August 1, 30 B.C.E.

Cleopatra, her women, and Mark Antony’s servants help to carefully raise Mark Antony to a window in Cleopatra’s mausoleum. As Antony lays in Cleopatra’s arms, bleeding from his stomach, he tells her “‘not to lament him for his last reverses, but to count him happy for the good things that had been his, since he had become the most illustrious of men, had won greatest power, and now had been not ignobly conquered, a Roman by a Roman.’” 1

Mark Antony was a Roman general who worked closely with Julius Caesar up until his assassination. Antony worked under Caesar during the Gallic Wars and in the civil war with Pompey, but the relationship deepened when they found out that they shared similar political views and ideologies regarding the power of the Senate. In 43 B.C.E., after Caesar’s assassination, Antony formed the Second Triumvirate with Octavian Caesar and Lepidus in order to consolidate power and avenge Caesar. If he was this great, how did he end up dying in the arms of the Egyptian queen not even two decades after his rise to power? To answer that we have to go back to 42 B.C.E., to the Battle of Philippi.

October 3, 42 B.C.E.

Mark Antony and Octavian Caesar’s forces close in on the main conspirators of Julius Caesar’s assassins, Gaius Cassius and Marcus Brutus. Octavian’s troops, in disarray, were captured by Brutus due to his military experience from his time under Pompey during Caesar’s civil war. His firsthand experience gave him an advantage due to Octavian’s inexperience. On the other side, Antony’s forces broke through Cassius’ defenses but had to retreat to aid Octavian after his defeat. Cassius, however, believed that his forces had lost the battle and been captured or killed, and he decided to commit suicide rather than join Brutus. 2

October 23, 42 B.C.E.

After weeks of planning, Brutus launched an attack that developed into a full-scale battle between both armies. The confined space between the marsh and mountain in Philippi, Greece limited the number of soldiers that could fight and the use of long-range weapons, causing the troops to have to fight from close quarters. Eventually, Brutus’ army retreated in an attempt to reorganize and regroup, but Antony’s army surrounded them. Brutus, following in Cassius’ footsteps, committed suicide, causing his men to surrender. 3

Finally, after months of chasing after them, the Second Triumvirate was able to avenge Caesar and regain control of Rome. After the battle, the Second Triumvirate focused on dividing Rome between themselves, eventually deciding on Mark Antony controlling the East, Octavian the West, and Lepidus Africa.

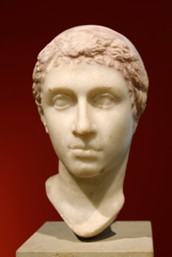

Mark Antony and Cleopatra first met when Antony called her to discuss her neutrality in the war between the Second Triumvirate and the assassins.4 This marked the beginning of their political relationship, which quickly turned romantic in the late summer after Antony accepted her demands. Although Cleopatra never gave Antony the money he wanted, she still found a way to make herself indispensable—giving him the hedonistic lifestyle he loved.5

However, that didn’t last for long. In early 40 B.C.E., Antony left Alexandria with a fleet of 200 ships after Labienus killed Antony’s governor, and he didn’t see Cleopatra again for almost four years. Antony hopped from place to place, city to city, to gather all of his troops to attack Parthia, until he found out about the state of the nation: the fall of Persia, Octavian’s power grab, and the rising threat of Sextus Pompey. He spent the next few years in Athens to settle his affairs with Octavian and Sextus, make a battle strategy, and extend his power over the east.6 With this also came his marriage to Octavia, Octavian’s sister. Antony had to leave behind his fling with Cleopatra and marry Octavia to keep the peace with Octavian. When Antony, who was deified as Dionysus in Asia and Athens and Osiris in Egypt, found out that his new wife was the Athena Polias, he demanded, and received, a dowry of 1000 talents from the city.7 This shows how this marriage was simply political, even economical in this sense. However, once he found a better deal, he quickly shifted his alliance back to Cleopatra.

Antony recognized that as he expanded his influence over the East, he would need more troops than even Octavian could offer. Following several personal and political correspondences with the mother of his twins, Antony gave Cleopatra the land grants she wanted and marriage. Marc Antony officially married Cleopatra according to Egyptian customs, which was not seen as valid in Rome, in 36 B.C.E., even though he was still technically married to Octavia. This caused the ties between Octavian and Antony to further fray, along with his relationship with the Roman people. 8

In 32 B.C.E., Octavian staged a coup and surrounded the Senate with an army to denounce Antony. The Senate was no match for Octavian’s army and was forced to cooperate. Antony’s two consuls, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Gaius Sosius, and 300 senators fled from Rome to join Antony in the East. Seeing that none of the remaining 700 senators refused his rule, whether by neutrality, indecision, or fear, Octavian named himself the representative of the republic; however, the consuls and the 300 senators in Alexandria denounced this and claimed themselves to be the true Senate.9

Even after his bigamous marriage with Cleopatra, Octavia remained by his side. While Antony flaunted his marriage with Cleopatra, Octavia stayed at his house in Rome and watched over his children: his two sons from his previous marriage and their two daughters. She was the buffer between Octavian and Antony’s discourses and what kept the two from bashing heads. Her exceptional virtue and how Antony was prancing around with Cleopatra, caused the Roman people to gain sympathy for her and further ruin their perception of Antony. Once Antony officially divorced her in the early summer of 32 B.C.E., she left his house in Rome and took all of his children, except for his eldest son. This was the deciding factor for some of the senators to stop supporting Antony and leave his side.10

Octavian judged the public’s opinion of Cleopatra and Antony and found that, while the public opinion of Cleopatra was sufficiently negative, their opinion of Antony was still too positive to turn the Roman people against him. In late 32 B.C.E., Octavian got the Senate to officially declare war on Cleopatra, but they were too scared to include Antony in this declaration.11 This, however, was simply a formality, considering they had been preparing for this for over a year. Octavian, unconstitutionally, pledged an oath to himself and had his army and other citizens pledge a common oath to himself. Roman citizens throughout Italy pledged their loyalty to him, town after town, regiment after regiment, swearing their allegiance to him.12 However, his Western support wasn’t completely unanimous. Antony had friends, clients, and even veterans throughout the West that remained loyal to him. Antony used those who still supported him to get more people to swear allegiance to him instead of Octavian.13

In the spring of 31 B.C.E., Antony and his troops traveled from Patrae to Actium, preparing for the most important battle in the entire war: the Battle of Actium. Antony’s strategy was to try to cut off Octavian’s attack and keep the supply lines open to Egypt. Antony stationed men along the coast of Greece, from Corcyra to Methone. This, along with Crete and Cyrenaica, captured the supply line to Egypt. While Antony had the advantage of knowing the land, Octavian had some critical advantages too, such as a larger military. While Antony had “19 legions of approximately 60,000 Italians, 15,000 light-armed Asiatics, plus 12,000 cavalry” and over 500 warships, Octavian on the other hand, had “a likely estimate [of] 75,000 legionnaires, 25,000 light-armed, 12,000 cavalry, [and] over 400 warships.” 14

Agrippa, Octavian’s general, led half of Octavian’s fleet to Methone, capturing it and breaking Antony’s supply line. Agrippa moved along the coast, securing critical positions along Antony’s supply line while Octavian immobilized Antony’s main army. Agrippa and Octavian easily limited Antony’s supplies to the impoverished Greece. This limited Antony’s supplies and made it so he only had meager weapons and supplies, not the more lavish and expensive weapons and supplies provided to Octavian’s army from Rome and other places.15

After this, Antony’s camp befell a myriad of issues: widespread diseases, food scarcity, and even debased currency. This, along with a “disastrously aborted” attempt to break the blockade, caused several of Antony’s men to switch sides and surrender to Octavian. Amyntas, king of Galatia, and Dellius, the courtier and historian who acted as a diplomatic agent between Antony and Cleopatra, were two who switched to Octavian’s side. However, Dellius’ betrayal was worse because, as a pledge to Octavian, he gave him a full account of Antony’s problems and plans.16

This became a common issue for Antony, leaving many legions and ships undermanned. He eventually had to set an example for some people caught fleeing by executing the king of Emesa and a Roman senator. However, the most painful betrayal was that of Domitius Ahenobarbus. Domitius, as mentioned previously, was Antony’s trusted counselor for years. He was even the one who ran from the Roman Senate to form a new one in Antony’s camp after Octavian took over the Senate. This was a huge betrayal since Domitius had been loyal to Antony for so long, yet he betrayed him and almost took the rest of the republicans with him.17

These betrayals, plus the significant loss of seamen, caused Antony to plan a sea retreat in order to minimize his losses. On September 2, 31 B.C.E., Antony started thinning out the weak ships in the center of his forces in order to give Cleopatra and her squadron the ability to maneuver out and flee back to Egypt with him following behind with the majority of his ships when able.18 This plan didn’t work out quite as planned, though. When it came time to actually follow through, Agrippa broke through Antony’s defenses, scattering his ships everywhere. By the time that Cleopatra and her squad could get out, Antony was only able to escape with about forty ships. The rest fought savagely for a while until they eventually surrendered to Octavian. At least fifteen ships and 5,000 of Antony’s men died.19

Cleopatra, sensing inevitable defeat, escaped to Alexandria. She took matters into her own hands and left with her treasure. She decorated her ships with victory garb, making it seem like they had won the battle. When she arrived, before the enemies could pull the veil off their eyes, she killed anyone she deemed dangerous to her and whose wealth was more valuable than their lives. While Antony was focused on the battle, she was focused on herself and her country. She knew that it was unlikely that Egypt would leave this war unscathed, so she started thinking of negotiating with Octavian.20

It wasn’t until Antony realized most of his loyal followers in Rome switched sides and began following Octavian, recognizing him as the true ruler of the Roman people, that he decided to flee to Alexandria with a small group. When they arrived at Alexandria, Cleopatra was feverishly preparing to defend her country, still believing that they could win. Antony, however, had no such hope of victory. He isolated himself in his Timonium for weeks before he completely gave up and left for the court and Cleopatra, choosing to stop wallowing in self-pity and live his hedonistic life again. He figured if he was going to die, he was going to live as much as possible first.21

August 1, 30 B.C.E.

Growing desperate, Antony did everything he could to minimize the damage. He offered Octavian a single combat between the two of them instead of a full-blown battle, but Octavian refused. Afterward, he sent Octavian a proposal to spare Cleopatra in exchange for his life, but Octavian refused again. In one last desperate attempt, Antony put together the last of his troops to attack Octavian, but they immediately joined Octavian without a second thought.22 Cleopatra escaped the siege by seeking refuge in her mausoleum with her ladies, causing a rumor of her death to spread, eventually reaching Antony. No one knows exactly how this rumor began — perhaps it was her choice to disappear, or she intentionally deceived him — but this rumor was Antony’s last straw. Thinking he had lost everything; Antony ordered his servant Eros to kill him. Eros, not able to betray his master, chose to kill himself instead. Antony, ashamed that his servant was able to kill himself with less fear than him, plunged his sword into his stomach. This wound, though mortal, was not instantaneous, so he was still alive when word came that Cleopatra was not dead, but hiding. He was transplanted onto a stretcher and brought to her mausoleum.23

Cleopatra, her women, and Mark Antony’s servants helped to carefully raise Mark Antony to a window in Cleopatra’s mausoleum. As Antony lays in Cleopatra’s arms, bleeding from his stomach, he told her “‘not to lament him for his last reverses, but to count him happy for the good things that had been his, since he had become the most illustrious of men, had won greatest power, and now had been not ignobly conquered, a Roman by a Roman.’” 24 Cleopatra followed him soon after.

With their queen dead, Octavian took control of Egypt and was crowned the ruler of Egypt.25 With this, along with Antony’s name being debauched throughout Rome, Octavian, beloved by the people, was able to convert the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire, becoming the first emperor of the Roman Empire.

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 226. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 126. ↵

- Rupert Matthews, “Battle of Philippi | Summary | Britannica,” Britannica, accessed December 8, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Philippi-Roman-history-42-BC. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 153. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 154. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 155. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 156. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 168. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 206. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 207. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 208. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 209. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 211. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 211. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 217. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 217. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 218. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 219. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 220. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 223. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 224. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 225. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 226. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 226. ↵

- Eleanor Goltz Huzar, Mark Antony: A Biography, First Edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 227. ↵