Winner of the Fall 2018 StMU History Media Award for

Best Article in the Category of “Gender Studies”

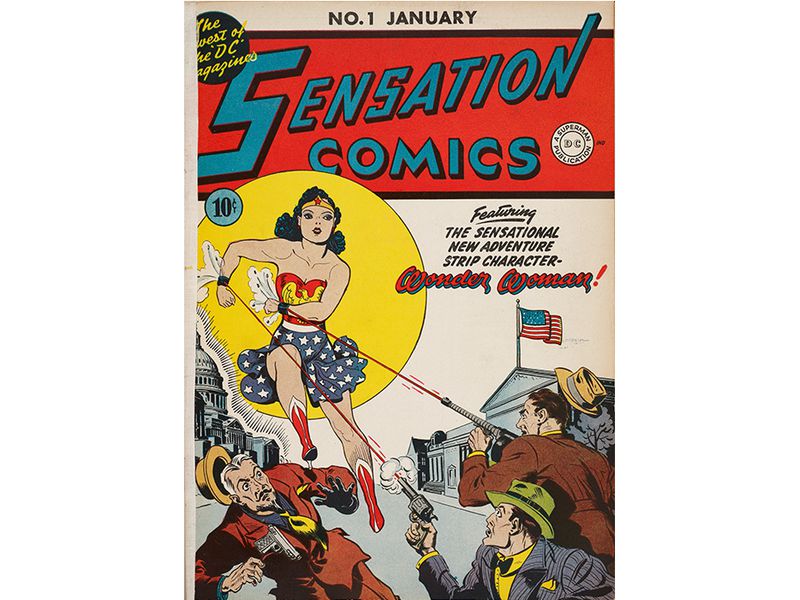

When conjuring an image of Wonder Woman, what is most prevalent? A beauty badass dispensing justice? A curvaceous sex symbol daring men to misbehave? Lose all the preconceived and media-induced notions of this Amazonian warrior, and the genesis of her tale will enthrall. The Wonder Woman character has been a superhero icon for seven decades, and has undergone numerous transformations and evolving backstories, and has been remolded to shape current times. At one juncture, she was even forced into compliance with newly imposed federal regulations. But who exactly was the original 1940’s Amazonian princess?

William Moulton Marston created America’s first female superhero, someone motivated by love rather than by personal tragedy. He used his original comics to send a message, through various themes and methods, of physical bondage. William Marston utilized bondage as a metaphor to represented the grip a male-dominated society held on women. Marston referred to the comic as brilliant “psychological feminist propaganda,” and with it, found a creative vehicle to spread his ideology to the masses.1 William Marston introduced mainstream America to physical bondage elements to accurately depict early twentieth-century gender disparities in three variations.

Bondage is the physical restraint of another person to enforce subjugation. This was demonstrated when men restrained Wonder Woman, when Wonder Woman restrained men, and in the rare occasions when Amazonian women restrained each other. Using these three illustrations, the comic demonstrated how women were only rendered helpless in life when bound down by men. Comparatively, when Wonder Woman bound the antagonistic evildoer, she did so to establish understanding of authority and to influence reformed behavior. Lastly, the bondage used between Amazonian women built trust, love, and mutual respect.2

William Moulton Marston’s outward image was as far from the traditional comic writers of his day as professionally possible. The Wonder Woman creator was not a mother’s basement-dwelling socially-inept young pulp writer or struggling artist. Marston was a three-time Harvard graduate and renowned Psychologist. He was an established professional, who was known as a lawyer, professor, researcher, and published author by the time he began writing the Wonder Woman comic at age forty-six.3 When it came to William Marston’s personal life, the abnormalities persisted. He lived in a polyamorous romantic relationship, sharing a household with two women. His wife Elizabeth Holloway was a successful lawyer, and his acknowledged lover, Olive Byrne, was a fellow psychologist. The three lived together as one family unit starting in the late 1920’s until William Marston’s death in 1947. Each woman gave birth to two of Marston’s children. They all came to a logistical arrangement that suited everyone. Elizabeth Holloway and William Marston continued their respective careers, while Olive Byrne stayed home and raised all four children. The two women continued to cohabitate until Olive’s death in 1985; Elizabeth died in 1993.4

Marston channeled his admiration for these two strong-willed women and drew creative inspiration from his unorthodox family. William Marston’s personal life reflected his convictions, and he quite adamantly believed that women were naturally far superior to men. Marston had deep-running personal ties to the American twentieth-century suffrage movement. His wife, Elizabeth Holloway, was denied acceptance to Harvard Law School, solely based on her gender. William Marston was also the de facto nephew-in-law of Margaret Sanger, infamous birth control advocate and women’s rights activist.5

To fully understand what Marston wanted to convey through his comic, it is imperative to understand the full scope of the man himself within both personal and professional realms. While he held particular views on non-monogamy and sexuality as a whole, the messages and ideals of the original Wonder Woman were utterly non-sexual. Instead, more profound meanings to the comic trail from his unique research into human behavior. He produced the DISC Theory, which stands for Dominance, Influence, Submission, and Compliance. These interlinked characteristics are the prevalent and intended themes throughout the original Wonder Woman comics.6

In 1928, he published Emotions of Normal People. In this book, Marston detailed his fascinating observations within the social interactions of personal behaviors. He concluded that harsh dominance leads to forced compliance, while gentle influence leads to willing submission. These insights are still incorporated as a template for personality assessments ninety years later.7

Generally, society expected men to be educated and employed, and expected women to be at home and raise children. Marston believed that women should not only govern themselves across all social planes, but he took it further and insisted that women were far superior to men and would rule the world within a hundred years. The women’s suffrage movements of the early twentieth century strongly impacted Marston. These women utilized images of women held in bondage chains to represent the lack of control they shared because of men’s oppressive restrictions. The injustice of men’s laws against the rule of a woman’s own body—and even mind—crushed a woman’s potential of being seen as a social equal. Marston purposefully carried these images and themes into his comics to spread his message to the masses.8

The most common physical bondage scenarios in his comics illustrated various male adversaries restraining Wonder Woman in some fashion; sometimes she would be chained to a laboratory table, or sometimes she would even be caged and dangling from the ceiling in order to drain her very soul. If a villain was able to steal Wonder Woman’s golden lasso, she was full-body bound with it, rendering her helpless and immobile, and all of her superpowers were null and void. To win the day, Wonder Woman called upon her fellow female friends, or single-handedly outsmarted the villain. Her actions were a direct correlation for the need of real women in the world not to settle nor accept social confines, but to rally together and overcome any masculine induced hardship. Independence was attainable only if women would fight for it. When men take what power belongs rightfully to women, women become helpless. Women must take control back from men and rise above the limits set for them.9

Arguably, Wonder Woman would not be a very capable superhero if she was incapable of catching the bad guy. The illustrated beauty in her methods was William Marston’s creative genius. Evildoers were helpless to resist Wonder Woman’s every command when he was bound by her golden lasso. She influenced their behavior, using love. She never harmed a villain more than necessary to subdue him, and it is important to point out that Wonder Woman never killed a foe, whether intentionally or circumstantially, as other superheroes sometimes did in the course of dispensing justice. Moreover, Wonder Woman uniquely spent time attempting to reason with her adversaries, imploring gentle logic to realize the error of their ways. Violence was not the only answer to correcting wrongs, and she always allowed her foes to be apprehended by police or military forces. William Marston was drawing parallels to his psychological research. He provided a female heroine who utilized influence to posture submission.10

The least commonly depicted physical bondage scenario is perhaps the most profound. In original Wonder Woman comics, The Pleasure Island, native Amazonian women would bind each other in various competitions and displays of admiration and respect. Wonder Woman would allow her companions to bind her with the most robust chains possible, both sides knowing she could effortlessly escape the restraints. Bondage games were played to strengthen the emotional bond they shared, which would establish and build trust between the women. Wonder Woman boasted that the strongest binds on the island could never hold her down and encouraged friends to try their hardest.11 William Marston was expressing how women should take their confines and rally those chains as a shared burden, unite together to fight against the social injustice. These bondage implementations were indicative of women’s untapped potential power.12

There are comic critics whose opposing views only recognize that William Marston tried to incorporate positive messages for women. Bradford Wright, author of Comic Book Nation, concluded that “there was a lot in these stories to suggest that Wonder Woman was not so much a pitch to ambitious girls as an object for male sexual fantasies and fetishes.”13 This opposition is marginalized by a distinction of the characters speaking directly to young women within the comic panels, sending strong messages of independence and highlighting the importance of education and self-reliance. Richard Reynolds, contributor in The Superhero Reader, calls William Marston’s feminist pretensions disingenuous and argues that the comic was actually “developed as a frank appeal to male fantasies of sexual domination.”14 This short-sighted over-generalization is negated by the depth to which Marston developed his female character. If the goal were male sexual ideology, Marston would not have gone to extreme lengths in character development. He would have left Wonder Woman as a shallow hero only serving to further a male character’s story growth. Instead, Wonder Woman seeks out justice, not personal admiration, fame, nor even general male acceptance.

In alliance with DISC theory and William Marston’s message, Ben Saunders, author of Do the Gods Wear Capes, interpreted that “men must learn from women the virtues of love and of submission. When they do, and when they rule, the millennium will arrive.”15

Since William Marston’s death in 1947, the image and icon of Wonder Woman have been continually distorted from the original intended meaning. Wonder Woman has been reduced to a modern model of sexual prowess and numerous references to sexual bondage themes that never originally existed. Marston spent six years sending the world a message, one that has now been adapted and remolded until the original intent is long lost. The original golden lasso would compel a captive to obey any command. Later versions downgraded the weapon into a “lasso of truth,” which only prevented the captive from lying to Wonder Woman. In the twilight years of his life, William Marston wanted to impart a specific message to all his readers about female superiority. The only hope for mankind was female. The original Wonder Woman comics were his way to posture young readers for this crucial gender revolution.16 William Marston’s works were his way of representing feminine strength in fiction and art to a society that would not admit that such a thing existed in real life.

- Jill Lepore, The Secret History of Wonder Woman (New York: Vintage,2015), front page. ↵

- Noah Berlatsky, Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017), 50-51. ↵

- Tim Hanley, Wonder Woman Unbound: The Curious History of the World’s Most Famous Heroine (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2014), 8-12. ↵

- Noah Berlatsky, Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017), 9-11. ↵

- Nick Joyce, Wonder Woman: A Psychologist’s Creation (American Psychology Association, 2008), 20. ↵

- Noah Berlatsky, Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017), 8. ↵

- William Moulton Marston, Emotions of Normal People (Kegan Paul Trench and Company, Limited, 1928), 405. ↵

- Jill Lepore, The Secret History of Wonder Woman (New York: Vintage, 2015), 1. ↵

- Tim Hanley, Wonder Woman Unbound: The Curious History of the World’s Most Famous Heroine (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2014), 53. ↵

- Tim Hanley, Wonder Woman Unbound: The Curious History of the World’s Most Famous Heroine (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2014), 21-22. ↵

- Noah Berlatsky, Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017), . ↵

- Tim Hanley, Wonder Woman Unbound: The Curious History of the World’s Most Famous Heroine (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2014), 11. ↵

- Bradford W. Wright, Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 21. ↵

- Charles Hatfield et al. eds., The Superhero Reader (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2013), 99-115. ↵

- Ben Saunders, Do the Gods Wear Capes?: Spirituality, Fantasy, and Superheroes (London: Bloomsbury Academic, an Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2016), 65. ↵

- Jill Lepore, “The Surprising Origin Story of Wonder Woman,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2014. ↵

150 comments

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. What a revolutionary comic Wonder Woman was when it first appeared. She represented hope for the future of women everywhere. It is interesting that the author held such unconventional views for his time. He subtly hinted at them in the Wonder Woman comic that he wrote. Women were superior in his eyes. I think that it is very admirable that he was an early advocate for women’s suffrage and education. His personal life also sounds like it was very interesting

Harashang Gajjar

During World War II, as Superman and Batman arose as mainstream pop symbols of strength and morality, the publisher that became DC Comics needed an antidote to what a Harvard psychologist called superhero comic books worst crime: bloodcurdling masculinity.Turns out that psychologist, William Moulton Marston, had a plan to combat such a crime in the star spangled form of a female warrior who could, time and again, escape the shackles of a man’s world of inflated pride and prejudice

Annissa Noblejas

As an interesting addition, neither Superman nor Batman ever directly endorsed, defended, or participated in the war efforts in any of their 1940’s comic strips. Where as Wonder Woman in several different story lines did just that. She captured spies, saved an American pilot, and foiled Nazi plots. In one particular comic, she even encouraged women to join the auxiliary forces and help their county in all manors of war efforts on the home front.

Ysenia Rodriguez

The differences between the original Wonder Woman and the more recent adaptations are much bigger than I initially suspected. As the article depicts William Marston’s inspirations and ideas for the character of Wonder Woman, she has only become a bigger symbol of female empowerment in my eyes. It’s very interesting when artists and writers use the events and people in their lives as motivation when creating their work. This was a great and very well-written article.

Lyzette Flores

Wonder Woman has always been a superhero I’ve been well aware of but I had never known the story behind her creation. Moulton Marston was a man that had great beliefs. He knew that women were not appreciated at all and wanted to do something about it. His comics made his beliefs come true in a way. It is sad to know that Wonder Woman’s initial creation has been modified to different versions. I hope one day it goes back to its original version because it has a beautiful and meaningful message.

William Rittenhouse

This was a very interesting article to read. I knew Wonder Woman did have ties to femenistic values, but not to this depth. This is a similiar motive as the Rosie the Riveter picture. Woman had much more of a family oriented stay at home role all throughout the history of the U.S. up until the end of the 20th century. I agree with the message that says woman can do most things men can, but some jobs aren’t made for women. An example could be U.S. special forces. Also femenism is a great thing as long as it doesn’t demonize men. Yes women should be treated the same and have all the same oppurtunities as men, but should at the same time not put men down.

Rosa Castillo

I appreciated the author’s message in this article. Wonder Woman Is truly an inspiring woman who has been a symbol of feminism and strength. She has served as a model for women all around the world. I am glad this article highlights William Marston’s purpose for creating Wonder Woman and the underlying message she represents.

Greyson Addicott

Much like the creator and mastermind of the hit 50’s TV show “The Twilight Zone,” the creator of “Wonder Woman” had a secret motive behind his art. Marston could not have found a better medium to both express his anger at the society that he lived in, while also encouraging the feminist movement around the nation. Regardless of the implications of the movement itself, it cannot be easily denied, that Marston had at least a strong impact on the American view of women. The article was superb, and it detailed the evolution of ideas behind “Wonder Woman” with unprecedented clarity.

Steven Hale

I have not seen the comics, but from the excerpts here, especially the picture with the Queen, it seems like the comics had at least some positive messages. My only knowledge of Wonder Woman was from the recently released movie, which I think had some similar themes to the comics, like Wonder Woman being inspired by love rather than tragedy, even if the storyline differed from Marston’s original vision.

Aneesa Zubair

I’m not that familiar with comics, but like most people, I can recognize Wonder Woman because she’s such an iconic character. It surprised me to see how much the character changed after Marston’s death; for instance, how the gold lasso was downgraded to give Wonder Woman less power. Marston clearly believed that women were important and even superior, yet forced into an inferior role by men. Modern-day audiences don’t always see this because so many aspects of Wonder Woman changed after Marston’s death. Learning about the ideas that inspired him to create the character helps us to appreciate her more. You did a great job researching and writing this article!

Jasmine Rocha

The article was written well and very informative. I was able to learn how the message of my favorite female superhero was originally a message and symbol of strength and empowerment of women. But the image and meaning behind Wonder Woman had changed over time due to the change in the times. I believe that we can bring Wonder Woman back to her old glory but using the resources of today world to bring back the intention of having her to empower women.