Non-directiveness in Genetic Counseling

A rapidly developing field such as genetic counseling requires continuous ethical analyses of certain practices that affect patients. A rather controversial principle of genetic counseling involves that of non-directiveness. Non-directiveness is defined as giving patients “morally neutral” information about the genetic conditions and alternatives they may have.1 It is also regarded as a genetic counselor’s distance of oneself emotionally and morally, so as to prevent risk of giving recommendations based on their own values.2 Individuals seeking genetic counseling may have to make difficult decisions following a diagnosis, i.e. abortion, proactive (before cancer) or reactive (after cancer) surgery such as mastectomies, certain treatments and disclosure of genetic diagnosis to family members who may also be impacted.3 Non-directiveness, in and of itself, follows one of two models. There exists the more traditional decision-making model where professionals provide information as objectively or “neutral” as possible.4 There are also those that follow the counseling model, where client autonomy is encouraged, and informed decisions are made.5

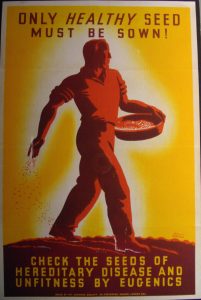

The term “non-directivity” was first coined by psychologist Carl Rogers in the early 1940’s6 and shortly thereafter adopted by the field of genetic counseling in 1974 by the American Society of Human Genetics.7 This was especially important after the events of World War II where eugenics was used as rationale for Nazi genocide.8 Though some counselors appeared to criticize non-directiveness as the standard of genetic counseling,9 this became an ethical cornerstone in the field in an effort to distance genetic counseling from eugenics.10

The importance of genetic testing and consultation is an imperative factor in how genetic counseling has grown since the 1970’s, when the field’s first master’s degree program in the United States was founded.11 As these types of services become more advanced and mainstream, it is crucial to discuss what possible ethical issues surround genetic risk services in underserved communities. More specifically, how a non-direct vs. direct approach by these genetic counselors may help or potentially exacerbate issues surrounding genetic testing in lower- and middle-income communities (LMICs).

While some professionals in the field believe a “non-direct” approach should be taken as a result of the circumstances surrounding people living in LMICs, others believe many in this community need a more direct form of counseling that allows these patients to receive professional opinions and recommendations depending on their situation. Non-directiveness fails to address the social and economic context with which the decision is being made.12 These factors are crucial for individuals in LMICs to consider, so it may be beneficial for direct recommendations that take into account, for example, whether resources to assist individuals affected by genetic disorders are insufficient.13 This research presents and examines arguments for and against this “non-direct” approach in genetic counseling, as well as the implications this ethical cornerstone of genetic counseling has on people living in LMICs.

Cognitive Bias, Directiveness, and Eugenics in Genetic Counseling

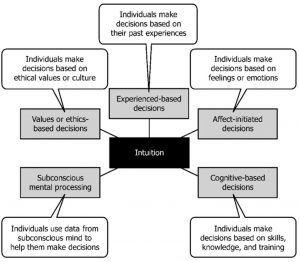

There are many that believe genetic counselors should not be too directive, as this may in turn allow for implicit or cognitive bias to slip through the cracks. Defined as societal attitudes or stereotypes that unconsciously affect our actions or decisions,14 implicit bias may in turn affect how genetic counselors influence the decisions of patients from LMICs. This is an ethical concern for many, as some clinicians in developing Eastern European and Asian countries have shown to have underlying eugenic attitudes in regards to the “goals” of genetics,15 as well as utilize directiveness to influence their patients’ decisions after prenatal diagnosis. When a genetic counselor includes financial status as support for termination of life, for example, this might be interpreted by some as eugenics.16

This is especially concerning when it comes to people in LMICs, who tend to prefer shared decision-making with professionals on issues like these.17 In a 2012 study conducted in Turkey (a moderately developed country at the time) 29% of the women said that if their fetus was diagnosed with Down syndrome following a prenatal screening, they would leave the decision to terminate the pregnancy up to the doctor.18 This introduces the potential for counselors to impose their own beliefs regarding caring for a child with Down syndrome onto the patient, which is why many believe non-directiveness should be implemented. This viewpoint argues genetic counselors have a responsibility to recognize their services have consequences that may affect people in LMICs psychosocially, and too much directiveness could lead to catastrophic ethical consequences such as eugenics.19

It is important to recognize the counselor can never live the life of the counselee, therefore presenting a framework of issues for them to consider but not necessarily leading the individual to make a certain decision for the patients is crucial.20 By directing patients towards certain decisions that may go against their own morals, distrust of genetic services in LMICs will only grow.

On the other hand, some view non-directiveness as counselors attempting to avoid and isolate genetic counseling from these difficult ethical issues altogether.21 These issues will always be integrated into this field so long as services like prenatal genetic testing and consultation are offered. Supporters of directiveness believe considerable thought must be given to what kind of hardships those in these communities may face in the wake of a diagnosis, and that this can only be achieved by taking into consideration a patient’s family dynamic, financial situation, and overall well-being of themselves and their children.22

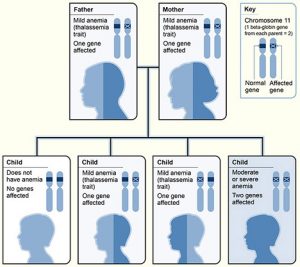

Risk for Misinterpretation of Genetic Information

As advancements in research surrounding genetic testing and disorders progress, the risk for misinterpretation of results by the average patient becomes more prevalent,23 especially in underserved communities. Research suggests knowledge of genetic services and diseases is correlated to socioeconomic status, as well as education.24 Those in support of genetic counseling implementing more of a directive approach argue counselors should be given broader license to make professional recommendations and keep patients as informed as possible about their diagnosis and its implications.25 Those opposing directiveness may argue that there are ethical concerns within this, as patients that are uninformed may not be open to learning about their diagnosis and will simply follow the counselor’s recommendation.18

Social Stigma Surrounding Genetic Disorder Diagnosis

An additional ethical consideration is the social stigma and stereotypes surrounding genetic disorders in LMICs. Disruption of family and religious values, for instance, may be at risk for these individuals.24 Prejudice against individuals considered “genetically inferior” affects how many people view genetic services and diagnosis.28 Patient studies suggest a diagnosis may cause an individual to become hesitant in disclosing this information to their family members for fear of judgement.29 Patient’s religion or spirituality may affect their decision-making process following a diagnosis and how they cope with this decision.30 Religious and familial relationships are unfortunately at risk following genetic diagnoses, especially in LMICs where social stigma around genetic disorders exists. These ethical concerns appear to suggest a more neutral stance by genetic counselors should be given to patients when it comes to decision-making, and that simply “prescribing a solution” for people in LMICs based on the counselor’s own beliefs is unethical.20

This can be especially problematic considering the lack of diversity in the field of genetic counseling, combined with the fact that up until recent years, most patients that seek out these services are from higher-income communities (HICs). This type of service is still not the most accessible, with most genetic counselors being white, young, and female,32 which can lead to cultural, social, and linguistic barriers between counselors and patients in LMICs. When this barrier exists, is it necessarily ethical for genetic counselors to influence patient decisions?

Are Non-directive Methods Practical?

Some experts in the field find non-directiveness to be non-feasible and impractical. For instance, how should a counselor respond to a question from a patient such as, ‘What would you do?’ An answer to this question could be thought by some to be “inherently directive”.33 The non-directiveness model also assumes that each person seeking counseling is free to make their own individual choices (i.e. assuming a woman’s male partner and family are supportive of her choice of abortion), and that patient autonomy is preserved. However, for some women, minority groups, and those in LMICs this is not a universal truth, therefore non-directiveness cannot be applied.16 Research has also shown that genetic risk is not often well understood following genetic testing and counseling, with one study reporting almost 43% of participants still having uncertainty about the meaning of genetics and cancer risk.35 This raises questions surrounding how effective non-directiveness in genetic counseling is.

Providing recommendations and advice for patients based on proactive, evidence-based professional opinions and the unique situations of each person seeking genetic counseling has shown to benefit patients. Motivational interviewing, a counseling method that is used to help elicit a patient’s motivation for change in habits that could prevent development or progression of certain genetic diseases, was used to encourage patients at risk for familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) to communicate with family members about the risks and undergo cholesterol screening.36 This resulted in proactive changes in behavior and increased positive cascade screening (patients sought cholesterol screening and communicated with family members about associated risks of FH).37

Research has shown many women receiving prenatal genetic testing (amniocentesis) prefer to have recommendations from a genetic counselor, as it helps alleviate the burden of decision-making for the individual, and they feel validated having a professional’s opinion.38 This supports the argument that individuals and families overall would benefit from receiving professional expertise in genetic risk assessment and decisions following genetic diagnosis.

Reflection on the Implications of Non-directiveness on LMICs

Upon engaging in the arguments supporting non-directiveness and those against it, it appears that those living in LMICs may require a more directive form of counseling. The arguments presented explaining why counselors should move away from non-directiveness appears beneficial to LMICs. As a result, shared decision-making should be a staple in the field of genetic counseling. Ultimately, both parties have essential roles in the process of making difficult decisions following a diagnosis. Counselors inform and advocate for patients’ health and overall wellbeing, while also having to delicately balance having respect for patients’ values and their self-determination, even if they may not always agree.39 Patient autonomy is preserved, while also ensuring the individual has weighed all of their options based on their own feelings, values, and concerns. Most of all, the patient is not left uninformed about anything regarding the next steps they can take.

It’s important to keep in mind that decisions made as a result of genetic diagnosis should not be given to patients as a sort of prepackaged solution.20 Each person seeking out genetic counseling comes with their own morals, values, and opinions that they may not necessarily share with their counselors or other patients. Some patients will be better at sifting through the information presented to them, but some, such as those in LMICs may be more vulnerable to allowing the decisions they make to be influenced by a genetic counselor.41 For this reason, “solutions” to a patient’s diagnosis should not be reduced to an algorithm, even if it may work for most patients. Instead, multiple factors surrounding a patient’s situation should be taken into consideration, especially when it comes to people living in LMICs.

Non-directive genetic counseling takes into consideration the client’s personal values, potential for eugenic mannerisms, and cognitive bias from the counselor that may influence patient decision making. For this reason, some may believe it is more ethical to leave decision-making completely to the patient, and refrain from soliciting advice or suggestions in this regard. Those in favor of a more directive approach argue this is neither an effective nor practical method. This argument suggests directiveness reduces the risk for misinterpretation of results and helps patients that prefer to have a professional’s recommendation regarding difficult decisions. In LMICs, where underserved individuals may be uninformed on the hardships that come from raising children with disabilities, or undergoing treatments for genetic disorders, examining these methods and what they imply will lead to decisions that serve the patient’s best interests.

- Louhiala, Pekka, and Veikko Launis. 2013. “Directive or Non-Directive Genetic Counselling – Cutting through the Surface.” The International Journal of Communication and Health, no. 2, 28–33. ↵

- Isailă, Oana-Maria. 2023. “Revisiting the Nondirective Principle of Genetic Counseling in Prenatal Screening.” In Clinical Ethics At the Crossroads of Genetic and Reproductive Technologies, 101–18. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-19045-2.00019-2. ↵

- Kelly, Kimberly M., Lee Ellington, Nancy Schoenberg, Thomas Jackson, Stephanie Dickinson, Kyle Porter, Howard Leventhal, and Michael Andrykowski. 2015. “Genetic Counseling Content: How Does It Impact Health Behavior?” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 38 (5): 766–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-014-9613-2. ↵

- Hsia, Edward. 1979. “The Genetic Counselor as Information Giver.” Genetic Counseling: Facts, Values, and Norms A.M. Capron:169–86. ↵

- Kessler, Seymour. 1997. “Psychological Aspects of Genetic Counseling. IX. Teaching and Counseling.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 6 (3): 287–95. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025676205440. ↵

- Yao, Lucy, and Rian Kabir. 2024. “Person-Centered Therapy (Rogerian Therapy).” In StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589708/. ↵

- Fraser, F. C. 1974. “Genetic Counseling.” American Journal of Human Genetics 26 (5): 636–59. ↵

- Caplan, Arthur. 1993. “Neutrality Is Not Morality: The Ethics of Genetic Counseling.” In Prescribing Our Future, 1st ed., 17. Routledge. ↵

- Yarborough, Mark, Joan A. Scott, and Linda K. Dixon. 1989. “The Role of Beneficence in Clinical Genetics: Non-Directive Counseling Reconsidered.” Theoretical Medicine 10 (2): 139–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00539879. ↵

- Resta, Robert G. 1997. “Eugenics and Nondirectiveness in Genetic Counseling.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 6 (2): 255–58. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025624505382. ↵

- Stern, Alexandra Minna. 2009. “A Quiet Revolution: The Birth of the Genetic Counselor at Sarah Lawrence College, 1969.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 18 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-008-9186-8. ↵

- Weil, Jon, Kelly Ormond, June Peters, Kathryn Peters, Barbara Bowles Biesecker, and Bonnie LeRoy. 2006. “The Relationship of Nondirectiveness to Genetic Counseling: Report of a Workshop at the 2003 NSGC Annual Education Conference.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 15 (2): 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-005-9008-1. ↵

- Harper, Peter S., and Angus J. Clarke. 1997. Genetics, Society and Clinical Practice. 1. publ. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publ. ↵

- Schnierle, Jeanette, Nicole Christian-Brathwaite, and Margee Louisias. 2019. “Implicit Bias: What Every Pediatrician Should Know About the Effect of Bias on Health and Future Directions.” Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 49 (2): 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2019.01.003. ↵

- Wertz, Dorothy C. 1998. “Eugenics Is Alive and Well: A Survey of Genetic Professionals around the World.” Science in Context 11 (3–4): 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0269889700003173. ↵

- Zuckerman, Shachar. 2021. “The Emergence of the ‘Genetic Counseling’ Profession as a Counteraction to Past Eugenic Concepts and Practices.” Bioethics 35 (6): 528–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12861. ↵

- Eales, Owen O., and Selma Smith. 2021. “Do Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Patients Prefer Shared Decision-Making?” South African Family Practice 63 (1). https://doi.org/10.4102/safp.v63i1.5293. ↵

- Yanikkerem, Emre, Semra Ay, Alev Y Çiftçi, Sema Ustgorul, and Asli Goker. 2013. “A Survey of the Awareness, Use and Attitudes of Women towards D Own Syndrome Screening.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 22 (11–12): 1748–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04333.x. ↵

- Clarke, Angus J., and Carina Wallgren-Pettersson. 2019. “Ethics in Genetic Counselling.” Journal of Community Genetics10 (1): 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-018-0371-7. ↵

- Gildersleeve, Matthew, and Andrew Crowden. 2020. “‘Now It’s Your Choice’: Nondirective Genetic Counseling, Other Minds, Place and Counselee Empowerment.” Agathos 11 (1): 317–55. ↵

- Weil, Jon. 2003. “Psychosocial Genetic Counseling in the Post‐Nondirective Era: A Point of View.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 12 (3): 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023234802124. ↵

- Wolff, Gerhard, and Christine Jung. 1995. “Nondirectiveness and Genetic Counseling.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 4 (1): 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01423845. ↵

- Farmer, Meagan B., Danielle C. Bonadies, Suzanne M. Mahon, Maria J. Baker, Sumedha M. Ghate, Christine Munro, Chinmayee B. Nagaraj, et al. 2019. “Errors in Genetic Testing: The Fourth Case Series.” The Cancer Journal 25 (4): 231–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/PPO.0000000000000391. ↵

- Zhong, Adrina, Benedict Darren, Bethina Loiseau, Li Qun Betty He, Trillium Chang, Jessica Hill, and Helen Dimaras. 2021. “Ethical, Social, and Cultural Issues Related to Clinical Genetic Testing and Counseling in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review.” Genetics in Medicine 23 (12): 2270–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0090-9. ↵

- Jamal, Leila, Will Schupmann, and Benjamin E. Berkman. 2020. “An Ethical Framework for Genetic Counseling in the Genomic Era.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 29 (5): 718–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1207. ↵

- Yanikkerem, Emre, Semra Ay, Alev Y Çiftçi, Sema Ustgorul, and Asli Goker. 2013. “A Survey of the Awareness, Use and Attitudes of Women towards D Own Syndrome Screening.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 22 (11–12): 1748–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04333.x. ↵

- Zhong, Adrina, Benedict Darren, Bethina Loiseau, Li Qun Betty He, Trillium Chang, Jessica Hill, and Helen Dimaras. 2021. “Ethical, Social, and Cultural Issues Related to Clinical Genetic Testing and Counseling in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review.” Genetics in Medicine 23 (12): 2270–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0090-9. ↵

- Correia, Patrícia Santana, Pedro Vitiello, Maria Helena Cabral de Almeida Cardoso, and Dafne Dain Gandelman Horovitz. 2013. “Conceptions on Genetics in a Group of College Students.” Journal of Community Genetics 4 (1): 115–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-012-0125-x. ↵

- Awwad, Rawan, Patricia McCarthy Veach, Dianne M. Bartels, and Bonnie S. LeRoy. 2008. “Culture and Acculturation Influences on Palestinian Perceptions of Prenatal Genetic Counseling.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 17 (1): 101–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-007-9131-2. ↵

- Bakur, Khadijah, Jumana Al-Aama, Zuhair Alhassnan, Helen Brooks, Tara Clancy, Saud Takroni, and Fiona Ulph. 2020. “Role of Religion/Spirituality in the Context of Genetic Counseling: Health Professionals’ Experiences in an Islamic Country.” Journal of Biochemical and Clinical Genetics, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.24911/JBCGenetics/183-1596638212. ↵

- Gildersleeve, Matthew, and Andrew Crowden. 2020. “‘Now It’s Your Choice’: Nondirective Genetic Counseling, Other Minds, Place and Counselee Empowerment.” Agathos 11 (1): 317–55. ↵

- Abacan, MaryAnn, Lamia Alsubaie, Kristine Barlow-Stewart, Beppy Caanen, Christophe Cordier, Eliza Courtney, Emeline Davoine, et al. 2019. “The Global State of the Genetic Counseling Profession.” European Journal of Human Genetics 27 (2): 183–97. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0252-x. ↵

- Wachbroit, Robert, and David Wasserman. 1995. “Clarifying the Goals of Nondirective Genetic Counseling.” Report from the Institute for Philosophy & Public Policy 15 (2–3): 1–6. ↵

- Zuckerman, Shachar. 2021. “The Emergence of the ‘Genetic Counseling’ Profession as a Counteraction to Past Eugenic Concepts and Practices.” Bioethics 35 (6): 528–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12861. ↵

- Peipins, Lucy A., Sabitha Dasari, Melissa Heim Viox, and Juan L. Rodriguez. 2024. “Information Needs Persist after Genetic Counseling and Testing for BRCA1/2 and Lynch Syndrome.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 208 (1): 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-024-07377-9. ↵

- Kruger, Valerie, Krista Redlinger‐Grosse, Scott T. Walters, Erin Ash, Deborah Cragun, Patricia McCarthy Veach, and Heather A. Zierhut. 2019. “Development of a Motivational Interviewing Genetic Counseling Intervention to Increase Cascade Cholesterol Screening in Families of Children with Familial Hypercholesterolemia.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 28 (5): 1059–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1145. ↵

- Winchester, Bridget, Deborah Cragun, Krista Redlinger‐Grosse, Scott T. Walters, Erin Ash, Emma Baldry, and Heather Zierhut. 2022. “Application of Motivational Interviewing Strategies with the Extended Parallel Process Model to Improve Risk Communication for Parents of Children with Familial Hypercholesterolemia.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 31 (4): 847–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1554. ↵

- Salema, Diane, Anne Townsend, and Jehannine Austin. 2019. “Patient Decision‐making and the Role of the Prenatal Genetic Counselor: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 28 (1): 155–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1049. ↵

- Brock, Dan W. 1991. “The Ideal of Shared Decision Making Between Physicians and Patients.” Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 1 (1): 28–47. https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.0.0084. ↵

- Gildersleeve, Matthew, and Andrew Crowden. 2020. “‘Now It’s Your Choice’: Nondirective Genetic Counseling, Other Minds, Place and Counselee Empowerment.” Agathos 11 (1): 317–55. ↵

- Rentmeester, Christy A. 2001. “Value Neutrality in Genetic Counseling: An Unattained Ideal.” Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 4 (1): 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009972728031. ↵

3 comments

Natalia De la garza

Thank you for sharing this infographic! It does a fantastic job explaining non-directiveness in genetic counseling, showing how counselors provide unbiased information to help patients make informed decisions. The visuals and clear language make complex ideas easy to understand. It’s a valuable resource for anyone interested in the ethical aspects of genetic counseling.

Alysia Cano

This thoughtful analysis highlights the delicate balance between respecting patient autonomy and providing essential guidance, particularly in LMICs where social and economic factors heavily influence decision-making. A shared decision-making approach, grounded in cultural competence and an understanding of the patient’s unique context, seems to be the most ethical and practical solution moving forward.

Danielle Villanueva

This article provides an insightful exploration of the ethical complexities surrounding non-directiveness in genetic counseling. I was particularly struck by the nuanced discussion of how different cultural and socioeconomic contexts impact decision-making. The piece effectively highlights the challenges of balancing patient autonomy with professional guidance, especially in lower- and middle-income countries. I’m curious about how genetic counselors are currently being trained to navigate these delicate ethical considerations.