South Africa, the southernmost country on the African continent, known for its great natural beauty, cultural diversity, and historical aspects that still impact the country to this day, presents compelling security challenges. The minority white population of settlers established apartheid policies in 1948 to retain control by enforcing extremely oppressive segregation laws. It resulted in an extremely divided country, creating in effect three nations: “one of whites (consisting of peoples primarily of British and Dutch), one of blacks ( consisting of such peoples of the northwestern desert, the Zulu herders of the eastern plateaus, and the Khoekhoe farmers of the southern Cape regions) and one of colored (mixed-race people).”1 Today, South Africa remains among the most developed and economically diverse nations on the African Continent, an interesting contrast that highlights the country’s current security challenges. South Africa sports the highest crime rate in 20 years, not a record any state would care to hold, since it focuses on the extreme level of societal violence exacerbating already deep-entrenched inequalities. The persistence of direct violence in everyday life means no area of its economy or politics is spared from being undermined by decades of structural poverty and institutional violence. Economically, the country has relied on the extraction sector, rooted in the separatist policies and foundations of its apartheid system, which have significantly contributed to growing disparities in society, even after attempted reforms. Political corruption remains rampant at all levels of government, weakening its democratic institutions and presenting additional challenges to law enforcement, state organizations, and understaffed local police forces. How has the legacy of apartheid shaped the mining sector, further entrenching current economic disparities in South Africa while obfuscating opportunities to address the growing income gap inequality? How did the mining industry linked to the apartheid regime foster direct violence inflicted by its law enforcement agencies, and has the lack of accountability for earlier human rights violations prevented meaningful reforms? Can we provide possible solutions to address all three levels of security issues while emphasizing the importance of a multi-faced and bottom-up approach?

Apartheid’s Legacy Still Mines South Africa’s Towns Today.

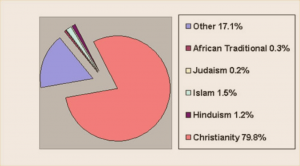

Understanding some of the most important cultural and social factors can help assess how the implications of the Apartheid system, so prevalent in the mining industry, have exacerbated structural poverty. South Africa took on its new flag and motto as the “Rainbow Nation” in 1994 to distance itself from Apartheid and highlight its rich cultural, ethnic, and racial diversity instead. “The Rainbow metaphor projects the image of different racial, ethnic, and cultural groups being united and living in harmony.”2It has thus become a symbol of unity among the diverse population of South Africa. The Rainbow represents a variety of cultures, languages, and traditions as well as reconciliation and unity. One of the reasons for this diversity in South Africa is the discovery of diamonds on the Witwatersrand in the 1860s; the country “experienced an influx of migrants seeking opportunities.”3 Since the dawn of its democratic transformation in 1994, many migrants all over the continent have moved to South Africa in search of economic opportunities. For some time, the country had a stable political system and a growing economy, which attracted people from other African countries. The country is the home of over 10 ethnic groups and with over 11 official languages. The 2022 South African census estimated the country’s population to be slightly over 62 million people, with Black Africans constituting 81.4%.4 The median age of the population rose to 28 years, a relatively young age when compared to other developed nations. The demographic profile includes over 55,000 individuals experiencing homelessness, predominantly males in metropolitan areas, due to factors like job losses and substance abuse.5 Religion is another major important factor in South Africa when it comes to shaping identity; the most predominant religious beliefs are Christianity, Islam, Animism -traditional African Religions, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism, among others. While diversity distinguishes South Africa, it remains the main cause for social injustice as one group received all conceded privileges over all others, as was the case with apartheid.

Even though the Apartheid Regime started in 1948, there were multiple early signs rooted in a long and violent colonial history, discriminatory colonial policies and legislation aimed at protecting white interests emerged in the late 1800s and early 1990s (Kriel 2007, 21). Soon after the formation of the Union of South Africa by the British in 1910, one of the most profound policies emerged, which was the Native Land Act of 1913, “which legalized segregation in the countryside and prohibited Africans from buying land.”6 Additionally, the National Party showed many signs of segregationist measures during the 1940s that focused on restricting and segregating Africans from everything involving political influence, where black Africans were denied representation. The scars of Apartheid run deep in South Africa, and they still shape many of today’s security issues in the country. The regime that lasted nearly 46 years took every measure to establish lasting cultural and structural violent institutions to undermine black Africans while ensuring the white minority remained privileged, even if only economically now.

These injustices expose an economic system filled with inequalities and disparities, and they become even more visible in the mining sector, one of the biggest industrial segments of its economy in the country. With its origin in colonialism, “the first mining operations took place in Namaqualand in 1852 and were followed by the discovery of diamonds in Kimberley in 1870.”7 In these mines, black male mineworkers were held in a facility with limited transportation and interaction with the surrounding communities. The labor model was based on groups of “black manual laborers overseen by a coterie of white supervisors”, which facilitated the ideological particularities of the apartheid regime in the industry.8 From the time that the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910, throughout the Apartheid era until 1979, labor laws were based on color distinction. In the case of the mines, the 1911 Mines and Works Act promoted segregation in employment. The life of a black mineworker was intended as a daily struggle for survivors as the owners paid sub-poverty wages to blacks, to keep them perpetually indebted and docile. As mentioned by Maseko, “it is difficult to fully understand the predicament of black mineworkers today without delving deeper into historical, discursive and structural processes unleashed by Euro-North American-Centric modernity on those epistemic sites, such as Africa.”9 Under this concept, the category of mineworkers emerged as a market-defined identity. In the post-apartheid era, mining has been resistant to broader processes of decolonization and democratization. “The mining industry in South Africa today resists changes by co-opting black people into the mining industry, but they never get promoted to influential positions that will allow them to initiate change”.10 Black Africans still struggle to have any sort of control in the mining industry and still operate following a segregated template, subjugated socially, economically, and politically through the specific form of proletarianization that took place historically in South Africa.

Many communities in South Africa depend on the mining industry to survive, however, economic instability in the mining sector has led to new challenges, and the industry has recently faced major retrenchments. Natural resources in abundance can, over time, reduce local economic growth and foster dependence. The government has opted for opening towns and the integration of mining into their local economy. This industry has become much more than just a source of income; it has built cities, communities, and economies, and provided food for over a thousand employees and their families. In addition, informal settlements burgeoned around mining towns where employment remains directly dependent on mining. Such exclusive industry integration increases the risk associated with global resource price fluctuation and becomes decimated whenever a mine closes. Small business operators seldom see these risks.”11 The link between mining and local communities has increased the local participation in their economies; however, they also increase their dependency on the industry, which remains volatile and dependent on global demand for resources. Furthermore, in economies like these, mining companies do not reinvest revenue from resources in education, employment, health, and the common good. Instead, they are used to continue the growth of the industry, maintain the rich owners and stockholders richer, while the poor die poorer. Lastly, economies over reliant on resource exploitation provide at best weak economic growth, at worst they decay weak political or democratic institutions, support high levels of corruption through dysfunctional state behavior that increases inequality, creates conflict, and social disruption.12

The impact of the recent closure of some of the biggest mines in the industry has impacted communities on many levels. The stories of the Blyvooruitzicht and Durban Deep mining communities “offer a damning portrait of the systemic marginalization the many communities, having grown up around major mining communities experience in the aftermath of the improper closure of those operations.”13 In the case of Durban Deep, years of side-stepping mine closure procedures have resulted in devastating consequences, which is the case for Boitumelo and her family. After the closure in 2010, she and her partner were forced to move from their home to an abandoned mine hostel as they were no longer able to afford rent. The government, however, stopped assisting these communities, leaving hostels in a deplorable situation. Today, Boitumelo has no access to clean water and electricity, and her life is a daily struggle to survive. The lack of access to sanitation compromises their dignity and raises concerns about public health. Additionally, she argued that the lack of services has led to increased crime rates, as the streets are darker and police have become unresponsive. In her own words, “It is hard to believe that this is our life now”. The closure of the Blyvooruitzicht Mine in Johannesburg has also left communities in a sad reality. “Situated in Carletonville, Gauteng, the Blyvooruitzicht Gold Mining Village is today home to some 6,000 people, historically comprised of mine workers and their families who today exist, unemployed, on the edge of the defunct.”14 The village grew up around this operation, and its members had a comfortable lifestyle; the mine paid for education, rent, water, and other resources. Its closure took everything away, and families were left without any support. For Martin, the right to equality entrenched in the constitution must be interpreted as a response to the oppression of the apartheid regime, which promoted the socio-economic development of the white portion of the population, at the price of the exclusion of marginalized groups and communities.

As these stories tell us, the mining industry was deeply intertwined with the apartheid regime, fostering direct violence through its collaboration with law enforcement agencies. This partnership is evident in the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre, where police opened fire on peaceful anti-apartheid protesters. “Official figures counted 69 dead and about 50 wounded, though further analysis has raised the human toll to at least 200 wounded, “mowed down” by police who fired into a crowd of about 4,000 unarmed protesters.”15 This event shows how the police used force to suppress any groups that defied the system, often in defense of economic interests tied to industries like mining. This pattern remains years after the end of apartheid, the Marikana massacre in 2012 is one example, “the police, acting on an unlawful decision, used unjustified lethal force against the miners, leaving 34 dead and more than 70 others injured”. Additionally, the police, possibly with the cooperation of other legal systems, also falsified evidence and attempted to mislead the judicial Commission of Inquiry into the deaths. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a governmental body that aims to address past human rights violations, lacked the authority to enforce reparations or legal consequences. This allows many perpetrators from the mining sector to evade justice, leaving the country with a vacuum of accountability and hindering any attempt to reform the industry. Currently, communities affected by mining activists across South Africa are exercising their human rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly to advocate for the government and private sector to respect and protect community members’ rights. In many cases, such activism has been met with harassment, intimidation, or violence. The Police are trained to use brutal force to disperse any activism, including shooting rubber bullets, using pepper spray, and causing extensive property damage. People who suffer from these acts tend not to report because they fear retaliation from the person making the threat or that the police will not take the allegations seriously. The threats to personal security, police and private security violence, and other conduct against community rights defenders have created an environment of fear, in which people are scared to advocate for their rights, and injustices are perpetuated in mining-dependent communities.

The mining industry in South Africa needs to be understood in the context of coloniality, “as it continues to function on an apartheid template, with race in large part structuring social relationships and social status on the mines”.16 Addressing security issues rooted in the country’s apartheid-era mining industry presents complex layers that require a multifaceted and bottom-up approach. The lack of accountability within law enforcement agencies enables the mine owners and private sector leaders to treat black mineworkers as unworthy and silence their voices, as if workers’ thoughts lack rationality and reasonableness. A solution demands a strong truth and justice process with accountability, including revisiting unresolved cases from the apartheid. The state must be held responsible when no action is taken when the private sector interferes with the full realization and enjoyment of these rights. Additionally, the government must adopt the “right legislation to protect human rights, the state must ensure the wrongdoer is sanctioned and the harm remedied”. 17 In failing to do so, international institutions must step in and acknowledge it as responsible for the harm inflicted by the private sector.

Second, economic disparities must be addressed by inclusive development. Legislation should require mining companies to reinvest in local communities, including housing, education, and healthcare. Furthermore, the state should strengthen regulations that ensure corporate accountability while incentivizing development in other sectors of the economy by supporting community-owned enterprises. In the long term, these steps will ensure economic empowerment beyond extractive industries and break cycles of dependency and poverty. Lastly, to address direct violence created by the mining industry, reform in the police system is crucial, ensuring accountability mechanisms and involving independent oversight bodies with the authority to prosecute. Community forums must be created, and restorative justice practices rooted in local traditions should be promoted to decrease the gap between the community and law enforcement agencies. Supporting initiatives like the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, that demonstrate how “a multi-disciplinary institute […] seeks to understand and prevent violence, heal its effects and build sustainable peace at the community, national and regional levels” displays a reproduceable blue print for impactful solutions.18 To be effective, these solutions must involve representatives and leaders from the public, local, and private sectors, ensuring that all levels are being addressed and heard.

Under all three securities issues, a bottom-up approach will be essential to ensure changes are shaped by those most affected. The local community should play a big role in the decision-making and implementation of new policies. The mining sector and the Government of South Africa point out that mining remains essential for economic development, but they fail to acknowledge that mining comes at a high social cost, and often takes place without adequate consultation with, or lacking the consent of, local communities. This industry can only become a force for security and equity in post-apartheid South Africa through participatory governance, social justice, and accountability mechanisms.

- Nel, A., Thompson, L.M., Bundy, C.J., Vigne, R., Hall, M., Lowe, C.C., Mabin, A.S., Cobbing, J.R., Gordon, D.F. (2025, April 11), South Africa, Encyclopedia Britannica. ↵

- Elirea Bornman, National symbols and nation-building in the post-apartheid South Africa, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Volume 30, Issue 3, 2006, Pages 383-399, ISSN 0147-1767, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.09.005. ↵

- Chikohomero, R. (2023). Understanding conflict between locals and migrants in SA: Case studies in Atteridgeville and Diepsloot. Institute for Security Studies. ↵

- People of South Africa | South African Government. (n.d.).People of South Africa | South African Government. (n.d.). https://www.gov.za/about-sa/south-africas-people. ↵

- People of South Africa | South African Government. (n.d.).People of South Africa | South African Government. (n.d.). https://www.gov.za/about-sa/south-africas-people. ↵

- Kriel, H. (2007). Conflict Transformation in South Africa: The Impact of the Truth & Reconciliation Commission on Social Identity Transformation. University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. ↵

- MASEKO, R. (2021). BEING A MINEWORKER IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA: A DECOLONIAL PERSPECTIVE. In M. STEYN & W. MPOFU (Eds.), Decolonising the Human: Reflections from Africa on difference and oppression (pp. 109–129). Wits University Press. ↵

- MARTIN, J., BRAVO, K. E., & VAN HO, T. (Eds.). (2020). When Business Harms Human Rights: Affected Communities that Are Dying to Be Heard. Anthem Press. ↵

- MASEKO, R. (2021). BEING A MINEWORKER IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA: A DECOLONIAL PERSPECTIVE. In M. STEYN & W. MPOFU (Eds.), Decolonizing the Human: Reflections from Africa on difference and oppression (pp. 109–129), Wits University Press. ↵

- van Rooyen, D., & van Zyl, J. (2022), Boom or Bust for Emalahleni Businesses? In D. van Rooyen, L. Marais, P. Burger, M. Campbell, & S. P. Denoon-Stevens (Eds.), Coal and Energy in South Africa: Considering a Just Transition (pp. 150–159), Edinburgh University Press. ↵

- van Rooyen, D., & van Zyl, J. (2022). Boom or Bust for Emalahleni Businesses? In D. van Rooyen, L. Marais, P. Burger, M. Campbell, & S. P. Denoon-Stevens (Eds.), Coal and Energy in South Africa: Considering a Just Transition (pp. 150–159), Edinburgh University Press. ↵

- van der Watt, P., & Matebesi, S. (2022). ‘The mines must fix the potholes’: A Desperate Community. In L. Marais, P. Burger, M. Campbell, S. P. Denoon-Stevens, & D. van Rooyen (Eds.), Coal and Energy in South Africa: Considering a Just Transition (pp. 205–217), Edinburgh University Press. ↵

- MARTIN, J., BRAVO, K. E., & VAN HO, T. (Eds.). (2020), When Business Harms Human Rights: Affected Communities that Are Dying to Be Heard. Anthem Press. ↵

- MARTIN, J., BRAVO, K. E., & VAN HO, T. (Eds.), (2020), When Business Harms Human Rights: Affected Communities that Are Dying to Be Heard. Anthem Press. ↵

- The Sharpeville Massacre, 1960 · Exhibit · Divestment for Humanity: the Anti-Apartheid Movement at the University of Michigan. (n.d.). ↵

- MASEKO, R. (2021), BEING A MINEWORKER IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA: A DECOLONIAL PERSPECTIVE. In M. STEYN & W. MPOFU (Eds.), Decolonising the Human: Reflections from Africa on difference and oppression (pp. 109–129), Wits University Press. ↵

- MARTIN, J., BRAVO, K. E., & VAN HO, T. (Eds.), (2020), When Business Harms Human Rights: Affected Communities that Are Dying to Be Heard. Anthem Press. ↵

- CSVR. (2025, April 25). CSVR | The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. https://www.csvr.org.za/. ↵

1 comment

Kamilah Rodriguez

Very interesting, I recall reading a biography that tells the story of a man’s childhood in South Africa. It mentions how he and his mother lived during the time of apartheid, showing a more personal experience. But this article dives deeper and has informed me of how far the injustice truly went, exposing the lengths which the government and corporations went to when taking advantage of these miners and their families.