Throughout our school life, our history textbooks are filled with stories of great men and women. We find people who, either through diplomacy, skill, morals, or shear chance, managed to change the course of humanity, for better or worst. While knowledge of such important men and women is a good thing to have, it doesn’t give us the fullest understanding of the human condition. After all, according to a quote from Samuel Knapp, “If the proper study of mankind is man, every form of character should pass through our notice.”1 It just so happens that the character put forth in this article is one of the interesting ones, not because he was particularly skilled, or smart. Quite the opposite, in fact.

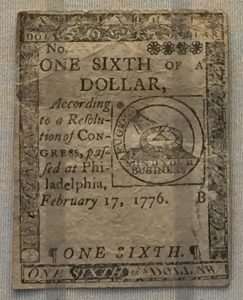

The story of this man begins in the town of Malden, Massachusetts, specifically in a house on Bradford Street. There, to Nathan and Esther Dexter, was born our protagonist, Timothy Dexter on January 22, 1747.2 He grew up to learn the leather dressing industry of his father. At the time of his apprenticeship, the secret of dressing leather in the “Moroccan style” became known to some, but not to all, dressers in the area. This gave Timothy Dexter a monopoly on the style, and at age twenty-one, he commenced his own business in the industry, moving to Newburyport in the process. In such industry, he was able to make a decent amount of wealth for himself, and he even married a well-off older woman, and gained even more money from it. But it was not enough to propel Timothy Dexter into the upper class on its own.3 His chance to rise into the American elite, however, came after the fires of the Revolutionary War died out. He was jokingly given the advice to buy up some Continental dollars by one of the Newburyport townsfolk. After all, other aristocrats were doing the same, buying up the worthless currency the soldiers were initially paid in as a sort of thanks for fighting and dying for the aristocrats’ freedom. Timothy Dexter took this advice in full stride, buying up large sums of Continental dollars. Such a venture, at a first glance, might appear to be fairly unwise, especially if given enough knowledge on the history of US currency. After all, there was a popular saying of the time, that if you wanted to say that something was worthless, you could say it “Wasn’t worth a continental.”4

To understand how this venture was irresponsible at best, and suicidal at worst, we should first know the history of the Continental dollar. During the American Revolution, the American government financed the war through the issuance of “Continental Dollars,” specifically from the years 1775 to 1779.5 Of course, the immediate issue with the currency was quite visible. The American Government, at that time, was not a government. It did not have the institutions necessary to distribute a reliable currency. Anyone who used the currency would be taking a gamble as at the time, the dream of an independent America was just that, a dream. If the rebellion failed, those who held the currency might be at risk for prosecution by the British government. Despite this, things started out alright in 1775, with the Continental Congress ordering the production of two million Continental dollars, which rested atop a $12 million estimated value of each colony’s individual paper money issuances prior to the war. With this, Congress figured it could finance the war. It couldn’t, not even until years end. In response, it printed another $4 million Continental dollars. The Continental dollar barely lasted a year before immediately dropping in value, thanks to the mass circulation of continental currency. The worst part is, Congress wasn’t done. In the famous year of 1776, not only was the Declaration of Independence signed, but Congress celebrated the occasion by printing another $19 million Continental dollars. The presses continued to print this currency over the next five years.6 To add to these financial woes, the British seized the opportunity to utilize the rebelling colonies’ currency against it. They took the Continental currency, studied it, and then mass produced it, using its subsequent inflation as a weapon of war. The British did this in a three-pronged attack. First, the British printed and circulated their version of the Continental dollars into the territories they occupied. Then, they sponsored the American colonists loyal to them, or the Tories, to do the same on their own. To top it all off, they utilize propaganda to reduce colonial faith in the currency. The British did this by simply pointing out the amount of high quality counterfeit currency there was in circulation. After all, why would anyone support a currency system that is failing? In short, while the British weren’t entirely responsible for the devaluing of Continental currency, they certainly contributed to its devaluing.7 In the end, how much of this glorified firewood was produced? Estimates vary, but according to the analysis of one economist, between the years 1775 and 1779, “a total of only $199,990,000 Continental Dollars were issued as Congressional spending.”8 In 1781, the Continental dollars were trashed, and a lot of them were burnt, hence the phrase, “Not worth a continental.” At that point, one could buy up of the worthless money for mere pennies.9

Needless to say, with how much Timothy Dexter spent on buying up this worthless currency, he should have faded into obscurity as a poor individual. However, Timothy Dexter’s luck kicked in the doors of misfortune and left no evidence that misfortune even existed. Dexter’s salvation came in 1790. Congress, with its recently ratified Constitution, wanted to get rid of any remaining Continental dollars still in circulation so as to prevent counterfeit. On the 4th of August, it passed the Funding Act of 1790, which valued these Continental dollars to be worth their face value of one dollar for every Continental dollar.10 That doesn’t sound like much, but keep in mind that Dexter had bought a lot of these dollars for mere pennies. The profit he made from this venture was around $10,000.11 According to the CPI inflation calendar, that amount from 1790 would be worth almost $300,000 today.12 Overnight, Timothy Dexter instantly became a member of the upper class of society.

Now that Dexter was part of this upper class, he wasted no time in fully indulging himself in all that his new life had to offer. First, he changed up where he lived, buying a mansion and transforming it. Aside from working on the actual foundation of the house by raising some minarets, he also painted the house to look like a court jester, using the colors red and yellow.13 Yet, Timothy was not done. He soon raised statues of some of history’s most influential individuals, including Napoleon Bonaparte, Alexander Hamilton, and, of course, himself, twice. On the statues of himself was a plaque that read “I am the first in the East, the first in the West, and the greatest philosopher in the world, Lord Timothy.”14

This “elegance” did not last. There was a reason Timothy Dexter’s wife was seldom home. The simple fact was, being inside the home made her uncomfortable. Timothy Dexter and his son would, with the aid of their companions, transform the house into what was essentially a brothel. Dexter would throw large parties in the best parts of the mansion, like the fictional character Jay Gatsby, but more intense. With time, the house’s furniture and wallpaper would stain and give off a disgusting odor, which probably made Mrs. Dexter stay home less and less. Timothy Dexter didn’t seem to mind, however, and would even furnish his house with a library. Naturally, Timothy Dexter didn’t read much. Rather, he wanted the library just so he could look intelligent and wealthy. Despite this, he managed to pick up some really valuable bound books, but he would also pick up some worthless books as well, storing “low-art” periodical publications with books of considerable literary merit. However, all the books, valuable and valueless, would share the fate as the rest of Timothy Dexter’s house, ending up defaced, bookmarked, and torn, to the point that when Timothy’s library was sold, it didn’t have much value. Timothy Dexter would also take an interest in horses and would buy a pair of cream-colored horses for his carriage. These, however, he would quickly replace with grey horses, once he lost interest in their color.15

The other aristocrats of the time didn’t like sharing their elite space with an arrogant, barely literate, and vulgar individual who came to wealth through luck. However, they did find him amusing. This amusement would inspire some merchants to jokingly suggest to Timothy Dexter that he “ship warming pans to the Caribbean.”16 Warming pans were tools used in the early-to-mid 1800s before electronic heating, as a way to keep beds in colder climates warm. The Caribbean is fairly known for being a very tropical climate. As such, the plan of shipping warming pans to the Caribbean is very much a fool’s errand. However, Timothy Dexter was not deterred by such conventional thinking, and as such, sent a large shipment of these warming devices to the Caribbean. Surprisingly enough, he made a profit on the venture, thanks to the primary output of the Caribbean: sugar. More specifically, molasses.

Molasses is one of the products that can be made from sugar cane. Sugarcane is not native to the Americas, nor even to Europe, but rather to Asia. It was introduced to Europe in 326 BCE by Alexander the Great during his invasion of India, when he first came across the sugar cane. Arab traders would later take this sugar cane and spread it across the Mediterranean, with Spain receiving it around 714 CE, eventually replacing honey as a primary sweetener. In Columbus’s second expedition to the Americas, in 1493, he brought sugarcane stem cuttings from the Canary Islands to Hispaniola. Eventually, other colonial powers would see the value of the tropical climate, and would begin to bring their own sugarcane to their own Caribbean colonies. The processing of sugar from sugar cane takes time and requires a lot of work and effort, but it can be extremely profitable. After all, once a sugarcane stem was planted and ripened, it would produce crops for three to six years before having to be replanted. In order to produce sugar from it, the cane would need to be cut when ripe and taken to a mill. The mills, specifically during the period Dexter pursued his warming pan related venture, used three vertical rollers. These would ground the cane, extracting the calorie-rich, syrup-like juice that was contained inside. This juice would then need to be cleaned through the use of lime, and then further purified through straining its impurities. The now pure juice would then be boiled in kettles until it crystalized into granular sugar. Molasses is also produced from this, and is the left-over syrup that can no longer be crystalized. Now, European colonies were doing this on a massive scale, and as such needed a lot of workers for the tiring work in the hot climate. These workers would also need to be monitored in order to make the most out of the crops. Unfortunately, there weren’t enough Europeans in the colonies willing to undertake this arduous task. So, colonies resorted to slave labor, specifically using Native Americans. The problem was, most of these natives would either escape into an area they knew well, and thus were able to hide successfully, or died of diseases brought over by the Europeans. In response, the Europeans turned to importing slaves from Africa and putting them to work in the sugarcane fields.17 The left-over molasses had a lot of uses, but the primary use was in rum production.

The first recorded colonial production of rum comes from a 1552 report from the Portuguese colony of Brazil, which mentions slaves on sugar plantations being more willing to work and easier to control if allowed to drink a mixture known as “cachaco,” which indicates an alcohol for pickling rather than drinking, much like rum. Not wanting to deal with competitors to their own wine markets, colonial governments would suppress information about alcohol made from sugar. Eventually, word got out, and soon enough, colonies with access to sugar production began exporting rum, along with other molasses-based products.18 Rum and molasses then gained so much popularity, that the British would try to capitalize on it in their own Thirteen Colonies. Being the only item colonial inhabitants could get from non-English Caribbean colonies, molasses would be utilized not just for rum, but for other less important products as well. The British, wanting to reduce the competition their West Indian molasses producers and rum distillers faced, passed the Molasses Act of 1733. Due to its unpopularity, it was eventually retracted and replaced with the Sugar Act of 1764, which helped to inflame tensions that led to the American Revolution.19 So, how does Timothy Dexter’s warming pan scheme connect with the production of molasses? Well, the captain of the ship carrying the cargo actually found a use for the warming devices in that tropical climate. By adding handles to the covers of the pans, he sold them as molasses strainers for a high price, while the actual pans would be sold as ladles, also at a high price. In the end, a venture that by all accounts should have been a loss for Dexter, managed to make a profit, thanks to a centuries-old sugar production waste, or molasses.20

The warming pan incident wasn’t the only venture that Timothy Dexter took on. At one point in his life, he overheard a sailor complain about his shortage of “stay-stuff.” Dexter interpreted this to mean whale bones. After all, whale bones hold whale parts together, so why couldn’t it hold ships together? In any case, he bought up a large quantity of whale bones, but when he approached the sailor to sell him some, he was informed that stay-stuff is actually a term for rigging. However, luck was again with our Lord, as corsets made with whalebones was becoming more popular, enabling Dexter to sell his whale bone collection, again, for a profit.21 The illogical ventures turning up successful denied the Newcastle community of being able to say “A fool and his money are soon parted” in response to Dexter’s predicted failure. Once more, merchants tried to humiliate Dexter with another unsuccessful venture, giving him advice to, literally, “Carry coal to Newcastle,” which was an idiom for undergoing a pointless task, stemming from the fact that Newcastle is one of the world’s largest suppliers of coal. Timothy Dexter, as shown previously, didn’t have a lot of knowledge in regards to idioms, so he undertook the venture. Well, it turns out, just as Dexter’s coal shipment arrived in Newcastle, the coal miners went on strike, enabling Dexter to sell his coal at a premium.22

At this point, one might actually start to consider the possibility that Dexter was not the idiot everyone thought he was. While Timothy Dexter did have some business sense, he was nowhere near intelligent or witty, and his family is a prime example of this fact. Let’s start with his children. His son, Samuel Dexter, did very poorly in school, despite how much his father paid for his education. He would bribe others with his father’s wealth to be shielded from insults and to be granted education. At one point, having begged his father to be put in command of one of Timothy’s vessels, he sailed to Europe and betted all of his supply on the gambling table, losing it all. On his return, he entered into constant quarrels with his father and squandered all of his own money.23 Timothy Dexter’s daughter, however, fared a bit better, at first. She was a very beautiful woman, with a giggling personality. Her education was as useless as her brother’s, unfortunately. Her father’s wealth would bring to her many suitors, but all would turn away after actually visiting the father, due to his very un-aristocratic nature. She did eventually get married to a philosophical scholar, finding the scholar’s name in the papers and becoming attracted to the man’s intelligence. Even better, the scholar knew how to handle the massive red flag that was Timothy Dexter. Unfortunately, luck wasn’t as kind to either of the offspring as it was to Timothy Dexter. The scholar, having married in hopes of gaining wealth, found that Dexter did not give it out as freely as he had hoped, nor did Dexter’s daughter improve. As such, the couple had a daughter, who was raised to be successful by the scholar, and the two divorced, after which Dexter’s daughter returned to her father’s house.24

His relationship with his wife was also not ideal. The marital troubles between the two began almost as soon as Timothy Dexter moved into his mansion. When he opened his garden to the public for them to praise, several young ladies from the country would come into his garden and leave it decorated with beautiful flowers and carrying ripe fruit. His attempts at infidelity, however, would fail, as most of the women would reject his advances, seeing him as the man he was. At such occasions, he would stomp around the house and accuse his family of conspiring to make his life miserable.25 Eventually, the tension between the two grew so great, that Timothy Dexter turned his wife into a ghost, though not through murder. Instead, when asked about the woman to whom he was married by guests in his house, he would claim that the woman was, in fact, a ghost and that she shouldn’t be paid any attention.26

Alongside his unconventional way of making his wife stop bothering him, Dexter was also very arrogant. He was arrogant enough to the point of hiring a poet named Johnathan Plummer. The poet would write poems about Timothy Dexter, and praise him in elegant prose. Being an associate of Dexter, Johnathan Plummer also had his own eccentricities. Johnathan’s primary occupation, before writing for Timothy Dexter, was fishing. His side job involved selling “contraband literature.”27 In another instance, on Hampton Beach in New Hampshire, Timothy Dexter would tell the history of the self-proclaimed “greatest man in the East” to anyone who would listen, and most often they would, as they found Dexter to be a very amusing individual. On one such occasion, a playful girl would entertain herself while in his company by listening to his stories, but eventually, for reasons unknown, Dexter would assault her and chase her to her male friend’s carriage. Now, this male friend was a massive individual, strong as well, and when he heard the complaints of his friend, he grabbed Dexter and, sitting himself on the steps of the carriage, bent the greatest philosopher in the world over his knee and spanked him, like one would do to a child, enough to the point that Dexter began to bleed all the way down to his heels. This incident made him keep on his best behavior for a time.28

His arrogance often combined with his stupidity and rashness, to produce interesting results. The most interesting took place when Timothy Dexter ordered the painting of the statues on his property. One such statue was of Thomas Jefferson. Dexter, upon approaching the partially colored statue, saw the painter writing the fact that Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence. Seeing this caused Dexter to immediately “correct” the painter by telling him that Jefferson was the author of the Constitution, an exceptionally apparent mistake when taking into account that, at this time, it had been under twenty years that the Constitution was penned. The painter argued that what Dexter actually meant was the Declaration, and the argument got heated until eventually Dexter went inside in a huff. Figuring it was the end of the argument, the painter returned to his work, beginning to write the letters D, E, C, when suddenly a gunshot rang out, causing the painter to jump up in surprise. Dexter had come back outside, and fired a shot upwards into an archway. Henceforth, the statue read that Jefferson was the author of the Constitution.29

In perhaps his greatest display of arrogance, Timothy Dexter even faked his own death, so that he could watch his own funeral. Before this, he had ordered the creation of a massive tomb to rest in his garden, which was to be used when he actually did died. He then distributed news that he had passed and of the funeral to be held. From a hidden location, Dexter observed the group that had assembled itself before his casket that he had placed in the parlor. Among them was his wife, who wasn’t crying, most likely on account of the poor relationship between the two. This prompted Dexter to emerge from hiding and beat his wife with a cane, in front of the entire procession.20

Once nearing the actual end of his life, Timothy Dexter wanted to leave for himself a legacy, a way for future generations to remember him by. As such, he penned his memoirs in the form of a book titled A Pickle for the Knowing Ones, or Plain Truths in a Homespun Dress. Much like one would expect, it was a barely legible mess, even with given lenience for the lack of grammatical correction software. The issues are almost immediately apparent with the first page. “Ime the first Lord in the younited States of A mercary Now of Newburyport it is the voise of the peopel and I cant Help it and so Let it goue……Now I be gin to Lay the corner ston and the kee ston with grat Remembernce of my father Jorge Washington the grate herow 17 sentrys past….” 31 To summarize the book, it is more akin to a collection of Dexter’s writings about his view on life and his complaints about society as a whole. For instance, he wrote how he feared that the well-off, well-educated would exploit the hard laborers.32 The topics of his writings would also shift to his unhappiness with his family.33 Despite the poor grammar and lack of punctuation apparent throughout the book, the first edition sold well, justifying the sale of a second edition.34 To address the complaints about the lack of punctuation, Dexter would fill a page with commas, periods, and exclamation points, so that those with complaints could place the marks wherever they pleased.35

In the end, Timothy Dexter did die, like all men do, on October 26, 1806, living longer than his indulgent lifestyle was thought to allow.36 Part of this can be attributed to the work of his nurse, African-American Lucy Lancaster, whom Dexter believed to be descended from some royal African prince, according to the claims of her father. Not only was Lancaster able to care for the eccentric lord in his final days, but she also took part in caring for the mess that was his family, resolving quarrels between them, preventing the son from indulging too much in his crazy fits, and keeping the daughter out of the public’s eye. Lancaster would even give Dexter’s mind more credit than anyone else, seeing Dexter as a very honest man who never took advantage of his workers. If Lucy Lancaster had not been serving Dexter in the time she did, then by all accounts, Timothy probably would have indulged in much more ludicrous activities, especially as his mental health deteriorated with his physical health.37

In his final days, he would try to the best of his ability to atone for his sins, providing not just his offspring with an inheritance, but his extended family as well. Even his wife, whom he hated, received wealth from his last will and testament.38 In a twist of irony, the elaborate tomb that he had commissioned for himself was not his final resting place. The Board of Health, fearing the nuisance that could be caused by having a dead body in such a public place as Dexter’s garden, buried him in the most crowded graveyard of the time, the Hill cemetery in Newburyport.39 For how lucky he was in life, it’s quite ironic that he wouldn’t share that same luck in his corpse form. In either case, with his death comes the end of our protagonist’s journey, a man who became famous, or more accurately, notorious, for his rise in wealth due to happenstance, his arrogance despite this, and his overall lack of knowledge or class. While he isn’t as remembered today, outside of small groups of historians, he still serves as underlying proof in the faults of the idea of the American Dream, though in the opposite direction. In the United States, even as far back as the 1700s, the main determinant of whether or not one becomes wealthy is not hard work, morals, or skill, but is instead, luck. It just so happens that Lord Timothy Dexter was dealt the right amount of luck so as to transform himself into the greatest “philosopher” in the world.

I would first like to thank my supervising professor, Dr. Bradford Whitener, for helping me get this article where it needs to be, including helping me to tackle this new article format correctly. Without him, this article probably wouldn’t be of the quality it is now, nor would I have received this amazing opportunity to write about historical events and peoples not often covered. I would also like to thank St. Mary’s University Librarian Diane M. Duesterhoeft, for helping me find quality sources for this article. I would also like to thank the tutors I consulted in the early stages of writing my article, Amanda Uribe, who helped me in my initial search for sources, and Christopher Hohman, who helped me to correct my citing and overall project proposal. Finally, I would like to thank whoever is currently reading this, for reading about such a niche topic.

- Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter: With Sketches of the Eccentric Characters That Composed His Associates, Including His Own Writings, “Dexter’s Pickle for the Knowing Ones”, &c., &c (J.E. Tilton and Company, 1858), 15. ↵

- Deloraine Pendre Corey, The History of Malden, Massachusetts, 1633-1785 (Heritage Books, 1899), 98-99. ↵

- Gilman Messr, “Biography; Timothy Dexter,” Omnium Gatherum, June 1, 1810, American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collection: Series 1, 338. ↵

- Norman M. Price, “The Fabulous Luck of Timothy Dexter,” Collier’s Magazine, accessed September 2, 2021, https://jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.18886082. ↵

- Farley Grubb, “The Continental Dollar: How Much Was Really Issued?,” The Journal of Economic History 68, no. 1 (March 2008): 283, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050708000090. ↵

- Charles Scaliger, “America’s Inflation and Hyperinflation,” New American (08856540) 26, no. 21 (October 25, 2010): 35–37. ↵

- Eric Newman, “The Successful British Counterfeiting of American Paper Money During the American Revolution,” British Numismatic Journal, Third Series, 29 (59 1958), 174, http://www.britnumsoc.org/publications/Digital%20BNJ/pdfs/1958_BNJ_29_18.pdf. ↵

- Farley Grubb, “The Continental Dollar: How Much Was Really Issued?,” The Journal of Economic History 68, no. 1 (March 2008): 289, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050708000090. ↵

- Farley Grubb, “The Continental Dollar: What Happened to It after 1779?” (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, February 2008), 1, https://doi.org/10.3386/w13770. ↵

- Farley Grubb, “State Redemption of the Continental Dollar, 1779-1790,” July 2011. ↵

- Gilman Messr, “Biography; Timothy Dexter,” Omnium Gatherum, June 1, 1810, American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collection: Series 1, 338. ↵

- “$10,000 in 1790 → 2021 | Inflation Calculator,” Calculator, accessed October 19, 2021, https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1790?amount=10000. ↵

- F Gleason, “Lord Timothy Dexter’s House,” Gleason’s Pictoral Drawing Room Companion, October 11, 1851, American Antiquarian Society (AAS0 Historical Periodicals Collection: Series 3), 236. ↵

- “Lord Dexter,” Escritior; or, Masonic and Miscellaneous Album 1, no. 29 (August 12, 1826): 227. ↵

- Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter: With Sketches of the Eccentric Characters That Composed His Associates, Including His Own Writings, “Dexter’s Pickle for the Knowing Ones”, &c., &c (J.E. Tilton and Company, 1858), 33. ↵

- Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter: With Sketches of the Eccentric Characters That Composed His Associates, Including His Own Writings, “Dexter’s Pickle for the Knowing Ones”, &c., &c (J.E. Tilton and Company, 1858), 39-41. ↵

- Jean M West, “Sugar and Slavery: Molasses to Rum to Slaves,” n.d., 5. 1-2. ↵

- Richard Foss, Rum: A Global History (Reaktion Books, 2012), 25-27. ↵

- Gilman M. Ostrander, “The Colonial Molasses Trade,” Agricultural History 30, no. 2 (1956): 77. ↵

- “Lord Timothy Dexter,” Youth’s Companion 18, no. 24 (October 17, 1844): 94. ↵

- Norman M. Price, “The Fabulous Luck of Timothy Dexter,” Collier’s Magazine, accessed September 2, 2021, https://jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.18886082. ↵

- John Phillips Marquand, Lord Timothy Dexter of Newburyport, Massachusetts: First in the East, First in the West, and the Greatest Philosopher in the Western World (Milton, Balch, 1925), 96-97. ↵

- Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter: With Sketches of the Eccentric Characters That Composed His Associates, Including His Own Writings, “Dexter’s Pickle for the Knowing Ones”, &c., &c (J.E. Tilton and Company, 1858), 34-35. ↵

- Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter: With Sketches of the Eccentric Characters That Composed His Associates, Including His Own Writings, “Dexter’s Pickle for the Knowing Ones”, &c., &c (J.E. Tilton and Company, 1858), 37-38. ↵

- Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter: With Sketches of the Eccentric Characters That Composed His Associates, Including His Own Writings, “Dexter’s Pickle for the Knowing Ones”, &c., &c (J.E. Tilton and Company, 1858), 40-41. ↵

- John Phillips Marquand, Lord Timothy Dexter of Newburyport, Massachusetts: First in the East, First in the West, and the Greatest Philosopher in the Western World (Milton, Balch, 1925), 168. ↵

- John Phillips Marquand, Lord Timothy Dexter of Newburyport, Massachusetts: First in the East, First in the West, and the Greatest Philosopher in the Western World (Milton, Balch, 1925), 130-131. ↵

- Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter: With Sketches of the Eccentric Characters That Composed His Associates, Including His Own Writings, “Dexter’s Pickle for the Knowing Ones”, &c., &c (J.E. Tilton and Company, 1858), 43-44. ↵

- John Phillips Marquand, Lord Timothy Dexter of Newburyport, Massachusetts: First in the East, First in the West, and the Greatest Philosopher in the Western World (Milton, Balch, 1925), 262-263. ↵

- “Lord Timothy Dexter,” Youth’s Companion 18, no. 24 (October 17, 1844): 94. ↵

- Timothy Dexter, A Pickle for the Knowing Ones: Or, Plain Truths in a Homespun Dress (S. A. Tucker, 1881), 7. ↵

- Timothy Dexter, A Pickle for the Knowing Ones: Or, Plain Truths in a Homespun Dress (S. A. Tucker, 1881), 26. ↵

- Gilman Messr, “Biography; Timothy Dexter,” Omnium Gatherum, June 1, 1810, American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collection: Series 1, 340. ↵

- Timothy Dexter, A Pickle for the Knowing Ones: Or, Plain Truths in a Homespun Dress (S. A. Tucker, 1881), 4-5. ↵

- Timothy Dexter, A Pickle for the Knowing Ones: Or, Plain Truths in a Homespun Dress (S. A. Tucker, 1881). 26. ↵

- Gilman Messr, “Biography; Timothy Dexter,” Omnium Gatherum, June 1, 1810, American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collection: Series 1, 342. ↵

- Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter: With Sketches of the Eccentric Characters That Composed His Associates, Including His Own Writings, “Dexter’s Pickle for the Knowing Ones”, &c., &c (J.E. Tilton and Company, 1858), 106-108. ↵

- Gilman Messr, “Biography; Timothy Dexter,” Omnium Gatherum, June 1, 1810, American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collection: Series 1, 343-345. ↵

- Samuel Lorenzo Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter: With Sketches of the Eccentric Characters That Composed His Associates, Including His Own Writings, “Dexter’s Pickle for the Knowing Ones”, &c., &c (J.E. Tilton and Company, 1858), 110-111. ↵

23 comments

Robert Casselberry

Trenton, I am not surprised at all that you have become a great writer! This is a very interesting story that you tell very well….Keep up the good work!!

Carlos Hinojosa

This article was actually very interesting and got me entranced with it almost instantly. Honestly, I would kill to have luck like that, I mean that’s the equivalent of someone trying to sell winter jackets in Hawaii and then becoming a millionaire. Besides that this article got it’s point across and did a great job explaining why each of Dexter’s investments were successful.

Andres Ruiz

I read this and now I want to drop out of school and ship coal to Newport and buy Continental Dollars. Great read, and a hilarious story that left me incredulous and speechless

John Butler

I enjoyed reading this article I found the subject very interesting as I love obscure characters and how they affect history

Lisa

Wow! After reading about Timothy Dexter, my first thought was he “wasn’t worth a continental.” His only redeeming quality was hiring Lucy Lancaster. If not for her, in his final years he would have continued to be an arrogant, vulgar narcissist.

Trenton- I thoroughly enjoyed reading your article and I commend your writing skills. You have a gift for keeping the reader informed, entertained and wanting to know more. Thank you for a very well written piece and I look forward to more articles.

Allison

Excellent job! Keep up the great work, Trenton!!! Look forward to reading more of your work!!!

Thalia Kiolbassa

Clearly impressed with Mr. Boudreaux’s ability to convey his broad understanding of the subject. The details made this a captivating and informative read.

Heather

Excellent read! Kept me interested the whole article. Look forward to reading your future works.

Travis Green

A very good and informative article about one of the luckiest Americans to ever do it. I like how you go into detail about what he did and how he tried to atone for his sins when he was in his final days. His arrogance and stubbornness were well explained throughout his various schnanagins and decisions that should have ruined him financially.

Sally A Kalifa

Fascinating read! Keep up the good work!

Todd Pruetz

Wonderful article, written with style and knowledgeability that rivals seasoned authors! Very good read. I’m looking forward to Trenton’s future work.