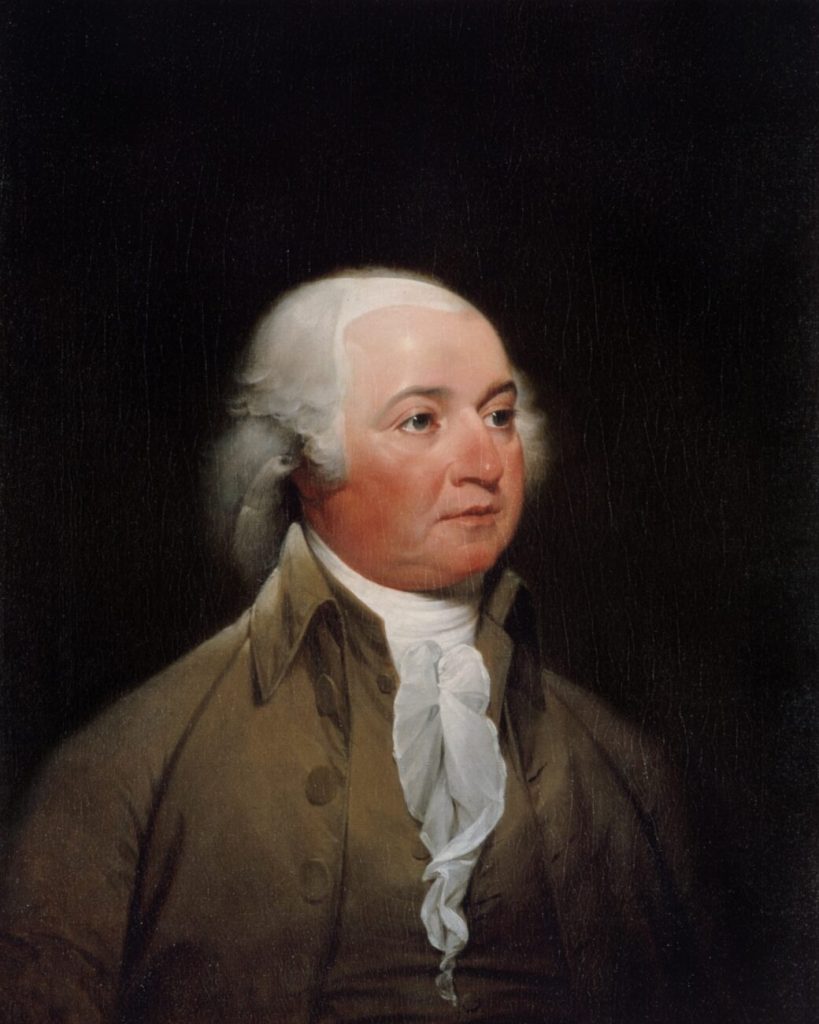

On a mild and partly cloudy spring day, in the House of Representatives chamber in Philadelphia’s Congress Hall, John Adams was sworn in as the second president of the United States. The date was Saturday, March 4th, 1797, and the time was 12:00 noon. Dressed in a plain gray suit, John Adams arrived in a simple fashion in hopes of not drawing any extra attention to himself. He stayed the night at the Francis Hotel and arrived by horse and carriage. The night before the ceremony, he was not able to sleep, with worry that he may not have the stamina to make it through his speech. His wife had spoken of the rigorous life you endure as a president, and she even wrote in a letter to her husband, John, saying, “The task of the president is very arduous, very perplexing, and very hazardous. I do not wonder Washington wished to retire from it, or rejoiced in seeing an old oak in his place.” Abigail knew her life would change forever when Adams became president.1

Now, before I tell you the story, it’s important to understand the campaign trail and some background on what led to the success John Adams saw in Congress Hall on this day, March 4th. The campaign trail was turbulent, but the results were narrowed down to two possible candidates: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Alexander Hamilton, whom Adams did not trust, was urging leading politicians to support Thomas Pinckney for President. Hamilton felt Pinckney was someone he could control. Thomas Jefferson doubted that Hamilton’s schemes would detour the outcome of Adams being selected as president. Alexander Hamilton was not popular with the popular opinion; he was a schemer, and Adams, as well as his wife, Abigail, disliked him greatly. Abigail wrote a letter to her husband John saying, “So, I have read his heart in his wicked eyes, the very devil is in them.”2

The Federalists favored John Adams, while the Democratic-Republicans supported Thomas Jefferson. The campaign was bitter on both sides. The violence of the French Revolution was blamed on the Democratic-Republicans. The Democratic-Republicans were accusing the Federalists of supporting monarchism. The Democratic- Republicans attempted to blame Adams for policies that were developed by fellow Federalist, Alexander Hamilton, under the Washington Administration. People of each party had their opinions of the candidate running for the opposing party. The Federalists and Federalist Press were labelling Jefferson as an atheist, as well as questioning his courage during the War of Independence. They also said he was a Francophile. Adams’ supporters blamed Jefferson for being pro-France. Meanwhile, the Democratic- Republicans were portraying John Adams as an Anglophile and monarchist. They believed he was secretly set on establishing a powerful family dynasty by having his son succeed him by becoming president. They believed he had ill intentions behind his running.3

The new constitution stipulated that the president was to be chosen by electors who were named by the state legislatures. Each elector was to name two choices for a president on one ballot.4 Though the final count would not be known until February, when the electors met, it was being said openly that Adams would become president. With electoral votes, the highest number of votes would elect the president, and the second highest number of votes would elect the vice president, even though the president and the vice president were from different political parties. The outcome of the election became official in February when Adams, who was president of the Senate at the time, read the final votes of the Electoral College. At the beginning of the election, there were five candidates: Aaron Burr, Thomas Pinckney, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Samuel Adams. Aaron Burr was the only candidate who chose to wage an active campaign. He travelled to every New England state and spoke with many presidential electors. However, even with Adams, Jefferson, and Pinckney never leaving home, their supporters campaigned energetically in hopes of their hero winning. These men embraced the political model by refusing to campaign.5 They believed that a man should not pursue office; instead, the office should seek out the man. They all thought that the most innovative and talented men should govern, but also that the ultimate power rested with the people.6 In the end, John Adams won the election by a small margin over Thomas Jefferson. John Adams had 71 votes, while Thomas Jefferson had 68. Thomas Pinckney followed behind Jefferson with 59 votes, Aaron Burr behind Pinckney with 30 votes, and lastly Samuel Adams, with 11 votes.7 John Adams took a very important step prior to his inauguration. He chose to keep George Washington’s 4 department heads and cabinet members, as he felt this was the surest way to preserve Federalist harmony. He knew that it would be very upsetting to replace them, as Washington had been the one to appoint them.

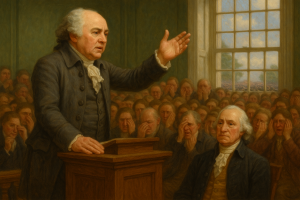

Oliver Ellsworth, who was the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, administered the oath of office. This was the first inaugural oath to ever be administered by a chief justice of the United States. It marked the first peaceful transfer of presidential power in the history of the young United States. Citizens gathered near Congress Hall, eager to witness a moment never seen before, a new president taking office without revolution or violence. There was not an empty seat to be found in the Philadelphia Congress Hall. However, his family was not able to attend, and this made him feel miserably alone.1 He was about to step into one of the most powerful roles in the world, following in the footsteps of George Washington.9

Inside Congress Hall, the chamber was filled with government officials, members of Congress, and a multitude of influential private citizens, all gathered to witness the first transfer of presidential power in U.S. history. As former president George Washington entered Congress Hall, there was a burst of applause. George Washington is the only president in history who has been elected unanimously. He received every vote from the public, not just once, but twice.10 He took a seat in the audience rather than being the center of attention. Washington was dressed in high fashion, wearing a black velvet suit. Adams’ rival, Thomas Jefferson, had just previously been inaugurated as Vice President that morning. Jefferson was also dressed in high fashion, as he wore a long blue frock coat. This would be the only time in history that a president and a vice president were from different political parties. John Adams was a Federalist, while Thomas Jefferson was a Democratic-Republican. While they did not agree on much, they both had a strong hatred for the press. The press was ruthless towards both men that morning, and followed them long after.11 We can assume that those present understood the historical weight of the moment. The peaceful change of leadership, in a time when most nations saw power shift only through bloodshed or royal ties, was seen as a victory for the young nation. Adams, aware of the significance of this day, approached the stand to deliver his inaugural address.9

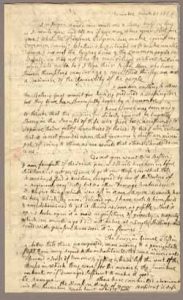

His address was delivered with great confidence and effect, as his voice was strong and steady. He spoke of our country’s victory in the American Revolution and the formation of our government, comprising 16 states, three of which had just been added. He also spoke of his beliefs in the equal rights of all states and in expanding education for all people. He was a big advocate for the preservation of freedom, as he praised American agriculture and manufacturing during his address. It is also noted that he spoke of his belief in the spirit of equity and humanity for American Indians.1 Although his wife, Abigail, was not present to hear him deliver his address, she knew what arduous hardships lay ahead. This was expressed in a letter she wrote to her husband on January 15, 1797. “The cold has been more severe than I can ever before recollect. It has frozen the ink in my pen as well as chilled the blood in my veins, but not the warmth of my affection for you, for whom my heart beats with unabated ardor through all the changes and vicissitudes of life, in the still calm of Peacefield, and the turbulent scenes in which you are about to engage.”14

Included in his speech on the clear, beautiful day of March fourth were his words about what he felt was the great threat to our nation. Those threats were the pestilence of foreign involvement, dissension within the country, and the spirit of the party. He was remembering the founding of our nation and made his promise to the American people that he and the Legislature would uphold the Constitution and serve the people. Adams also promised free and fair elections. To wrap up his speech, he gave a courteous tribute to the leadership of George Washington, then gave a prayer to our Supreme Being. He finished with exactly this: “With this great Example before me; with the Sense and Spirit, the Faith and Honour, the duty and Interest of the Same American People, pledged to Support the Constitution of the United States I entertain no doubt of its continuance, in all its Ennergy and my mind is prepared, without hesitation, to lay myself under the most solemn Obligations to Support it, to the Utmost of my Power. And may that Being, who is Supream over all, the Patron of order, the Fountain of Justice, and the Protector, in all Ages of the World, of virtuous Liberty, continue his Blessing, upon this Nation and its Government and give it all possible Success and duration, consistent with the Ends of his Providence.” John Adams then “energetically repeated” the oath of office, “seated himself, and after a pause, he rose and bowed to all around him and retired.”15 His speech was a total of two thousand three hundred and eight words and contains the longest sentence in inaugural speech history, at seven hundred and thirty-seven words.16 Much of the audience in Congress Hall was weeping, as they were so moved by his words and overcome by sadness at the fact that George Washington was leaving office. Washington, however, remained solemn and unclouded. Adams later wrote, “Me thought I heard him think, Ay! I am fairly out, and you are fairly in! See which one of us will be the happiest.”17 Though Adams stepped into a role shadowed by George Washington’s great legacy, his confident and steady presence, as well as his compelling words, assured the nation.

- David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 468. ↵

- John Patrick Diggins, John Adams (New York: Times Books, 2003), 86- 87. ↵

- James Taylor, “John Adams: Campaigns and Elections,” Miller Center, University of Virginia, accessed November 24, 2025, https://millercenter.org/president/adams/campaigns-and-elections. ↵

- David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 393-394. ↵

- HistoryNet Staff, “The First Real Two‑Party U.S. Presidential Election in 1796,” HistoryNet, December 16, 2015, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.historynet.com/the-first-real-two-party-us-presidential-election-in-1796/. ↵

- James Taylor, “John Adams: Campaigns and Elections,” Miller Center, University of by, accessed November 24, 2025, https://millercenter.org/president/adams/campaigns-and-elections. ↵

- David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 471. ↵

- David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 468. ↵

- U.S. National Park Service, “John Adams Inauguration,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/places/john-adams-inauguration.htm. ↵

- The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, “An Imperfect Election,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, accessed November 24, 2025, https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-first-president/election/imperfect-election. ↵

- David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 462-464. ↵

- U.S. National Park Service, “John Adams Inauguration,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/places/john-adams-inauguration.htm. ↵

- David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 468. ↵

- David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 466. ↵

- Philadelphia Gazette of the United States, 6 March; “No 11. Address of the President of the United States on the day of his Inauguration into office March 4th. 1797,” Records of the U.S. Senate, Presidential Messages to the 5th Congress, 1797–1799; Philadelphia Gazette, 6 March. ↵

- U.S. Senate, “Inaugural Addresses,” Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies, https://www.inaugural.senate.gov/inaugural-address/. ↵

- David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), p. 468-469. ↵