(Trigger Warning: Plantation Sexual Assault)

On June 17, 2020, the Quaker Oats Company announced its decision to rename its Aunt Jemima pancake brand after 131 years. Since then, the public has received this news with mixed feelings and opinions. How did Quaker Oats acquire Aunt Jemima? And why is she being removed? To answer these questions, let’s first take a look at Aunt Jemima’s beginnings, then where she’s been over the years, and what she means now.1

In 1888, Chris Rutt and Charles Underwood acquired a bankrupt flour mill in St. Joseph, Missouri. Shortly after their acquisition, in the summer of 1889, they created a completely new product—a pre-made, self-rising flour pancake mix—made of flour, corn flour, lime phosphate, and salt. Luckily for Rutt and Underwood, they made their product at the perfect time. New methods of paper-packaging food products made it possible for companies to create a product, package it, and then transport it to other parts of the United States. Such an innovation sparked the importance of food branding, since products now had the potential to reach a national audience.2

Because packaging allowed consumers to recognize their favorite products on the store shelves, Rutt and Underwood searched for a strong brand image to capitalize on their unique concept. The brand needed to lean into the idea of a comfortable home, with hot pancakes ready on the breakfast table. It needed to be “something familiar, accepted, [and] inviting.”3 In Autumn 1889, as he was walking through the city of St. Joseph, Rutt stumbled upon a minstrel show. As the performers—men in painted blackface—entertained Rutt with a plantation skit and a song, the idea came to his mind for his pancake mix company: the mammy, Aunt Jemima.4

I went to church the other day,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

To hear them white folks sing and pray,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

They prayed so long I couldn’t stay,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!

I knew the Lord would come that way,

Old Aunt Jemima, oh! oh! oh!5

Minstrel shows were culturally significant at the time of Rutt’s discovery, as they portrayed a romantic, pastoral view of the Antebellum “Old South” while, simultaneously, cemented negative stereotypes of African-Americans through blackface. In response to the Reconstruction of a “New South” following the American Civil War, many southerners created minstrel shows, poems, plays, books, and advertisements to capture the nostalgia of the Antebellum South, “a nearly perfect land, ‘studded with magnolias.'”6 However, most of these glossy depictions of White leisure and abundance failed to accurately describe the trauma and realities of enslaved Black people. Why was this the case? Why did White creators of minstrel shows and the audiences who watched them want to hold on to this type of nostalgia? After the defeat of the Civil War, southerners clung to the idea of a “simpler” time when the social structure benefitted them. Black people, now liberated from slavery and guaranteed new rights under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, were now technically legally equal to White people in the South. That changed reality was not easy for White southerners to accept. Additionally, reconciliation between the North and South was necessary to preserve the symbiotic relationship between Northern and Southern economies. The North needed Southern agricultural goods and the South need Northern manufacturing products. Therefore, White people controlled the false narrative of an “Old Southern” harmonious racial order to piece together the divided country and to justify their racism and the eventual Jim Crow South.7 Among the trappings of the “Old South,” Rutt produced a perfect symbol for his brand of pancake mix: the “mammy.”

An enslaved Black woman who lived inside the plantation home, the mammy was (and still is) a strong figure in American literature, film, and advertising. Depicted as usually fat, motherly, or bossy, her primary responsibilities were cooking, housekeeping, and taking care of White children. Believers of a romantic “Old South” simply saw the enslaved caretaker of children (usually nicknamed with the endearing name “mammy” or “aunt”) as a beloved figure, an example of the peaceful relationships between White and Black people. After all, the mammy nursed and raised White children, and she had the highest enslaved position on the plantation. In many ways, media portrayed her as second in authority only to the master and mistress of the plantation as she “kept other slaves in line.”8 Perhaps the most famous portrayal of the devoted mammy was Hattie McDonald’s in the 1939 romantic antebellum period piece, Gone with the Wind. However, according to historian Deborah Gray White, this image of the mammy was “always more white self-delusion than slave reality.”9 For example, many of us have viewed the mammy as a naturally talented cook. True, the culinary genius of Southern African-American women is underrated. However, the dynamic in the 1800s was less “chef to guest” and more “prisoner to master.” In fact, Southern belles would make “plantation-style” cookbooks to record their family history and then steal the intellectual property and recipes of Black women to include inside. This example shows that White enslavers often simultaneously took advantage of and loathed their Black servants.10

While appearing fairly innocuous on the surface, the mammy is a complex figure with a deceptive underside, and her strong presence in American culture says much about the social order of the American South. Postbellum White male authors have used mammy as a contrasting image to the “Jezebel” stereotype. Depicted as a dangerous Black woman who lured White men into interracial sex, the Jezebel character was used to excuse and explain away slave rape and sexual assault. On the other hand, the mammy, who was often older and sexless, posed no threat to the sexual order of the “Old South” and supported White families with her loyal service. In tandem, these two stereotypes of the Jezebel and the mammy sent a message that Black women were dangerous when they were not under proper White control.11

Additionally, mammy’s perceived loyalty and closeness to White enslavers has been used to justify the institution of slavery itself, because she has been depicted as content and happy with her circumstances.12 She has been depicted as “the perfect slave” and represents a mythical, harmonious relationship between Black and White people during the “Old South.” Aunt Jemima’s accepted image suggests a popular, romantic longing for a bygone era, despite how false or problematic that time may have been. According to Riché Richardson, a professor of African-American literature, this stereotype “is premised on notions of Black otherness and inferiority, that harkens back to a time when Black people were thought of and idealized mainly in relation to servant positions.”13 This “otherness” and “inferiority” can be seen clearly in the mammy’s cartoonish depictions. Additionally, the beloved attitudes towards the mammy, in both the North and South, allowed White folks to reconcile after the Civil War. The mammy painted as a devoted slave to her masters, redeemed Southerners and their plantation system. According to Jo-Ann Morgan, “Seeing the former slave woman visually transformed into a contented servant absolved everyone of past transgressions and future responsibility toward the freed people.”14 Ultimately, the fiction of a motherly, nurturing, servant is why Rutt chose the mammy, Aunt Jemima, for his pancake brand. White people felt comforted both by her domestic role and her reminder of racialized social order.15

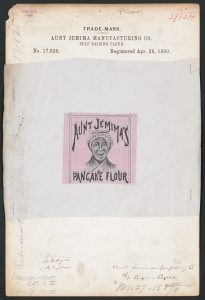

Aunt Jemima first appeared on a sack of flour in 1889. In 1890, Rutt and Underwood sold the company and its pancake recipe to R. T. Davis. After acquiring the new R. T. Davis Milling Company, Davis changed the recipe to improve its texture, and he also added powdered milk. This made it so that “housewives needed only Aunt Jemima and water to make [delicious] pancakes.”16 But most importantly, Davis contributed to the lore of Aunt Jemima. He sent out requests to find Aunt Jemima’s personification, a “real” slave woman. According to historian M. M. Manring, “A real living Black woman, instead of a White man in blackface and drag, would reinforce the product’s authenticity and origin as the creation of a real ex-slave.”17 Davis found his Aunt Jemima in Nancy Green, a fifty-nine-year-old servant born into slavery on a Kentucky plantation. She made her debut at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago by serving pancakes, singing songs, and telling real (and apocryphal) slave stories. The Exposition proved to be successful as merchant attendees placed more than fifty thousand orders for the pancake mix. Most importantly, the public also bought into Aunt Jemima’s persona.18

Davis’s brand manager, Purd Wright, went a step further and wrote the earliest version of Aunt Jemima’s history, The Life of Aunt Jemima, the Most Famous Colored Woman in the World. The pamphlet took stories from Green’s actual life and blended them with fiction. According to Wright, Aunt Jemima cooked for Louisiana’s Colonel Higbee, and during the Civil War, she offered her famous pancakes to northerner troops to help her enslaver escape. The story behind Aunt Jemima continued to grow as the company was renamed Aunt Jemima Mills in 1903, and then later bought by the Quaker Oats Company in 1925. Over time, she gained a fictional family, and through a coupon promotion, consumers too could have Aunt Jemima join their families by earning the Aunt Jemima family ragdolls.19

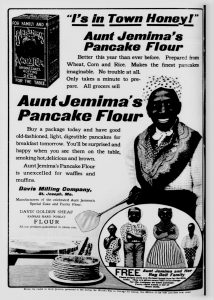

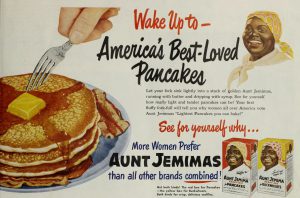

Aunt Jemima was successful throughout the twentieth century because of three main socio-cultural contexts: the “Servant Crisis,” the increase of labor-saving machines, and the appeal of the Old South imagery in advertising. The “Servant Crisis” was a shortage of domestic servants during the early decades of the 1900s. More Black women moved into servant positions because of this, especially during the Great Northward Migration when Black people were fleeing from the South. Advertisers used this “crisis” to their advantage by visually attaching a household servant to commercial products. These products suggested servants were unnecessary while simultaneously giving these products a luxurious identity. Aunt Jemima’s brand captured the essence of one’s very own household servant.20

Additionally, women were also drawn to the idea of a personal household servant because of the creation and commercialization of labor-saving appliances, like electric stove-top ovens and vacuum cleaners. Ironically, these appliances produced more work for housewives in the twentieth century by applying pressure on women to clean more thoroughly and cook big, complicated meals for their families. Knowing this, many advertisers preyed upon women’s insecurities to accomplish more in the home. Advertiser James Webb Young perfected this method of advertising with “whisper campaigns,” where an advertisement would depict usually a woman talking about another woman’s messy home, bad food, or hygiene behind her back. Young’s 1919 “whispers” increased sales for Odorono lady deodorant by 112% in just a year. Knowing how to manipulate consumers and convince them of their need for their own Aunt Jemima, Young went on to become the campaigner for Aunt Jemima throughout the 1920s.21

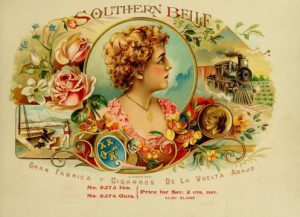

Finally, the narrative of the romantic “Old South” also proved to be an effective advertising method in the early 1900s. The preindustrial southern agriculture depicted a lush “garden of eatin.”22 Products like Baker’s Coconut and Maxwell House Coffee capitalized on the perceived abundance and luxury of living in the American South. Young knew this and Aunt Jemima’s brand benefitted from this trend, as she was marketed as a nurturer of White people.23 In the mid-to-late-twentieth century, Aunt Jemima’s persona remained steady. From 1955 to 1970, Disneyland operated “Aunt Jemima’s Pancake House.” An Aunt Jemima in a plaid dress, apron, and kerchief would serve food to guests, sing songs, and pose for pictures with patrons.24

The earliest criticism of the Aunt Jemima brand was in 1918 by Black journalist Cyril V. Briggs. The editor of the New York Crusader called upon his race to boycott the brand because the White-created depiction of Aunt Jemima represented “ugliness, depravity, and subservience” among Black people, similar to the blackface depicted in minstrel shows.25 Briggs was not the only Black person who disliked the Black depiction of Aunt Jemima. According to Paul K. Edward’s 1932-study about African-American consumers, he found that Black consumers favored advertisements that featured Black people because they were inclusive. However, when shown advertisements of Aunt Jemima, Black consumers disapproved of the brand’s portrayal of African-American people. Black men and women from different levels of class and education gave feedback from “plays upon idea of Negro in slavery too much” to “I positively hate this illustration.”26

Following the 1932-study, Aunt Jemima’s existence continued to be debated and negotiated. During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s, the NAACP called upon consumers to boycott the brand. The Springfield, Illinois NAACP Chapter brought about some success in 1956 by pressuring the Florence Gas Range to cancel live Aunt Jemima performances. Unfortunately, the Springfield Chapter was ridiculed by local papers because the boycott seemed frivolous and unimportant for such a brand. The NAACP also called upon the Super Market Institute to end other promotional performances in markets. In 1968, Quaker Oats responded to the criticisms by slimming down Aunt Jemima’s image and making her younger. They also removed her bandana and replaced it with a headband.27 These changes satisfied some critics like William Raspberry, believing that they differentiated Aunt Jemima enough from slavery. According to Raspberry in 1977, “Aunt” and “Uncle” were no longer associated with slavery therefore, Aunt Jemima’s image was now innocuous.28 However, in a 1980 National Public Radio program, Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, a Black writer and culinary historian, announced Quaker Oats should retire Aunt Jemima indefinitely.29

In 1989, Aunt Jemima underwent her biggest change yet. Quaker Oats removed all head coverings, permed her hair, and gave her a pair of pearl earrings with the goal to make her look like a working, professional mom. Five years later, Quaker Oats tried to cement this pivot with a Gladys Knight campaign. The television advertisement showed the working African-American singer with her grandchildren eating pancakes. Additionally in the 1990s, the Aunt Jemima brand appeared to distance itself from its troubling past by partnering with the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) for the Women of Wonder award. The Aunt Jemima brand manager, Bob Hilarides, claimed that “Any of those negative implications [about Aunt Jemima] are so far in the past.”30 However, members of the Black community were still dissatisfied with the changes. Black founder and publisher of the Target Market News, Ken Smikle, said, “Remember Betty Crocker? Her picture no longer appears on Betty Crocker products. She’s been set free to pursue a career; Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben are still on duty in the kitchen.”31 In response to the 1994 advertisement, novelist Alice Walker claimed that Aunt Jemima couldn’t be updated because she was still rooted in slavery.32 Interestingly, many White consumers were content with Aunt Jemima’s image. However for most Black consumers, it was impossible not to see an enslaved woman on the box of pancake mix.33

Since 2016, Quaker Oats appeared to be more cognizant of Aunt Jemima’s brand and her impact. Dominique Wilburn, a Black woman, was hired as an Executive Assistant to create a rebrand campaign. Some of her suggestions included changing the name to “Aunt J,” depicting a woman with natural hair, building a different backstory that didn’t involve slavery, educating employees at a Southern plantation to teach them about the negative impacts of slavery, releasing a “contrite letter on the brand’s troubled history,” and avoiding advertisements and promotions of the Aunt Jemima brand.34

Even with Wilburn’s suggestions, the owners of her brand hesitated to act upon them and struggled to adapt. In 2001, PepsiCo incorporated Quaker Oats. In 2017, critics accused PepsiCo of trivializing the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement with a commercial starring Kendall Jenner. The commercial staged a protest of attractive young people holding reductive signs with sayings like “Love,” “Peace,” and “Join the conversation.” Meanwhile, Jenner, a White model, is shown nearby working on a photo shoot. Once inspired from an onlooking protestor, Jenner abandons her shoot, throws her model wig at a Black woman, and creates positive uproar when she offers a can of Pepsi to a police officer. The backlash was immediate. In response to this commercial, a New York Times article claimed Pepsi “[appropriated] imagery from serious protests to sell its product, while minimizing the danger protestors encounter and the frustration they feel.”35 Because of criticisms like these, Kendall Jenner and PepsiCo publicly apologized and the company pulled the commercial. As disastrous as this 2017 advertisement was, it laid groundwork for Aunt Jemima’s eventual retirement by demonstrating the conceptual disconnect between corporations and the realities of modern racial systemic problems.36

So, why did Aunt Jemima retire? Perhaps, simply her image is no longer profitable. For several decades, folks (usually Black) have criticized the image and refused to buy the Aunt Jemima pancake mix. However, this audience has been the minority until recently. And although the Kendall Jenner commercial was a fiasco, it wasn’t quite enough to flip the switch so Aunt Jemima could finally leave the kitchen. That didn’t happen until the Summer of 2020.

On May 25, 2020, Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, arrested and killed a Black man, George Floyd, for using a counterfeit bill at a convenience store.37 His death demanded, perhaps, one of the biggest social movements regarding race since the 1960s Civil Rights Era. But why? Because George Floyd’s murder was video recorded, Officer Chauvin’s actions were clearly unjust (even to those who previously turned a blind eye to police brutality). Social media distilled the video quickly and conversations surrounding the police’s treatment of Black people became viral, especially when considering Floyd’s death closely followed the killings of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery.38 The news of Floyd’s death also quickly spread because of the way the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown forced people to, first, pause from the distractions of “real” life. Second, out of safety, lockdown encouraged us to primarily use our online and digital communities to meet out social needs. And third, the traumatic mortality and financial experiences of a global pandemic increased our empathy towards racial injustice.39 Perhaps 2020 humbled each of us to consider our own vulnerability and to look outside of our race and class. According to Isaac Chotiner, “…the health of the most vulnerable people among us is a determining factor for the health of all of us, and, if we aren’t prepared to do that, we’ll never, ever be prepared to confront these devastating challenges to our humanity.”40 Overall, the timing of these murders, the incendiary nature of social media, and our unique attachment to our online communities at this time created a perfect storm: a storm that forced most of us out of our current frame of reference, and into a new one.

Floyd’s murder sparked worldwide protests and conversations centered on police brutality against people of color. In addition to conversations about police brutality, George Floyd’s murder sparked a renewed interest in “anti-racism,” a term coined by professor Ibram X. Kendi, which is the practice of pushing against conscious, and usually unconscious, racism within oneself and in societal systems.41 Throughout the rest of 2020, a larger audience began consuming anti-racist literature, supporting Black creators, businesses, and voices, and donating towards African-American nonprofits.42 Additionally, Floyd’s death demanded each of us to consider what organizations we support and what they represent in a racial context.

Because of a recently “enlightened” consumer base, leaders of businesses and corporations have also felt compelled to make changes in their structures and practices. For example, companies like Adidas have made public commitments to donate proceeds to BLM organizations or to consciously hire Latinx/POC people to their workforce. Other companies, like Nike and Twitter, declared Juneteenth an official employee holiday. HBO Max temporarily removed Gone With the Wind, the same movie mentioned earlier that assisted in cementing the “mammy” stereotype. Companies like Ben & Jerry’s and Warner Bros. Pictures have included resources like a guide to “Dismantle White Supremacy” or a free rental of the movie, Just Mercy, respectively.43

Obviously, these changes among businesses, and even among consumers, begs the question: is all of this performative? With the rise of a “Black Lives Marketing” approach, it presents a “dichotomy,” according an article by the Business & Human Rights (BHR) group: “On the one hand, a company may willingly recognize systemic and structural racism and commit to equality and diversity initiatives. But, it will do so without admitting its own failure to address racism and without any foundational or significant shift in their operations or approaches. In fact, few United States companies—if any—have tied their new commitments to diversity and inclusion explicitly to their responsibility for past human rights abuses.”44 It is difficult to sparse apart a company’s actions. And as long as money is involved, is it even possible to discern if a company is “sincere”? Maybe a more important question to ask is, does it even matter if a business is “genuine” if public accountability ultimately forces positive change?

In June 2020, shortly following George Floyd’s murder and coinciding with national protests, Quaker Oats and PepsiCo finally announced their decision to retire Aunt Jemima. In tandem, other companies like Cream of Wheat, Uncle Ben’s, and Land O’Lakes have also chosen to retire racist stereotypes. Many people, understandably unaware of Aunt Jemima’s history, were caught off guard by this company’s decision to move forward without their iconic character. However, the writing has been on the wall for some time.45

Executives at PepsiCo learned their lesson from the tone-deaf Kendall Jenner 2017 commercial and wanted to avoid another PR disaster. Despite a successful century and a half campaign with Aunt Jemima, she’s no longer a profitable asset, but a liability. Quaker Oats and PepsiCo can’t “repackage” her anymore. This became even more apparent when singer, Kirby Lauryen, created and released a viral Tik Tok video criticizing the brand. On June 17, two days after the video acquired 4.7 million views, Quaker Oats announced a name change and a plan to donate at least $5 million over the next five years to the Black community.46

Still, those who were surprised by Aunt Jemima’s retirement may think, “Are Black people just being a little too sensitive about Aunt Jemima?” Critics of the 1956 Springfield, Illinois NAACP also believed that the “drama” surrounding Aunt Jemima was frivolous or unimportant.47 But according to scholars A. Ward and Lorraine Fuller, “…it is more a matter of how people are included rather than that they have been included. Often, the images that Blacks see of themselves are either negative, offensive, or simply not there.” 48 The continual negative depiction of Black people, especially when it is disguised as harmless or benign, subconsciously affects how we interact and view Black people.

Furthermore, we ought to ask, “Who did Aunt Jemima benefit?” Nancy Green, the woman who played Aunt Jemima, tragically died when she was hit by a car in 1923, thirty years after her Columbian Exposition debut. Ironically, this woman who lived a very public persona, faded into obscurity after her death. Prior to 2020, there wasn’t even a headstone for Green.49 In another example, the descendants of Anna Short Harrington (another actress who played Aunt Jemima) sued Quaker Oats for the use of Green’s likeness. Their claim was denied and Quaker Oats asserted that Aunt Jemima was “neither based on, nor meant to depict any one person.”50 However, we can see from her actual history that this is not true. So, is it fair that Quaker Oats and PepsiCo benefitted so much from Aunt Jemima’s blackness when the “real” Aunt Jemima did not? Or what about the culinary contributions of actual enslaved women that have been co-opted by Southern White people? Is that fair?51

Aunt Jemima’s retirement signifies, although as a piece of a much larger puzzle, how marketing changes, how we remember the past, and what we expect of systems around us. One of the biggest things we can pull from the history of Aunt Jemima is how ordinary things in American history, like a pancake mix, are intertwined with complex social and racial issues. If we are unwilling to examine a box on a grocery shelf, what other parts of our American experience are we also ignoring?

I would like to thank M. M. Manring, whose book, Slave in a Box, guided much of my research. I would also like to thank Dara Tucker, who posted a viral Tik Tok video about Aunt Jemima and sparked my interest in Aunt Jemima’s problematic history. Public history isn’t limited to museums or long articles, but also in the important conversations we share with one another across multiple mediums. For that, I am especially thankful for Tucker’s contribution. I am also grateful for Black educators, such as Ibram X. Kendi and Ijeoma Oluo, who have willingly provided anti-racist resources. I look to their authority in how to be a better white ally. Please refer to their work for additional education.

- Aunt Jemima, “Our History,” Aunt Jemima, 2021, http://www.auntjemima.com/our-history; Tiffany Hsu and Maria Cramer, “Aunt Jemima To Be Renamed, After 131 Years,” New York Times 169, no. 58728 (June 18, 2020), B1. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 60, 62, 64; Aunt Jemima, “Our History,” Aunt Jemima, 2021, http://www.auntjemima.com/our-history. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 65. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 61, 67; Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (1995), 88. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 61. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 22, 66. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 11; Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (1995), 94-95. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 21; Lorraine Fuller, “Are We Seeing Things? The Pinesol Lady and the Ghost of Aunt Jemima,” Journal of Black Studies 32, no. 1 (September 2001), 123; Jennifer Bailey Woodard and Teresa Mastin, “BLACK WOMANHOOD: Essence and Its Treatment of Stereotypical Images of Black Women,” Journal of Black Studies 36, no. 2 (November 2005), 272; Cheryl Thompson, “‘I’se in Town, Honey’: Reading Aunt Jemima Advertising in Canadian Print Media, 1919 to 1962,” Journal of Canadian Studies 49, no. 1 (Winter 2015), 211-213; Maria St. John, “‘It Ain’t Fittin’.’,” Studies in Gender & Sexuality 2, no. 2 (Spring 2001): 131; Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (1995), 87–88, 89, 96. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 53; Maria St. John, “‘It Ain’t Fittin’.’,” Studies in Gender & Sexuality 2, no. 2 (Spring 2001),132, 134. ↵

- Toni Tipton-Martin, The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, Illustrated edition (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015), 39, 42; Ashley Rose Young, “Chef Lena Richard: Culinary Icon and Activist,” National Museum of American History, June 8, 2020,https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/lena-richard. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 21, 24. ↵

- Jennifer Bailey Woodard and Teresa Mastin, “BLACK WOMANHOOD: Essence and Its Treatment of Stereotypical Images of Black Women,” Journal of Black Studies 36, no. 2 (November 2005), 271; M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 8-9. ↵

- Tiffany Hsu and Maria Cramer, “Aunt Jemima To Be Renamed, After 131 Years,” New York Times 169, no. 58728 (June 18, 2020), B6. ↵

- Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (1995), 94-96. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 21; Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (1995), 89. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 74. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 75. ↵

- Cheryl Thompson, “‘I’se in Town, Honey’: Reading Aunt Jemima Advertising in Canadian Print Media, 1919 to 1962,” Journal of Canadian Studies 49, no. 1 (Winter 2015), 214; M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 21, 72, 74; Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (1995), 88k, 96. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 75-77, 124. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 81-84, 89; Cheryl Thompson, “‘I’se in Town, Honey’: Reading Aunt Jemima Advertising in Canadian Print Media, 1919 to 1962,” Journal of Canadian Studies 49, no. 1 (Winter 2015), 215, 220; Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (1995), 87–109. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 84-86, 88, 91-95; Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (1995), 87–109. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 95. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 95-108; Maxwell House Coffee, “Over this coffee the North and South pledged the new brotherhood years ago,” The Ladies’ Home Journal, January, 1926, 58. ↵

- Tiffany Hsu and Maria Cramer, “Aunt Jemima To Be Renamed, After 131 Years,” New York Times 169, no. 58728 (June 18, 2020), B6; M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 163; Jo-Ann Morgan, “Mammy the Huckster: Selling the Old South for the New Century,” American Art 9, no. 1 (1995), 87–109. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 153. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 155-157. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 165-168. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 171. ↵

- Tiffany Hsu and Maria Cramer, “Aunt Jemima To Be Renamed, After 131 Years,” New York Times 169, no. 58728 (June 18, 2020), B6. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 172, 177; Yumiko Ono, “Quaker Aunt Jemima Brand Hires Gladys Knight to Appear in Ads,” Wall Street Journal, Eastern Edition, September 16, 1994, sec. Marketing & Media; Analog Memories, Aunt Jemima’s Syrup (1994) Television Commercial – Gladys Knight – YouTube, accessed June 26, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q6bNjla7Jew; “Women of Wonder Contest Celebrates African-American Women,” New York Amsterdam News 92, no. 20 (May 17, 2001), 9. ↵

- Brent Staples, “Aunt Jemima Gets a Makeover: Still, History Dogs Her Steps,” New York Times, 1994, sec. EDITORIALS LETTERS. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 171. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 173; Cheryl Thompson, “‘I’se in Town, Honey’: Reading Aunt Jemima Advertising in Canadian Print Media, 1919 to 1962,” Journal of Canadian Studies 49, no. 1 (Winter 2015), 231. ↵

- Tiffany Hsu and Maria Cramer, “Aunt Jemima To Be Renamed, After 131 Years,” New York Times 169, no. 58728 (June 18, 2020), B6. ↵

- Daniel Victor, “Pepsi Pulls Ad Accused of Trivializing Black Lives Matter,” The New York Times, April 5, 2017, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/05/business/kendall-jenner-pepsi-ad.html. ↵

- Julian Sage, Kendall Jenner for PEPSI Commercial, 2017, https://vimeo.com/211751866; Daniel Victor, “Pepsi Pulls Ad Accused of Trivializing Black Lives Matter,” The New York Times, April 5, 2017, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/05/business/kendall-jenner-pepsi-ad.html; Tiffany Hsu and Maria Cramer, “Aunt Jemima To Be Renamed, After 131 Years,” New York Times 169, no. 58728 (June 18, 2020), B1, B6; Entertainment Tonight, “KUWTK”: Kendall Jenner Tearfully Apologizes for Pepsi Commercial: “I Genuinely Feel Like S**t,” accessed June 25, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0G9L9QKTSQM. ↵

- “Officer Charged with George Floyd’s Death as Protests Flare,” AP NEWS, April 26, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/fires-us-news-ap-top-news-ca-state-wire-mn-state-wire-e27cfce9464809aa8c91afd74c930bb5. ↵

- “Calls Grow for Probe of Shooting That Left Black Woman Dead,” AP NEWS, April 22, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/shootings-police-us-news-ca-state-wire-louisville-27bb910b0aa911bb6a04258195214a0a; “Father, Son Charged with Killing Black Man Ahmaud Arbery,” AP NEWS, April 20, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-shootings-us-news-ap-top-news-savannah-96990a5023927df289c934d2decd90b8. ↵

- Maneesh Arora, “Analysis | How the Coronavirus Pandemic Helped the Floyd Protests Become the Biggest in U.S. History,” Washington Post, accessed July 17, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/08/05/how-coronavirus-pandemic-helped-floyd-protests-become-biggest-us-history/.; Madeleine Schachter, “Black Lives Matter and COVID-19:,” The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion (IJIDI) 4, no. 3/4 (October 7, 2020), https://doi.org/10.33137/ijidi.v4i3/4.34638; Anna Marston, Eileen Scheir, and Shawna Pilout, “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Black Lives Matter Movement,” n.d., 1; F. S. Nakhaie and Reza Nakhaie, “Black Lives Matter Movement Finds New Urgency and Allies Because of COVID-19,” The Conversation, accessed July 17, 2021, http://theconversation.com/black-lives-matter-movement-finds-new-urgency-and-allies-because-of-covid-19-141500. ↵

- Isaac Chotiner, “How Pandemics Change History,” The New Yorker, March 3, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/how-pandemics-change-history. ↵

- Ibram X. Kendi, The Difference between Being “Not Racist” and Antiracist, 1591738592, https://www.ted.com/talks/ibram_x_kendi_the_difference_between_being_not_racist_and_antiracist. ↵

- Sanya Mansoor, “How to Support Racial Justice,” TIME Magazine 195, no. 23/24 (June 22, 2020): 40–41; Katie Couric, “A Detailed List of Anti-Racism Resources,” Medium, June 23, 2020, https://medium.com/wake-up-call/a-detailed-list-of-anti-racism-resources-a34b259a3eea. ↵

- Tiffany Hsu and Maria Cramer, “Aunt Jemima To Be Renamed, After 131 Years,”New York Times169, no. 58728 (June 18, 2020), B6; David Hessekiel, “Companies Taking A Public Stand In The Wake Of George Floyd’s Death,” Forbes, accessed April 27, 2021,https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidhessekiel/2020/06/04/companies-taking-a-public-stand-in-the-wake-of-george-floyds-death/; Ben & Jerry’s, “Silence Is NOT An Option,” accessed July 17, 2021, https://www.benjerry.com/about-us/media-center/dismantle-white-supremacy. ↵

- Erika George, Jena Martin, and Tara Van Ho, “Reckoning: A Dialogue about Racism, AntiRacists, and Business & Human Rights,” Washington International Law Journal 30, no. 2 (March 2021), 174. ↵

- Aunt Jemima, “Our History,” Aunt Jemima, 2021, http://www.auntjemima.com/our-history; Tiffany Hsu and Maria Cramer, “Aunt Jemima To Be Renamed, After 131 Years,” New York Times 169, no. 58728 (June 18, 2020), B1. ↵

- “Alumna Kirby’s Viral Video Helped Bring Down Aunt Jemima Brand | Berklee,” accessed July 18, 2021, https://www.berklee.edu/news/berklee-now/alumna-kirbys-viral-video-helped-bring-down-aunt-jemima-brand; Tiffany Hsu and Maria Cramer, “Aunt Jemima To Be Renamed, After 131 Years,” New York Times 169, no. 58728 (June 18, 2020), B6. ↵

- M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 165-168. ↵

- Lorraine Fuller, “Are We Seeing Things? The Pinesol Lady and the Ghost of Aunt Jemima,” Journal of Black Studies 32, no. 1 (September 2001), 121. ↵

- Sherry Williams, “Mrs Nancy ‘Aunt Jemima’ Green (1834-1923),” Find A Grave, accessed August 16, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/95732637/nancy-green; Linnea Crowther, “Finally, a Proper Headstone for the Original Aunt Jemima Spokeswoman, Nancy Green – Legacy.Com,” accessed September 7, 2021, https://www.legacy.com/news/culture-and-history/finally-a-proper-headstone-for-the-original-aunt-jemima-spokeswoman-nancy-green/. ↵

- “Dan Kedmey, “‘Aunt Jemima’ Family Demands $2 Billion Cut of Pancake Business,” Time.com, October 8, 2014; M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (United States of America: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), 77-78; Gwen Aviles is a trending news and culture reporter for NBC News, “Relatives of Aunt Jemima Actresses Express Concern History Will Be Erased,” NBC News, accessed August 12, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/pop-culture-news/relatives-aunt-jemima-actresses-express-concern-history-will-be-erased-n1231769; Bob Hallmark, “Family of Woman Who Portrayed Aunt Jemima Opposes Move to Change Brand,” https://www.nbc12.com, accessed August 12, 2021, https://www.nbc12.com/2020/06/19/family-woman-who-portrayed-aunt-jemima-opposes-move-change-brand/; Karu F. Daniels, “‘Aunt Jemima’ Descendants Upset Her Likeness Is Being ‘Erased from History,’” nydailynews.com, accessed August 12, 2021, https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/ny-aunt-jemima-family-members-fight-against-rebranding-20200622-frn67vaptvc4zizqf5eoqd5x4y-story.html. ↵

- Toni Tipton-Martin, The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, Illustrated edition (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015), 39, 42; Ashley Rose Young, “Chef Lena Richard: Culinary Icon and Activist,” National Museum of American History, June 8, 2020,https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/lena-richard. ↵

73 comments

Vanessa Preciado

Hello Carley, Just wanted to mention that the article was great, and packed with good information. It is amazing to me how many styles Aunt Jemima went through just to try to please a certain audience. I just read this article and found out that they sadly retired Aunt Jemima. I grew up seeing this in all the stores and in all my families kitchen’s, it was more like a comfort to me and my siblings. I have been laying off the pancakes for a few years so that is why I wasn’t able to notice more quickly, Im gonna go to H.E.B in a bit just to look at the box and see the change. In my opinion, I do think that African Americans are just hyping this racism thing up to much, I don’t believe that this women was on the syrup bottle to advertise her as a black slave, I say it is about the roots , the man who came up with Aunt Jemima was inspired by her and seen her as comforting, good food and hospitality, I just wish others would not always think on the negative. I love all the information and the images were nice as well.

Abigail Delarosa

First off, congratualations are your reward it was well deserved. Your article was very interesting and I enjoyed reading it I can see why you won. The journey of Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix throughout the years will always be one we will never forget. The article flowed very well and kept me intersted the whole and great use of sources.

Esteban Serrano

Hi Carly.

Such an informative article, indeed, so thank you for that! There was a lot that I learned by reading this, such as where the concept came from, and it’s actual ties into slavery. It’s also a bit weird to me considering I grew up on this brand. I remember the 2020 Black Lives Matter movements, and watching the live news coverage- all during a the outbreak of a pandemic. It was something of pure disgust, even knowing that what led to it. I was furious with that news story about Floyd, because I had always been taught to believe that police officers were to serve and protect. I think it was the one time in a while that America was extremely upset in two ways and became divided. The Aunt Jemima discontinuation was only an add-on to this movement, in which a lot was overdue for quite some time. Great article, and thank you for writing about such a cause!

Ryan Romine

This is a great article with even better research. I did not know that Aunt Jemima had such a history. I thought it was just a lady on a syrup bottle. But it has a deep history with one of the darkest times in our countries history with slavery. I think it is right to change the name but it is weird seeing the bottles without her on it. It was iconic.

Laura Poole

Incredibly written article! I loved how your points flowed so well and you made me get so invested in this topic. I loved your points towards the end arguing the statement that Black people were being too sensitive. It is so important to analyze how we are presenting all groups of people and change comes from small acts as well as large! Racism is Racism and anything that can be done to end it should be done. Loved your work, award well deserved!

Gabriella Parra

Your award is much deserved! This article is well written and well researched. I’m glad you made it easy for people to educate themselves on the issues of the Aunt Jemima brand from its inception to its present day consequences. It’s very valuable to look at the full history of the causes and effects of this stereotype, especially as someone who was unaware of them before. This is a great resource!

Alex Trevino

Phenomenal work. This article is probably one of if not the best I have read from this site, and I found all of your points to be incredibly clear, well thought out, and fits wonderfully along with the rest of the article. I, for one, found the comment made by Ken Smikle regarding Betty Crocker fascinating, as I completely forgot about Crocker’s image on her boxes, and the use of the comment is so well thought out, that I find myself completely unable to think of anything negatively noteworthy regarding it. Excellent job.

Sara Davila

I loved the introduction the author wrote. It hooked me into reading more about Aunt Jemma and why her name was being changed. I have never heard of this story and it was very interesting how this well known brand is connected to history. The aunt Jemima brand was founded under the impression that it would bring back the “old south”. Aunt Jemima was under the impression of a high ranked household slave that made delicious pancakes. Years later, this sprung a debate on whether the logo and name should be changed, however Black consumers wouldn’t imagine not to see her an enslaved woman.

Ruben Becerril

This article caught my attention as I basically grew up with the Aunt Jemima brand. I found it surprising that the brand has been around for 131 years and is still widely sold. I didn’t realize the amount of history this brand had, especially the controversies that came with it. I can tell that you put lots of effort into your research and checking for your source’s credibility.

Velma Castellanos

I loved your article. The more I kept reading the more I wanted to read what you wrote. I find it interesting because I never knew the history of Aunt Jemima because I like to cook much more than I should. Your resources are correct and your article is laid out well. The name and face of Aunt Jemima should have been taken down long ago and more people should read your article to understand why it was taken down.