“When I think of myself, I grieve,” Lady Dhuoda, November 30, 841.1

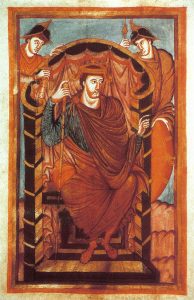

To understand Lady Dhuoda and her writings is to understand the circumstances of life around her. Kings and noblemen made decisions that would incidentally affect her life and her children’s lives. After the death of the Frankish king Charlemagne in 814, the next ruler in line was his son Louis the Pious. In the ruling years of Louis the Pious, he had four sons: Lothair I, Pippin I of Aquitaine, Louis the German, and Charles the Bald. As the sons grew, Louis the Pious appointed each son to a different territory to rule as a subordinate king.2 While they would rule the land appointed to them, they would ultimately still have to answer to their father, Louis the Pious. However, this division led to many revolts among the brothers against their father. Lothair and Pepin were the first two sons who revolted. Soon it would become brother against brother.3

The agreement from Louis the Pious to his sons was simply that Lothair would have the most land due to his being the oldest and, at the time of Louis the Pious’ death, he would be above his brothers. The second and third brothers, Pepin and Louis, would also be monarchs, but if they did not produce heirs, their land would go to Lothair. However, Louis the Pious took a second wife after his first wife’s passing, and had a fourth son named Charles. This angered the first three sons due to their father changing the contract between them all, due to their new half-brother.4 They believed that Charles should not be entitled to the titles or lands, due to being a half-brother.

With this, Emperor Louis the Pious trusted a few men of the court around him, one of those being Bernard of Septimania. Bernard was one of the men that proved his worth to the emperor. Bernard was granted land and different titles and quickly rose through the ranks within the court.5 His high status within the court only allowed his family to be used as pawns. His wife, Lady Dhuoda, would suffer the consequences of his actions. At the start of their marriage, her life was soon owned by Bernard and later by kings who used the emotional connections to her sons to control her husband’s actions. At the birth of her first son, William of Septimania, she understood the type of love only a mother could feel, which we will later witness in her writings.6

Lady Dhuoda’s husband, Bernard, over time grew closer to Louis the Pious, so much so that he was granted, which gave him custody of his youngest son, Charles the Bald.7 Bernard and Lady Dhuoda’s relationship was complicated because he was at court in Aachen and Lady Dhuoda lived in Uzes, France. Bernard, being granted camerarius and custody of Charles the Bald, grew closer to Louis the Pious’s wife, Empress Judith of Bavaria. The public questioned their relationship, and he felt it best for him to flee. By fleeing though, Bernard lost his right over the land he was granted. However, the following year, 831, Bernard attempted to reconcile his previous actions, but Louis the Pious denied the request to regain the previously lost position and titles. Therefore Bernard became angered by the refusal and changed his loyalties against the king and toward Louis’s sons.8

The beginning of Lady Dhuoda’s and Bernard’s story starts with their marriage. Because of her writings we know that the marriage between Lady Dhuoda and Bernard took place on Summer Saint John’s Day (June 24), 824. Two years later, Lady Dhuoda gave birth to her first son, William, on November 29, 826, and it was at this moment, she felt the love only a mother could feel. She believed William was “the most-desired firstborn,” given to her with God’s help.9 It has been known that Lady Dhuoda was a tremendously faithful follower of God and an avid reader of the scriptures. She kept her faith strong even in times of suffering.10

As newlyweds with a young child, Lady Dhuoda would accompany her husband, especially to essential events. However, while in Barcelona with Bernard, the city was invaded by Saracenic. Bernard, being a Count at the time, was able to regain Barcelona’s power without Frankish help, which impressed Emperor Louis the Pious. To reward Bernard, Louis the Pious allowed Bernard and his family to live at the palace of Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen), and then granted him the title and office of chamberlain, or camerarius.11 At first, Lady Dhuoda and her son William would travel and take residence with Bernard, but as the civil wars broke out between the royal brothers, it became harder to keep peace near them. Bernard’s constant changing of loyalties during his life towards Emperor Louis the Pious would cause devastating repercussions for Lady Dhuoda. Even after the moment of Louis the Pious’ death, consequences from previous actions would lead to Lady Dhuoda with heartache.

As stated, Charles the Bald, being the youngest brother from a different mother, gave room for his older brothers to become angry and question each heirs’ portion of inheritable land. Pippin had a son named Pippin II, who would inherit the land his father ruled.12 At the time of Louis the Pious’ death, Bernard was devastated and angry, knowing his loyalties were soon to be questioned by the late emperor’s son and grandson. Coincidently, soon after the death of Louis the Pious, Lady Dhuoda became pregnant with her second son, and gave birth in 841.13

Lady Dhuoda, at this time, had been living in Unez, West Francia. However, her eldest son, William, was now used as a pawn to prove his father’s loyalty to Charles the Bald. William was separated from Lady Dhouda and returned to Aix-la-Chapelle to guarantee Bernard’s loyalty toward Charles. William had not aged fifteen prior to this separation.14

The following heartbreak she suffered was eight months after the birth of her second son. Bernard was away in Aquitaine attempting to gain rights over Gothia and sent for the new baby. Bernard had the child christened and later named the child Bernard after himself. It is said that Lady Dhuoda never knew her second son’s name.15

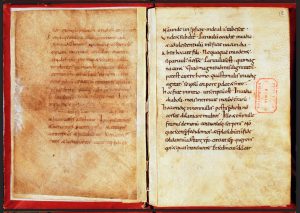

With these tragic heartbreaks that she endured from the separation not only from her husband but from her children, she took up the art of writing. She was insistent on leaving teachings for her sons to know how to be well-rounded, loving Christian men. While women during this time were rarely allowed formal instruction,Lady Dhuoda was one of the lucky few to receive a foundation of education, although it was not extensive.16 There is little known about her family. However, historians believe that she came from “well-to-do parents; she seceded a good education,” which is indicated through her writings and her familiarity with the Bible. Lady Dhuoda loved loving and praising God, which is shown through the writing of her life towards her eldest son.17

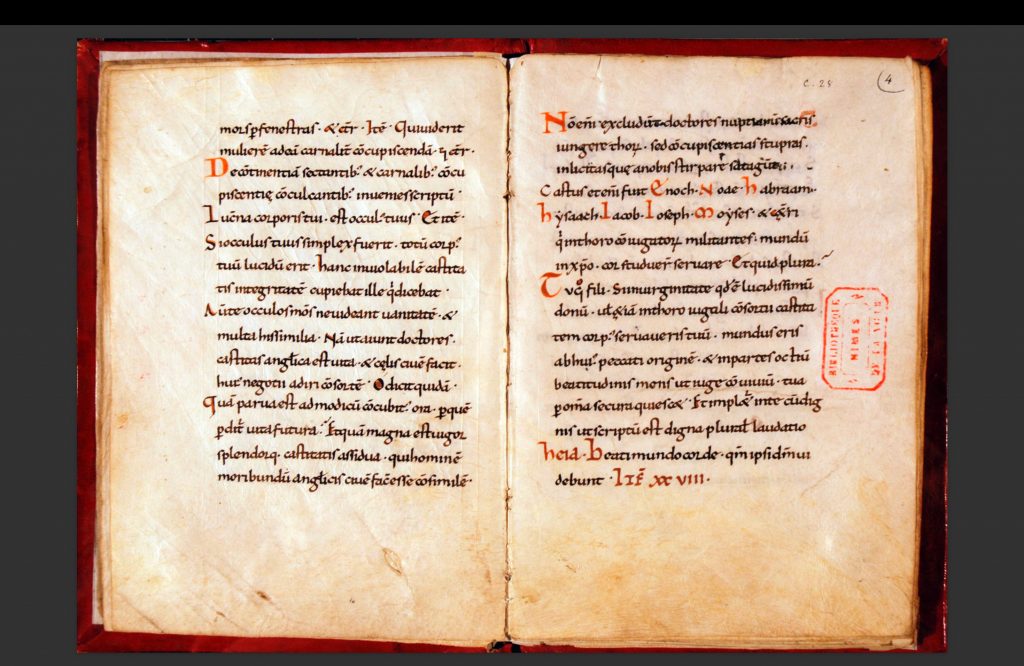

Lady Dhouda wrote a manual called Liber Manualis. It was a manual for her eldest son in hopes that it would provide insight into looking after his younger brother to teach, love, and guide him through his life. “First of all, he must learn that God should be loved, praised, and sought because of His Greatness and majesty, for He is above, below, within, without, the Ruler, Sustainer, Provider, and Protector. ‘I admonish you, my handsome and lovable William, to acquire many books wherein you may learn through the most holy Fathers all about God… Read the words of mine, too, and teach them to your little brother whose name I do not know.”18

She wrote about her favorite books of Psalms and Wisdom and remarked, “there is nothing in this mortal life in which we can linger more intimately than in the divine praises of the Psalter. No human being can by words or thought explained the virtues of the Psalms… For in them you will find the incarnation, passion, resurrection, and ascension of the Word of God… Throughout your entire life you will find in the book of Psalms alone matter for reading, study, and teaching; in it you will find the prophets, Gospels, apostolic letters, and all the volumes of divinity… you will discover therein prophesied the first and second Advents of the Lord, as well as His life and teachings. And through it, by God’s grace, you will come to the very marrow of profoundest understanding.”19

Lady Dhuoda’s goal was for her eldest son William to understand that while she was not near him, she would guide him with her understanding of God. She wanted him to frequently read her work whenever a question or barrier came into his life.20 She knew she had already taught him what his duty was for his mother’s sake but pressed on that “when I am gone; you will have this little book of teaching as a reminder: you will be able to look at me still as into a mirror, reading with me your mind and body praying to God. Then you will see clearly your duty to me.”21

She also wanted him to understand the subject of morality of the three theological virtues; faith, hope, and charity.22 She stated, “pray, my son, not only in church, but whenever you may be, and then in the name of God go forth to whatever service is required by your father Bernard or by your seigneur Charles.”23 She also wanted William to pray for “bishops and priest..and for his father, he should ask of God peace and concord,” including his uncle, Bernard’s brother, who took William away from her.24 She truly wanted him to learn and study God’s word, often repeating how important it was, “I urge you, William, my beautiful beloved son… learn something about God the creator. Implore Him, cherish Him, love Him…”25

By understanding the importance of true forgiveness by God, she wrote that William should be comfortable with being vulnerable with those who offer penance for sins. With this understanding of honesty and vulnerability with others, his conscience would not hold him back from the past mistake but only push him forward. “Make sincere confession to them in secret with sighing and tears… Commend your mind and body to them… For a true priest, by instructing you in school and in manly sports and by setting an example, will cause you to arrive at worthwhile advancement.”26 This could also help him become loved in court. With a love for others, he could become great: “love all, and you will be loved by all.. if you love them in the singular, they will love you in the plural. It is written in the Art of Grammar of the Donates, ‘I love you, and I am loved by you, I kiss you and am kissed by you (osculor te et osculor a te), I cherish you and am cherished by you, I know you and am known by you.'”27 She also stated that it was important that William showed respect for others: “therefore my son William… in all the changeable situations of the world… cherish and show respect to whatever one or many persons you wish to respect you.”28

Lady Dhuoda borrowed beliefs from not only Christians but from Jews. She ultimately wanted her eldest son William to know kindness and acceptance but importantly the love of God and how to love the way God did. She wrote eleven books for her son, each with a different use, from loving God, the Holy Trinity, moral life, the usefulness of the beatitudes, body, spirit, prayer, and her favorite book, Psalms. She tried to stop at book ten a total of three times. However, she would continue writing. Finally, by stating an end with the words “finunt versiculi…finita verba…finit liber…” only to continue writing shortly after.29 She dearly missed her son, and while he was not near her, she dearly wanted to ensure that he was safe due to the changing ways of the royal court. “It all seems much too far away from me, longing as I do to see the shape of your face…”30

Unfortunately, it is a mystery whether either of her sons read her writings. She wrote the last chapter in her manual on February 2, 843. Moreover, sadly “her most-beloved William died at Barcelona in 850, still carrying on his father’s feud with Charles the Bald” at 24. Her youngest son, Bernard, whom she had only known for eight months, died as a rebel in 872.31 Her husband, Bernard, was “captured as he retreated, and in early 844, he was executed for treason.”32 Lady Dhuoda only having two children in her life, the line of her family ended at her death.

- ALLEN CABANISS, The Woes Of Dhuoda or France First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 38. ↵

- Rutger Kramer, “Framing the Carolingian Reforms: The Early Years of Louis the Pious,” in Rethinking Authority in the Carolingian Empire (Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 31-58. ↵

- Sylvie Joye, “Carolingian Rulers and Marriage in the Age of Louis the Pious and His Sons,” in Gender and Historiography, ed. Janet L. Nelson, Susan Reynolds, and Susan M. Johns, Studies in the Earlier Middle Ages in Honour of Pauline Stafford (University of London Press, 2012), 101–14. ↵

- Roger Collins, Early Medieval Europe 300–1000 (Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), 318-300. ↵

- Roger Collins, Early Medieval Europe 300–1000 (Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), 318-300 ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 40. ↵

- Rutger Kramer, “Framing the Carolingian Reforms: The Early Years of Louis the Pious,” in Rethinking Authority in the Carolingian Empire (Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 31-58. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 43. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 39. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 39. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters, ” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 41. ↵

- Rutger Kramer, “Framing the Carolingian Reforms: The Early Years of Louis the Pious,” in Rethinking Authority in the Carolingian Empire (Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 31-58. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 45. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 38. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 45. ↵

- Valerie L. Garver, CONCLUSION: The Lifecycle of Aristocratic Women, in Women and Aristocratic Culture in the Carolingian World, 1st ed. (Cornell University Press, 2009), 269–82, https://www.jstor.org.blume.stmarytx.edu:2048/stable/10.7591/j.ctt7zjz4.12. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 39. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 47. ↵

- Anne Carson, “Dhuoda’s Mirror,” ed. Carol Neel and Dhuoda, The Threepenny Review, no. 81 (2000): 13–13. ↵

- Anne Carson, “Dhuoda’s Mirror,” ed. Carol Neel and Dhuoda, The Threepenny Review, no. 81 (2000): 13–13 ↵

- Anne Carson, “Dhuoda’s Mirror,” ed. Carol Neel and Dhuoda, The Threepenny Review, no. 81 (2000): 13–13 ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 47 ↵

- Anne Carson,”Dhuoda’s Mirror,” ed. Carol Neel and Dhuoda, The Threepenny Review, no. 81 (2000): 13–13 ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS,”The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 47. ↵

- Anne Carson, “Dhuoda’s Mirror,” ed. Carol Neel and Dhuoda, The Threepenny Review, no. 81 (2000): 13–13 ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 47. ↵

- Anne Carson, “Dhuoda’s Mirror,” ed. Carol Neel and Dhuoda, The Threepenny Review, no. 81 (2000): 13–13 ↵

- Anne Carson, “Dhuoda’s Mirror,” ed. Carol Neel and Dhuoda, The Threepenny Review, no. 81 (2000): 13–13. ↵

- Anne Carson, “Dhuoda’s Mirror,” ed. Carol Neel and Dhuoda, The Threepenny Review, no. 81 (2000): 13–13. ↵

- Anne Carson, “Dhuoda’s Mirror,” ed. Carol Neel and Dhuoda, The Threepenny Review, no. 81 (2000): 13–13. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 49. ↵

- ALLEN CABANISS, “The Woes Of Dhuoda or France’s First Woman of Letters,” The Mississippi Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1958): 49. ↵

12 comments

Muhammad Hammad Zafar

One of the inspiring articles. The story was amazing and interesting. The main thing is that how she remained strong and search for ways to maintain the formations of her child rather than being distant from her. The main thing that she taught them faith in God. To be honest, the images was one of the amazing Part of reading the story that is the ancient and old writings and no doubt a new and well written story.

Jose Luis Gamez, III

Great job in narrating the story of Lady Dhuoda. I had never heard of her and this article that you wrote was informative and well worth reading. You did an amazing job in narrating this article and really enjoyed the images you used. Congratulations on your nomination.

Briana Martinez

Victorianna, congratulations on your nomination! This was such an interesting article! I wasn’t familiar with Lady Dhouda before, but I learned so much through your writing. Her love as a mother was so apparent through her writing. It was incredible to see how her faith kept her so strong even through such heartbreak and tragedy. Amazing work!

Shecid Sanchez

Congratulations on your award nomination! this was such an interesting article to read you did an amazing job providing a great amount of details. Ive actually never heard of this story so you explained it very well. Again I want to congratulate you on your nomination and good luck !

Alyssa Leos

First of all I want to say congratulations on your article being nominated for an award. I personally never heard of Lady Dhuoda. Her story was very emotional for me. It’s very important that mothers show that they would do anything for their child. She was such an amazing mother. I love her idea of writing her book. Again congratulations on your article being nominated. Very well deserved!

Kayla Braxton-Young

It was such an excellent reading. Lady Duhoda was a name I was unfamiliar with, but I was moved to tears by her tale. How she perseveres and looks for a way to raise her children despite their distance from her is incredibly amazing. But it is also upsetting to observe how her voice seems to have been drowned out and that she now has no influence over what happens to her kids. I really like how you used the images in your post; they go nicely with the story.

Ana Barrientos

Congratulations on your nomination! I enjoyed reading your article. It was interesting to read how much Lady Dhouda loved her children and wanted to teach them great morals. She only wanted the best for them, and she also taught them to put their faith in God, I enjoyed the images you used as well. Overall, great job!

Jocelyn Elias

Congratulations on your nomination Victoria. I think it’s a really interesting article. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a mother writing a step-by-step book for her child so this is really interesting. I really like the visuals you had to offer for your storyboard I think that it ties really well with your article. I also really like your sources, I love that you actually included good and well-thought-out in-text citations. Great job!

Kelly Guadalupe Arevalo

Hello Victorianna. Congratulations on your nomination. It was such a great reading. I had not heard about lady Duhoda before, but I was deeply moved by her story. It is really inspiring how she manages to stay strong, and search for a way to continue the formation of her children despite them being far away from her. But it is also sad, how her voice seems to have been overshadowed and left her with no say in her children’s fate. Very nice article. Good job!

Vanessa Preciado

I love this article! Lady Dhouda is brilliant. To make a book for her children to follow while she can not not be there is just heart warming. And her faith in God just tops it off. This article was very interesting and I also like the images used.