For decades, Latinos in the United States did not have a political voice. At the age of twenty-three, Willie Velásquez decided to change this. He worked to ensure the empowerment and participation of Chicanos in U.S. democracy, a project that would become his life’s work. Velásquez’s motivation to educate Latinos showed his commitment to the values of American democracy. As Henry Cisneros, former Latino mayor of San Antonio remembered Velásquez, “[Willie’s] legacy is large in the hearts and minds of those of us who knew and worked with him.”1

Before becoming a Mexican American political activist, Velásquez attended college at St. Mary’s University. In 1967, he and other Latino-Chicano students, known as Los Cinco (The Five), created the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO).2 MAYO worked to register Chicano youth to vote, and the group defended farm workers’ rights by becoming one of the anchors of the Chicano Movement. The group popularized the motto Su Voto Es Su Voz (Your Vote is your Voice). They spread their message through local newspapers and city-to-city events to bring other young people into the organization.3

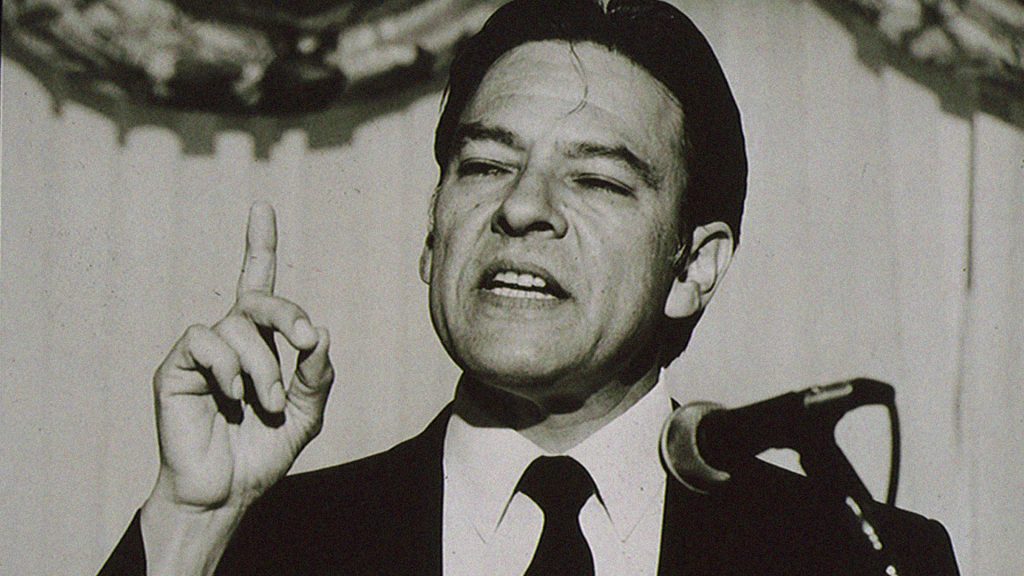

As a St. Mary’s student, Velásquez involved himself in volunteer work, where he began to develop leadership skills, offering a helping hand to others while continuing the Marianist heritage of civic engagement. Velásquez signed up to help farm workers who were on strike because he saw the realities of their conditions and their mistreatment by the Texas Rangers. Conditions worsened for the farm workers as the Texas Rangers continued to make discriminatory arrests, and unreasonable beatings on the strikers escalated. Velásquez decided he needed a big political voice to speak for the farm workers. During his third internship in Washington D.C., Velásquez visited Congressman Henry B. González, who became his first political mentor. González’s vision and passion for helping the voiceless attracted Velásquez to the congressman. He wanted González’s support for the migrant workers, yet González declined to help since it was out of his district. From that point on, Velásquez and González became political opponents.4

In 1969, González made his first attack against MAYO. In a speech, he characterized the activists as members of a movement driven by “race hate.”5 José Ángel Gutiérrez, one of MAYO’s founders, held a press conference answering González’s attacks, stating that MAYO was going to take the necessary means to “eliminate their enemies”.6 In contrast, Velásquez answered the congressman’s attacks by appealing to American values, such as equality, unity, liberty, and progress. He stated that in all of their efforts working for San Antonio’s community, they were never called “traitors to our country.”7 After the speech, the public responded by inviting the congressman to observe the good works from these Chicano activists. 8

Early in 1970, several San Antonio students formed the Chicano Coalition of College Students (CCCS). Velázquez’s brother George and soon-to-be wife Janine played major roles in the Coalition. When the students heard that St. Mary’s University invited Congressman González to speak, they planned a walkout. Velásquez attended as a supporter of his brother’s efforts and witnessed the public humiliation of his former mentor. After ten minutes of the congressman’s commentary against the Chicano ideals, the activists started leaving. The congressman noticed Velásquez in the crowd, and he challenged him to a fight. The physical confrontation with the congressman did not end well for Velásquez. After, Velásquez made a public statement proclaiming that every time Henry B. González did something wrong, he was going to be there to make it right. With that declaration, Velásquez launched a lifetime effort to discredit González. While most political quarrels between González and other activists were resolved, González and Velásquez’s feud lasted throughout Velásquez’s life.9

Voting is a fundamental right of U.S. citizens. When Velásquez left MAYO, he created the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project (SVREP) in 1974, and the organization registered 2.3 million Latino voters. Ten years later, it had doubled the number of Latinos registered to vote to about 4 million.10 Velásquez was a light and hope for Latinos in the United States. As Julian Castro, former San Antonio mayor, once said, “I hope that someday when a Latino/a has his/her hand on the Bible getting sworn as the president of the United States that they’ll be thinking about Willie and his work.”11 As Americans, it’s our duty to highlight the importance of the achievements our ancestors attained, as well as the adversities they went through. Citizens owe respect to the activists that have helped shaped our country. Nowadays, registering to vote is as easy as filling out a registration form and sending it by mail, submitting it online, or delivering it directly to the voter registration office. Everyone has a voice and has the right to be heard.

- Juan Sepúlveda, The Life and Times of Willie Velásquez: Su Voto es Su Voz (Texas: Arte Publico Press, 2003), vii ↵

- Wikipedia, 2018, s.v. “Mexican American Youth Organization.” ↵

- Texas State Historical Association Encyclopedia, 2010, s.v. “Mexican American Youth Organization,” by Teresa Palomo Acosta. ↵

- Juan Sepúlveda, The Life and Times of Willie Velásquez: Su Voto es Su Voz (Texas: Arte Publico Press, 2003), 44, 53-56 ↵

- Juan Sepúlveda, The Life and Times of Willie Velásquez: Su Voto es Su Voz (Texas: Arte Publico Press, 2003), 86. ↵

- Juan Sepúlveda, The Life and Times of Willie Velásquez: Su Voto es Su Voz (Texas: Arte Publico Press, 2003), 86. ↵

- Juan Sepúlveda, The Life and Times of Willie Velásquez: Su Voto es Su Voz (Texas: Arte Publico Press, 2003), 88. ↵

- Juan Sepúlveda, The Life and Times of Willie Velásquez: Su Voto es Su Voz (Texas: Arte Publico Press, 2003), 83-88. ↵

- Juan Sepúlveda, The Life and Times of Willie Velásquez: Su Voto es Su Voz (Texas: Arte Publico Press, 2003), 104-108 ↵

- Antonio González, interviewed by Joe Nick Patoski, Voices of Civil Rights, June 2004. ↵

- Willie Velásquez: Your Vote is Your Voice, directed by Hector Galán (Arlington, VA: PBS Distribution, 2016), Documentary. ↵

32 comments

Aaron Sandoval

This article was a pleasant read, in my opinion, I feel like there have been many historical figures that have come from St. Mary’s and they get little recognition on campus. I have heard of Willie Velasquez, but I was not aware of his feud with Representative Henry B. Gonzalez. Velasquez was an impactful leader in San Antonio, and I am glad articles like these are getting written so that others can learn of him.

Kat

Question: Is Velasquez Drive on the St. Mary’s campus named after Willie Velasquez, and if so, when was it named that?

Olivia Tijerina

I particularly loved the topic the author chose to write in this article because it runs off the bases of telling a story of a St.Mary’s Student doing the continuing the heritage, service I had done myself recently. I personally got to know of Willie Velásquez’s story in 12 grade from my Mexican American History class in highschool. In those moments I’ve met an author who wrote a book of the life of Willie Velásquez and at her book launch I got the greatest opportunity to meet Willie Velásquez’s family.

Scott Sleeter

Nice article on an important part of Latino history. It is nice to hear the sound of other historical voices remembering important parts of the past that are ignored in the mainstream. This is what Public History is about. It really gives a chance for other stories to be told and remembered. It gives a chance for people to be inspired by a wide variety of heroes.

Shine Trabucco

I had never heard of Willie Velazquez until coming to St. Mary’s University. You do a good job acknowledging all of his successes. I would try to work on the timeline to make things more clear and also note the names in Los Cincos, as they are important contributors. I really like the Julian Castro quote and find it very fitting with present news

John Cadena

all in all, I related most to this article and I think as a result I found myself weaving in and out of the plot point within the narrative arc with ease. well throughout the entire article I felt the writer did an excellent job and keeping the reader engaged through the use of scene construction, exposition, atmosphere, setting, and space. I find it hard to believe though, this wasn’t simply a result of a already well established passion for this topic.

John Cadena

a really good job of choosing the scene was done in writing this article. As I read this article I was able to recognize were focus was kept on the protagonist well throughout the article. As the story progressed, I was able to see the protagonist go though the various stages of the narrative arc.

Gabriel Cohen

Thanks for writing this article! I just completed my term project last semester on Henry B. Gonzalez, and I spent a great amount of time discussing the relationship between Gonzalez and Velasquez. I think you did a great job of presenting this story from Velasquez’s point of view.

Edgar Velazquez Reynald

Being new to San Antonio, it is great to learn more about local heroes, especially one that has close ties to St. Mary’s! Part of the reasons I have enjoyed my new life in San Antonio is seeing the impact Latinxs have had in the culture of the city. I now have another chicano figure to look up and read more about. Thank you very much for your article.

Danielle A. Garza

Willie and Henry are two major historical voices in the San Antonio Community. I believe you were trying to talk about their quarrels and differences from Willie Velasquez’s point of view. One thing I am confused about is when you talk about MAYO it sounds like he created it as a student in St. Mary’s University or not. All this could be helped by placing a timeline or general dates into your article for reference.