For almost as long as personal computers have been in existence, Microsoft seems to be the company that has dominated the market. The Microsoft Corporation is a company that produces software, electronics, video game consoles, and computers, along with other technological advances. The world is no stranger to the effect that Microsoft has had on i,t and even labels it one of the most impressive companies, taking into account both its products and its revenues. With its worldwide impact, it is still thought to be one of the leading companies in the industry. Though the world’s dependence on Microsoft has slightly decreased, there was a time when Microsoft completely conquered its competition, monopolized it even. And the world definitely noticed. In 1998, the United States Department of Justice accused the Microsoft Corporation of violating the policies of the Sherman Antitrust Act, more specifically its sections 1 and 2.

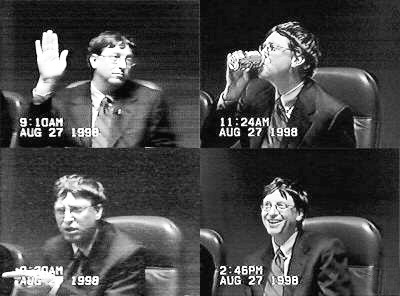

Microsoft was founded in 1975 by Bill Gates and Paul Allen. They began to gain recognition when they created the first operating system for the IBM PC, the Microsoft disk operating system, or MS-DOS. They grew when they followed this innovation with the first version of Windows operating system and Office software, and soon became a technology empire. However, their extraordinary success and position in the industry led them to be investigated by government antitrust enforcers on numerous occasions. In May of 1998, fueled by the pending release of Windows 98, the U.S. Department of Justice and twenty states “accused Microsoft of pursuing a wide-ranging campaign to destroy its principal browser rival, Netscape Communications, in order to obstruct competition in the emerging market for browsers and to perpetuate its monopoly of operating systems” in what became known as the United States v. Microsoft case.1 In what became a popular case that captured the attention of legal and business entities, technology companies and promoters, and even the general public who were dependent on their Microsoft products in their daily lives, Microsoft was suspected to be a monopolistic company that violated the Sherman Antitrust Act.

* * *

To understand what really took place during the U.S. v. Microsoft case, it is first crucial to understand the United States’ antitrust laws. The federal antitrust laws are made up of three major statutes: The Sherman Act of 1890, the Clayton Act of 1914, and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914.2 These laws are mainly enforced by the Federal Trade Commission, the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice, and private parties. The overall goal of the Antitrust laws is to protect competition and ensure fair market policies for all companies; the antitrust policies have developed in order to protect the economic markets from being completely dominated by one company, entity, or firm.

The first of the legal statutes against monopolies was The Sherman Act. The main goal of the Sherman Act was to give power of enforcing the antitrust law to the executive branch of government. The “rule of reason” principle outlined in the Sherman Act is used when the court compares the competitive features of a restrictive business practice against its anticompetitive effects in order to decide whether or not the practice should be prohibited. Because of the “rule of reason” that the courts used to determine the unreasonable conduct outlined in the Sherman Act, “businesses had little guidance as to what was illegal and courts had no specific mandate to enforce.”3 So, the Clayton Act was passed in order to give more guidance in the breaking of monopolistic practices. The Federal Trade Commission Act later “declared unlawful unfair methods of competition and deceptive trade acts.”4 A case that set a precedent for other antitrust cases, and even led to the development of the Clayton Act, was the case that the United States took against Standard Oil Company. Standard Oil was founded by John D. Rockefeller and dominated about eighty to ninety percent of oil production through horizontal and vertical integration techniques. The government, however, intervened and split up the company based on its anticompetitive practices into thirty-four different, smaller companies. ExxonMobil and Chevron are among the smaller companies that Standard Oil split into. This is one of the first instances where the government began to get involved, and it definitely paved the way to future endeavors, such as the Microsoft case.5

* * *

Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act that the United States claimed the Microsoft Corporation violated, “declares unlawful ‘every contract, combination in the form of a trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce.’”6 The court has deemed practices such as price-fixing, exclusive dealing, resale price maintenance, and tying as illegal according to section 1.

The plaintiffs in the U.S. v. Microsoft case claimed that Microsoft’s integration of their Internet Explorer browser in their Windows operating system constituted as a means of tying, and therefore the consumers were forced to obtain Internet Explorer if they wanted Windows. Microsoft initially tied Internet Explorer to Windows by ensuring that computer manufactures who licensed Windows 95 also installed Internet Explorer. Microsoft also made sure to sell the bundled products together at retail. Then in 1996, in order to truly guarantee that the two products were inseparable and that consumers had no option but to choose them, Microsoft made it so that computer manufacturers who licensed Windows could not remove the Internet Explorer icon from the Windows desktop, could not add any other icons that would surpass the Window’s icons, and could not alter the boot sequence or add programs that open at the end of the boot sequence. These restrictions were placed on the computer manufacturers, so that the consumers would not have an initial option to choose Netscape’s browser Navigator over the Windows browser Internet Explorer. Also in 1996, Microsoft began physically assimilating the Internet Explorer browser into Windows by adding Internet Explorer code into Windows 95. When this was done, Internet Explorer could still be removed with Window’s Software Uninstall function, but with the introduction of Windows 98, consumers were even left devoid of this option.7

* * *

“Tying under section 1 exists where (1) there are two distinct products; (2) the defendant requires customers to take the tied product as a condition of obtaining the tying product; (3) the arrangement affects a significant volume of commerce; and (4) the defendant has market power in the tying product.”8 In Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Technical Services, Inc., eighteen independent service organizations, or ISOs for short, who oversaw the servicing and providing of replacement parts of Kodak photocopying equipment, brought about the claim that Kodak was violating section 1 of the Sherman Act through their new policy of selling its photocopier replacement parts only to those consumers who used its repair services. The ISOs believed that Kodak had tied the servicing for Kodak equipment to the Kodak replacement parts. However, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California found that there was no evidence to support the claim that Kodak tied the sale of its replacement parts and service to the sale of its photocopier equipment. Kodak was adamant about the fact that they did not force the consumers to buy the services in order to receive the replacement parts, but rather they just had to agree not to buy the ISO’s services in order to receive the parts. The case went to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which ended up reversing the judgement. They stated that it is also unlawful for a product to be conditioned on the fact that services will NOT be bought. The biggest dilemma in this case was to prove the fourth clause of tying under section 1, that Kodak did indeed have market power in the product. Kodak suggested that if buyers found their conditions and prices overbearing and high, they would switch to the other companies offering the same products and services, and thus Kodak could not take such actions and were not a dominant force in the market. In what became an unexpected decision, the court refused this statement because it was a theory and not a fact. The case was a factual matter and Kodak was bringing up an economic theory that did not reflect the photocopier market realities. Consumers could not easily switch to another provider as Kodak had stated and were rather “locked-in” and forced to choose Kodak if they had already bought their products.9

This case was monumental in changing how the court decided antitrust cases and “in future antitrust cases, it now appears that parties will be forced to factually demonstrate the effect on competition caused by the challenged conduct.”10 Just as the tying and Sherman Antitrust allegations that were formed in this case set a precedent for future antitrust and tying cases, the U.S. v. Microsoft case did the same for many technology related cases that came after it. And just as Kodak “locked-in” their buyers, Microsoft, and many other companies, were accused of taking the exact same measures in order to ensure that buyers stayed with their company and product.

* * *

Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act depends highly on the fact that Microsoft was indeed a monopolistic company. Section 2 rebukes “‘every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations…’ The courts have defined ‘monopolization’ as having two elements: ‘(1) the possession of monopoly power in the relevant market and (2) the willful acquisition or maintenance of that power as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historical accident.’”11 As Microsoft’s share in worldwide PC operating systems at the time of the case was about ninety-five percent, the court claimed that Microsoft was a monopoly and tried to maintain its monopoly by entering into exclusionary contracts with computer manufacturers, Internet access providers, Internet content providers, and software vendors.12

Beginning in 1996, Microsoft made exclusionary contracts that tied gaining Windows to the acceptance of the contracts with fourteen large Internet service providers. “These firms were told that they would be placed in the Windows Internet Connection Wizard—which made it easy for consumers to subscribe to and download access software from Internet service providers—if and only if they agreed to certain restrictions, which included a promise not to offer other browsers to customers nor to offer web links to other browsers.”13 They were, on rare occasions, allowed to provide another browser if the customers really desired it, but Microsoft’s contracts required that seventy-five to eighty-five percent of the browsers offered be Internet Explorer. Microsoft also entered into contractual relationships with four online services, and similarly tied gaining Windows to the acceptance of these contracts. In “1997, Microsoft also began writing exclusionary contracts with Internet content providers which tied placement in the Windows Channel Bar, which allowed consumers who enabled the Windows Active Desktop to connect more easily to a content provider’s website, to making Internet Explorer their preferred browser… Finally, Microsoft also wrote contracts containing exclusivity provisions with some software vendors. For example, in June 1997, Intuit (maker of Quicken) promised not to distribute any other browser with its software.”14

These contracts and other practices have greatly paved the path for Microsoft’s stance in the market, as “the dominance of Windows in the market for operating systems is due in large part to its success as a software platform—that is, to the fact that a great many software developers write application programs solely for the Windows operating system.” The contracts and the fact that writing applications programs that are enabled to run on other less popular operating systems can be expensive, Microsoft has created a sort of “applications barrier to entry” for the market of operating systems.15 This simply means that with Windows there was a barrier that thwarted operating systems other than Windows from gaining a lot of buyer support, and it would continue to do this even if Microsoft made its prices substantially higher than their competition’s. Thus, this is yet another example of how a dominant company has locked-in their consumers, as there are no other alternatives or means to switch to another company offering the same services or products.

* * *

If a buyer signs an exclusive contract, all other sellers are foreclosed from competing for that buyer’s business, and because Microsoft is the most dominant in the market, programmers and producers of software make their programs to fit the specifications of Microsoft products.16 This restricts consumers from being able to use Microsoft’s competition’s products and services, as they weren’t as readily available as Microsoft’s products. This practice of “vendor lock-in” has been in existence in the world for far longer than the Microsoft case, and makes customers reliant on one company as they are unable to switch or go to others.

In Charoensak v. Apple Computer, Inc., or what was formerly called Slattery v. Apple Computer, Inc., the plaintiffs alleged that Apple was utilizing their FairPlay Digital Rights Management (DRM) system in order “lock-in” their customers and maintain their monopoly in the market. They claimed that Apple was violating sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act and other antitrust acts. DRM technology is used to regulate usage and distribution of copyrighted materials and also control systems in devices. Apple developed their FairPlay technology in a way that “songs purchased from iTunes came embedded with software that made them incompatible with other music players, and the iPod was made so that it couldn’t play songs purchased from competing online music stores.”17

This was possible because Apple did not license their DRM to other companies, thus making Apple devices and programs the only products that could play the encrypted iTunes music. “Thomas Slattery’s original complaint was that FairPlay was ‘an artifice that prevents consumers from using the portable hard drive digital music player of their choice.’”18 This statement truly encompasses what vendor lock-in is, as it is a way for a company to not give their consumers any other options. Apple wanted to ensure that their customers were going to stick to, or rather be forced to, using their products and services, so used this technology in order to make it happen. However, after the case was brought to light, Apple removed DRM from the iTunes music in 2009, while still keeping the DRM technology on videos purchased.19 After many years of lawsuits, complaints, and other cases, the jury eventually decided in Apple’s favor because the new version of iTunes did not have the DRM technologies and was not really a harm to consumers. The judgement saved Apple an estimated $1 billion dollars, but the cases and consumers led the way for change in their vendor lock-in practices.

* * *

The U.S. v. Microsoft case began in 1998, and finally on June 7, 2000, Judge Thomas Jackson ordered the breaking up of Microsoft into two companies because of its monopolistic and excluding behaviors. This ruling had the potential to bring about great change to the software and technology industry, as this would be the “largest single enforced dismantling of a corporation since the Standard Oil Trust was split into thirty-four companies in 1911.”20 And through this example, many other software companies were already beginning to implement changes to their own restrictive practices. Judge Jackson’s ruling was, of course, appealed by Microsoft and the case went to the Court of Appeals for the D. C. Circuit. “In a serendipitous twist of fate for Microsoft, Jackson was removed from the case for speaking with reporters before announcing his final decision, [and] U.S. District Judge Colleen Kotar-Kotelly replaced him and approved a settlement.”21 Although Judge Jackson’s ruling to split Microsoft into two companies was denied, “the appeals court agreed with both Jackson’s monopoly ruling and his findings that Microsoft illegally maintained its monopoly. In October 2001, Microsoft agreed to terms to settle the lawsuit out of court.”22 The Department of Justice and Microsoft reached a settlement on November 2, 2001 in which Microsoft “agreed to disclose sensitive technology to its competitors…to allow manufacturers and customers to remove Microsoft icons from some of the features in the company’s system software,” and also to adopt a three-person panel that would make sure they were satisfying the stated agreements.23 “It was extended twice before expiring in May 2011.”24

Even though Microsoft did not get split into two companies, there were effective measures taken to make sure that Microsoft’s monopoly in the operating system and software market could not continue. Even with these changes, Microsoft proved its dominance by still being able to suppress competitors and become one of the greatest companies in the world. This case set the precedent to many cases of monopolistic practices that occurred in the technology field, as the government was not as involved in this market as it was after this case. It showed large, dominating technology companies that future government interference was possible and would take place.

- Andrew Gavil and Harry First, The Microsoft Antitrust Cases: Competition Policy for the Twenty-first Century (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2014), 1-2. ↵

- Andrew Gavil and Harry First, The Microsoft Antitrust Cases: Competition Policy for the Twenty-first Century (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2014), 7. ↵

- Research Starters: Business, January 2017, s.v. “Law of Marketing and Antitrust,” by Seth Azria. ↵

- Research Starters: Business, January 2017, s.v. “Law of Marketing and Antitrust,” by Seth Azria. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “John D. Rockefeller,” by Judith Trolander. ↵

- David Evans, Microsoft, Antitrust and the New Economy: Selected Essays (Boston: Springer, 2002), 4. ↵

- Michael Whinston, “Exclusivity and Tying in U.S. v. Microsoft: What We Know, and Don’t Know,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 15, no. 2 (2001): 64. ↵

- Historic Documents of 2000 (Washington D.C.: CQ Press, 2001), 121. ↵

- Jill Protos, “Kodak v. Image Technical Services: A Setback for the Chicago School of Antitrust Analysis,” Case Western Reserve Law Review 43, no. 3 (1993): 1199. ↵

- Jill Protos, “Kodak v. Image Technical Services: A Setback for the Chicago School of Antitrust Analysis,” Case Western Reserve Law Review 43, no. 3 (1993): 1199. ↵

- David Evans, Microsoft, Antitrust and the New Economy: Selected Essays (Boston: Springer, 2002), 6. ↵

- Michael Whinston, “Exclusivity and Tying in U.S. v. Microsoft: What We Know, and Don’t Know,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 15, no. 2 (2001): 64. ↵

- Michael Whinston, “Exclusivity and Tying in U.S. v. Microsoft: What We Know, and Don’t Know,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 15, no. 2 (2001): 65. ↵

- Michael Whinston, “Exclusivity and Tying in U.S. v. Microsoft: What We Know, and Don’t Know,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 15, no. 2 (2001): 65-66. ↵

- Benjamin Klein, “The Microsoft Case: What Can a Dominant Firm Do to Defend Its Market Position?,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 15, no. 2 (2001): 45. ↵

- Michael Whinston, “Exclusivity and Tying in U.S. v. Microsoft: What We Know, and Don’t Know,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 15, no. 2 (2001): 66. ↵

- Jeff Ward-Baile, “Aided by Steve Jobs’ Testimony, Apple Prevails In iTunes Antitrust Case,” Christian Science Monitor, Dec. 16, 2014. ↵

- “Steve Jobs’ Other Legacy: Anti-Trust,” MacUser 31, no. 1 (January 2015): 11. ↵

- “Steve Jobs’ Other Legacy: Anti-Trust,” MacUser 31, no. 1 (January 2015): 11. ↵

- Historic Documents of 2000 (Washington D.C.: CQ Press, 2001), 308. ↵

- Gale Encyclopedia of E-Commerce, June 2012, s.v. “Microsoft Windows.” ↵

- Mary Puthawala, “Microsoft Corporation,” in Computer Sciences, ed. K. Lee Lerner and Brenda Wilmoth Lerner (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2013). ↵

- Gale Encyclopedia of American Law, June 2010, s.v. “Software.” ↵

- Gale Encyclopedia of E-Commerce, June 2012, s.v. “Microsoft Windows.” ↵

22 comments

Adam Alviar

I myself prefer both apple and Sony over Microsoft, but this was a great informative article on the Microsoft Monopolization Case. This article had a great way of relaying the information of who and what Microsoft is along with the way the case was handled. It seemed like it didn’t need all of this attention it did seem to cease the problem with a fair agreement towards the end, even though the case did not seem to change the dominance of Windows in the software market.

Amariz Puerta

Although I have not really been a microsoft fan I really enjoyed reading this article. I had really not known about either apple or microsoft’s history but reading this I was able to gain a lot of knowledge. I thought it was interesting to see that they went to court and had to defend themselves. I really enjoyed reading this article!

Donte Joseph

I had always been a fan of Microsoft because of how fast they were advancing in technology, but I had no prior knowledge of their history. Hearing that they were accused of monopolization I am not surprised, but the fact that they had to go to court to defend their selves is something that I still cannot believe. I did enjoy reading more about a company that is very well respected.

Luisa Ortiz

I really like the opening of this article! starting with the juicy things without giving it all away, as millennial growing up with technology, I never knew that the company Microsoft was pretty much in charge of all technology like video games, needless to say, I was unaware of the case! (DRAMA), besides the amazing article, I really enjoy the pictures!

Mariana Valadez

I had no idea there was a case against Microsoft. Microsoft has been extremely innovative throughout years. It is crazy that they could have been potentially split into two companies. I never would have imagined for a company like this to be accused of these things. It was interesting to read the exact details of what happened in this case.

Andrea Cabrera

I really enjoyed and loved reading the article. Microsoft has improved technology in so many ways that were unimaginable just decades ago. I never thought that a company this big in today’s actuality, which I personally preferred more than other servers, would had been accused and had to fight in order built a case against its competitor’s accusations, for us to be able to take advantage of such great innovation.

Andrea Cabrera

I really enjoyed reading the article. Microsoft has improved technology in so many ways that were unimaginable just decades ago. I never thought that a company this big in today’s actuality, which I personally preferred more than other servers, would had been accused and had to fight in order built a case against its competitor’s accusations, for us to be able to take advantage of such great innovation.

Alexandra Cantu

Good article! Miscrosoft has been one of them favorite technology company over the Years. Microsoft was doing innovative things. I never knew about the case against it, but it was interesting to read the details about the case. I did not know that they violated and how they violated it. I enjoyed reading this article about Microsoft! Once again good job.

Hector Garcia

Overall, I thought that the topic of this article was quite interesting. The author made several good points on Microsoft’s monopoly on their computer system. The company’s actions seemed like they were ripping off the consumers by forcing them to buy Internet Explorer. Another example, Slattery v. Apple Computer, was able to convey the topic that the author wanted to address.

Isaac Rodriguez

This article was an interesting read. As a consumer who uses Microsoft products every day, it is funny to think that they could have been split into two companies. I am surprised that despite the measures taken to prevent Microsoft from monopolizing, they control many of the markets today. But thankfully, Bill Gates is a modest person and a generous philanthropist.