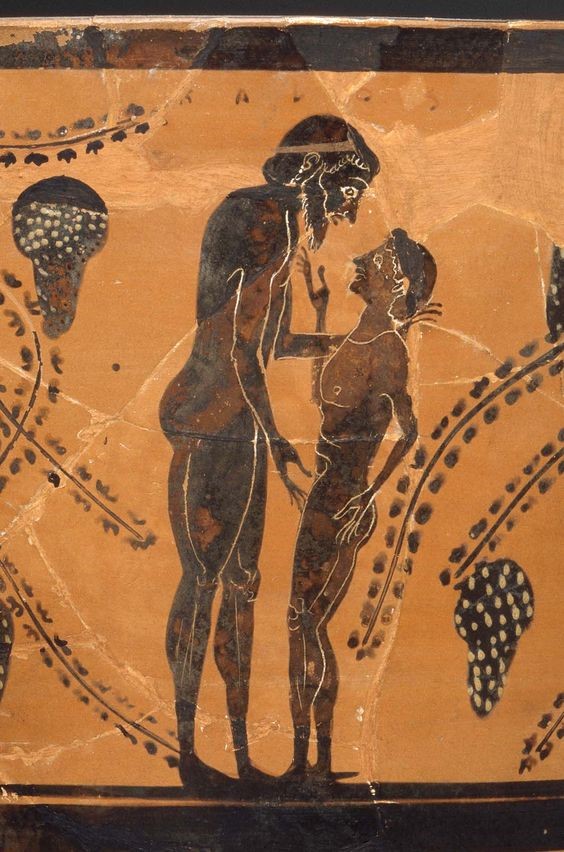

Before you read further, take a moment to set aside your preconceived beliefs about relationships and sexuality. As you read, aim to view historical practices through a purely objective lens. Imagine you are in another time, where the same definitions of words and beliefs simply do not yet exist. Now that you have checked your biases, we will examine the controversial (by today’s standards) practice of pederasty by ancient Greeks. Pederasty was a social custom in which an adult male would court a young Greek boy to become his model, guide, and initiator, and would become responsible for the evolution of his chosen young counterpart.1 Pederasty has become so associated with the modern concept of pedophilia that it is hard to discuss it without venturing into the taboo. It wasn’t until 1978, when K. J. Dover wrote the book Greek Sexuality, that anyone was willing to take a deeper and objective look at this practice.2

Although we cannot condone such a practice in modern times, pederasty was a normal and necessary part of Greek education for young men at a time when formal education did not really exist.3 To be objective, we must emulate Dover’s approach and step back from our current ideals and societal norms, to look at pederasty from the perspectives of the Greeks themselves, if we are truly to understand this cultural phenomenon and anthropological fact.4 From the Greek’s perspective, pederasty was not pedophilia, but an important part of growing up in classical Greece, and in the context of Greek culture it was not believed to be harmful or damaging to the boys involved.5 If anything, it was the normal path that nearly all young Greek men followed.

To fully understand the impact this practice had on Greek society, we must look at it from the point of view of the Greeks themselves, and this starts with analyzing their views on sexuality in general. Scholars make clear that ancient Greeks did not think of sexuality the same way that we do today. The closest word they had to describe sexuality was ta aphrodisia: “the matters of Aphrodite.” Aphrodite was the goddess of love in ancient Greek culture. Matters ascribed to Aphrodite encompassed sexual acts, urges, and pleasures.6 The key thing to understand about aphrodisia in ancient Greek culture was the fundamental distinction between the people in the relationship. There was always an active dominant partner and a passive submissive one. The Greeks never conceived of sex as a mutually satisfying experience shared by equal partners as we do today. They regarded sex as an activity one does by oneself, even though the other person is there to be acted upon.

This concept of dominant and submissive fits within the boundaries of pederasty, as the older man was the active partner while the youth was the submissive one. To the Greeks, the act of love was utterly one-sided: you could be longed for and loved, even desired, but there was no mutual love, meaning that both individuals could not love or desire each other.7 This helps us understand the reason the Greek relationship required one submissive and one dominant partner—love was only one sided. Robin Osborne, who wrote Greek History, states that in ancient Greek society “they worked to regulate their aphrodisiac and sensual pleasures, with their mind and body, but sexual activity was not treated as a matter of morality as it often is today.” The Greeks also differentiated sharply between eros, an erotic desire, and philia, the non-sexual affection family members or friends might feel for one another.8

This is not to say that all pederastic relationships were sexual though. The eromenos, the young beloved one, was expected to pay attention to the distinction between honor and shame throughout this relationship. The relationship was a preparation for manhood, and the eromenos was being evaluated by onlookers for his potential to assume domestic and civic responsibilities. It was considered a prime display of self-control for the older male to temper his passion and not engage in sexual intercourse with his progeny.

The dominant partner’s abstaining from sex was done out of respect for the boy’s civic status and personal autonomy. In Socrates’ banquet conversations, he voices a common assumption: “A youth does not share in the pleasures of sex with the man, as a woman does, but soberly looks upon the other drunk with passion.” The eromenos complied only with his lover’s requests out of esteem, gratitude, and the anticipation of a lifelong friendship.9 Thus, not all pederastic relationships were sexual.

Just as the ancient Greeks had very different definitions and beliefs surrounding sexuality, homosexuality also had a very different meaning than it does today. There is nothing that truly translates to our modern understanding of homosexuality. In ancient times, homosexuality was not defined merely by the sharing of a relationship between two partners of the same sex, but in doing so it violated the dominant/submissive construct. Had a Greek man sought a relationship with another man his age, he would be reviled for violating beliefs about normal Greek sexuality, yet a relationship with a younger, submissive man was viewed as normal and necessary.10 Homosexuality between same sex people near in age was not openly practiced in Greek culture. In fact, it was considered perverted. Greeks believed that homosexuality existed in the act of violating the dominant/submissive construct, not in the gender of the partner as later cultures defined the concept. Ultimately, beliefs and practices surrounding Greek sexuality in ancient times were different from anything existing in modern society, including a very different understanding of homosexuality.

Now, armed with this basic knowledge about Greek sexuality, we can better assess the value of the practice of pederasty from the ancient Greek perspective. The term pederasty derives from the Greek term paiderastia, which translates to “love of boys.”11 The practice of pederasty was first institutionalized in Crete, then moved outward to the wider Greek world. Pederasty took a strong hold in Sparta, where it was well suited to their warrior-based society, then spread from there to Athens. Professor and historian William Armstrong argues that Athens rose to grandeur only after it institutionalized pederasty. It provided a consistent method to ensure the education and development of young men in ancient times.12

To the ancient Greeks, pederasty was a respectable custom. It involved neither violent rape nor the use of a submissive slave, but the ardent courting of a free boy.13 There is much debate among scholars about the age of the youths when the courting began. Professor James Davidson writes in his book The Greeks and Greek Love that the Greeks placed an emphasis on the courting process for young men not starting until they hit puberty, and that puberty itself arrived later in antiquity than it does in the modern Western world. On the other hand, Marilyn Skinner, professor of gender and sexuality, argues that it most likely started at or around the age of fourteen for young men.14 Regardless, once they reached puberty, the courting process began.

The courting process was like the one undertaken by men seeking a young bride at that time. The older male would court the youth by flattering him with gifts. This would continue until he eventually won the young man over and claimed him as his beloved. But the boy could accept, or wait for another.15 This process occurred with both young girls and boys after entering puberty. Pederasty was viewed as the masculine analogue to marriage, the rite of passage that Greek girls of the same age were subjected to as well.16 Ultimately, pederasty was a passing stage in which the adolescent was the beloved of an older male, and remained as such until he reached a certain developmental threshold. After reaching that threshold, the young man would in turn take on an adolescent beloved of his own. The pederastic relationship was a part of transitioning to full adulthood and citizenship.17

Once a pederastic relationship was established, the older male had the responsibility of being the boy’s teacher and protector, and to serve as a model of courage, virtue, and wisdom.18 The older Greek male was referred to as the erastes, which translates to lover, while the youth was the eromenos, the beloved. Although these translations use words such as lover and beloved, they do not translate to love as we know it today, with mutual desire, shared affection, and equal satisfaction.19 Again, this practice was based on the dominant/submissive construct with the view that love was only one-sided.

There are those who categorize the act of pederasty in ancient Greece as simple pedophilia and an act of abuse towards the younger males involved. Comparative literature professor Enid Bloch is a loud critic of the practice and argues that pederasty involved the unjust exploitation of a trusting or helpless victim by someone in a position of power.20 Though we can certainly debate the harm to both young male and female Greeks from being courted at such young ages, the problem with Bloch’s argument is that she is comparing ancient Greek activities to our modern moral code to make her argument. Even if we agree that such a practice has no place in modern society, that does not mean that ancient practices should be judged using our current standards.

It is interesting how much attention the pederastic relationship between males gets from a moral perspective, as opposed to the attention we give to the practice of marrying off and impregnating young women. It is widely known that throughout history and extending into modern times, girls as young as twelve were married off to men much older than them. This is a practice that extends well beyond Greek society to just about every culture at different times. Yet we seem more able to accept that practice of taking young brides, without the moral outrage that exists with the pederastic relationship. Though we generally agree that the practice of taking young girls is wrong today, it is not viewed with the same level of disgust as the taking of young boys by older men. This dichotomy in and of itself suggests that we are viewing these relationships through our own culturally-informed lens. How can one practice be accepted as an unfavorable, but historically appropriate, practice, and the other not? This further demonstrates that although we tend to condemn historical practices such as pederasty, we have to look past our condemnation and seek to understand the cultural significance of these acts.

Instead we must look at the practice of pederasty through a historical lens and take into consideration the cultural factors within Greece at the time these events were taking place.21 What did pederasty mean to the Greeks themselves? To determine this, we need to establish the limits imposed by the modern definitions of the two key terms ascribed to such relationships. First, pedophilia as defined by Oxford dictionary means “sexual feelings directed towards children.”22 By arguing from the assumption that the same definition can be applied to ancient times as many critical scholars do, the immediate issue posed is that childhood was not defined the same as it is today. To the extent there was any comparison to be made between ancient and modern children, one thing is certain—”becoming an adult” occurred much sooner than age eighteen. Childhood for ancient children typically ended when puberty began. This would suggest that at the age when courting began, the young Greeks were considered adults by ancient standards. Therefore, the term pedophilia simply does not fit this situation.

Next, though the English word “pederasty” in present-day usage usually implies the abuse of minors, Greek law recognized the necessity of consent to enter a relationship, but not the reaching of a certain age as a factor in regulating sexual behavior.23 Robin Osborn, a classical historian, has pointed out that paiderastia gets complicated when we apply our twenty-first-century moral standards to it. She states that: “It is the historian’s job to draw attention to the personal, social, political, and indeed moral issues behind the literary and artistic representations of the Greek world. The historian’s job is to present pederasty and all, to make sure that we come face to face with the way the glory that was Greece was part of a world in which many of our core values are challenged rather than reinforced.”24 As stated before, in Greek society once a boy reached puberty, he was considered a self-sufficient citizen who was able to make rational decisions about sex, dignity, and honor.

Stripped of the limitations of these modern definitions, it is not hard to see why some scholars believe that the practice of pederasty was not as predatory as it seems by modern day standards. Anthropologist and author Geoffrey Gorer judged this relationship model as socially viable for the time, and stated “it likely did not give rise to psychological discomfort or neuroses for most if not all the young males involved because it was a common practice of the time.”25 Gorer’s views are in sharp contrast to Enid Bloch, who argues that Greek pederasty was psychologically and physically damaging to the boys involved. Enid Bloch even goes so far as to accuse fellow historian Mark Golden—who wrote the book, Children and Childhood in Classical Athens—of aiding in the exploitation of children today when he defends pederasty that took place in ancient Greece. She argues that Mark Golden would most likely condemn that practice within our society today, but accepts pederasty as the Greek way of acculturating boys to their future citizenship roles.26

There are undoubtedly strong emotions guiding many historians in their study of ancient practices. Some of them are certainly primitive from our vantage point. Yet, arguing that an ancient practice held an acceptable place in its historical context is not the same as endorsing that practice in the modern-day world. Enid Bloch’s attack of Mark Golden distracts from the merits of the practice of pederasty by suggesting anyone who believes it served an ancient purpose is a modern monster. Mark Golden simply argued that this was the Greek way of acculturating boys to their future citizenship roles. And, in fact, this is what pederasty was for ancient Greeks. It helped provide Greek youths the tools they needed to become successful Greek citizens. Golden was clear that if this were taking place in our society today, he would condemn it. Rather, we should recognize that Mark Golden’s example shows us perfectly how to remove ourselves from the modern context and immerse ourselves in a historical perspective.27

Furthermore, philosopher Miranda Fricker elaborates on taboo subjects in history by theorizing: “The proper standards by which to judge people are the best standards that were available at the time.”28 Simply put, we cannot and should not blame people for failing to be moral pioneers. The act of pederasty was an integral part of society in ancient Greece and at that time they saw the practice as a pivotal moment in the maturing of young men. Greek men courted their younger Greek counterparts just as they were entering adulthood by ancient standards. Once a match was made, the older man became the teacher, protector, and model of courage, virtue, and wisdom for the young man on his path through early adulthood. We cannot fit the pederastic relationship within our modern beliefs about sexuality, pedophilia, or even our current definition of pederasty. Moreover, we should challenge our discomfort with this practice with our discomfort with the same practice for young girls at that time. The very fact that the pederastic relationship is so much more controversial today reveals something about our own sensibilities. One thing is certain; we can safely assume that current and future generations of people will look back at views and practices we still consider to be morally appropriate with disdain for our lack of moral courage. The marching forward of time and the progression of our species all but guarantees that our moral standards will—and frankly should be—ever evolving. Let us not judge our predecessors so harshly, but understand and learn from them.

- Anton Adamut, “Philosophical Aspects of Homosexuality in Ancient Greek,” Annals of Philosophy, Social and Human Disciplines Vol 2 (2011): 14. ↵

- Enid Bloch, “Sex between Men and Boys in Classical Greece: Was It Education for Citizenship or Child Abuse?,” Journal of Men’s Studies 9, no. 2 (2001): 184. ↵

- Anton Adamut, “Philosophical Aspects of Homosexuality in Ancient Greek,” Annals of Philosophy, Social and Human Disciplines Vol 2 (2011): 14. ↵

- Marilyn B. Skinner, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture 2nd edition (United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 14. ↵

- James Davidson, The Greeks And Greek Love (New York: Random House, 2007), 72. ↵

- Marilyn B. Skinner, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture 2nd edition (United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 12. ↵

- James Davidson, The Greeks And Greek Love (New York: Random House, 2007), 19. ↵

- Robin Osborne, Greek History (London: Routledge, 2004), 24. ↵

- Marilyn B. Skinner, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture 2nd edition (United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 16-18. ↵

- Chloe Taylor, The Routledge Guidebook to Foucault’s The History of Sexuality (New York: Routledge, 2017), 217. ↵

- James Davidson, The Greeks And Greek Love (New York: Random House, 2007), 32. ↵

- William Armstrong Percy III, Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece (Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 47. ↵

- Enid Bloch, “Sex between Men and Boys in Classical Greece: Was It Education for Citizenship or Child Abuse?,” Journal of Men’s Studies 9, no. 2 ( 2001): 186. ↵

- Marilyn B. Skinner, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture 2nd edition (United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 21. ↵

- Enid Bloch, “Sex between Men and Boys in Classical Greece: Was It Education for Citizenship or Child Abuse?,” Journal of Men’s Studies 9, no. 2 ( 2001): 186. ↵

- Robin Osborne, Greek History (London: Routledge, 2004), 14. ↵

- Marilyn B. Skinner, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture 2nd edition (United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 15. ↵

- James Davidson, The Greeks And Greek Love (New York: Random House, 2007), 40. ↵

- Enid Bloch, “Sex between Men and Boys in Classical Greece: Was It Education for Citizenship or Child Abuse?,” Journal of Men’s Studies 9, no. 2 ( 2001): 186. ↵

- Enid Bloch, “Sex between Men and Boys in Classical Greece: Was It Education for Citizenship or Child Abuse?,” Journal of Men’s Studies 9, no. 2 ( 2001): 193. ↵

- Marilyn B. Skinner, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture 2nd edition (United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 15. ↵

- English Oxford Dictionary, 2017, s.v. “Pedophilia.” ↵

- James Davidson, The Greeks And Greek Love (New York: Random House, 2007), 89. ↵

- Robin Osborne, Greek History (London: Routledge, 2004), 72. ↵

- Marilyn B. Skinner, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture 2nd edition (United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 15. ↵

- Enid Bloch, “Sex between Men and Boys in Classical Greece: Was It Education for Citizenship or Child Abuse?,” Journal of Men’s Studies 9, no. 2 ( 2001): 188-190. ↵

- Enid Bloch, “Sex between Men and Boys in Classical Greece: Was It Education for Citizenship or Child Abuse?,” Journal of Men’s Studies 9, no. 2 ( 2001): 183-187. ↵

- Miranda Fricker, “Should we judge people of past eras for moral failings?” Matthew Sweet, The Philosopher’s Arm, August 2013. ↵

55 comments

Hector Garcia

I have to admit that at first, the idea of pederasty gave me chills. It is interesting how the author about to see the idea of pederasty from a historical point of view and how she was able to give a historical analysis rather than a personal one. This article was able to give a concise and had an objective point of view of the idea of pederasty in ancient Greece. I have to say that this essay is by far, one of the best-written essays I have read.

Kayla Lopez

This was a very interesting topic that really opened my eyes to just how much practices in the past are so different from what they are today. Though this is still a semi disturbing practice for me to comprehend, I agree that we can’t judge the ancient Greeks using our modern standards because they clearly did not have our same ideals and beliefs.

Isaac Saenz

I applaud the author for their decision to write about a controversial topic such as this one despite how many readers might disapprove. It is important to talk about all aspects of history as it offers insight on how human beings used to think and behave. Different eras in time are linked with different values and different traditions that others in the past or future might not understand. Nevertheless, as time goes on, culture and ethics age along with it. Overall, this was a great article that taught me something new about the mythical age of Greece.

Monica Avila

This article intrigued me by asking me to put aside my bias which was very hard to do. From reading that the Greeks saw sex as one-sides to the courting of young people by older individuals just disturbed me. Yes it was a different time with different views, but it is crazy to know how different we see topic like this in today’s society. Also the fact that it was seen as entry into manhood was really interesting to wrap my head around. The Greeks were fascinating but this particular part of their identity is really disturbing to me as a reader.

Andrew Dominguez

This article makes you really think about the world we live in and how certain thoughts have changed through out history. I knew of this relationship before this article, yet I’m still shocked on people would prey on the young. Even those this was taboo, the mentor would teach the kids lessons that could be applied to life. Instead of the lover thing they had, we should adopt kids having mentors to learn blue collar traits which can be applied to the world.

Joshua Castro

This article was one that was just rich in thought and perspective! I loved how you took into consideration the different viewpoints that have evolved throughout history and different cultures. By reading this article completely unbiased it lead to a deeper understanding of the Greek culture. It was very interesting to learn how they perceived love compared to how love is seen today. This was an extremely well articulated article on a controversial topic!

History Is Interesting

Bravo! Well written! I love how you emphasize that we must not let our modern bias and opinions get in the way of the objective study of history. As you said, what is moral today, may be immoral tomorrow. Different mindsets work in different cultures. In ours, a pedrastic relationship would be exploitative, but to an ancient Greek boy, it is normal, and would not hurt the psyche since sex and sexuality was viewed differently. We take for granted that our views of sex and sexuality, like many other things, are cultural, we only feel like they’re fundamental.

https://historyisfascinating.wordpress.com/

Hanadi Sonouper

To start of, I would give such high and positive remarks to the author for choosing such a specific and well articulated topic that would almost never be brought upon or discusses. The use of syntax and diction was used very well, that helped the reader understand the Greek understatement of homosexuality. Being a first time reader of this particular story had me very intrigued, that we think about present day sexuality and ideas, actually goes back thousands of years. To read about the Greeks love and relationship approaches was interesting, because not only did they have a different view of love, that is not necessarily wrong, but they believed strongly that this was how love is to be perceived. It certainly makes you think about the ongoing evolution of love since the beginning of time, and how it has been adapted and translated through different cultures.

Auroara-Juhl Nikkels

This article has been one of my favorite to read so far. I loved how you started your article with trying to make sure we read the rest of it with an unbiased perspective. I am a fairly open person, willing to try to understand reasons behind peoples actions. I think the society we live in today is fairly close-minded. I was surprised to read about the dominant and submissive relationships and it took me a second of re-reading and thinking to understand that the type of relation the Greeks had is probably very different from the version of dominant and submissive relationships there are now-a-days.

Natalie Childs

This article was incredibly well written and the author did a phenomenal job of being an unbiased historian. Ancient practices have always interested me, and when I stumbled upon this one, my interest was immediately piqued. While this would very obviously be a condemned practice today, it genuinely seems as though it was something that worked for the time. Something that we sometimes forget, as the author mentioned, is times were very different. People matured later, and people died sooner, so the idea of life span is completely different than what our construct of a lifetime is. Also, I found it incredibly interesting the point that it was more or less consensual, because of the ability to refuse and wait for someone else. With this said, we need to keep in mind that even today, there are states in the US that have consent laws as low as 14, so it can be said to be the same thing. I will definitely be reading more of this author.