In the early hours of August 24, 1572, all was calm in France until an unexpected chaos struck the Protestant Huguenots gathered at the Louvre Palace in Paris. After attending the wedding festivities between the Protestant Prince Henry of Navarre and the Catholic Margaret of Valois, the Huguenots were resting when a Catholic mob begin to attack those around the palace. The Catholics had planned an attack on the Huguenots, slaughtering as many as they could. Thousands of bodies covered the streets of Paris, and it became painted in red by the execution of the Huguenots. And the slaughter soon spread to nearby towns and cities. This attack on French Protestants by their Catholic countrymen was one of the worst in the age of European religious civil wars. How exactly did this come about?

During the mid-sixteenth century, the Reformation movement had spread from its origins in Lutheran Germany, finally reaching France; and it brought with it violent clashes between France’s Catholic population and its converts to Protestantism known as Huguenots. By 1570, there were Huguenots communities throughout France, and they were subject to numerous rounds of attacks by their Catholic countrymen in a series of religious civil wars, the last of which came to a temporary end with the Peace of Saint Germain in August of 1570. While neither religion had gained the upper hand over the other, both wanted to end the violence. Yet a conflict over whose religion would dominate France persisted between the two religions. The Huguenots, following the teachings of John Calvin, believed that they were the ‘elect’ and were predestined to be saved. The Catholics, who followed Catholicism, were led by the Guise family, who believed that the Huguenots were heretics that should be exterminated.1 The Guise family was a powerful and loyal support for the Catholic church in France. The main purpose of the Guise family was to conserve the Catholic faith and be the dominant religion in France. The Peace of Saint Germain was opposed by the Guise family, who had had nothing to do with the treaty, but who wouldn’t have hesitated to support it, if they had known that it was a trap to get rid of the Huguenots in Paris.2

The St Germain treaty granted the Huguenots control of a number of fortified towns and the right to hold public office, but not including public office in Paris or in the Royal Court. It also led to Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, leader of the Huguenot movement, to be appointed as a member of the King’s council.3 In order to bring about a peace between the two religions, as part of the settlement in the Peace of Saint Germain, Queen Catherine de Medici arranged the marriage between her daughter, Margaret of Valois and the Protestant Henry of Navarre on August 18, 1572. Religious tensions yet remained high, violence continued to flare up between the Catholics and the Protestants, and religious rioting continued to be widespread. Despite the tensions, the union of Margaret and Henry was intended as a reconciliation between the Catholics and Huguenots.4

The plotted assassination of the French Protestants could have been the arrangement of Catherine de Medici. The Queen, continuing to want power over France, decided she would keep a close eye on the Huguenot leader Coligny and his followers, to make sure things were going the way she desired. This is the reason why she arranged the marriage between her daughter to Protestant Henry, who was in line to become a future king of France. But it all backfired with the appointment of Admiral Coligny to her son’s, King Charles IX, council. Coligny’s appointment led to a flourishing relationship between the two men, which was something that the Queen had not planned on.

During his time on the council, the Protestant Dutch were currently under control of Catholic King Philip II of Spain. The admiral wanted to intervene and help the Dutch forces become free of the Spanish, and he received the support of King Charles to aid William of Orange, the leader of the Dutch revolt, to attack Spanish forces in the Netherlands. The Queen did not want to go to war with Catholic Spain, toward which the admiral seemed to be leading them.5 Starting to consider Coligny dangerous, the Queen become jealous of Charles and the admiral’s relationship, so she had to get rid of Coligny. Therefore, she conspired against the admiral. How exactly did she do it? With the help of the Guise family. She persuaded Charles that the admiral was planning to have Protestantism become the dominate religion in France, overthrowing the Catholics. The King, fearing that the Spanish forces now had a motive to invade France and that the Huguenots would take control of the Catholic church, agreed to the assassination of the admiral.6 The young king Charles was a weak leader, easily manipulated and influenced to do what others wanted of him; Charles was the prey of many, including his own mother.

On August 18, 1572, the day of the wedding between Margaret and Henry, the ceremony was performed in the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris.7 The wedding brought days of festivities; among those attending were noble Huguenots who were in Paris to celebrate with their leader, Henry of Navarre. Queen Catherine, Charles, and the Guise family, however, were planning a different type of celebration. They were planning to get rid of the admiral. The plan was set in motion, and four days after the wedding, on August 22, a man hired by the Guise family was to do the bloody work for them; Maurevert was recruited to assassinate Admiral Coligny.8 Maurevert shot from a window, hitting the admiral with two bullets. One bullet hit a finger on his right hand and the other hit his left arm, leaving him very much alive. The failed murder of Coligny caused great fear in the Guise family, as well as to Catherine and to Charles, who feared that the admiral was aware that they had been the ones behind the shooting. In their moment of fear, Charles commanded a mass slaughter of Coligny and his followers, so that none of them could retaliate against him and his family. Because they knew many Huguenots were in Paris celebrating the wedding festivities, it would be a large number of Huguenots that would be slaughtered. No Huguenot would expect it; therefore, none would be able to fight back. The king gave the order: “Qu’on les rue tous,” meaning that all must be slain.9

Nevertheless, the admiral was unaware of who was behind his attempted assassination. While the admiral was taken to his home to be aided and to recover, he wept: “I think myself blessed to have received these wounds in God’s cause …. I forgive freely and with all my heart, both him that struck me and those who incited him to do it; for I am sure it is not in their power to do me any evil, not even if they kill me.”10

On August 24, two days after the attempted assassination of the admiral, an order was given by King Charles to finally perform the deed and execute Coligny. Finally succeeding, Coligny was stabbed in the chest, his head decapitated and his body severely mutilated, and then his corpse was thrown out the window of his home. The remains of his body were burned and thrown into the river and removed again. Claude Haton, a Catholic priest, described the happening “as unworthy to be food for fish.”11 His head was also said to have been used by Parisian children as a ball for entertainment. What came after Coligny’s killing was massive bloodshed. The Huguenots that had gathered around the Louvre Palace were attacked by hired thugs and criminals to slaughter as many Huguenots as they could find. Soon Parisian Catholics begin to join in on the act. Among the victims of the Saint Bartholomew’s massacre were men, women, and children whose bodies were mutilated and left to rot; and some were thrown into the Seine river. Arms, legs, and heads of the innocent all littered the streets of Paris. One known victim was Peter Ramus, an important French philosopher who reorganized Aristotle’s thinking.12 The event in Paris inspired Catholic citizens to join in on the act, and the murder spread to nearby cities: Lyon, Rouen, Bordeaux, and Toulouse all experienced the violence of the Catholic mob.13

Across Europe, the Protestant community was utterly shocked at the horror of the massacres, while the Catholic community celebrated the murder of the Huguenots. Pope Gregory XIII ordered the bells in Rome to ring in celebration of the St. Bartholomew’s massacre, even issuing a medal celebrating the slaughter of the Huguenots.14 The horror of lives lost at Paris and in its neighboring regions were never confirmed, but it is estimated that about 10,000 innocent individuals lost their lives to the violence of the Catholic mob. Although many historians still question why the massacres transpired and who the leading mastermind behind the assassinations were, one thing that all can agree on is that the Saint Bartholomew’s Massacre was one of the worst atrocities brought about by the hatred and revenge of individuals because of religion tensions. If either the Queen, the Peace of Saint-Germain, or Admiral Coligny’s chapter in the King’s life triggered the massacre, it will continue to be a question that will have differing answers. After the assassination of the Huguenots in France, the fourth war on religion soon begin and the division between the Catholics and Protestants continued. France during the sixteenth century was painted in red, and the event known as “The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre” will remain a bold punctuation mark in the heart of that century.

- Edward Wheland, “What was the Impact of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572) on France?,” DailyHistory.org, (May 2017). https://dailyhistory.org/What_was_the_impact_of_the_St_Bartholomew%27s_Day_Massacre_(1572)_on_France%3F. ↵

- Henry White, The Massacre of St. Bartholomew’s (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, Franklin Square, 1868), 317. ↵

- World History Encyclopedia, 2011, s.v. “French wars of Religion, 1562-1598.” ↵

- Frank Ardolino, “In Paris? Mass, and Well Remembered,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 21, no. 3 (1990): 401. ↵

- New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2003, s.v. “St. Bartholomew’s Day, Massacre of,” by W.J. Stankiewiez. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2003, s.v. “St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre,” by James F. Hitchcock. ↵

- Henry White, The Massacre of St. Bartholomew’s (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, Franklin Square, 1868), 372. ↵

- James R. Smither, “The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre and Images of Kingship France: 1572-1574, “The Sixteenth Century Journal 22, no. 1 (1991): 29. ↵

- New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2003, s.v. “St. Bartholomew’s Day, Massacre of,” by W.J. Stankiewiez. ↵

- Henry White, The Massacre of St. Bartholomew’s (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, Franklin Square, 1868, 380-381. ↵

- Henry White, The Massacre of St. Bartholomew’s (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, Franklin Square, 1868, 411. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2003, s.v. “St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre,” by James F. Hitchcock. ↵

- Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World, 2004, s.v. “St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre,” by Barbara Diefendorf. ↵

- Edward Wheland, “What was the Impact of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572) on France?,” DailyHistory.org, (May 2017). https://dailyhistory.org/What_was_the_impact_of_the_St_Bartholomew%27s_Day_Massacre_(1572)_on_France%3F. ↵

121 comments

Marie Peterson

This was an interesting story to learn about. Before this article, I had heard of this event but knew nothing about it. I find it interesting how much pain and killing is and has been done in the name of religion. This is an example of that caused by the war between Catholicism and Protestants. Even after these events, there was still so much more fighting over this specific argument. Great job!

Gabriella Parra

It’s interesting how this massacre was so organized. When I think of massacres, I think of spur of the moment actions. Like-minded people seeing a closing opportunity and taking it. While this massacre was a last-minute decision to some extent, it really seems as though the Huguenots were lured to Paris to be slain. Since Charles was young and largely influenced by his mother, I’d like to read more about what he personally thought about this situation, apart from all his advisors.

Brandon Vasquez

To me this article was extremely interesting as I did not know what this event was in history. To me it is kind of crazy how the queen ultimately got what she wanted by lying to her husband. The problem of religion was huge in Europe and with the marriage of a protestant and a catholic one would believe that the problem would be solved however it was not.

Alanna Hernandez

The religious wars expose the Protestants and Catholic’s crazy stories that are hard to believe as part of their history. This article is a perfect example of the tensions and slaughter that was brought from a religious war, going even further than most discuss, a going into deep detail of the horrendous massacre and the politicalzation of it as a whole.

Jacob Salinas

This was a very well written article that depicted the St. Barthomlomew’s Day massacre. This was an event that I had not heard of, so it was very interesting to read up about the topic. This article shows how the relationship between the Catholics and the Protestants was not on good terms. Even though Prince Henry and Margaret of Valois got married, one catholic and one protestant, there was still no peace between the Catholics and the Protestants.

Lauren Deleon

I find it so fascinating that historians are still unsure of what led to the massacre and who was really behind it. It is difficult to tell a story with only speculation and theories to go on and you did a fantastic job! I am inclined to believe that Queen Catherine was behind the violence just because of other things about her over the years. History tends to paint her as a cruel and conniving women. I guess we will never really know the reason behind the massacre, but I think most people would agree whatever it was, it could not have justified that level of violence.

Luke Rodriguez

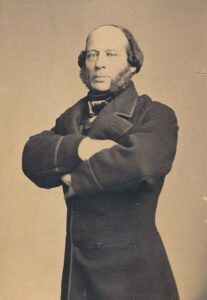

I found this article to be very informative. One thing I enjoyed about it was that it already gave me a lot of fascinating facts at the beginning of the article, which was a very cool feature. A good thing about the article was the use of images with descriptions throughout the text. I could visualize what was going on in the scene because of it.

Eugenio Gonzalez

The article is well-written and does a great job of describing the tragedy of St. Bartholomew’s day. Before reading this article, I had no idea that this incident took over and its magnitude. One would believe that tensions between Protestants and Catholics would ease with the marriage of Prince Herry of Navarrete and Margaret of Valois, but unfortunately, that was not the case.

Melyna Martinez

I believe this article shows the power of religious wars, especially in these times for the Catholics and the protestants. The massacre they created for the power of religion has insane outcomes, even when a marriage between a catholic and a protestant caused more danger for religious freedom. I believe the article really captivates the power religion has and how it can cause wars that put millions of people’s lives at risk.

Kristen Leary

It is so interesting to me that all this bloodshed occurred on what seemed to be an attempt at unifying and breaking religious tensions through a strategic marriage. It is unfortunate how political these things were, and how decisions were made out of fear of invasion from other nations with differing religious beliefs. Great job on a descriptive and engaging article.