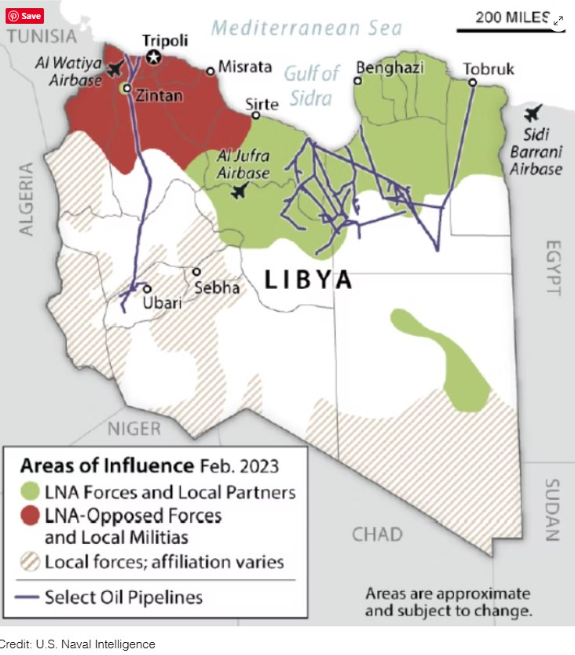

Libya’s map by US Naval Intelligence above reports on the de facto division in February 2023, between areas the the GNS/LNA in Green control and the areas the GNU controls in Red Intelligence

2025 Libya?

The North African nation of Libya, a vast expanse of territory, presents a stark paradox. Imagine a land larger than any European nation except Russia. It is a potential giant even if smaller than its neighbor Algeria and the home to a mere 7.3 million souls, a population smaller than New York City. If it were part of the United States, it would be the largest state in the union, slightly larger than Alaska and easily dwarfing Texas. Yet, in contrast to its size, its population is very small like that of Tennessee. This demographic contrast, augments with the concentration of nearly 90% of its 7.3 million people living along the Mediterranean coast. This leaves the heart of the country as a sparsely populated void, an empty expanse where authority frays and instability breeds. 1

Libya’s population is even smaller than its African neighbor, Tunisia, that only makes up one-tenth of Libya’s territory. Populations concentrates 80 percent of the its people–in 3 major metropolitan areas: Tripoli, Misrata, and Benghazi. Like its neighbors in North Africa, the population identifies as predominantly Muslim and officially Arabic-speaking, with a minority of Amazigh people (also known as Berbers). Nearly one-third of Libyans are 14 years old or younger, with fewer than five percent older than 65.2

Libya’s demographics have plagued the country’s political situation since uprisings in 2011 that since led to two civil wars and left the country divided between two major factions. The roots of Libya’s current instability sprang directly from the Arab Spring. While the 2011 uprisings brought exciting opportunities for democratization to neighboring Egypt and Tunisia, they marked a very serious shift towards a downward spiral for Libya’s security.3 Muammar Gaddafi’s violent repression of mass protests sparked a devastating civil war that led to his overthrow–with eventual American and NATO intervention–followed by the collapse of central authority and a renewed civil war only a few years later. Why have security challenges worsened over time in Libya since the fall of Gaddafi?

Libya finds itself in a precarious situation, beset by a storm of security challenges rooted in part by a de facto East-West division between its two major factions: The Government of National Unity (GNU) in the west, and the Government of National Stability (GNS) in the east, which is led and controlled by General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA). Each side is supported, to varying extents, by different foreign powers. The GNU receives support from Qatar and Turkey, while the GNS and LNA are supported by Egypt, Israeli arms and training, and Russia, which provides military support from the Putin regime’s Wagner private military company (PMC).4

| In the West of Libya | In the East of Libya |

| The Government of National Unity (GNU) receives support from Qatar and Turkey | Government of National Stability (GNS) and Libyan National Army (LNA) are supported by Egypt, Israel, with arms and training, and Russia, who provides military support from the Putin’s Wagner private military company (PMC) |

While there has been a ceasefire among the country’s two main factions since 2020, this situation is fragile and has not prevented periodic outbreaks of violence. In addition to violent and deadly clashes, the aftermath of Libya’s civil war has created a dangerous variety of security challenges, running the gamut from exploitation and human trafficking for migrants passing through the country, religious persecution in both GNS and GNU-controlled areas, and clashes between various factions in the country’s south, where the GNU and GNS both have limited reach. Unsurprisingly, Libya’s economy, particularly its oil industry, has been heavily affected by these challenges.5

Before going in-depth on Libya’s current security challenges (and how these might be addressed), this article will go over Libya’s history–albeit very briefly for its pre-2011 era–before arriving at its present moment. In order to provide a historical context, a brief overview of Libya’s colonial history to its 1951 independence and brief coverage of the Gaddafi era will be covered. It will then go somewhat more in-depth into the 2011 Arab Spring Uprisings that led directly to Libya’s civil war. A summary of the domestic situation at the beginning of that year and how it contributed to the uprisings’ spread into Libya will also be included, followed by the Gaddafi regime’s response to the protests, leading directly to civil war and eventual U.S. and NATO intervention. Gaddafi’s death and his regime’s collapse eventually led to the resumption of civil war in 2014. Lasting until an inconclusive ceasefire in 2020, this has left Libya in a precarious situation, marred with instability, de facto division, and the ever-present threat of renewed civil war.

There are a few key questions this writing seeks to address: What factors prevent Libya’s conflicting factions from forming a truly unified state? Does the international community have a unified approach towards Libya’s crisis? If not, is such an approach feasible? To begin with, understanding how Libya reached its current situation requires a knowledge of its recent history, particularly since 2011. While it is helpful to understand the country’s colonial history and the Gaddafi era, an in-depth discussion of both are outside of this article’s scope, therefore Libya’s pre-2011 history will only be discussed briefly. The most essential historical context concerns the impact of the 2011 Arab Spring Uprisings and Libya’s civil wars that resulted from them.

The Arab Spring, and Civil War, comes to Libya

Much like Libya’s social and economic conditions were ripe for instability, the Arab Spring Uprisings that engulfed the MENA region in 2011 were also rooted in oppressive regimes that failed to meet their people’s basic needs. The Arab Spring may have caught much of the outside world by surprise, but massive uprisings against the established order in the MENA region were not entirely unforeseen by those living in the region. The MENA region faced a tinderbox situation that, as events would prove, only needed a spark to ignite revolution throughout the Arab World. This spark was provided by the self-immolation of a Tunisian merchant, Mohamed Bouazizi, who was fed up with the Tunisian government’s repressive policies and the lack of economic opportunities. The mass protests that followed overthrew Tunisia’s long-ruling dictator, Zine el Abidine Ben Ali,6 and spread to the wider region, with similar results in Egypt, where the uprisings brought down the long-ruling dictator Hosni Mubarak’s regime. While these uprisings were far from bloodless–over 800 Egyptians died in the 2011 uprising7–they were far less violent than the tragic escalation into civil war that would engulf Libya and other Arab states.

Libyans witnessed the successful overthrow of Ben Ali and Mubarak in real time. In Libya, the spark of revolution was provided by the arrest of Fethi Tarbel, a human rights activist who focused on the persecution of political prisoners under Gaddafi. Protests calling for Gaddafi’s resignation erupted in mid-February 2011.8 It took less than two weeks for Gaddafi’s forces to use lethal force against anti-regime protesters, followed by a meeting of “high profile individuals” led by the country’s former Justice Minister to form the National Transitional Council (NTC) and declare themselves Libya’s official government.9 The uprising saw early successes, taking over large sections of cities such as Misrata and Benghazi. But this early success led to a renewed desire on Gaddafi’s part to use any means necessary to maintain his grip on power, resorting to lethal force and mass shootings of demonstrators, which led to calls in the U.S. and its allies to intervene militarily to stop atrocities.10

The “First” Civil War, US-NATO Intervention, and Gaddafi’s Defeat

Despite the hopeful beginnings of the uprisings, Gaddafi’s resort to violent reprisals against protesters quickly escalated into a full-blown civil war. While the NTC’s forces held some of the country’s major urban centers, their relatively uncoordinated resistance and lightly-armed forces faced severe early difficulties against the regime’s forces. Gaddafi’s loyalists began operations to retake rebel-held cities, and looked poised to retake Benghazi by late March. In response to a UN Security Council (UNSC) resolution that same month authorizing protection of Libyan civilians and a no-fly zone, military forces from the U.S. and various NATO countries began air strikes against Gaddafi’s forces in support of the rebels.

A planned Gaddafi offensive to retake Benghazi reached the city’s outskirts but was stopped in its tracks by NATO air power.11 While the outcome was far from immediate–the campaign would last several months–this was the conflict’s turning point. The sustained NATO campaign led to the gradual expansion of rebel footholds throughout the country. Tripoli had fallen to anti-Gaddafi forces by late August, leading the rebels to form a transitional government in September. Although he escaped the fall of Tripoli, Gaddafi himself was captured and executed by rebels in late October.12

The Resumption of Civil War

2011 was a violent and devastating year for Libya, especially in comparison to neighboring Tunisia and Egypt. However, Gaddafi’s defeat that fall provided a brief glimmer of hope that the country could move past its authoritarian past towards a more democratic future. Following Gaddafi’s death, the NTC sought to create a constitution. This Constitutional Drafting Assembly (CDA) quickly ran into difficulties, however. First, popular resentment resulted in mass protests against the NTC’s attempt to control who was part of the CDA, forcing the NTC to allow Libyans to vote on representatives who would help write the new constitution. Then, elections held in the summer of 2012 saw numerous incidents of violence which forced the closure of multiple voting centers. Violent incidents ranging from the attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi in September 2012, to further violence and violent threats preceding elections in 2014 led to a resumption of armed conflict.13

This outbreak of violence was facilitated by the fact that Libyans were unable to form a unified security force or military after 2011, a legacy of Gaddafi’s refusal to create a strong, unified military capable of exercising its authority throughout the entire country.14 Compounding this situation is that the U.S. and its NATO allies largely lost interest after Gaddafi’s defeat. The U.S. had achieved a reduction in violence in Iraq by 2011 while launching a surge in Afghanistan, and countries such as the UK and France saw an uptick in domestic political difficulties, leading to the deprioritization of Libya’s future. Whereas the U.S. invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan saw occupations, however poorly-planned and ad hoc, the west’s approach to post-Gaddafi Libya can be rightly characterized as leaving Libyans “to fend for themselves” while a variety of armed groups raided weapons and ammo sites.15

The resulting power vacuum created by Gaddafi’s death created a perfect storm of instability: Former Gaddafi regime officials were banned from holding office, people who had participated in the revolution felt like they were cut out of the new power structure, and the country lacked a strong government and civil service structure able to help manage disagreements among its members.16 The resulting power vacuum was filled by a competing mish-mash of “Islamist political groups,” armed militias and tribal groups. Combined with the laws banning former Gaddafi officials from serving in the new government, the resulting situation led to the rise of the Libyan National Army (LNA), led by former Gaddafi-era General Khalifa Haftar, who took control of Libya’s populous eastern territories. Scholar Farah Rasmi characterized Haftar’s campaign as helping to turn the Libyan conflict into an “east-versus-west contest” with control of the south depending on local tribes and their alignment.17

The resumption of conflict led to the establishment in 2016 of the Government of National Accord (GNA), recognized and facilitated by the UN. Even with this government’s establishment, however, the GNA was only able to establish a sense of order and relative security with the help of militias in the capital, Tripoli. The mish-mash described previously was present within the competing camps in this period, as “fragmented militias” and fighting between the GNA and Haftar’s LNA displaced many Libyans and killed thousands and creating a “fertile ground for proxy wars” with various armed groups switching sides, often unpredictably. Many foreign actors became involved, supporting different armed groups and creating a black market for arms sales and trafficking within the country. A failed attack by Haftar on Tripoli in 2019 helped strengthen Islamist groups in Tripoli.18

ISIS in Libya – A Microcosm of Libya’s Wider Problems

In the midst of the chaos and disunity of Libya’s “second” civil war, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) was able to establish a foothold in some of the country’s coastal regions, particularly cities such as Sirte. Although its influence and control was shorter-lived and less widespread than its Iraqi and Syrian counterparts, their rise and fall provides an insightful snapshot of how Libya’s chaotic internal divisions and conflicts fuel further conflict and grievances, ripe for exploitation. Azeem Ibrahim, writing in 2020 for the U.S. Army War College, describes how the post-Gaddafi splintering among Libya’s armed factions, combined with a pullback from the Western nations that helped overthrow Gaddafi, exacerbated the country’s problems. It led to a situation where various foreign and regional actors, with agendas as varied as Libya’s own internal factions, supported different sides.19

For example, the Egyptian regime of Abdel al-Sisi, having come to power after overthrowing a Muslim Brotherhood-led government in a coup, was determined to prevent the Brotherhood’s Libyan branch from establishing itself in power. Qatar, on the other hand, was primarily focused on gaining at least some control of the export of Libyan oil and gas. The Qatari government has also shown a “willingness and desire” to improve its relationship with Iran and has supported Muslim Brotherhood branches, something that has put them at odds with Saudi Arabia, who accused–albeit without independently-verified evidence–the Qataris of funding ISIS in Libya.20

While the process happened more quickly in Libya, ISIS followed a trajectory comparable to its Mesopotamian branch: It gained initial early success fueled by instability, division, and conflict. It overreached and put itself at odds with potential allies, and made enemies of most local armed groups that might otherwise have been willing to join its cause due to its insistence that all their goals be subordinated to the caliphate’s establishment. The end result was that most of Libya’s armed groups eventually fought ISIS before its defeat. Despite their shared loathing of the Islamic State and its ruthlessness, Libya’s factions turned out to be less concerned about defeating ISIS in and of itself. Ibrahim characterizes the defeat of ISIS as motivating Libya’s factions to gain glory and political influence by who could claim the most credit for its eventual defeat. For example, the elimination of ISIS’s main Libyan stronghold in Sirte in 2017 risked devolving into conflict between the then-Government of National Accord (GNA) and Haftar’s LNA, until GNA-connected forces secured the city first.21

While ISIS was defeated in Libya, its ability to establish a foothold and exploit the country’s divisions has been facilitated by the disunity among European and MENA nations in terms of how to approach the country’s instability. Ibrahim criticizes the British and French approach in these years as being “overly optimistic” in their belief that Libyans will eventually establish a stable government. The British, French, and Italians tended to view the post-Gaddafi aftermath through the lens of its resulting refugee crisis, fueled heavily by their own domestic politics. Among MENA states, Qatar and Turkey’s support of the GNU in the west have been motivated in part by their willingness to support Muslim Brotherhood groups in the wider region. By contrast, Egypt and Saudi Arabia’s support for Haftar’s LNA is motivated by their opposition to any Brotherhood gains in the region.22

The 2020 Ceasefire and the Status Quo

The wider civil war that resumed in 2014, despite killing tens of thousands, ended in the inconclusive ceasefire being currently–if imperfectly–observed by the major factions. The 2020 ceasefire agreement is nominally committed to maintaining Libya’s territorial integrity and borders. However, it was mainly intended to end hostilities, with the terms of the agreement recognizing the need for a unified national government to completely resolve the conflict. This brings us to Libya’s 2025 status quo: A “de facto two-state entity,” with “two governments…two legislative bodies, and two security entities.”23 The west is controlled by the GNU, and the east controlled by the GNS. Thus far, the factions have not relapsed into full-blown civil war, but the country has not been free of tensions or violence.

Brooklyn Quallen, writing for Genocide Watch, describes at least two major incidents in 2022 and 2023 where fighting erupted in Tripoli, killing dozens. Security challenges are rife, with human trafficking being a major problem, particularly for migrants passing through Libya on the way to other countries, who often face exploitation and violence.24 Political violence and terrorism have become a major problem, most recently marked by an assassination attempt of a GNU government minister (Al Jazeera 2025). The two leading factions’ control of the country’s southern half is limited, at best, with various armed factions engaging in criminal activity and human trafficking. Resolving Libya’s current divisions and instability is obviously no simple task. But a major problem is that foreign powers have largely come at the Libyan problem from a self-interested “What’s in it for me?” angle that neglects the basic needs of Libyans themselves.25

Conclusion – Facilitating a Foundation for Stability

As noted earlier, European nations tend to view the crisis through its contribution to refugee flows into Europe. In addition, business interests fear being undermined by the country’s instability. As a result, external efforts to help Libyans establish a unified state have failed to address some key issues. The current east-west division has long historical roots, as described earlier in this writing. Various internal actors in this divide have exploited it for their own benefit rather than a genuine desire for national unification. This leaves many Libyans focused on “surviving day by day” without the ability to organize an effective movement that can channel their disillusionment. Most recently, the U.S. and western countries’ foreign policy in the MENA region, exacerbated by their virtually unconditional support of Israel’s campaign in Gaza, has damaged the credibility of western efforts at resolving the conflict.26 The new U.S. administration’s policies towards Israel and Palestine are unlikely to change in a direction that mitigates this view among Libyans.

It is an open question as to whether the United States under Donald Trump has the interest in making a serious, sustained effort to bring the GNU, GNS/LNA, and the various regional actors to the table in an effort to reach a unification deal. However, to succeed, any efforts at achieving unification and long-term stability have to start from a perspective of Libya’s people, and not primarily the interest of external actors.27 The appeal for major players in the Middle East drive their involvement. The current factions and their leadership are unlikely to reach a genuine compromise by themselves, particularly when foreign states fall on different sides of Libya’s division.

To lay the foundation for a stable future, the international community must be willing to provide a sustained investment in Libya’s development, both for its infrastructure and economy. For example, Libya has faced decreasing access to water sources, something that will only worsen the chances of conflict as competition over water and other resources intensifies.28 Outside actors must facilitate the establishment of a unity government that is willing and capable of addressing the concerns of the various actors and, most importantly, those of Libya’s people. It would not be realistic to assume that we can simply remove the current major players, who have contributed much to Libya’s misery, from positions of influence. But it is possible to push for a political settlement that grants them a reasonable amount of political influence while disincentivizing foreign powers from openly supporting one side or the other.

Maintaining an arms embargo that prevents foreign states from supporting either of the factions is only a start. The lifting of this embargo should be conditioned on the establishment of a national military and integrated reformed and professional security force, responsible for the whole country and its people, rather than a specific warlord or political and regional identity. Politically, simply having elections is not enough, as numerous countries in the region have demonstrated repeatedly. Elections require powerful international observers to monitor and safely report on the level of integrity. More importantly, these elections can only provide one democratic institutional element to give everyday Libyans a genuine stake in their country’s future stability, unity, and prosperity as well as institutions that can address grievances. Any elections that can be plausibly viewed as either a benefit to one warlord or another, or as a tool for foreign interests, will be doomed to failure.29 There is no full-proof way to resolve Libya’s current impasse, and the international community must approach it with the expectation that setbacks are likely. Yet, in long-term, the status quo is unsustainable brings great risk for a resumption of the previous decade’s violence and civil war unless meaning change occurs.

- Central Intelligence Agency, 2025, Libya – The World Factbook. Www.cia.gov. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/libya/#people-and-society, retrieved on 3/9/2025. ↵

- Libya – The World Factbook. (n.d.), www.cia.gov. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/libya/#people-and-society , retrieved on 4/12/2025. ↵

- Nikkels, A. (2022). Institutional Change and Identity: Impact of the Arab Spring and Mobilization in North Africa, p. 230, in T. Falola & C. Jacquemin (Eds.), Identity Transformation and Politicization in Africa (pp. 227–243), Lexington Books. ↵

- Quallen, B. (2024, March 26). Libya Country Report, 2024. Genocide Watch. https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/libya-country-report-2024, retrieved 4/12/2025. ↵

- Daragahi, B. (2021, February 17). Ten years ago, Libyans staged a revolution. Here’s why it has failed. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/ten-years-ago-libyans-staged-a-revolution-heres-why-it-has-failed/, retrieved 4/11/2025. ↵

- Nikkels, A. (2022). Institutional Change and Identity: Impact of the Arab Spring and Mobilization in North Africa, p. 229, in T. Falola & C. Jacquemin (Eds.), Identity Transformation and Politicization in Africa (pp. 227–243), Lexington Books. ↵

- Kingsley, P. (2013, March 14). Egyptian police “killed almost 900 protesters in 2011 in Cairo.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/mar/14/egypt-leaked-report-blames-police-900-deaths-2011, retrieved 3/30/2025. ↵

- Kingsley, P. (2013, March 14). Egyptian police “killed almost 900 protesters in 2011 in Cairo.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/mar/14/egypt-leaked-report-blames-police-900-deaths-2011, retrieved 3/30/2025. ↵

- Nikkels, A. (2022). Institutional Change and Identity: Impact of the Arab Spring and Mobilization in North Africa, p. 230, in T. Falola & C. Jacquemin (Eds.), Identity Transformation and Politicization in Africa (pp. 227–243), Lexington Books. ↵

- Kingsley, P. (2013, March 14). Egyptian police “killed almost 900 protesters in 2011 in Cairo.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/mar/14/egypt-leaked-report-blames-police-900-deaths-2011, retrieved 3/30/2025. ↵

- Kilcullen, D. (2013). Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerilla. pp. 222. Oxford University Press. ↵

- Nikkels, A. (2022). Institutional Change and Identity: Impact of the Arab Spring and Mobilization in North Africa, pp. 230-231, in T. Falola & C. Jacquemin (Eds.), Identity Transformation and Politicization in Africa (pp. 227–243), Lexington Books. ↵

- Nikkels, A. (2022). Institutional Change and Identity: Impact of the Arab Spring and Mobilization in North Africa, p. 231, in T. Falola & C. Jacquemin (Eds.), Identity Transformation and Politicization in Africa (pp. 227–243), Lexington Books. ↵

- Nikkels, A. (2022). Institutional Change and Identity: Impact of the Arab Spring and Mobilization in North Africa, p. 231, in T. Falola & C. Jacquemin (Eds.), Identity Transformation and Politicization in Africa (pp. 227–243), Lexington Books. ↵

- Daragahi, B. (2021, February 17). Ten years ago, Libyans staged a revolution. Here’s why it has failed. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/ten-years-ago-libyans-staged-a-revolution-heres-why-it-has-failed/, retrieved 4/11/2025. ↵

- Daragahi, B. (2021, February 17). Ten years ago, Libyans staged a revolution. Here’s why it has failed. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/ten-years-ago-libyans-staged-a-revolution-heres-why-it-has-failed/, retrieved 4/11/2025. ↵

- Rasmi, F. (2021). Beyond the War: The History of French-Libyan Relations. Atlantic Council. p. 7, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep30743, retrieved 4/12/2025. ↵

- Rasmi, F. (2021). Beyond the War: The History of French-Libyan Relations. Atlantic Council. pp. 7-8, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep30743, retrieved 4/12/2025. ↵

- Ibrahim, A. (2020). Rise and Fall? The Rise and Fall of ISIS in Libya Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College. p. 1, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/913, retrieved 4/12/2025. ↵

- Ibrahim, A. (2020). Rise and Fall? The Rise and Fall of ISIS in Libya Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College. pp. 40-42, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/913, retrieved 4/12/2025. ↵

- Ibrahim, A. (2020). Rise and Fall? The Rise and Fall of ISIS in Libya Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College. pp. 49-51, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/913, retrieved 4/12/2025. ↵

- Ibrahim, A. (2020). Rise and Fall? The Rise and Fall of ISIS in Libya Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College. pp. 47, 55, 57, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/913, retrieved 4/12/2025. ↵

- Shennib, H. (2025, January 31). Libya’s De Facto Partition Demands a Solution Designed for it—Not for Outside Contenders. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/libyas-de-facto-partition-demands-a-solution-designed-for-it-not-for-outside-contenders/, retrieved 4/13/2025. ↵

- Quallen, B. (2024, March 26). Libya Country Report, 2024. Genocide Watch. https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/libya-country-report-2024, retrieved 4/12/2025. ↵

- Shennib, H. (2025, January 31). Libya’s De Facto Partition Demands a Solution Designed for it—Not for Outside Contenders. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/libyas-de-facto-partition-demands-a-solution-designed-for-it-not-for-outside-contenders/, retrieved 4/13/2025. ↵

- Shennib, H. (2025, January 31). Libya’s De Facto Partition Demands a Solution Designed for it—Not for Outside Contenders. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/libyas-de-facto-partition-demands-a-solution-designed-for-it-not-for-outside-contenders/, retrieved 4/13/2025. ↵

- Shennib, H. (2025, January 31). Libya’s De Facto Partition Demands a Solution Designed for it—Not for Outside Contenders. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/libyas-de-facto-partition-demands-a-solution-designed-for-it-not-for-outside-contenders/, retrieved 4/13/2025. ↵

- Ibrahim, A. (2020). Rise and Fall? The Rise and Fall of ISIS in Libya Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College. p. 58, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/913, retrieved 4/12/2025. ↵

- Shennib, H. (2025, January 31). Libya’s De Facto Partition Demands a Solution Designed for it—Not for Outside Contenders. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/libyas-de-facto-partition-demands-a-solution-designed-for-it-not-for-outside-contenders/, retrieved 4/13/2025. ↵

24 comments

Rebecca Amaya

An unexpected thing I learned about Libya’s security challenges is that its turning into a volatile battleground because of the absence of a central government, allowing voids to be filled with opportunists like criminals or militias. What resonated the most was the author’s metaphor, “…a tinderbox waiting for a spark…”, because it conjures a visual of peace surrounded by a continual threat of renewed conflict.What realistic steps can be taken to rebuild Libyan national unity in the face of such entrenched factionalism and foreign influence?

Teagan McSherry

It was unexpected to learn how deeply Libya’s security challenges are shaped by foreign interference. The article’s exploration of Libya’s rich cultural heritage and the resilience of its people resonated deeply. Despite the ongoing conflict, Libyans continue to uphold their traditions, values, and sense of community, which I find inspiring. What role do you believe international organizations should play in facilitating a sustainable peace process in Libya?

Sarah

Thank you for covering such a complicated and sensitive situation with so much detail and depth! I appreciated how you compared the Arab Spring in other countries (such as Egypt and Tunisia) to Libya. It’s hard to wrap our minds around all of these things happening at once, and being sparked by one man’s protest in Tunisia. The country reminds me vaguely of Sudan (which I just wrote a paper on for another class), especially in terms of the civil war and paramilitary dynamics. In conflict transformation, we studied the role of women in peacebuilding. Do you think that empowering women in their role in peace would help lead to more sustained peace in Libya?

Carollann Serafin

1) I was most interested in learning about how the war in Libya actually started and what led to it. While learning what occured and seeing how it is still occurrence and how this has factored into daily day life.

2) The best portion of this story was learning about you included the impact of how the people were impacted and the hardships and challenges they faced.

3) My. portion would be asking what was your inspiration by researching this question and what would you have done differently.

TJ

This piece does a good job of explaining why Libya is in a tough spot. The writer points out how its size and where people live make things less stable. The split between the east and west, and how other countries are involved, makes the situation clearer. The writing connects what happened during the Arab Spring to the problems now, which helps explain things. The example of ISIS shows how the country’s divisions can be used. The author also thinks about how other countries can help and what might make things better.

Cynthia Brehm

Great paper Ruben, your analysis was very insightful. I especially appreciated the question you raised in your conclusion about whether the international community can lay a stable foundation in Libya. It’s an important one.

After all, it was the international community that helped shape the Libya we see today, particularly through the UN’s invocation of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) in 2011. In many ways that intervention created more chaos than stability. So now that Libya is in turmoil, can we really expect the same actors to come in and stabilize such a volatile and fragmented country?

You mentioned the need for rebuilding infrastructure, but I wonder—would that kind of investment actually reach the people, or would it be misused as we have seen in other regions? Hamas, for example has diverted aid toward weapons instead of civilian needs. Could Libya’s factions do the same? Do terrorist groups even care about infrastructure or good governance?

At times, Libya feels like a modern-day “Wild West,” where lawlessness enables terrorism, smuggling, and human trafficking to thrive. Stabilization would require more than just money—it would require force, oversight, and a unified strategy. Right now, I do not see the political will for that.

As for water issues, your point reminded me of Sarah Etter’s writing on Egypt. She noted that nine countries dependent on the Nile, yet Ethiopia built the GERD and no one could stop them because they are sovereign and they sit at a higher elevation. Meanwhile Saudia Arabia and Israel have turned to desalinization plants to solve their water crises. I believe Libya should follow suit and invest in desalinization technology as a long term solution to its water shortage.

Micaella Sanchez

Libya’s ongoing division reflects the deep scars left by decades of dictatorship, foreign intervention, and failed reconciliation. The absence of unified governance and effective foreign policy has prolonged instability. This shows the effects of it in the story. This analysis highlights the urgent need for accountable international engagement and a Libyan-led political process. It can also serve as an informative example to those around the world.

Lashanna Hill

What was unexpected to me in learning about their security challenges was that their demographics plagued the country’s political situations since 2011. The best part of the story that resonated with me was the explanation of the two major factions that are supporting the East and West division, causing more problems than resolution.

Should Libya refocus and shift their military efforts from international assistance and interference to prevent future civil wars?

Mia Ramirez

What I found most interesting in this article is that Libya is facing serious and ongoing problems due to two rival governments. The revival is based from the west to the east, which are the Government of National Stability, and the Russa’s Wagner private military company. What resonated the most in this article is that stabilizing Libya requires more than just enforcing arms and holding elections. With that being said, my question is: How should Libya state officials moderate fair elections?.

Jesse Turnquist

I found this to be a very good read on Libya. We discussed in a prospect professor’s class discussion what might have happened if foreign governments did not get involved, and whether they did everything possible to stop the conflict before taking military action. Libya was a very successful country with fast-moving progression; however, after the fall of Gaddafi, things took a turn for the worst, leaving the people in Libya with a humanitarian crisis. What surprised me the most is the lack of support for peace in the region by foreign governments. What is the best path toward peace for the people of Libya?