Introduction

Sovereignty, or the authority of a state to control itself, is a contested issue around the world. This is especially so for communities that have found themselves placed within a state’s political boundaries that they do not necessarily agree with. In many of these cases, sovereignty movements are also supported by the native language of a population, establishing a case for sovereignty. Some instances are the Catalonian and Basque regions of Spain as well as the conflict between Northern Ireland and its status within the United Kingdom (Campbell, 2010; Carnie, 1995).

Another place in the world where this occurs is in the state of Hawai’i which resides within the political boundary of the United States. The state has seen resistance against American rule by some Native Hawaiian groups, as well as the revitalization of the indigenous language. While the language revitalization of Hawaiian and the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement had different beginnings, there is a connection between them, as both are in response to the encroachment of American interests on Hawaiian sovereignty.

In recent times, the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement has become informed by and promotes the revitalization of the Hawaiian language. In turn, the revitalization of the Hawaiian language provides the ability to understand the aims and goals of the sovereignty movement. In this paper, I argue that while they are initially separate movements, the revitalization of the Hawaiian language and the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement are intertwined and have developed a mutualistic relationship over time. I will begin by explaining the history of the Hawaiian Sovereignty movement. Then, I will explore the Hawaiian language itself and the history of its revitalization. Finally, I will explore the initiatives of the current Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement, and how it supports language revitalization as well as how this language revitalization supports the sovereignty movement.

History of the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement

After its initial occupation by Great Britain, the Kingdom of Hawai‘i was internationally recognized through treaties with other nations such as the Anglo-Franco Proclamation with Great Britain and France in 1843 (Ioane, 2022). The Kingdom was also recognized as sovereign by the United States through the Treaty of Commerce, Friendship, and Navigation in 1826. Unfortunately, this treaty was not ratified by the United States Congress but was respected by both entities (Stauffer, 2018). Due to this lack of ratification, American interests who intended to annex the islands into the United States were able to promote their cause as Americans bought up land for sugar plantations (Meller & Lee, 1997).

The Bayonet Constitution of 1887 solidified the political interests of Americans as they forced King Kalākaua to sign the document, tying property ownership to voting rights, thus disenfranchising many Native Hawaiians (Ioane, 2022). Opposition to this document was consolidated into a political group called Hui Kalāi‘āina, which became the main political organizing group for Native Hawaiians at the time.

Subsequent action years later saw the coup d’état’of Queen Lili‘uokalani on January 17, 1893, by United States troops, creating the American Provisional Government. Native Hawaiians continued to resist this encroachment on their sovereignty, forming a group called Hui Aloha ‘Āina, which in collaboration with Hui Kalāi‘āina actively organized to combat the plans of the Provisional Government to annex Hawai‘i into the United States as a territory (Silva 2004).

This struggle continued in the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands through the Newlands Resolution in 1898. Native Hawaiians banded together, signed petitions, and even sent delegations to the United States to avoid the annexation of the islands (Silva, 2004). Even though the annexation took place through the Newlands Resolution, it should be noted that this was conducted through a joint resolution that only needed a majority vote as opposed to treaties that required a two-thirds majority. Furthermore, Native Hawaiians were not considered in this discourse, only the American Provisional Government that sought to control the islands. Years later when Hawai‘i was given the option for statehood, the choice was between continued status as a territory, or becoming a state of the United States, with no option for independence (Anaya & Williams, 2015).

During the 1960s and 1970s, there was a Hawaiian cultural revival that was followed by political activism modeled after other Civil Rights movements at the time on the mainland and taking inspiration from the Occupation of Alcatraz of Native American groups (Meller & Lee, 1997). The victory came in the ceasing of bombing the island of Kaho‘olawe, and the island becoming a land base for the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement as it was to be placed under the control of a “sovereign native Hawaiian entity upon its recognition by the by the United States and the State of Hawai‘i” in 1981 (Meller & Lee, 1997, p. 173).

A core ideology of the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement is the concept of aloha ‘āina: loving the land. This concept was created in Native Hawaiian newspapers in circulation during the anti-annexation struggles of 1893-1900 (Silva, 2004). These newspapers, written in the Hawaiian language, promoted political views of resistance and contained stories from oral traditions, chants, and genealogies. Aloha ‘āina is based on ancient cosmologies that tie the land, the taro (an important plant for consumption), and the people into the same family that have the responsibility to care for one another (Silva, 2004). This concept has evolved to today’s Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement to be characterized by wahi pana aloha ‘āina, or storied places of resistance (Ioane, 2022). The Native Hawaiian connection with the land is significant when discussing Hawaiian political sovereignty. By looking to place names and remembering the events that happened there and passing along this significance, Native Hawaiians can further signify their connections to the land. This also adds to colonial resistance as sovereignty is based on such relationships with land (Ioane, 2022).

The Hawaiian language is also vital to the Hawaiian political sovereignty movement. For example, the mele (songs, chants, poems, etc.) performed in the protest of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Maunakea in 2019, highlight a shift in the narratives of the protests insisting that indigenous science is science and intertwining Hawaiian cosmologies in referencing Maunakea as family, not a commodity to place a telescope upon (de Silva, 2022). The use of Hawaiian language in these protests allows for a connection of the movement with the ancestors of the past and to express Hawaiian concepts through a cultural lens.

Today, the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement is composed of many different groups, all advocating for their version of sovereignty. To some, political sovereignty calls for the full restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom, while to others it means forming a nation-to-nation relationship with the United States like what Native American groups on the mainland have with the United States government (Meller & Lee, 1997).

The Hawaiian Language

The Hawaiian language is a member of the Austronesian family. Some unique aspects of the language are the ʻokina (ʻ) and the kahakō (ō). The ʻokina denotes a glottal stop while the kahakō notates the lengthening of the pronunciation of the vowel it is stationed above (Romaine, 2002).

After the coup d’état’of Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1893, the American Provisional Government, headed by Sanford Dole, banned the use of Hawaiian in schools, and in 1894 made English the official language of education (Romaine, 2002). As time went on, English eventually became the language of business and government as well. Through the decades, the Hawaiian language began to lose its initial pronunciation and expression due to its loss in status and usage, as well as English influence. Even though there were many Hawaiian newspapers, championing the writing and reading of the language, the same cannot be said for the spoken language. Initially, when missionaries came to the islands in the early 1800s, their recordings of the language were not complete as they failed to detonate the glottal stop and vowel elongation as significant to the language (Romaine, 2002).

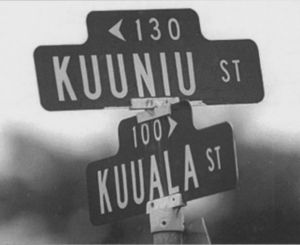

As such, this affected how words are pronounced, as words with similar or the same spellings, but have different phonological attributes are spoken the same. This results in contrasts between Hawaiian and local English pronunciations that include the omission of the glottal stop, shortening, and reduction of long vowels, omission of intervocalic /h/, and the merging of final /i/ and /e/ (as seen in the word Kamehameha, the ruling dynasty in Hawaii from 1795 to 1872, when /ka’meha’meha/ turns into /kə’meiə’maiə/), and the diaphanization of monophthongs (as seen in the word Kona, his, when /’kona/ turns into /’kouna/) to name a few (Romaine, 2002, p. 204).

Another example is how the glottal stop that is supposed to occur in the word ‘ono, meaning tasty, is often forgotten and merged to become ono, the name of a fish (Romaine, 2002). This also happens with place names when ʻokinas and kahakōs are omitted from spelling and pronunciation. Another prime example of this is the pronunciation of the word Hawai‘i. Many people do not acknowledge the glottal stop as well as the Hawaiian phonological attribute of the /w/ becoming a /v/ (Romaine, 2002, p. 202).

However, there are efforts championing signage and pronunciation that are consistent with Hawaiian phonology. There is also attention to this in the public sphere as major newspapers and national parks have begun to include ʻokinas and kahakōs on their signage (Romaine, 2002). This contested issue of the Hawaiian language in signage around the state continues to be a source of activism for those who want to see the Hawaiian language represented without English influence.

History of Hawaiian Language Revitalization

The revitalization of the Hawaiian language began in 1984 with the efforts of the non-profit ‘Aha Pūnana Leo by opening language immersion schools, following the “language nest” model. This is significant as by statehood in 1959, there were no Hawaiian-speaking children entering school on the islands, except for a small population on Ni‘ihau (Aguilera & LeCompte, 2007). Their strategy of the “language nest” was to ensure that language, culture, and traditions could be passed down to children through the participation of their families and the community in tandem with the school (Aguilera & LeCompte, 2007). In these schools, children learn in complete immersion in the Hawaiian language. As time has gone on, these schools have been given access to funding by the Department of Education, allowing for the investment of education in Hawaiian. Furthermore, as previously discussed, these schools have plenty of educational reading material through the vast Hawaiian newspaper collection of the 19th and 20th centuries (Aguilera & LeCompte, 2007).

Hawaiʻi is also unique as the majority of public signs on the islands carry Hawaiian place names (Romaine, 2002). However, even though the Hawaiian langiuage is highly visible on the islands, the meanings of the names on this signage are no longer vastly known (Romaine, 2002). Therefore, as the Hawaiian language has been revitalized, there is hope for increased understanding and advocacy for these types of signage to remain. Furthermore, Hawaiian chants and narratives are full of significant place names that have rich meanings and therefore can be fully understood with knowledge of the Hawaiian language (Romaine, 2002). Due to the integration of culture in the language nest schools, the upcoming generations of Native Hawaiians are being raised with the cultural values and language of their ancestors which provides them with an increased understanding of the cause of Hawaiian sovereignty advocates.

Support for Hawaiian revitalization has also crossed into public policy as a bill signed by the governor of Hawaiʻi in 1992 allowed ʻokinas and kahakōs in documents prepared by, or for the state (Romaine, 2002).

Conclusions

The concept of wahi pana aloha ‘āina that is becoming important in the current Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement is centered around the revitalization of the Hawaiian language and culture. To understand these storied places, one must be familiar with the culture and meanings of the place names, therefore understanding the Hawaiian language is vital.

Furthermore, the ties between advocation for Hawaiian Sovereignty and language revitalization are seen in the recent insurgence of people wanting Hawaiian to be spoken and written within its original context. Noenoe K. Silva refers to this as “anticolonial nationalism” (2004). This idea is applied to the Hawaiian case by Silva but was originally conceptualized by Partha Chatterjee who says this allows national culture to be maintained to where “the nation is already sovereign, even when the state is in the hands of the colonial power” (Chatterjee, 1993. p. 6). Therefore, this cultural revitalization that is important to the modern Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement persists to give life to its cause.

Without the knowledge of the Hawaiian language, it is hard to understand the Hawaiian chants, songs, and poems (often known as mele) that are used when Native Hawaiians gather in protest. As the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement incorporates a cultural point of view, its use of the Hawaiian language reflects that language is important in cases of sovereignty. This mutualistic relationship between the sovereignty movement and language revitalization serve to promote one another, strengthening their aims.

References

Aguilera D., & LeCompte M. D. (2007). Resiliency in native languages: The tale of three Indigenous communities’ experiences with language immersion. Journal of American Indian Education, 46(3), 11-36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24398541

Anaya, S. J., & Williams, R. A. (2015). Study on the international law and policy relating to the situation of the Native Hawaiian people. University of Arizona. https://law.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/Study%20on%20the%20International%20Law%20and%20Policy%20Relating%20to%20the%20Situation%20of%20the%20Native%20Hawaiian%20People.pdf

Campbell, L. (2010). Language isolates and their history, or, what’s weird, anyway? Berkley Linguistics Society, 36, 16-31. https://doi.org/10.3765/bls.v36i1.3900

Carnie, A. (1995). Modern Irish: A case study in language revival failure. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics, 28, 99-114.

Chatterjee, P. (1993). Whose imagined community? In S. B. Ortner, N. B. Dirks, & G. Eley (Eds.) The nation and its fragments: Colonial and postcolonial histories (4th ed., pp. 3–13). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvzgb88s.4

de Silva, K. (2022). Haʻu ka waha i ka nahele: Dissonance and song in Kanaka sites of counter-memory. Space and Culture, 25(2), 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/12063312211066547

Ioane, K. W. (2022). Wahi pana aloha ʻāina: Storied places of resistance as political intervention. Genealogy, 6(1), 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6010007

Meller, N., & Lee, A. F. (1997). Hawaiian sovereignty. Publius, 27(2), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a029904

Romaine, S. (2002). Signs of identity, signs of discord: Glottal goofs and the green grocer’s glottal in debates on Hawaiian orthography. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 12(2), 189-224. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43104013

Silva, N. K. (2004). I kū mau mau: How Kānaka Maoli tried to sustain national identity within the United States political system. American Studies, 45(3), 9-31.

Stauffer, Robert H. (1983). The Hawai’i-United States treaty of 1826. Hawaiian Journal of History, 17, 40-63.

I would like to thank everyone who helped me on my journey of writing and publishing this paper. First, I would like to thank the Patacsil family for inviting me on a trip to Hawai’i and sharing the culture of their family and the history of the islands that inspired this research. I would also like to thank my professors Dr. Michael Sullivan and Dr. Aaron Moreno for encouraging my interest in this topic and teaching me how to write an academic paper. Lastly, I would like to thank Dr. Meghann Peace for giving me this opportunity to share my research, as well as to look into the linguistic component of the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement.