The year 1860 is remembered as one of the most significant years in the history of the United States. Abraham Lincoln was elected president by the newly formed Republican party after defeating three other candidates. This was significant because Lincoln was elected without winning a single Southern state. Lincoln opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories, and the Southern states did not like that. They were all in favor of slavery’s expansion. South Carolina became the first state to secede from the union after the election, and Confederate troops then attacked Fort Sumter in Charleson Harbor, marking the beginning of the American Civil War.1

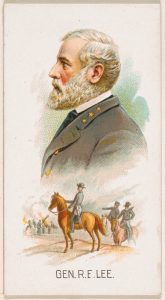

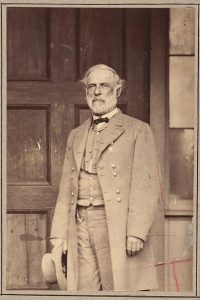

When we talk about the Civil War, some names and events come to mind, like Abraham Lincoln, and the Emancipation Proclamation, Ulysses S. Grant and his role as general, William T. Sherman and his March to the Sea. But there is one figure who many today remember as one of the “bad guys,” Robert E. Lee. He had been a distinguished officer in the U.S. Army, known for his strategic brilliance. Before the Civil War, Lee served with distinction in the Mexican-American War, in which he was recognized for his strong leadership skills. Lee was also described as a lovely father and person who was liked by everyone and everything by his son. Ultimately, the figure of Robert E. Lee was impeccable, deeply respected by his peers and superiors, a beloved husband, a good father, and a military genius. All these qualities made Lee one of the strongest candidates to lead the Union forces once the Civil War started, but he did not. Lee passed with an infamous prestige in history.2

To understand why Lee became one of the most skilled officials of the Union Army, it is crucial to review his success in military campaigns prior to the Civil War. During the Mexican-American War in 1846, Lee served as a staff officer under General Winfield Scott’s command. Lee was a key figure in Scott’s army, and he showed his value at the front in the battles of Cerro Gordo (April 1847), and Chapultepec (September 1847). In Cerro Gordo, Lee led Scott’s troops to find a way to surprise the Mexican forces who were led by General Santa Anna. Lee surprised the Mexican troops from behind, which was key to the victory, and was key to opening a path for the US troops towards Mexico City. Lee received a brevet promotion, which was an honorary promotion that recognizes bravery or merit, but doesn’t necessarily come with a corresponding increase in pay or rank in peacetime. It was a significant honor, particularly during that era.3

Once the war was over, Lee served in various positions, including as a superintendent at West Point Military Academy and as a cavalry officer. Lee was known for his dedication to his duties and his ability to train and discipline soldiers. He was respected by his peers and superiors and was considered one of the most talented officers in the U.S. Army. Lee served some time in Texas protecting the settlers from Native American indians. Lee’s time in Texas was marked by challenges, including harsh weather conditions, isolation, and the constant threat of conflict with Native American tribes. Despite these difficulties, he proved to be a capable and effective leader. His experience in Texas further increased his military skills and prepared him for the challenges he faced during the Civil War.4

One of the last acts Lee did as a Union colonel was to suppress the historically famous John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. John Brown, an abolitionist, led a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), with the goal of sparking a slave rebellion. However, the raid was unsuccessful, and Brown and his followers were captured by Lee and his troops. Despite being from the South, Lee did not let the wounded prisoners be lynched by the civilians and protected Brown and his men. “I have always observed,” he writes, “that wherever you find the negro, you see everything going down around him, and wherever you find the white man, you see everything around him improving.” And again: “In this enlightened age there are few, I believe, but will acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and a political evil in any country.”5 Even if Lee is now remembered for fighting in a war where slavery was one of the main reasons for it, he was a man of very strong morals and faithful to his ideals.6

Lee was a proud Virginian, a man of ideals who believed deeply in states’ rights. However, the Union government saw Lee as one of their most skilled and respected officers, and he was offered an important position in the Union Army. During the winter of 1861, Robert E. Lee, after the secession of Texas, was called to report immediately to General Scott, who was at the time the commander in chief of the United States of America’s army. Lee gathered his regiment and left from Fort Mason, Texas, to respond to the call of General Scott. At this time, the nation was already at war, and the states of the South were starting to secede. Lee was about to face one of the most important decisions of his life: who would he support during the American Civil War.7

For Robert E. Lee, the year of 1861 would define his story and his future role in the war. On March 1 of that year, he returned to Arlington, Virginia, to be with his family. Lee spent about two weeks when, on March 16, he was appointed colonel of the first cavalry for the Union Army, and called by General Scott to attend an important meeting with him. By April 18, General Scott offered him the command of the United States armies, but there was an inconvenience for Lee. Virginia seceded from the Union one day before the meeting with Scott.8

As a loyal Virginian, and being the descendent of a line of Virginian military officers, Robert E. Lee decided to resign from the Union Army on April 20th of 1861. Lee wrote to his superiors: “General: Since my interview with you on the 18th inst. I have felt that I ought no longer to retain my commission in the Army. I therefore tender my resignation, which I request you will recommend for acceptance. It would have been presented at once but for the struggle it has cost me to separate myself from a service to which I have devoted the best years of my life, and all the ability I possessed.”9 In his letter to his superiors, Lee also showed his deep affection to his friends in the Union, and expressed his desire for a more peaceful time. His resignation was signed that same day.10

Two days after his resignation, Lee was offered a position as the commander-in-chief of the Virginian Army in the growing Confederate States. Throughout the Civil War, Lee proved once again his military brilliance and his superb leadership. Robert E. Lee eventually became commander in chief of the armies of the Confederate States. In this position, Lee led the South to important victories in the battles of Fredricksburg (1862), the Second Battle of Bull Run, and Chancelorsville (1863). However, the South would eventually lose the war and the Confederate States had to surrender in the courthouse of Appomattox in April 1865.11

Robert Edward Lee passed to American history as a gray figure, his strategic mind, good leadership, and strong convictions are undeniable. As a Union soldier, Lee always showed loyalty and gained the trust and affection of both his peers and superiors. Lee’s decision to resign and join the South is proof of his loyalty to his homeland. His son wrote about him: “Everybody and everything–his family, his friends, his horse, and his dog–loves colonel Lee.”12

- Raymond Hylton and Raymond Pierre, “U.S. Civil War,” Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2023. ↵

- Captain Robert E. Lee, Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee, The Star Series (New York : SNOV, 2019). ↵

- Thomas Nelson Page, Robert E. Lee, Man and Soldier (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1911), https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcmassbookdig.roberteleemansol01page/. ↵

- Emory M. Thomas, Robert E. Lee : A Biography / by Emory M. Thomas (New York : W.W. Norton, 1995). ↵

- Thomas Nelson Page, Robert E. Lee, Man and Soldier (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1911), https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcmassbookdig.roberteleemansol01page/. ↵

- William Peterfield Trent, Robert E. Lee (Boston, Small, Maynard & company, 1907), http://archive.org/details/trentrobertelee00trenrich. ↵

- William Peterfield Trent, Robert E. Lee (Boston, Small, Maynard & company, 1907), http://archive.org/details/trentrobertelee00trenrich. ↵

- Captain Robert E. Lee, Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee, The Star Series (New York : SNOVA, 2019). ↵

- Captain Robert E. Lee, Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee, The Star Series (New York : SNOVA, 2019). ↵

- William Peterfield Trent, Robert E. Lee (Boston, Small, Maynard & company, 1907), http://archive.org/details/trentrobertelee00trenrich. ↵

- Thomas Nelson Page, Robert E. Lee, Man and Soldier (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1911), https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcmassbookdig.roberteleemansol01page/. ↵

- Captain Robert E. Lee, Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee, The Star Series (New York : SNOVA, 2019). ↵

2 comments

Danielle Villanueva

I learned a lot about Robert E. Lee’s early military career and the difficult choice he faced during the Civil War. The article showed how Lee was respected as a Union officer before deciding to fight for Virginia. I’m curious about how his perspective on slavery changed over time, and it would be interesting to see more details about his personal struggles with this decision.

Emilio Orona

This article/infographic is very balanced which is good since in history you always have to be in the middle and never take a side. Also, very scholarly research due to the inclusion of primary sources. Also, very limited but significant visual elements. For example, the portrait at the beginning and the coat at the end. Something I noticed was that the words were told like a tale rather than an article which made it very interesting. A con would be relying to much on military analysis rather than doing it for other topics like politics and his life.