.13

As the weekend of June 5 and 6 came near, service members from several branches (Army, Navy, and Marines) frantically rushed to get their weekend passes to go off base in their search of zoot suiters. Even though the military leaders were aware of the tension between their military members and zoot suiters, they still issued everyone a weekend pass. As the servicemen made their way to downtown Los Angeles, they picked up anything along the way, such as broom sticks, rocks, belts, and dumbbells, to use as weapons. When the active duty men were done going through downtown Los Angeles beating Latinos, ripping the clothes off anyone wearing a zoot suit, and burning the hated clothes, they made their way into nearby Los Angeles neighborhoods looking for more Mexican Americans. They even extended their beatings to African Americans.14

Courtesy of Library of Congress

LAPD did little to calm the riots or discipline the service members. Instead, the LAPD arrested the zoot suiters who had been beaten up and put them in jail. The LAPD believed that the service members were helping them with the Mexican American gang problem that Los Angeles was facing. On the nights of June 6 and 7, the last nights of the riots, the violence worsened. Mobs of servicemen, up to 5,000, descended into Los Angeles to help with the riots.15 In addition to the military members, white Angelenos also joined in the riots, beating any Mexican American and/or African American they could find in downtown Los Angeles and its adjacent neighborhoods.16

The zoot suit riots officially ended on the morning of June 8, 1943, when senior military leaders declared Los Angeles off limits to all military personnel. At the same time, the Los Angeles city council created an ordinance that made wearing zoot suits illegal on any Los Angeles streets. If anyone was caught wearing a zoot suit, they would be arrested and jailed for fifty days. In the end, there were ninety-four civilians and eighteen servicemen that were treated for serious injuries during the riots. The LAPD arrested all ninety-four civilians and only two servicemen.17

In the end, all parties put the blame on each other. Military leaders tried to convince the public that their service members were using self-defense and protecting their wives and families from the zoot suit gangs. Military leaders also put the blame on LAPD for not doing anything to stop the riots when they were occurring. The military claimed that they had no control over the white Angelenos that were participating in the riots.18

LAPD blamed military leaders for not keeping the servicemen confined to base during the riots since they were aware of what was going on in Los Angeles.19 Newspapers were also to blame for their negative articles towards Mexican Americans because they published front page articles claiming zoot suiters were to blame for juvenile delinquency and crime activity. Eleanor Roosevelt even made a statement about the zoot suit riots in which she called them a racial riot. Her comment upset many white Angelenos because they didn’t see it as a racial riot, but servicemen who were helping out with social unjust.20

A commission was formed to investigate the zoot suit riots, and it scolded the white Angelenos and across California for their overreaction to the zoot suit fashion trend. The zoot suit riots were in fact a race riot and it took the investigation to reveal that. The riots took place in the Mexican American neighborhoods and specifically targeted zoot suiters. A statement was made that if this had occurred in Beverly Hills, it would have had an entirely different outcome. “The wearers of zoot suits are not necessarily persons of Mexican descent, criminals or juveniles. Many young people today wear zoot suits. It is a mistake in fact and an aggravating practice to link the phrase “zoot suits” with the report of a crime.”21

- Eduardo Obregón Pagán, Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2004), 29-37. ↵

- John J. Chiodo, “The Zoot Suit Riots: Exploring Social Issues in American History,” Social Studies 104 (1), 2013), 1–14. ↵

- Kevin Hillstrom, “A City on Edge” The Zoot Suit Riots (Omnigraphics, 2013), 35-38. ↵

- National Archives, 1942, “Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration.” ↵

- Eduardo Obregón Pagán, Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2004), 46-47. ↵

- Kevin Hillstrom, “A City on Edge.” The Zoot Suit Riots (Omnigraphics, 2013), 38. ↵

- John J. Chiodo, “The Zoot Suit Riots: Exploring Social Issues in American History,” Social Studies 104 (1), (2013): 1–14. ↵

- Anonymous, Public Broadcasting Service. Zoot Suit Riots. ↵

- Eduardo Obregón Pagán, Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2004), 115-118. ↵

- Seth Abramovitch, “Zoot Suit Riots Rocked L.A. in the Summer of ’43,” Hollywood Reporter (website), 2021), https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/local-news/zoot-suit-riots-rocked-l-a-in-the-summer-of-43-1234961084/. ↵

- Seth Abramovitch, “Zoot Suit Riots Rocked L.A. in the Summer of ’43,”Hollywood Reporter (website), 2021), https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/local-news/zoot-suit-riots-rocked-l-a-in-the-summer-of-43-1234961084/. ↵

- Kevin Hillstrom, “A City on Edge” The Zoot Suit Riots (Omnigraphics, 2013), 78-80. ↵

- Seth Abramovitch, “Zoot Suit Riots Rocked L.A. in the Summer of ’43,” Hollywood Reporter (website), 2021), https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/local-news/zoot-suit-riots-rocked-l-a-in-the-summer-of-43-1234961084/. ↵

- Richard Griswold del Castillo, “The Los Angeles ‘Zoot Suit Riots’ Revisited: Mexican and Latin American Perspectives,” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 16, no. 2 (2000): 387–391. ↵

- “Los Angeles Barred to Sailors by Navy to Stem Zoot-Suit Riots: Army and Civilian Authorities Join in Measures to Halt Outbreaks and all Patrols are Strengthened.” 1943. New York Times (1923-), Jun 09, 23. ↵

- Eduardo Obregón Pagán, Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2004), 134-136. ↵

- “Los Angeles Barred to Sailors by Navy to Stem Zoot-Suit Riots: Army and Civilian Authorities Join in Measures to Halt Outbreaks and all Patrols are Strengthened,” 1943, New York Times (1923-), Jun 09, 23. ↵

- Kevin Hillstrom, “A City on Edge” The Zoot Suit Riots (Omnigraphics, 2013), 84-89. ↵

- Carey McWilliams, “The Zoot-Suit Riots, 1943,” in The Immigrant Experience, American Journey (Woodbridge, CT: Primary Source Media, 1999) (accessed April 17, 2023). ↵

- Eduardo Obregón Pagán, Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2004), 151-153. ↵

- Quoted in “Los Angeles Group Insists Riots Halt,” New York Times, June 13, 1943. ↵

3 comments

Gaitan Martinez

I’ve previously read about the suit zoot riots and it’s a tragic event that I’m extremely happy to see this get covered. I Read about this event while taking a mexican-american studies class. Another tragic event that shocked me was when Herbert Hoover got over 1 million Mexican-Americans deported because they “were stealing jobs.” Another fact I would like to earn was that Adolf Hitler got the idea of gas chambers from the US gasing Mexicans when caught entering the US to make sure they didn’t have any diseases.

Christian Lopez

As a Mexican American myself I feel like while our troubled history is explained at times we are still heavily left out in a majority of history. Seeing well written article such as this reminds me of the struggles that our ancestors faced and how much me have grown as a community and as a people.

Christian Lopez

Maggie, thank you for bringing to light some of the struggles that the Hispanic community, specifically the Mexican American community has faced over the last several deacedes.