Although much has been written about the effects of colonization on the Native American community, it is only in recent years that historians have established that the colonization of the Native American community did not end once reservations were established in 1851; it persisted throughout the classrooms through an education system based on Indian boarding school founder Captain Richard Henry Pratt’s idea, “Kill the Indian and Save the Man” (Dawley 282). Native American children were forced to assimilate into an Anglicized way of life; as stated in the book Carlisle Indian Industrial School, “There seemed to be no end to the cruelties perpetrated by whites. And after all this, the schools. After all this, the white man had concluded that the only way to save Indians was to destroy them, and that the last great Indian war should be waged against children. They were coming for the children” (Fear-Segal and Rose 7). The mass cultural genocide committed against the Native American community within the walls of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which took place from 1879 to 1918, has left an irreversible trauma on the Native American community, according to the authors Fear-Segal and Rose, Capt. Richard Henry Pratt specifically designed the boarding school with the sole purpose of “[r]emoving Native children as far as possible from their families and communities, to strip them of all aspects of their traditional cultures, and to instruct them in the language, religion, behavior, and skills of mainstream white society” (Fear-Segal and Rose 1). As a result of the severe trauma inflicted on the Native community, not much is known about the Native American boarding schools since there is a lack of storytelling within the Native American communities themselves. A lack of personal accounts in the history books can be attributed to the lack of representation and justice for many of the victims of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. As a result, the students enrolled in these boarding schools endured punishments that would alter the course of their lives, with stories of the victims only beginning to resurface in recent years.

History

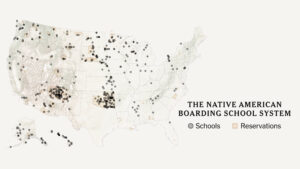

Pratt’s primary intention for creating the Carlisle boarding school and its education system was to solve the “Indian problem.” Establishing a boarding school catering to Native American children would allow for total control of the Native population. In the article “Indian Boarding School Tattooing Experiences” by Martina Michelle Dawley, she notes that the belief for solving the “Indian problem” was through the “notion of assimilation through total immersion” (Dawley 282). If Native American children were immersed in the Anglocentric ways of doing things at an age where they could more easily assimilate compared to their parents, the assimilation of these children could mean that, over time, the Native American community and culture could come to an end. To succeed with this goal of forced assimilation, “Carlisle provided the blueprint for the federal Indian school system that would be organized across the United States, with twenty-four analogous military-style, off-reservation schools and similar boarding institutions on every reservation” (Fear-Segal and Rose 1). In the book Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Pratt states that his “objective was to prepare Native youth for assimilation and American citizenship” (Fear-Segal and Rose 1). The usage of the term American “citizenship” by Pratt is an ironic one considering Native Americans are the Native citizens of the land Pratt is referring to. This kind of rhetoric showcases the mentality rampant throughout the 19th century, which helped fuel Pratt’s creation of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School as another means to attack and convert the Native American community, “… Native nations now sequestered on reservations, Pratt and white Christian reformers, who called themselves “Friends of the Indian,” presented the policy of education and assimilation as a more enlightened and humane way to solve the nation’s intractable “Indian Problem.” Yet the purpose of the “education” campaign matched previous policies: dispossessing Native peoples of their lands and extinguishing their existence as distinct groups that threatened the nation-building project of the United States” (Fear-Segal and Rose 1). One of the obstacles Pratt had to overcome to gain support for his school was convincing the Anglo public that the boarding school would be a good financial investment and solve the “Indian Problem” that many Anglo-Americans feared since taxpayer money was the primary source of funding (Fear-Segal and Rose 7). Pratt insisted that the supposed wild and savage nature of the Natives could be changed in just one generation through the boarding school system. Pratt’s continuous claims quickly gained support and even favorable responses from the Anglo community. To further gain support, in 1883, Pratt spoke at a Baptist convention and explained the philosophy of assimilation by using the image of baptism, “In Indian civilization, I am a Baptist because I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization, and when we get them under holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked” (Fear-Segal and Rose 6). This religious propaganda was later used in the classrooms at Carlisle. Using Christianity as part of the education that the Native American students at Carlisle received created a long-lasting identity conflict in the lives of Native American students.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School

“During its thirty-nine-year History, over 10,500 students from almost every Native nation in the United States (as well as Puerto Rico) were enrolled at Carlisle…The first students forcefully enrolled in the Carlisle Indian Industrial School came from the tribes of Lakotas, Kiowas, and Cheyennes, who were deemed by the American military as the most “troublesome” (Fear-Segal and Rose 5). On some occasions, Native American children would be enrolled at Carlisle by the will of their parents. These Native American parents were under the false impression that if their kids attended a school taught by an Anglo staff in an Anglo community, with teachings based on the standards set by an Anglo society, their kids would have a higher chance of surviving in “white” America, which was not the case. According to Carlisle Indian Industrial School, “At Carlisle, students were rarely placed with a roommate from the same nation, so they would be forced to speak English. Carlisle students were enrolled initially for a period of three to five years. Most did not return home during that time, and many spent far longer at Carlisle. Instead of returning home for the summers, they were sent “Out” into local communities to work for white families, typically as farmhands or maids” (Fear-Segal and Rose 5-6). The “education” provided at Carlisle was explicitly designed to force Native students to disconnect from their Native ancestral roots and to place them in subservient roles in society. As stated by a recount of Sun Elk, who attended the Carlisle Indian School (1883–90),

“[t]hey told us that Indian ways were bad. They said we must get civilized. I remember that word, too. It means ‘be like the white man.’ I am willing to be like the white man, but I did not believe the Indian ways were wrong. But they kept teaching us for seven years. And the books told how bad the Indians had been to the white men—burning their towns and killing their women and children. But I had seen white men do that to Indians. We all wore white man’s clothes and ate white man’s food and went to white man’s churches and spoke white man’s talk. And so after a while we also began to say Indians were bad. We laughed at our own people and their blankets and cooking pots and sacred societies and dances”. (Fear-Segal and Rose 12).

Psychological abuse such as the one described by Sun Elk was not the only form of conversion used against the Native students. For example, physical punishments at Carlisle included “whip-pings, wearing a ball and chain, getting locked in a dark closet or isolation, hard labor, imprisonment, and shaving of head,” with accounts of former students recalling “runaways being forced to eat their own vomit after subjected to a meal of spoiled food” (Dawley 284). Another obstacle the students at Carlisle faced was the disconnect between themselves and their teachers. According to various interviews conducted by Terry Huffman on twenty-one American Indian educators in the article American Indian Educators in Reservation Schools, “American Indian teachers serve as natural role models, and thus they can build the personal connections necessary for effective instruction” (Huffman ch.4). Because of the natural connection Native American students have towards their community, being in a classroom where the teacher did not look like them or practice their values made it especially hard for these students to adapt. For example, the curriculum enforced by non-native teachers at boarding schools stripped Native children of their ethnic identity, which further enforced the disconnection between the students and the classroom since it served as a place of fear, not learning.

In order to continue receiving support from the government and the Anglo public, Pratt had to expand his propaganda by working with photographer John Nicholas Choate “[t]o create visual “proof” of his experiment’s success. The image of the “savage” Indian so prevalently promoted in previous years was replaced with the notion of the less threatening, ‘docile, pacified Indians’ on their way to civilization” (Fear-Segal and Rose 8). Another factor for the federal government’s support of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the economic “benefits” it would bring, “Henry Teller, a secretary of the interior, argued that it would cost $22 million to wage war against Indians over a ten-year period, but it would cost less than a quarter of that amount to educate thirty thousand children for a year” (Fear-Segal and Rose 7). Even though the Carlisle Indian Industrial School received monetary support from the government, it was still heavily underfunded. One of the most concerning consequences of the establishment’s underfunding was the multiple health hazards that erupted from the boarding schools, which devastated the entire Native community. According to the article “Unless They Are Kept Alive” by David DeJong, a survey taken in 1913 by thirteen medical officers and assistant surgeon general J. W. Kerr found that the health conditions in Indian communities were at a hazardous level, with Indian boarding schools being the leading cause of such high levels (DeJong 271). According to the findings, “tuberculosis increased to six times the non-Indian rate, and Indian boarding schools continued to “facilitate, rather than prevent,” disease” (DeJong 274). Because of the lack of hygiene, improper diets, lack of medical attention, and overcrowding in the boarding schools, the transmission of diseases was the main cause of death for Native children within these boarding schools (DeJong 275). With many of the infected students returning home to the reservations, it allowed for the transmission of diseases that had never before been in contact with the Native American community, “[t]he tuberculosis rates spoke for themselves: the Indian rate per 100,000 was 46.9; among African Americans, it was 33.9; among Anglos, it was 12.1.” (DeJong 271).

Resistance

While these numbers show the health decline in the Native community, they fail to show the resistance of students at boarding schools. One of the major ways students fought forced assimilation was through tattooing. It was a prevalent practice among female students from the 1960s through the 1970s. Dawley’s article Indian Boarding School Tattooing Experiences provides insight into the unknown practice of tattooing, which is absent from any “literature related to the American Indian boarding school experience and any type of Indigenous-related ethnography” (Dawley 281). The practice of tattooing would entail a simple yet powerful message: resistance. Girls would sneak into the restrooms late at night and, with a needle, write their initials. The punishment for being caught was severe, but this did not stop the practice of tattooing within the female student body. More examples of resistance progressed into acts of “running away, sneaking off campus, speaking Native languages on the sly and inventing derogatory names for authorities, practicing Native customs and religion, making home brews, destroying school property, and playing pranks” (Dawley 283). Many students also took passive resistance, which allowed them to challenge the system by becoming over-achievers. No matter the method for demonstrating resistance against the Carlisle Indian Industrial School system, the message was the same. It demonstrated the will of the Native students’ urge to fight back against the assimilation forced on them.

Other examples of resistance emerged in boarding schools in New Mexico and beyond. The book Education at the Edge of Empire: Negotiating Pueblo Identity in New Mexico’s Indian Boarding Schools by John R. Gram describes how the Pueblo Native Americans were able to,

“Gain significant influence over how the boarding schools would function and ultimately over what they would mean for their children, themselves, and their future” (Gram 174). The circumstances that allowed for this power shift included the underfunding and low supply inventory affecting the Albuquerque and Santa Fe Indian Schools. The need for students was critical for the schools to keep their doors open. This dependency on the Pueblo community led the “superintendents to compromise and negotiate with the Pueblos” (Gram 174).

Even though the Pueblo community made choices regarding the boarding schools, the children were still open to facing the same punishments as the ones from other boarding schools. In 1904 Capt. Richard Henry Pratt was dismissed, and with it left the “the goal of rapid assimilation, fiercely championed at Carlisle and closely linked to the perceived need to subjugate Native peoples and possess their lands, instead, it was replaced by a national Indian schooling program with a slower pace, more lowly ambitions, and requiring a much smaller budget. Reservation schools, teaching a simple and basic curriculum, were now deemed to be the best way to accommodate Indian ‘incapacities” (Fear-Segal and Rose 10). During 1913 and 1914, a Senate investigation gained the public’s attention for uncovering abuse at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. This investigation and the philosophy of “assimilation through total immersion” (Dawley 282), which had initially drawn support for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was now also being questioned and eventually led to the closure of Carlisle in 1918. “The surviving buildings from the Indian school were put to new and different purposes with most of the schools turned into army training camps” (Fear-Segal and Rose 11). In addition, the cemetery at Carlisle, where many of the Native children were buried, was deemed an obstruction to the new facilities in place, leading to its movement outside the grounds. Carlisle Indian Industrial School states that even though the closure of Carlisle led to the History of the Indian Industrial School being forgotten, “On Indian reservations across the United States, however, among Native descendants, families, and communities, the traumatic legacies of Carlisle and the boarding school experiment it spearheaded continued to have an enduring impact whether spoken of or silenced” (Fear-Segal and Rose 11).

Identity

One such legacy emerges through the concept of “cultural genocide,” which describes the treatment of Native Americans on American soil. It was chosen because it was a more “humane” term (Fear-Segal and Rose 7). The cruel and unfair punishments the Native community have faced over the decades come from a society representing those oppressive views and values. The Native children at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School were victims of physical, sexual, physiological, and spiritual abuse. Taking these children away from their homes at such an early age and in such a traumatic way was bound to leave a mark on each individual for the rest of their lives. In the classrooms, students were taught that being Native was bad and that one must act “white” to not be like the “savage” Indian. These teachings were the beginning of the end for the identity of many Native American children. They were the main contributors to the identity crisis that would soon engulf the students at boarding schools like Carlisle. For the rest of the Native community, “Pratt’s experiment at Carlisle initiated processes of diaspora, dislocation, and rupture deeper and more profound than he envisaged” (Fear-Segal and Rose 7). The aftermath of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School had many immediate impacts, but most effects were only seen after years of trauma. Many of the students at Carlisle eventually returned home only to find themselves “[c]aught between worlds, cultures, and languages. Cut off from nurturing tradition, family, and community, they experienced a rupture in their affiliations, affections, and identities. For many, this began a legacy of trauma and disenfranchisement that would be passed down the generations” (Fear-Segal and Rose 6). Unlike the hopes of Capt. Richard Henry Pratt, most students who attended Carlisle did not assimilate into “white” society. In fact, “Only 758 of over 10,500 students who were enrolled at Carlisle ever graduated” (Fear-Segal and Rose 2). The failed assimilation process through boarding schools not only stripped Native children of their identity but further stripped them of their land. For most people, territory serves not only as a means for income and protection; the land itself is tied to one’s identity. It has become apparent that over the years, the US government has taken advantage of the Native American territory and, therefore, restricted their sovereignty. According to the book American Indian Sovereignty: The Struggle for Religious, Cultural and Tribal Independence by J. Mark Hazlett II, “[f]or American Indians, the debate over tribal sovereignty began when the first explorers and colonizing powers landed on American shores. Each wave of European newcomers made subsequent claims of sovereignty over the Indians based upon their own decrees, doctrines, or desires. This meant that Indians lost their rights, freedoms, and independence except for those granted graciously to them by the new authority. This initial stage has set Indian sovereignty on a long path of debate and controversy” (Hazlett 17). The impact of the limitation on the sovereignty of the Native American people has led to multiple identity issues within the community, “[t]erritory, an ancestral homeland, is closely tied to both one’s identity as a tribal member and to the group within the larger sphere of society. By limiting the powers and rights of a tribe over their homeland, then one limits the powers and rights of the individual members also” (Hazlett 16). The identity issues that the students developed at Carlisle and other boarding schools have haunted them and the generations after them. They have ripped apart individuals and torn a deep hole in the Native American community. It is the telling of stories and experiences in places like Carlisle that have allowed for the healing of these communities to start taking place.

Conclusion

History is a powerful tool that can be used to shape future generations. Therefore, it is essential to consider how historical narratives are shaped and told. Just as students at Carlisle were fed misinformed accounts of history, we must also question the renditions we learn. This led them to resent their culture and heritage because their history was being told to them through an Anglocentric lens, “[t]he Carlisle Indian School contains and conveys a powerful and contentious history. Its past still haunts the present, in large part because its past has not been fully told” (Fear-Segal and Rose 19). While the records of history might indicate something, one must analyze where this information comes from, “we need to interrogate history” (Fear-Segal and Rose 19). In the case of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, most of the accounts are told by Capt. Richard Henry Pratt and the staff who worked at the school. Very little is known about the in-depth personal accounts of the student’s experience at Carlisle, “[t]t is useful here to acknowledge how the differing silences that surround Carlisle have had an enduring impact on how the history of boarding schools has been communicated within mainstream society and the ways in which they curtailed the potential for Native communities to research, discuss, and even know their own stories” (Fear-Segal and Rose 20). Although the name “Carlisle” might not be of much significance to most people nowadays, it still resonates with the Native American community as a reminder of the pain and torment endured by their children and community. Through all the hardships the Native American community has endured over the centuries, it can be hard to focus on the positive aspects that History has brought the community. Nevertheless, progress is achievable through responsibility and accountability, allowing for the community’s healing. The resilience that the Native American community possesses demonstrates the fundamental values that Native Americans continue to hold within themselves, their community, and their land.

Works Cited

Dawley, Martina Michelle . “Indian Boarding School Tattooing Experiences: Resistance, Power, and Control through Personal Narratives.” American Indian Quarterly 44, no. 3 (2020): 279. https://doi.org/10.5250/amerindiquar.44.3.0279.

DeJong, David H. “‘Unless They Are Kept Alive’: Federal Indian Schools and Student Health, 1878-1918.” The American Indian Quarterly 31, no. 2 (2007): 256–82. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2007.0022.

Fear-Segal, Jacqueline, and Susan D. Rose. Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, and Reclamations. Lincoln; London: University of Nebraska Press, Cop, 2016.

Gram, John R. Education at the Edge of Empire. University of Washington Press, 2015.

Hazlett, Mark. American Indian Sovereignty. McFarland, 2020.

Huffman, Terry. American Indian Educators in Reservation Schools. University of Nevada Press, 2013.

8 comments

Martin Martinez

I have always considered the Native American problem a unique one because it involves the displacement of those who were here first. It is a sad history that is not nearly as covered as much as it should be. However, what these people have been through is no less impressive. It is a story that needs to be told.

Maria Fernanda Guerrero

Its saddening that ethnic racism was allowed. I often wonder how can humans do such awful things to one another, is that is who we are, made to make mistakes after mistakes until we learn. This is how ethnic racism became illegal, no? After centuries of targeting and oppressing certain ethnic groups we learned it was inhumane and immoral, correct? So when until we all realize that racism in general is wrong. After more decades?

Fernando Milian

It is unfortunate that these types of actions have taken place in history because they caused irreparable damage to indigenous communities, affecting not only their autonomy and culture, but also their identity and generational legacy. These events reflect a sad reality about oppression and the attempt at forced assimilation, which continues to have repercussions to this day in the relationships and in the fight for justice and the recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples. Thanks for this great article.

Lauren Sahadi

This article explored the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and the impact on Native American communities. It’s awful to read about what these people went through and the trauma that came from it. Although it was sad to read, I think it’s important to know the good and bad of history. I liked how u added some good within the article that switches the mood. Very powerful article.

Gaitan Martinez

It’s very upsetting to learn about an ethnic group being oppressed, assimilated, or targeted. One of the main characteristics that all humans share is diversity, we are all so different, yet the same. I would argue that we need diversity because it helps us develop as a society, if everyone is the same, then it would be boring and society could slowly develop. I remember going to the missions in middle school and it was an interesting, yet a disturbing experience because no one could truly understand the morbid reality because we were not there.

Jonathan Flores

Congratulations on a very well done article and picking a topic that is so unique and thought provoking. I always find it interesting that facets of American history as you have written about were not present in my public school education. In this way, it highlights the disparities and ignorance of knowledge many people have regarding Native Americans. As a result, I feel as though I learned a lot about a topic I knew some about, but this really helped show just how disadvantaged the native peoples of this country were. I appreciate your commitment to such an important topic and well done.

Esmeralda Gomez

As someone with roots in a Native American tribe, reading about the history of assimilation through total immersion at Native American boarding schools was actually eye-opening. This article really captured the complexities and challenges faced by indigenous communities during that time and even transcends its time by some of the issues Native Americans faced then being faced by countless immigrants now. It’s a reminder of the resilience of these cultures and the importance of acknowledging past injustices for a better future.

Linda Aguilar

I enjoyed reading the article “Assimilation through total immersion.”

The colonization through the education system during this time where Indian children were forced to assimilate was difficult for children. This article is well written and gives a perspective of the difficult times in our history. It is important to recognize a time when genocide occurred to the Native Americans. Fantastic job!