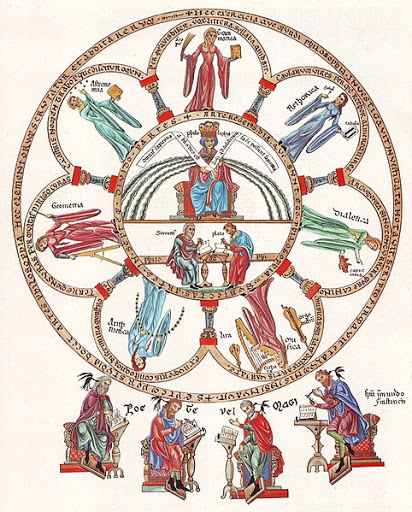

The Seven Liberal Arts. While the phrase “Liberal Arts” is nothing new to any student’s ears, the specific term “Seven Liberal Arts” might not have the same sense of familiarity. The term “liberal arts” comes from the Latin word “liber,” which means “to free”; thus it was believed that the Seven Liberal Arts would “free” one through the knowledge gained in each of various disciplines.1 The term “Seven Liberal Arts” or artes liberales refers to the specific “branches of knowledge” that were taught in medieval schools. These seven branches were divided into two categories: the Trivium and the Quadrivium. The Trivium refered to the branches of knowledge focused on language, specifically grammar, rhetoric, and logic. The second division, the Quadrivium, focused on mathematics and its application: arithmetic, astronomy, geometry, and music.2 Greek philosophers believed the Liberal Arts were the studies that would develop both moral excellence and greater intellect for man. However, it was not from the Greeks, but rather from the Romans that we see the first official pattern or grouping of the Seven Liberal Arts. The beginnings of this pattern came from the Roman teachers Varro and Capella. Varro (116 BCE-27 BCE), a Roman scholar, is credited with writing the first articulation about the Seven Liberal Arts.3 However, Capella (360 AD-428 AD) in his Marriage of Philology and Mercury, set the number and content of the Seven. Branching off of Capella’s work, three more Roman teachers—Boethius, Cassiodorus, and Isadore—were the ones who made the distinctions between the Trivium and Quadrivium.4 Through the writings and research of these men, the foundation for the Seven Liberal Arts was set and ready to be taught officially in the Medieval schools across Europe.

The first division of the liberal arts was called the Trivium which means “the place where three ways or roads meet.” The Trivium was the assembly of the three language subjects or “artes sermoincales”: grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric.5 It was expected that all educated people become proficient in the Latin language. After so many years of school with Latin being the spoken language, the student would be deemed proficient in the language and he would begin studying the higher-level curriculum.6 Completion of the Trivium was equivalent to a student’s modern day bachelor degree.7

The grammar aspect of the Trivium aimed to have students critically analyze and memorize texts as well as produce their own writings. One of the most famous grammatical texts studied by students was the Doctrinale of Alexander of Villedieu, which was a work of verse written in 1199. Naturally, the classics, such as Virgil, were studied as well as some Christian texts.8 In the stronger monasteries, other pagan authors besides Virgil were also studied.9 Not only was Virgil studied, but Donatus and Priscian wrote two very popular textbooks for the study of grammar. Donatus’ work was seen as an elementary work because he focused on the eight parts of speech. Priscian’s work, on the other hand, dealt with more advanced grammatical topics, and he cited some of the Roman forefathers of the Seven, such as Capella, Augustine, and Boethius.10

The student interest level in dialectic had been immense since the early days of the Greek schools, since they focused on the arts of reasoning and logic. For some, such as Rhabanus Maurus, dialectic was considered “the science of sciences.” The commonly studied dialectic textbooks were translations of the famous Greek teacher Boethius’ Categories and De interpretatione of Aristotle. By the twelfth century, the study of dialectic, or logic, came to be seen as the major subject of the trivium.11

The final academic aspect of the Trivium was rhetoric, which focused on expression as well as some aspects of history and law. Again, Boethius had some famous works that were studied in this discipline, but the common textbook was the Artis rhetoricae by Fortunatianus. Grammar and rhetoric were encouraged to a greater extent in the first half of the Middle Ages because knowing Latin was essential.12 The Carolingian period saw the expansion of the discipline of rhetoric grow to include prose composition. This discipline set the groundwork for the studies of canon and civil law in medieval schools.13

The Quadrivium, whose Latin translation is “the place where the four roads meet,” was the assembly of the four mathematical subjects or artes reales: arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy.14 These four areas of study were more advanced than those of the Trivium. Because of this, completion of the Quadrivium would result in the student being awarded a Masters of the Arts degree.15 For Medieval education, all the liberal arts subjects were seen as complementary to ones theology lessons, all of which every educated student would received. The Church encouraged the completion of liberal arts education so strongly that one could not even be ordained a priest if they weren’t deemed proficient in what the Quadrivium demanded.16

The first discipline of the Quadrivium, arithmetic, focused on the qualities of numbers and their operations. When the Arabic notation gained popularity, its methodology was implemented into study, thus increasing the content and understanding of arithmetic.17 The Church had very specific requirements for a man to be deemed proficient in arithmetic. For example, unless a man was able to compute the date of Easter using the writings of the Venerable Bede, he would not be allowed to be ordained into the priesthood.18

The second aspect of the Quadrivium was music. At first, the extensive music courses aspired to produce worship music. Not only did these courses include composition of music, but also performance aspects. The invention and early use of the organ in the medieval churches caused the interest in music to increase.19

Geometry was a new academic aspect for the Medieval world. Up until the tenth century, medieval knowledge of geometry was extremely limited. The discipline focused on geographical and geometrical components. More specifically, the focus was towards the practical applications of surveying, map making, and architecture. The works of Ptolemy were the basis for instruction for geometry. From the work of Ptolemy came further understandings of botany, mineralogy, and zoology.20

The final aspect of the Quadrivium was the teachings of astronomy. However, is was more than understanding how to read the stars. At first, Astronomy was used for arranging the feast days and fast days for the church.17 It also included more complex mathematics and physics. The purpose here was to be able to create and predict the calendar for the church as well as the most advantageous times for harvesting and planting crops. For this discipline, the works of Ptolemy and Aristotle were studied.22

The Seven Liberal Arts. A previously forgotten, but important foundation to our modern-day educational system. The specific disciplines were great, not only from an academic stand point, but in the contributions they held for society. A lot has changed for academia since the medieval period, but if not for the work of our medieval forefathers, how academia changed towards our experiences in the modern day could have been very different.

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts,” by Otto Willmann. ↵

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts,” by Otto Willmann. ↵

- New World Encyclopedia, 2017, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts.” ↵

- S. E. Frost, Essentials of History of Education (New York: Barron’s Educational Series Inc, 1947), 73. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 235; The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts,” by Otto Willmann. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- New World Encyclopedia, 2017, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts.” ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 236. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 236. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 236-237. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 237. ↵

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts,” by Otto Willmann. ↵

- New World Encyclopedia, 2017, s.v. “The Seven Liberal Arts.” ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 237. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 235. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 237. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 237-238. ↵

- Stephen Duggan, A Student’s Textbook In The History of Education (D. Appleton-Century Company), 82. ↵

- Patrick Joseph McCormick, “History of Education: A Survey of the Development of Educational Theory and Practice in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Times,” The Catholic Education Press (Washington DC, 1953), 239. ↵

85 comments

Mark David Vinzens

„The term “liberal arts” comes from the Latin word “liber,” which means “to free”; thus it was believed that the Seven Liberal Arts would “free” one through the knowledge gained in each of various disciplines.“

Very true. The free mind is the goal of true education.

Amanda Shoemaker

I never knew that the liberal arts were of a Greek/Roman origin. It’s interesting how much of our modern day educational content came from the Greek/Romans. The author of the article was correct in the fact that I had never heard the phrase ‘Seven liberal arts’ before. I never knew that the church regarded education so highly during that time. It was very interesting to learn that you couldn’t be an ordained priest without the knowledge of the liberal arts.

Melissa Garza

I didn’t really pay attention to the difference between a liberal arts school was and not, so when learning about the liberal arts and the history behind this education, it was very interesting to me. I wasn’t aware that there were different divisions of the liberal arts such as the Trivium, the place where the three roads meet, and the Quadrivium, the place where the four roads meet.

Alondra Lozano

It never came to mind as to how our education really came to be. This was a very interesting article! What really got my attention was how they implemented music to the seven liberal arts and how it is still being used in our modern day education. It is impressive as to how they made the medieval trivium and quadrivium the core of our learning and how it has not changed.

Mia Hernandez

When choosing a college I didn’t really care if it was a liberal arts school or not, mostly because then I wasn’t so sure what that was. After reading this article and now knowing what the seven liberal arts are and how they are still incorporated into our education system, I can understand why so many people would want to be apart of a liberal arts school.

Sofia Almanzan

This is a really great article. When I was looking for schools to go to for college I really wanted to go to a liberal arts school because it makes you a well rounded person. This article was very informative in giving me information on the history of the kind of education I hope to get.

Sara Guerrero

I found it interesting that in medieval times the seven branches of knowledge were divided into two categories. It does a great job explaining what Trivium and Quadrivium is and it sort of reminds me of qualitative and quantitative. Also, they had Greek and Roman influences and I see that development that was obtained into creating the modern education system we have today.

Seth Roen

I never know how ancient the concept of liberal arts, and never knew that they are seven types of discipline. Also, never know that the word comes from Latin. It interesting how many of the fields of studies today is derived from the seven arts. The painting shows that it continued during the so-called “Dark Age” where learning was forbidden.

Zachary Kobs

It’s weird to think that a small group of men in (360 AD-428 AD) made the foundation for liberal arts to grow off of and that we still use it today, but it is modernized. The article says, “Greek philosophers believed the Liberal Arts were the studies that would develop both moral excellence and greater intellect for man,” and I agree. Although now, not everything revolves around religion within those disciplines for the seven liberal arts.

Dylan Hydock

It is interesting to know that when we think of liberal arts we think of it as a degree path in modern day and less of it being the core to learning. This standardization of advanced and in depth topics would eventually lead to higher level of education which would pave the way for the medieval renaissance, and ultimately lead to knew discoveries in sciences, art, and music.