The study of history includes the study of war and weapon development. Since recorded history, war has been one of the greatest motivators for innovation since before recorded history. In fact, the Bronze age developed weapons systems that stayed in use until the Early Modern period, with weapons such as swords, axes, hammers, spears, and bows and arrows. One of the most critical weapons developed during the Bronze age was a piece of technology that was the direct ancestor of cavalry units. That technology carried the ancient world’s Homeric heroes into legendary duals and battles. Used for transportation, recreation, and war, they were the chariots. Most historians believe that the chariot became obsolete as early as the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BCE; however, that battle only marked the end of its long decline in the history of chariots in war.

Chariots were the Bronze Age measure of power to the ancient Egyptian and Assyrian empires, as were battleships and later aircraft carriers to the world powers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Following the simple philosophy of “the more superweapons a country has, the more powerful of a state it is compared to its rivals,” like the dreadnought of the twentieth century, the chariot was that kind of superweapon. It was at the battle formation center surrounded by support troops. Like the dreadnought battleships, the chariot also held a brief period in which it was supreme, before being surpassed by better weapons and tactics. Chariots were used heavily around the ancient world, stretching as far east as China in the Shang Dynasty and as far west as Britain.1

The development of chariots is as old as the wheel itself, coming into being during the rise of Mesopotamia. Traditionally, chariots were made from light wood and leather, and usually drawn by a pair of donkeys and early domesticated horses. At times, the horses that pulled the vehicle were the size of modern-day ponies, meaning that they were not large enough to carry a full-grown man. The chariots themselves started as basically four-wheeled wagons. Later they evolved into single axle vehicles. They followed four designs: Box, Quadrant, Dual, and Rail chariots. The latter was the most common one depicted in art; we see them commonly displaying scenes from Homer’s Iliad in ancient Greece. Within the Bronze Age powers, mainly those in the Near East, chariot riders formed a special class in society, as a minor nobility class like knights or samurai, as were also the craftsmen who made the ancient superweapons.2

The Bronze powers were not uninformed on the use of war chariots, favoring one of two styles of chariot fighting. A light one was meant for scouting, and it had a mobile platform for archery. This was favored by the Egyptians and sometimes referred as the Egyptian model. The other use for chariots was to use for them as shock units. Riding a heavy chariot would been a driver, a warrior with a shield and sword, and the third rider with a long lance. This was the chariot of choice for the Hittite Empire, where the term Hittite model was used.

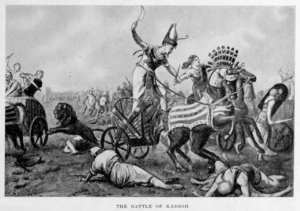

And these two different chariots had a chance to clash in the ancient world, in the wars between the Egyptians and the Hittites as they both pursued dominance over the known world. The greatest of chariot battles was the Battle of Kadesh. Much like the clash of Great Britain and Germany in the Battle of Jutland in 1916, the largest battle of dreadnoughts in history, the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE was the largest such battle of chariots, between the Hittite Empire and the Egyptian New Kingdom. Sources state that the conflict hosted somewhere between five to six thousand chariots. The battle was for the city of Kadesh in modern-day Syria. Both armies were infantry based, and each were practiced in combined arms of chariots, spearmen, bowmen. The battle was a strategic failure, but it was a tactical victory for the Egyptians due to the fact that Ramesses II and his army did not capture the city. However, the Egyptians did manage to destroy the Hittite army. However, thanks to Ramesses II being a great propagandist and lacking Hittite sources, most assume that it was a total Egyptian victory. As a result of the war between the two empires, the world first peace treaty occurred, including provisions for a mutual defense pack, mutual aid, and de-escalation of tensions, clauses that Egypt upheld when the Hittite Empire needed help a century later when a bad famine struck the nation.3

Another similarity of chariots to the dreadnoughts is that these warships with their large guns became obsolete shortly after the largest battle took place. So too with the chariots; they soon began to get replaced with men riding horses as cavalry. Chariots were no longer the prefect super weapon, with their best use being limited to large open fields. The ancient powers had to start looking for a more versatile tool of war.

And the solution was already found, and that was in the sovereigns’ guards, and aristocrats’ choice of mount, the horse. Even in the early days of the cavalry, they showed themselves able to preforming a diverse range of skills, from scouting to heavy stock units, while also being able to operate on a versatility of terrain that chariots cannot.

However, the horses used for early cavalry were the same as those pulling the chariots. They were small and strong enough to carry only a small amount of weight. They were not easy to control, with their riders mounting them bareback, and the only way to lead the horses was with reins. It was not until the fourth century BCE when the larger breeds of horses appeared in the Nisaean plain in Persia. These large horses could carry a heavy load, such as armor for its rider and itself, creating heavy cavalry. This heavy cavalry fathered the decline in the use of chariots in warfare. They remained a central battle unit, yet they were not fielded in such great numbers. The Chinese were the first to start using heavy cavalry during the War-State period from the fourth to the second centuries BCE.4

Another factor that ended the use of chariots, by another bronze-age power, came from the Greeks. Greece is mountainous, with limited arable land for growing crops and livestock. For the Greeks, and to a greater extent, the ancient world, the nobility were the only ones who could acquire horses. They were the only people who could afford the more massive horse breeds that make up war horses, since they owned the land that could sustain them. The small aristocracy limited cavalry troops to a small pool of talent, since people would not risk their horse being either hurt or killed, further shrinking horses’ reserve robust enough to be in the cavalry to fight a war. When they could raise enough to create a cavalry unit, the classical Greeks divided cavalry into three classes: Light, Heavy, and Mounted Infantry, or those who were able to fight both on foot and on horseback.

Most Greek city-states could only field a small number of cavalry units in a war. Macedonia was the exception. It was a kingdom in northern Greece where the land was more significantly plains and grasslands than in lower Greece—allowing the Macedonians to have a greater reserve of horses at their disposal. However, Macedonia’s kingdom was the outcast in the ancient Greek world, leaving the domain harassed by their neighbors and a tribute state to cities such as Thebes. They did this by holding a member of the royal family hostage. The forced guest lived extremely comfortable lives and were taught by some of the ancient world’s finest minds while captive.5

One such hostage was Phillip II, father of Alexander the Great, who reformed the Macedonian army to unify his country. The military was a standing professional army; one of them turned the cavalry from a support role to a direct combat role, bringing great success during Phillip’s early regime. He saw success in the Third Scare Wars, during 356-346 BCE, named because most of the fighting of this war was the City of Delphi, a great place of holiness for the ancient Greeks. It was fought against the Delphic Amphictyonic League, a confederation of Greek city-states in the northern regions of Greece, and the combined might of Athens, Sparta, Pherae, and Phocis. In 338 BCE, during the Battle of Chaeronea, Athenians were fighting the Thebans and Macedon. This was the first major battle for the now King Phillip II of Macedon’s young son, the seventeen-year-old Alexander the Great. The battle proved that Alexander the Great was an effective cavalry commander, but also cavalry was far more effective than chariots.6

After the Third Scare War and Greece’s unification, King Phillip II, hegemon of Greece, started to plan to reconquer former Greek colonies in Asia Minor from the Persians. However, Phillip II was assassinated in 336 while attending a party in Aegae, modern day Vergina, Greece, by a bodyguard and former lover. Shortly after the death of Phillip II, the Macedonian aristocracy elected Alexander as King of Macedonia, and hegemon of Greece. His father would not outdo him; Alexander the Great set his eyes to reclaiming Greek cities and the whole of Persia.7

In the year 336 BCE, Alexander the Great set out with his forty-seven thousand men to conquer the Persian Empire. During the conquest of Persia, there were three major engagements, including the battle that slew the chariot in battle. The conflict was near the small village of Gaugamela. The Persian army, led by the last emperor Darius, outnumbered that of Alexander the Great. Records vary from Darius’s army sources; he had between fifth-two thousand to one-hundred thousand men, including war elephants and scythed chariots.

However, the day before the battle, Alexander the Great took the mountain near the town, which allowed him to have an optimal location to monitor the Persian positions. During the night, while the Greeks rested, King Darius had his entire military force stand in rank and file for the night’s duration and for hours before the battle. Darius also had his whole strength stretched in a line to deny the Greeks outflanking tactics and with the bonus of enveloping the Greeks when fully engaged.8

In order to prevent defeat, Alexander the Great had to force the King of Persia to leave the battle, which would cause the entire Persians Army to be routed. Alexander the Great spread his forces thin to break the Persian formation, leading to his lines’ weakest part. After the internal volleys of missiles and rocks from both sides, Alexander the Great made the first move by leading a cavalry unit to the Persian’s right. To counter, Darius sent his left to attack with cavalry and chariots. That was what Alexander wanted; after a brief engagement, he fell back to his approaching phalanx troops.9

As the scythed chariots approached the central infantry unit, the Greeks employed the Mouse Trap tactic, designed by Alexander the Great himself. The tactic called for the phalanx center to fall back, allowing the chariots in the ranks. Simultaneously, the unit’s left and right close the opening and attack the vehicles’ rear. The Greeks flawlessly executed Alexander the Great’s tactic for those who fell into the trap—bringing the war chariot’s long military career to a crashing end. After the Greeks successfully deterred the chariot charge, it left Darius’s left weakened. That allowed Alexander and his cavalry to break through and attack the Persian King, causing the King to retire or risk being killed. Subsequently, the Persian Army fell apart. Alexander the Great would have given chase after Darius to either capture or kill him and earn the conqueror’s right to claim the entirely of the Persian Empire. However, he had to return to save his left units from being destroyed.10

After the Battle of Gaugamela, the chariot’s role fell to being solely ceremonial and for racing, never to be used in a significant combat role again. The chariot was the dreadnought of the ancient world. It was a weapon that every nation that could produce them had to have. They were a way to measure the power and wealth of a country. Similar to the dreadnought, the means of waging war changed and slowly turned chariots into being obsolete. But some continued to use chariots in war, such as the Celtic tribes of the British Isles used by chieftains and powerful warriors. The last recorded battle with chariots was in 84 CE, in the Battle of Mons Graupius, between the Romans and the Scots.11 But most civilizations and empires turned the ancient symbols of might and past wars into meaning of transporting people in cities and long distance travels, ceremonial roles such as the Roman Triumph, a military victory parade where the commanding general would ride a chariot. Even still, chariot racing become a popular sport in the Roman Empire, and with greater zeal in the Byzantine Empire.

- Aakanksha Gaur, “Chariot,” Britannica (website), May 3, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/technology/chariot ↵

- Invicta, Units of History – Mycenaean Chariots of the Trojan War DOCUMENTARY, August 13, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-TyVh8PlnS4. ↵

- Kings and Generals, Battle of Kadesh 1274 BC (Egyptian – Hittite War) DOCUMENTARY, September 10, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9b_Ab9GGb6g. ↵

- Aakanksha Gaur, “Chariot,” Britannica (website), May 3, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/technology/chariot ↵

- Invicta, Units of History – The Macedonian Companion Cavalry DOCUMENTARY, February 21, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bbLnrGGqyWY. ↵

- Donald L. Wasson, “Battle of Chaeronea,” World History Encyclopedia, accessed September 2, 2009, https://www.worldhistory.org/Battle_of_Chaeronea/. ↵

- Guy Griffith, Philip II | Facts, Definition, & King of Macedonia | Britannica, May 4, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Philip-II-king-of-Macedonia. ↵

- “A Contemporary Account of the Battle of Gaugamela,” Livius (website), 331, https://www.livius.org/sources/content/oriental-varia/a-contemporary-account-of-the-battle-of-gaugamela/. ↵

- Victor Ehrenberg, “Polypragmosyne: A Study in Greek Politics,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 67 (1947): 46–67, https://doi.org/10.2307/626781. ↵

- “A Contemporary Account of the Battle of Gaugamela,” Livius (website), 331, https://www.livius.org/sources/content/oriental-varia/a-contemporary-account-of-the-battle-of-gaugamela/. ↵

- Duncan Campbell, “British Chariot,” 2010, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/britannia/boudica/chariot.html. ↵