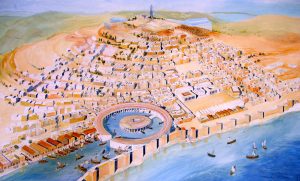

Carthage, a once powerful empire spanning from modern day Tunisia to almost all of the Iberian peninsula, had been reduced to a portion of its African territory. After two long and winding wars with the Roman republic, Carthage and its people were cowed by Rome, forced into a brutal treaty. Rome was not done with their old enemy yet, however. In 149 BCE, Rome would declare war again, setting off the events that would end in Carthage’s total destruction.

Immediately after the conclusion of the Second Punic war, the Roman senate discussed the war’s treaty and how to handle the Carthaginians going forward. Factions formed on how Carthage should be handled. Some wished for Carthage to be destroyed, while others wished to keep to the treaty Scipio Africanus had made, advocating for Scipio to be the judge of this endeavor. By the end of the debate, the pro-Scipio Faction won out.1 The thought of destroying Carthage, however, remained in the thoughts of many in Rome, and it would once again appear in the Roman senate, as Rome began to find a reason, any justifiable reason, to declare war on their oldest rival.2

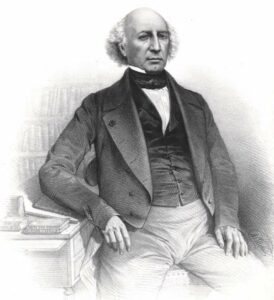

A Roman ally, Numidia, had been fighting Carthage over the disputed lands of Tyrsca, and a land called the “big fields” for years.3 Usually the Numidians, under Masinissa, achieved victory. On the other hand, Carthage, under the general known as Hasdrubal, received crushing defeats. As a consequence of these disputes, a Roman envoy was sent to Africa, intending to resolve the issue. Among these men was a Roman politician named Cato the Elder, who expected to see Carthage still recovering from the Second Punic war. However, contrary to his expectations, he saw a bustling city, rich in both wealth and in number. They took notes of both the estates and the land. When the envoys returned to Rome, Cato became tied firmly to the idea that Carthage must cease to exist, and from then on expressed consistently that Carthage must be destroyed.4

In the year 150 BCE, Carthage suffered an embarrassing blow at the hands of Numidia. Out of 58,000 men in a particular battle led by Hasdrubal, only a few were able to return to Carthage alive. The information of this weakness eventually made its way into the Roman senate, and Rome began calling up troops along the Italian peninsula. The Romans didn’t state what the army was for, but Carthage knew it was for them.5

Panicked, Carthage sentenced anyone associated with the war with Numidia to death, including Hasdrubal. By doing this, they hoped to shift all blame of the war to them, instead of to Carthage as a whole. They also sent envoys to Rome. One envoy blamed his citizens for taking up arms too quickly. In response, a Roman senator asked why they waited until the war’s end, instead of at the beginning, to condemn the members of the war, and why they waited until now to send ambassadors. The envoy had no response. Because of this, and because Rome still sought an excuse for war, the Roman senate deemed the answer unsatisfactory, and shocked, the envoy appealed to them again. The senate responded that Carthage must make it right with the Roman people. To do that, they would have to pay more tribute, and give up the disputed territory. With the envoys ending in total failure, they went home.6

As Carthage prepared for war, the people of Utica, seeing the events unfold in front of them, offered themselves up to the Romans.7 This provided Rome with a valuable port with which to dispatch troops. The Roman army came from Sicily, numbering 80,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry. The fleet accompanying them consisted of 50 quinqueremes, ships with five rows of oars, and 100 hemiolii, with one and a half rows of oars. Around the same time, Rome’s new envoy to Carthage gave both the news of their declaration of war, and that the fleet had already set sail for Utica.8

As a final desperate diplomatic act, Carthage attempted anything they could, sending envoys and ambassadors willing to bow down to almost all Roman demands. They gave 300 children away as hostages, and surrendered their weapons to Rome. Rome demanded more and more unreasonable acts from Carthage, fully intent on war. Finally, as the Carthaginian envoys were at the Roman camp again, Rome demanded that Carthage move their entire city. Censorinus, the Roman speaking for this cause, said “Your ready obedience up to this point, Carthaginians, in the matter of the hostages and the arms, is worthy of all praise. In cases of necessity we must not multiply words. Bear bravely the remaining commands of the Senate. Yield Carthage to us, and betake yourselves where you like within your own territory at a distance of at least ten miles from the sea, for we are resolved to raze your city to the ground.”9. To meet this demand, Carthage would have to uplift their roots and their lives and move at least ten miles inland. This would also destroy their way of life, as they were traders, using the sea to reach far away lands to sell goods.

As the Carthaginian envoys returned, their expressions caused the both Carthaginian senatorial assembly and the people of Carthage erupted in disbelief and panic, before the news was heard. Some Carthaginian citizens attacked both the envoys and Italians within the city, the envoys for bringing the bad news. The Carthaginians would resolve to fight, and on the Roman side, the consuls took their time preparing.10

That same day, Carthage sprung into action. They declared war on Rome and freed their slaves. The Carthaginian senate declared Hasdrubal their general, the same person who they had condemned to death about a year earlier. He quickly gathered 30,000 men. Another general named Hasdrubal was chosen for the defense of the city walls. Each day Carthage made approximately 100 shields, 500 darts and javelins, 1,000 catapult missiles, and as many catapults as they were able to make. Rome’s consuls of that year, Marcius Censorinus and Manius, moved slowly. They felt no need to move speedily as Carthage had already surrendered their arms. However, they found a city ready to fight, and they had to dig in for a siege of Carthage.11

The first battle of the war was initiated by Censorinus, who ordered the Roman troops to scale the Carthaginian walls with ladders. But, surprised by the amount of weapons and the spirit that the Carthiginians had, failed to take the city. The offensive general Hasdrubal also pitched a camp behind a lake also behind Roman forces. Both Roman consuls and their forces made camp after this battle, not willing to be caught off guard. Censorinus, needing resources for siege machinery, and ladders in particular. He sent men to the other side of this lake to collect wood. This is where another Carthaginian general, Phameas, entered into the war. As leader of the Carthaginian cavalry, while Roman soldiers were foraging, and in loose formation, he descended upon them, causing 500 Roman casualties. Unable to stop the making of siege machinery, however, Rome made another attempt at the wall, only to be rebuffed a second time. After this rebuff, Censorinus gave up the attack for a while. Manius also gave up his assaults on the wall; however, his efforts were feeble at best.12

The next battle, chosen by Censorinus, centered around two massive battering rams. With 6,000 foot soldiers and military tribunes, Censorinus was able to successfully knock down a section of the Carthaginian outer walls. Before being able to fully sally into the city, however, Censorinus’ men and the battering rams were forced back. During that night, Carthage’s troops sallied out and burned the battering rams, rendering them useless.13 The next day, before Carthage was able to finish repairs on the wall, two unnamed Roman tribunes forced their way into the city with their troops. Carthage prepared for this by utilizing the roofs of houses and the small streets. They began to force the military tribunes back, beating them in battle. The losses would have been much worse if it weren’t for one military tribune, Scipio Aemilianus, who was able to save the troops from destruction.14

Rome’s war wasn’t going well; however, it got worse as disease, caused by lack of fresh air, began to spread around Censorinus’ camp. In turn, he had to move his camp further down near to the sea. Carthage then took advantage of the direction the wind was flowing, and sent fireships down to the Roman fleet, nearly destroying it entirely. The Roman fortunes dipped further as Censorinus sailed back to Rome to oversee the consular election of that year. Emboldened, Carthage increased its pressure on Manius. They sallied out at night again, tearing down the Roman palisades. Amidst the confusion of the assault, Scipio Aemilianus was able to confuse the Carthaginians, and concerned them with movements on horseback, forcing them to flee back into the city. A second time, Scipio Aemilianus had saved Roman soldiers. Manius would be much more careful from this point onward, but that wouldn’t stop Phameas from raiding his foraging parties.15 He would avoid Scipio Aemilianus, who began deploying his troops in a different formation.16

During the near end of Manius’ career as consul, he decided to attack Nempheris, where the offensive general, Hasdrubal, was stationed. Scipio Aemilianus opposed the action. The path Manius was to take was filled with crags and thickets, perfect places for an ambush or attack. However, he was outnumbered by the other military tribunes, who voted to continue the expedition and move forward. Predictably, after great slaughter on both sides, Rome fell back across a river and towards the ambush area, and many romans were killed in the subsequent engagement. Among them were the military tribunes who voted against Scipio Aemilianus. Scipio was able to rally 300 horsemen, and used probing attacks against the Carthaginians to fight them off. But as they neared their camp, Phameas fell upon them with his forces, killing more Romans. After some more notable failures in attempts to attack the same location, Manius would be replaced.17

During the second retreat of Manius, Scipio received a letter asking him to meet at a certain place in the middle of the night, and bring as many men as he pleased. Scipio knew this letter was from Phameas. He was willing to switch allegiances with about 2,200 horsemen. With a single diplomatic move, Scipio Aemilianus had robbed the Carthaginians of their best cavalry general. Manius, back from his second retreat from Nempheris, no longer considered his movements a total failure. However, he and Censorinus were still replaced in 148 BCE by the new consul, Piso, and his consular colleague. A new admiral, Mancinus, arrived as well. Piso’s first action was to attack neighboring towns not belonging to Carthage, angering their inhabitants greatly. His second action was to attack Hippagreta, failing to take it after an entire summer, around three months worth of siege. All these failures allowed Carthage’s citizens to have reduced fear. Appian states that their citizens began to roam the countryside without fear of attack, making speeches to poke at the failures of Rome’s war.18

All of Scipio’s successes, accurate predictions, political maneuvers, and military expertise gave him great renown within Rome. It was with this fame that, with the next consular election of 147 BCE, Scipio Aemilianus was elected consul, despite being too young for the position within Roman Law.19 The consuls at first opposed this, but one of the people’s tribunes stated that he would see to it that Consular power was reduced unless they agreed to the election. The consuls ceded this point, and Scipio became a consul with all power at his disposal. He was allowed to conscript men up to the amount of losses received in Carthage, among other powers. From this point until the end of the war, Scipio Aemilianus would be the most prominent general in the war against Carthage.20

Scipio’s first action was to save Mancinus from another military failure. After an attempt by the Romans to secretly scale a neglected portion of the wall via ladders, the Carthaginians sallied out to push them out. The Carthaginians, however, were pushed back by Mancinus and his men, who pursued them into the city. Many of the Romans who pursued the Carthaginians were unarmed, and were spurred on by a chance of victory they had not yet gotten. When night fell, he camped next to the wall, knowing that the following morning, he would be attacked from all sides. He sent messengers out, urging Piso or any other able Roman to save him from his predicament. In the morning, he was attacked from every angle, having only 500 armed men and 3,000 unarmed. Scipio came to his aid, using the ships at his disposal to sail to the walls with all haste from the sea. The Carthaginians knew he would be coming, as the previous night, Scipio released Carthaginian prisoners to give them the news. Having this knowledge, the Carthaginians slowly began to withdraw from battle, and the Romans, along with Mancinus, were able to escape. This would be the last battle Mancinus would see in the third Punic war, as he would be sent back to Rome, no longer a consul or a general of these armies. Scipio Aemilianus would then camp not too far from Carthage, with Hasdrubal and the new cavalry general, Bithya, setting up a camp opposite of him.21

Before Scipio’s finest hour, he would have to sort out the troops given to him by the previous consuls. Due to Piso’s failures, the soldiers were idle, demoralized, and suffering from extreme greed. He called these troops together, and gave a speech to rally them and raise their morale, hoping to get them back to the strength that Roman soldiers were known for. He would berate them with words in the first part of this speech, saying “You are more like robbers than soldiers. You are runaways instead of guardians of the camp. You are more like hucksters than conquerors. You are in quest of luxuries in the midst of war and before the victory is won.“22 But he would follow up these words by saying he would overlook the past, and that he was not there to take money before victory was assured. Those who obeyed him in this war would be rewarded handsomely, while those who failed to obey him would get near to nothing.

This gamble worked. After his speech, he purged the army of useless men, expelling them from the camp, and restoring discipline to the remaining troops. Thus, he began his war movements against Carthage. First, he planned to capture a large suburb called Megara, next to the city wall. Moving by night and with the most silence a large army could muster, he split his army in two and surrounded the area, getting extremely close to the walls without being spotted. Once he was spotted, and the Carthaginians raised the alarm, both of his armies shouted back in full force, and began to scale the wall. Using a nearby tower to get onto the walls, Scipio’s troops were able to open the gates, and take Megara. Once in the city, he decided to make camp, not willing to risk his gains. He also set fire to their camp, which was abandoned now that he had taken Megara. The Carthaginians retreated to Byrsa, an area within the city with more fortifications and another wall. Out of revenge for the lost part of the city, Hasdrubal slaughtered Roman prisoners of war. Scipio Aemilianus had breached Carthage, and held it in his first attack. He had accomplished something that previous consuls took their entire year trying to do.23

From here, Carthage began to be starved out. A famine began to set in as Scipio closed all routes into the city except for the interior of Africa. Merchants ceased appearances, and the citizens were kept inside the walls, due to the siege that Scipio now orchestrated. Hasdrubal made the decision to use the scarce amounts of food to feed his 30,000 soldiers. After a few indecisive naval battles, Scipio decided to capture Nempheris, the same city that escaped capture before, this time making use of his Numidian allies. During the decisive battle, the joint Roman-Numidian force was able to capture the city of Nempheris. Now, during winter, Carthage was starved of basically all food, as their last supply route had been taken, and the winter storms closed off the harbor.24

Once spring had returned, Scipio was able to take Carthage’s inner harbor. The guards, weak from hunger, were unable to stop the Romans, who were coming in from all possible sides. He also took the nearby temple forum, and stayed there for the night. From there, he focused his sights on Byrsa. This part of Carthage was a fortress, and the six story houses were prefect for the Carthaginians to lob javelins, spears, rocks, and other objects from. Scipio’s troops scaled the walls, then made temporary bridges to reach the roofs. From there and on the ground, a bloody, bitter battle ensued. Each street had to be fought for, as well as each roof holding Carthaginian troops. Fire began to spread as Scipio ordered the streets he took to be put to the torch. This type of brutal street to street fighting carried on for six days. Scipio’s troops had to fight in shifts, being changed out from time to time. This was to make sure they wouldn’t be entirely worn out by battle’s end. Scipio himself, however, had very little sleep, running from battle to battle and place to place. He fully expected the carnage to continue for a while longer, but on the seventh day, he was approached by Carthaginians with a wish to talk. They asked Scipio to spare the lives of those who wished to leave Byrsa, and he accepted, for all except the military deserters. Nine-hundred of those deserters, along with Hasdrubal and his family, fled to the temple, then later to the shrine itself. It was here that Hasdrubal presented himself to Scipio privately, also wishing to talk.25

It is said that during this talk, Hasdrubal’s wife spoke ill of him and spoke more highly of Rome than her country’s defender. She took her children and killed them, throwing them, and then herself, into the shrine’s fire.

Scipio Aemilianus was now the conqueror of a city that had been alive and flourishing for over 700 years. Once rich in all manner of resources, and in a perfect location for trade and commerce, it was a city to behold, a rival of Rome. For three years, it and its people fought off many Roman attempts to put an end to it. Now, the city had been reduced to rubble, and Scipio was the one who had orchestrated the destruction of the great city, and the empire that hosted it. It is said that while witnessing this spectacle and taking it all in, he shed tears, reflecting on the rise and subsequent fall of empires, men, and cities. His words, according to Appian, were the words of the Iliad: “The day shall come in which our sacred Troy and Priam, and the people over whom Spear-bearing Priam rules, shall perish all.”26 It is believed that here, Scipio Aemilianus was referring to no other empire than Rome. Polybius, his tutor, is also recorded to have said that he was referring to his own country.

Now that the war was over, Scipio gave his men a certain amount of days to grab the spoils of war, plundering the once venerable Carthage. Those who showed bravery received prizes and gifts, and Scipio sent a ship over to Rome to let them know of their victory. Rome was now fully unopposed in the Western Mediterranean, having destroyed the only empire that could have opposed them there. Scipio Aemilianus would return to Rome and have a triumph, one of the highest honors a Roman can receive. Many Romans celebrated, and some rejoiced in the thought that they had now confirmed their worldwide supremacy. Games and spectacles were held, and Rome forbade the rebuilding of any part of Carthage at this time. From here until the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Rome would be fully unopposed in that region of the world.27

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 9. ↵

- Polybius, Histories, Plb. 36.2 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 10. ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 10.69 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 11.74 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 11.74 ↵

- Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, 49 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 11.76 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 12 ↵

- Polybius, Histories, Plb 36.7 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 13 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 14.97 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 14.97 ↵

- Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, 49 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 14.100 ↵

- Polybius, Histories, 36.8 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 15 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 16 ↵

- Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, 49. ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 17.112 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 17 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 17.116 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 18 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 18 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 19 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 19.132 ↵

- Appian, The Punic Wars, chapter 20 ↵

15 comments

Michaell Alonzo

Hey Matthew, congrats on your nomination for an award for your article. This post was so beautifully written and fascinating to read. It demonstrated that despite our desire for peace, it seemed to be impossible to achieve in the violent world we already inhabit. This page has an astonishing quantity of specific information. The pictures you selected were fantastic and completely complemented the narrative you were delivering.

Kristen Leary

Congratulations on the nomination! It’s no wonder it was nominated for best descriptive article because it’s nothing if not descriptive. I think you did very well in capturing and relaying the views they had of each other and what moved them to attack in the ways they attacked. Well done on a very interesting and well written article.

Alia Hernandez Daraiseh

This article is very well written and structured beautifully, and there was a lot of descriptive detail that made the article flow. I learned a lot of information from this article, as I did not know much about the history of Carthage. It’s really interesting to know how they kept allowing things to happen just to avoid conflict.

Helena Griffith

Thank you for the nomination! It is strange to imagine that individuals actually intended to kill another city and its inhabitants because of an ancient animosity, which was sparked when they noticed their adversary was prospering following the war. It’s tragic that Carthage was so anxious to put an end to the conflict that they simply kept accepting additional conditions until they were unable to accept any more. Really well written and fascinating.

Joshua Marroquin

I am amazed on how well structured and organized this article is. I am not too surprised that this article was nominated since it is amazing how descriptive the article is. I can’t believe on how much I learned from reading this passage. For example, I learned that the Carthage was willing to do anything just to put a stop to the on-going war.

Ana Barrientos

Wow! Congratulations on your nomination! This article was absolutely fascinating and well written. The amount of detailed information in this article is amazing. I also loved the images you used, it really tied into the story you were telling. I have heard of the Punic Wars before but never took time to research them, your article taught me something new! Overall, awesome job!

Mateo Ortega-Rios

First of all, congratulations on your nomination! This whole article is very appealing and attracted my full attention. The details were able to paint a picture in my head. And it is interesting how because of a rivalry they wanted to destroy everything that they had. The structure of the whole article is something that makes this article very appealing for me. I really like the title because of how straight forward it is.

Shecid Sanchez

Congratulations on your award nomination! This was such a well written article and so interesting to read. We live in a world full of violence and it showed that we will always be living in a world where there is no peace between us. It has always been a problem with people to want to harm their enemies and how anger usually results in violence and how things escalate so quickly.

Lorena Maldonado

This was a very informative article and I enjoyed reading it. Personally, I had never heard anything about this story before, so it was definitely interesting to read about it. It was very detailed and shows how human nature can cause the destruction of empires. This was definitely deserving of an article as well and you did a fantastic job writing it.

Brandon Vasquez

Congratulations on your nomination! It did not surprise me that this article was up for an award. The rivalry between Rome and Carthage is one of the greatest in history. I think just the idea of conquest was what pushed this from the Romans and even though terms kept being met total destruction was the main goal.