Yet another orchard inaccessible.1 John had tried to trek far into the frontier to plant apple tree seedlings, so he could sell to future pioneers. But the migrants moved in before John could officially claim the land.2 Did he need to? His business model of planting seeds wherever he wished had been working thus far. How was he to make money off his seedlings if they were on another man’s property?

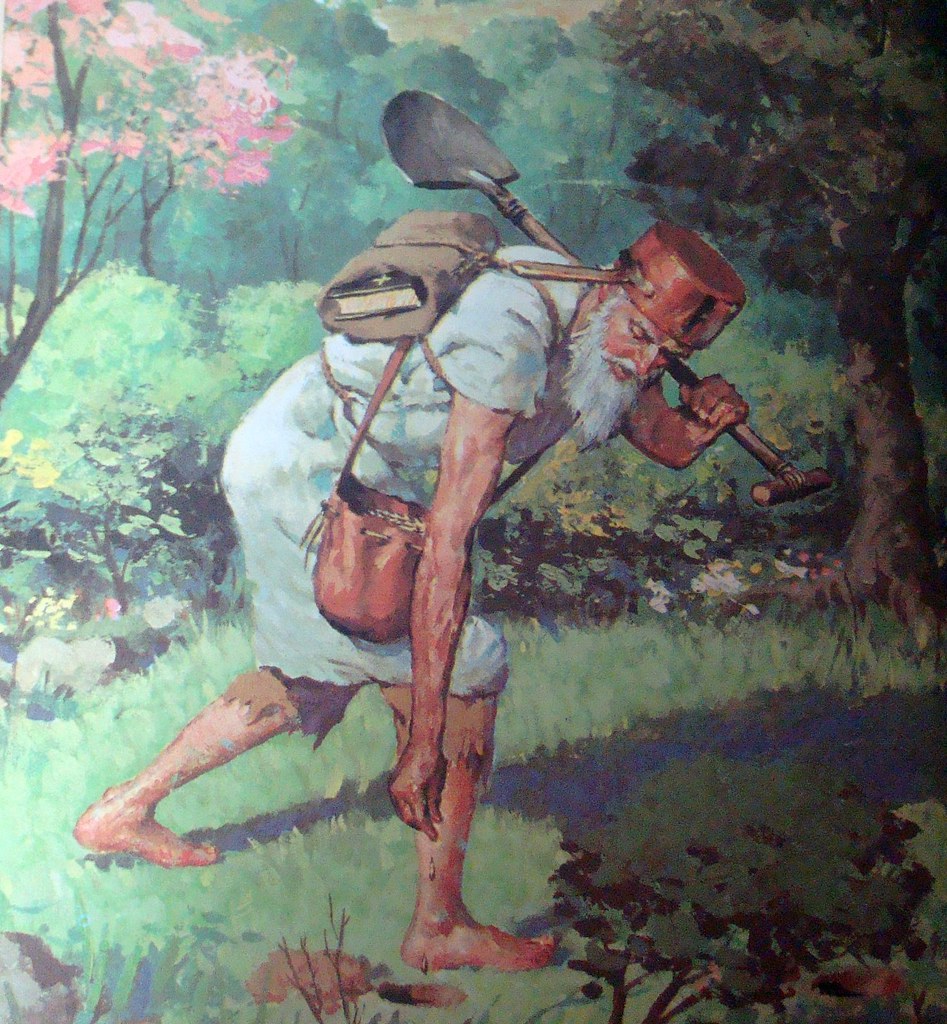

John Chapman, later known as Johnny Appleseed, was an unconventional man all around. Not only was he extremely frugal—wearing a coffee sack as clothing, and he often walked barefoot.3 Not only was he a missionary for offbeat theological views—as he belonged to the New Church, a Swedenborgian sect of Christianity that believed the Second Coming of Jesus Christ had already occurred in 1757.4 But he was also unaccustomed to making cash transactions and formal land agreements.5 This was due to the environment in which he grew his business.

John Chapman started with nothing, though. While he was the eldest son of his family, he did not stand to inherit any land. His father, Nathaniel Chapman, made the difficult decision to put the family land up for sale long before John would have been able to maintain it. The Chapman family desperately needed the money that selling the land provided.6 This is especially true since the family kept growing. John’s stepmother, Lucy Chapman, gave birth to ten children in the years he was growing up in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. This gave patriarch Nathaniel Chapman a total of twelve children, all living in his four hundred square foot home.7

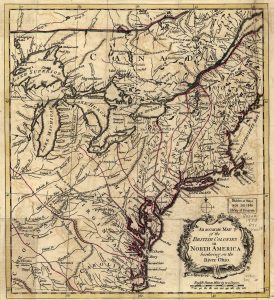

The constant clamoring of children, the lack of space, and the desire for land of his own gave John the energy he needed to set out in search of his own future. By the age of twenty-two, John set out West with his half-brother Nathaniel.8 The Chapmans could not simply head west and claim land. According to many land acts, like the Pennsylvania Land Act of 1792, pioneers were required to improve land in order to rightfully call it theirs. The government wanted to be sure migrants who claimed land were going to stay there for a long time. This resulted in the building of log cabins, clearing the land, and planting orchards and gardens.9 Luckily, John Chapman had a plan. Having spent time in Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania during the 1770s, John would not have been a stranger to apple orchards. Many orchards were planted here as proof of improvement.10 So, before trekking across the Allegheny mountains, the brothers stopped at cider mills.11 Since cider-making season ended in November, John was able to rummage through the left-over pomace and gather thousands of seeds for free. Even though this would cause the brothers to travel during the harsh winter, it was worth the risk for John.12

While the trip was not easy, Native Americans proved that crossing the Alleghenies from Wyoming Valley was very possible. In fact, they created a valuable system of trails.13 These trails were made to cross sources of water, and they were set on kind ground, not too jagged or steep. The Chapman brothers were also sure to have shelter every night. They stayed in existing shelters previously created by Native Americans.14 While Native American knowledge was an advantage to John Chapman, migrants like John were not music to the ears of the natives. The western migration of Americans threatened to displace Native Americans in the region, like the Iroquois. Natives struggled to deter these migration patterns, but it would be no use.15

John concluded this journey in western Pennsylvania, specifically in the town of Warren.16 While many Americans looked down upon the ways of the Natives, migrants needed to learn from them. The land on the Western frontier was not suitable for ranching and agriculture. Forests were dense and the land with fertile soil would flood annually. As a result, Americans learned to survive off the land like the natives of the region. Despite folktales asserting that Johnny Appleseed was averse to hurting animals, John, like other frontiersman, hunted for much of his food.17 Chapman also took up the Native habit of tapping sugar trees. A ledger from a store in Brokenstraw Creek, near the town of Warren, makes note of John’s purchase of a gimlet, which would be used to gather sap from maple trees.18

In fact, John Chapman planted his first apple tree nursery in Brokenstraw. This was all part of the business plan he would use for decades to come. First, John established apple tree nurseries, like the one in Brokenstraw.19 Because these plants did not require much upkeep, he was able to travel to different areas of the frontier and plant more nurseries. Later, once the saplings were about three years old, Chapman could sell them to families who recently migrated into the area.20 These families could then plant them on their land and fulfill the improvement requirements for setting a claim to land in the west.21

Another advantageous business move made by John was his effort to stay in the good graces of surrounding land companies. These land companies, like the Holland Land Company in Western Pennsylvania, bought up much of the acreage in the West once land acts, such as the Pennsylvania Land Act of 1792, were passed. These groups were weary of American migrants like John Chapman encroaching on their territory. They feared these pioneers would work their land without compensating the company.22 However, migrants were helpful to land companies as well. They helped fulfill land improvement requirements, which allowed the company to retain the land. In exchange for a title to a piece of land, land groups doled out tracts to migrants who were then to build cabins, clear forests, and plant crops there.23

John was part of the useful bunch. Chapman, known for his ability to swiftly cut down trees, was likely a logger for the Holland Company. John also performed a cattle drive for the company. In exchange for labor, the company paid off John’s tabs at his local general store multiple times.24 Since John never tried to settle on Holland Company land himself, they were more than willing to let him plant his apple seeds in the region. His seedlings would prepare the land and make it more enticing for future settlers.25

However, Johnny could not hold onto any Holland Company land he tried to settle on. While he had a good plan for his apple tree seedling business, he was not scrappy enough to fight for it. Those who knew him described John as a meek, kind, sensitive man. R.I. Curtis was just a young boy when he knew John Chapman, but he recalled John taking a beating from a man whom John had minorly inconvenienced. Even though John was much larger than his attacker, he did not fight back due to his kind nature.26 Also, at the turn of the century, more families than single men began migrating to western Pennsylvania. Men who were already the head of a household had more at stake moving west. With their family in mind, these men would go to further lengths to secure a tract of land than a bachelor like John Chapman.27 Due to others jumping his claim on land and the fact that the frontier was on the move, John headed further west into Ohio.28

Although, there was one issue: Other people had the same idea as John. Many migrants were also having trouble making land claims in western Pennsylvania. Soon, orchards began popping up in the new frontier. In 1801, when Johnny crossed the Ohio River, he found that there was already substantial competition for his apple tree business.29 Once he arrived in eastern Ohio, a local man offered John Chapman a place to stay. The man loved the idea of bringing apple orchards to the area. He thought they would be of high value. However, John declined the offer. Just across the river in Wellsburg, Virginia, there were acres upon acres of peach and apple orchards. Twenty miles away on Wheeling Island, there were yet more orchards. Chapman could find more business and less competition further west. So, he continued on.30

This was a struggle. By the time John arrived, multiple varieties of apples were available to the residents of Cincinnati. So, he persevered west. Local tradition boasts that Johnny Appleseed had a hand in the planting of apple orchards in Licking Valley. However, the wife of Isaac Stadden staunchly opposed these claims, saying that it was her husband’s effort alone. And, anyway, John kept moving.31

In his travels, John had trekked all over modern-day Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana, but he eventually found his sweet spot.32 Since it wasn’t compatible with John’s business plan to completely settle down, John simply stuck to a general area of Ohio, specifically, around Owl Creek and Mount Vernon. Here, by the time his apple seeds had matured into seedlings, there were plenty of migrant families in need of proof of land improvement.33 Also, these migrants had many great reasons to buy from John rather than from any other planter. First, John’s seedlings were much cheaper than the others on the market. The price for one of John’s seedlings ranged from three to five cents and he was open to negotiation. Overall, John was lenient when it came to collecting payment. He understood that some debts would go unpaid, and that was the reality of life on the frontier. It didn’t matter much to John anyway. Since he collected his seeds from the discarded pomace of cider mills, they cost him nothing. John also performed all the labor for his orchards himself, so he never had to pay laborers. It wasn’t particularly grueling work either. In fact, John would plant seeds and leave them to grow for a considerable amount of time before he checked up on them again. The apple trees just didn’t require much attention.34 This did not produce the best possible yield, however. Wild animals and the occasional fire could eat away at the number of seedlings Johnny could sell. Still, enough grew to make a decent profit.35 John’s seedlings were specifically valuable to his clientele because they did not come from distant lands. Johnny planted many nurseries in different areas of the frontier. The growth from seeds to seedlings was proof that Johnny’s trees could thrive in the climate and soil in which they originated. Local migrants would have no doubt that these seedlings would thrive in their nearby land as well.36

Still, John faced one major problem: land claims. John remained a squatter even after his business began to flourish. On multiple occasions, Johnny would return to his apple tree nurseries to find that a new settler had moved on to the land and held the land title. At this point, all John could do was rely on the generosity of the new settler. Hopefully, the new settler would let John back onto the property to carry out his business.37 Would Johnny reap what he had sowed? Would each new settler sell Johnny’s seedlings as their own?

To add to this thought gnawing away at John’s mind, he could only be in so many places at once. His nurseries were spread about twenty miles apart from each other.38 While this was advantageous when it came to selling his seedlings, it hindered Johnny from protecting his nurseries. He could not ensure migrants would not swoop in and occupy his land. On occasion, John had made a deal with locals to keep watch of his nurseries and facilitate trade as he traveled the frontier. But this was not the case every time.39 And it was easy for informal agreements to fall through.40

He could only think up one solution. As was his nature, John meekly approached each migrant who had settled where he had previously planted. Each time, he used his resources in the area. In 1826, Chapman called upon John James, a fellow follower of the Swedenborgian religion. James was a well-respected man in the area of Urbana. Chapman hoped to use James’ credibility to come to an agreement with a settler who had moved onto one of Chapman’s nurseries. Whether Johnny was able to secure this nursery is unknown. What we can be sure of is that he went to these extents for many of his nurseries, and was able to profit from at least some of the land he worked.41

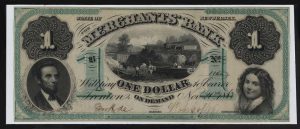

In the years following, John adjusted to the new American economy. Instead of relying on word of mouth, he began to make formal transactions. He purchased land and signed written agreements, which he made records of in county offices. John continued to be known throughout the region as amicable and generous, but this did not hold as much weight as it used to. When he was first starting out, reputation meant everything. This is because trust was important without documentation. In the new age of the economy where almost every transaction was documented, if Johnny did not conform, anyone would be able to pull a fast one on him. Beginning in 1826, we see that John began leasing land to plant his apple seeds on. In Ashland County he officially leased a half-acre plot of land for forty years.42 Two years later, he leased three more tracts of land for his nurseries in Great Black Swamp.43

So, John continued selling seedlings without the fear of losing the land he planted on. Migrants continued buying his cheap trees, which they could use to improve their land. John still faced some setbacks, being the quirky, sometimes overly-kind gentleman he was. But he seemed to find contentment and peace after he slowly but surely adjusted to the new rules of the growing American economy in the frontier.

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 150. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 64-65. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 140. ↵

- “Swedenborgian Church (Church of the New Jerusalem),” in Religious Holidays & Calendars (Omnigraphics, Inc., 2004); William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 104. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 88. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 34. ↵

- Howard B. Means, Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 33-34. ↵

- Howard B. Means, Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 39. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 51. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 38. ↵

- Nancy M. Gordon, “Johnny Appleseed.,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, 2022). ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 40. ↵

- Howard B. Means, Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 42. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 39. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 41-42. ↵

- Nancy M. Gordon, “Johnny Appleseed.,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, 2022). ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 47. ↵

- Howard B. Means, Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 54. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 51. ↵

- Howard B. Means, Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 75. ↵

- “John Chapman,” in Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, March 1, 2021. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 54. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 52. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 59. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 62. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 64. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 63. ↵

- Howard B. Means, Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 77. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 73. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 74. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 78-79. ↵

- “Appleseed, Johnny,” in Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia 2018 (World Book, Inc., Chicago., 2018). ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 83-85. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 88-89. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 86. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 89. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 86. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 89. ↵

- Nancy M. Gordon, “Johnny Appleseed.,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, 2022). ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 139. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 139-140. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 140. ↵

- William Kerrigan, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard: A Cultural History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 151. ↵

5 comments

Abbey Stiffler

was unaware of “Johnny Appleseed’s” real background or that he was a real person not just a name in a story. I was unaware of the effects of his straightforward business strategy. I believe that what really demonstrates resilience in him is his capacity to adjust to the shifting social norms and the economy around him. It is kind of frustrating and sad how he in a way got taken advantage of in some cases.

Alexandra Ballard

I didn’t know Johnny Appleseed was a real person! I thought it was just one of those folk names tossed around for fun. Such an interesting read to see how his life unfolded. His ability to adapt to the changing ways around him I think really shows resilience in him. I think his life is a testimony to how kind people will often get taken advantage of, especially in business.

Barbara Ortiz

Great Article Gabriella! I was not aware of the true history behind “Johnny Appleseed” and that it was a real person. I had no idea about the impact of his simple business model and venture would become responsible for much of the apple orchards of present day Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and even northern West Virginia. Or that this venture would be started at such a young age.

Mark Gallegos

Johnny Appleseed was a name I’ve heard of but never knew his story at all. This article was very well composed. I like the way you sectioned John’s story. As someone who has never read the folktales/books about him, it is strange to hear about his hardships like surviving as a squatter or having to deal with dishonest settlers.

Marissa Rendon

I loved reading Johnny Appleseed as a kid it was truly one of my most favorite books to read. In fact i still have a hard cover of this book. So reading this article was everything to me. its crazy to me that he was apart such american history in a way watching people own land that he wasnt ever going to be able to own