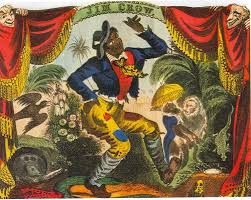

In the theaters of the Byzantine empire’s capital city, Constantinople (current-day Istanbul, Turkey), actors and actresses were seen as bottom feeders of society, disrespected and jeered by their audiences. One of the streets in Constantinople’s theater district was known as “Harlots’ Row,” painting actresses as essentially glorified prostitutes.1 Unfortunately, it was true that obscenity sold; actresses who chose to perform ‘less than refined’ acts would gain more fame and reception from the audience. An actress known for that was Theodora, who later became one of the most influential empresses in the Byzantine Empire.

Before that, Theodora had to continue her life in the theaters. Her rise to notoriety began with her almost naked performance of “Leda and the Swan.”2 She sold herself to the spotlight, in her effort to gain the favor of her male audience and hold a semblance of power over them. Eventually, she grew tired of subjecting herself to the exploitative entertainment industry, and followed her lover, Hecebolus, to Africa. Hecebolus was appointed to a new post as the governor of the Libyan Pentapolis.3 To Theodora, this was a way out of her unkind life, so she took the chance. Unfortunately, she and Hecebolus could never fully be happy with one another, leading Hecebolus to discard Theodora.4

All alone, Theodora traveled to Alexandria, Egypt, and had her own spiritual awakening. Her encounter with religion was significant enough to cause her to return to her hometown of Constantinople and take up the livelihood of spinning wool. In her return to Constantinople, she met Justinian, nephew of the current Byzantine emperor Justin and heir apparent to the Byzantine throne, and the rest is quite literally history.5

Justinian was completely enamored with Theodora, and they began to live together in the Palace of Hormisdas. The lovebirds had not yet moved into the Imperial Palace because of Empress Euphemia’s disapproval. However, keen on his nephew, Emperor Justin bestowed the patrician status upon Theodora, a status only given to a woman after her husband had it. Theodora had attained the status of a wife even without the necessity of marriage and was said ‘wife’ to the next Byzantine emperor. She had become a woman of significant influence and had truly rid herself of the less-than-kind reputation from her earlier years.6 However, Theodora and Justinian’s commemoration of their love ran into some issues. According to the law passed by Constantine the Great, marriage between senators — Justinian’s class — and actresses or daughters of actresses, was strictly forbidden.7 Empress Euphemia greatly encouraged the law and Justin listened to his wife. After her death though, Emperor Justin became much more malleable and was convinced by both Justinian and Theodora to modify “the legal barrier” standing in the way of their marriage.8 Theodora and Justinian were wedded in 525. While waiting for Justinian’s assumption of the throne, Theodora “learned court etiquette, observed and discerned the centers of political power, and formed alliances with key palace players” in preparation for her incoming role.9 Thus, Theodora not only looked the part of empress with her famed beauty, but also acted the part of the most powerful woman in the empire. Around two years after their marriage, the couple assumed the throne and their reign began. Theodora had done it; she rose from the impoverished and disrespected ranks of her actress life and became the woman everyone in the empire admired, wanted, and respected.

Upon the acquisition of her new power, Theodora thoroughly enjoyed the luxuries promised to those of imperial status. She “slept late and took long, voluptuous baths before breakfast, for warm baths were considered good for the health.”10 She ate gourmet meals, received plentiful gifts from her husband, and took solace in the many imperial estates. She finally had the privilege she had so desperately craved during her time as an actress. Recognizing that, she used her power to implement legislation that would offer a better life to the countless actresses and prostitutes within the empire.

Specifically, Theodora had a steadfast determination to eliminate prostitution from the empire’s capital. With Justinian’s help, she “ordered the brothels closed in 528 and their keepers..rounded up.”11 To ensure the women’s freedom, she “[refunded] the purchase price to their masters” as well as giving the women clothes and funds to lead lives free from poverty.12 All these actions were part of an “imperial program to cleanse the city of vice.”13 With it, Theodora also influenced laws that released prostitutes from staying in the profession and freed actresses from being forced to stay in the theater. Theodora solidified her role as a trailblazer for women’s rights in the Byzantine Empire with her actions to better the lives of actresses and prostitutes. Essentially, she became the hero her younger self deserved.

Through Theodora and Justinian’s goals of bettering the empire for all, higher taxes were raised against the subjects in order to finance their many projects. The tension created from the taxes eventually led to a climax in 532 where the circus factions — Blues and Greens — united against the empire, which became known as the Nika Riots. The rioters crowned a new emperor and Justinian prepared to flee for his life.14 However, Theodora instead chose to stand her ground and refused to flee. She spoke to the empire’s council and Justinian and convinced them that it was more noble to die with their nobility than flee as a cowardly exile. With Theodora’s guidance, Justinian ordered the riots to be suppressed, causing a severe massacre but securing their reign in history.15 Theodora’s role in the Nika riots solidified her power and role not only as a wife but as a ruler in her own right. She and Justinian also used the riots as an opportunity to rebuild the city, contributing to their legacy with their redesign of the still-standing Hagia Sophia.16

After the Nika riots, Theodora continued with her role in the governance, such as her influence in the passing of laws that promised inheritance rights to women. She established shelters of sorts for the women who had been victims of abuse and trafficking.17 Overall, she improved the status of all women in the empire.

In her later years, she began to struggle with a disease akin to breast cancer. Despite this obstacle, she stayed politically active to guarantee her reforms would outlive her. She passed in June 548 CE, but her influence on Justinian and the empire persisted.18 Justinian, greatly affected by her passing, continued several of her policies and reforms.

Though her power only came to her through her marriage, Theodora used every ounce of it to better the status of women, especially those in the entertainment world, in the Byzantine Empire. Having experienced firsthand the hellish reality of being a woman in medieval times, she fought tirelessly for women—whether related to her or not— to gain the rights they deserved. In the time period of her, she was the prime example of a woman exemplifying her capability to induce social and political change in a male-dominated society. She was well ahead of her time, essentially being the first brick laid in the foundation for the countless feminist movements to come after. That is why Theodora was not only the wife of the great Justinian and an admired Byzantine empress, but also, ultimately, a medieval-time feminist.

- James Allan Evans, The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian (Austin, United States: University of Texas Press, 2002), 14. ↵

- James Allan Evans, The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian (Austin, United States: University of Texas Press, 2002), 15. ↵

- James Allan Evans, The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian (Austin, United States: University of Texas Press, 2002), 16. ↵

- Gloria Fulton, “Theodora,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022). ↵

- James Allan Evans, The Power Game in Byzantium : Antonina and the Empress Theodora, 2011, 37; Gloria Fulton, “Theodora,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022). ↵

- Gloria Fulton, “Theodora,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022); James Allan Evans, The Power Game in Byzantium : Antonina and the Empress Theodora, 2011, 48. ↵

- James Allan Evans, The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian (Austin, United States: University of Texas Press, 2002), 19. ↵

- James Allan Evans, The Power Game in Byzantium : Antonina and the Empress Theodora, 2011, 49. ↵

- Gloria Fulton, “Theodora,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022). ↵

- James Allan Evans, The Power Game in Byzantium : Antonina and the Empress Theodora, 2011, 52. ↵

- Clive Foss, “The Empress Theodora,” Byzantion 72, no. 1 (January 1, 2002), 150. ↵

- Clive Foss, “The Empress Theodora,” Byzantion 72, no. 1 (January 1, 2002), 150. ↵

- Clive Foss, “The Empress Theodora,” Byzantion 72, no. 1 (January 1, 2002), 150. ↵

- Gloria Fulton, “Theodora,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022); James Allan Evans, The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian (Austin, United States: University of Texas Press, 2002). ↵

- James Allan Evans, “The ‘Nika’ Rebellion and The Empress Theodora,” Byzantion 54, no. 1 (January 1, 1984): 380–82. ↵

- Gloria Fulton, “Theodora,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022). ↵

- Gloria Fulton, “Theodora,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022); C. E. Mallet, “The Empress Theodora,” The English Historical Review 2, no. 5 (1887): 1–20. ↵

- Gloria Fulton, “Theodora,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, September 1, 2022) ↵

4 comments

arosales11

I hadn’t had any knowledge whatsoever of this feminist and this piece was absolutely perfect to learn about Theodora. Each point was well-structured, and the story flowed naturally. You made the information easy to understand by clearly presenting your facts and assertions. The subject of the study was intriguing and expertly handled. I’m excited to investigate Miss Torres’ work further in the future.

Natalia De la garza

This infographic is excellent! It vividly illustrates Empress Theodora’s remarkable journey from her early life as an actress in Constantinople’s theater district to becoming one of the most influential figures in Byzantine history.

Benicio Acuna

What a wonderful read! This was my first time engaging with research from St. Mary University, and I found this to be exceptional. Every point was thoughtfully organized, such a cohesive narrative. You presented your facts and statements in a clear manner that made the information easy to follow. The research topic was fascinating and very well-executed. I look forward to exploring more of Miss Torres’ work in the future.

Paulina

Congratulations Savannah! So proud!!