After conquering a significant portion of the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army were determined to keep expanding their conquest into the heart of the Persian Empire. Since the beginning of his campaign, Alexander’s goal was to conquer the entire Persian territory. He was victorious battle after battle, but it was at Gaugamela that his military and strategic brilliance were truly put to the test. By the beginning of 331 BCE, Alexander and his formidable Macedonian army had already conquered important portions of the Persian Empire, including Anatolia, Egypt, and most of Phoenicia. The Persian king Darius III tried to use diplomacy in order to stop Alexander’s conquest, yet Alexander refused, and he assembled his Macedonian forces and began his march to Inner Persian.1

While on his way to Babylon, Alexander built a bridge using his experimented engineers in order to cross the Tigris River. His scouts captured Persian spies and reported the proximity of Darius’ army to the small town of Gaugamela, located near Babylon. Faced with a crucial moment, Alexander took a drastic decision and changed the direction of his army. Instead of besieging the important city of Babylon, he opted to engage Darius’ forces in a decisive battle marking the beginning of a battle that would shape the course of the Classical period.2

Alexander’s army established a camp close to the Persian camp to get ready for the battle; he wanted his soldiers to be well-fed, rested, and prepared for combat. On the other hand, Darius’ army and his troops were commanded to be alert at all times. His army was formed outside the camp throughout the night in fear of a possible Macedonian attack. While his army was resting at night, Alexander and his personal guard scouted the terrain and analyzed Darius’ army. Alexander realized that the new Persian Empire was not the same as what they faced a couple of years ago; now Darius’ army was larger with better and more disciplined heavy cavalry.3 The night before the battle, Alexander and his commanders met and discussed their tactics and strategies. According to Arrian, one of Alexander’s generals, Parmenion, advised for a night attack, thinking they would catch the Persians unprepared, but Alexander refused, arguing that he did not mean to steal a victory and wanted to have an open daylight battle, relying on his Macedonian army’s prowess rather than a surprise attack.4

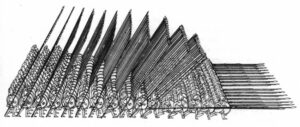

Knowing how the Persian army heavily outnumbered their army, Alexander and his commanders designed a specific army disposition. On the right wing, Alexander led the elite cavalry of Macedonian companions; the left wing was led by Parmenion, one of his most trusted generals; and in the center was the disciple and well-trained Macedonian phalanx. When dawn graced the day, Alexander, though overslept, emerged resplendent from his tent. With his helmet gleaming like refined silver, a Sicilian coat tightly bound, and a linen breastpiece as a relic from previous victories, a gorget adorned with precious stones encircled his neck. He clenched his belt, which was a Heliconian relic gifted by the Rhodians. His sword hung at his side; it was a blade gifted from the king of citizens. Finally, when he was ready for battle, his loyal companion, Bucephalus, a wild black horse that he tamed when he was a child, was ready to carry him throughout his most decisive battle ever.5

Before Alexander embarked on his Persian campaign, the Macedonian Empire was a peripheral state located in the north of Greece. Macedonian King Philip II marked the beginning of the Macedonian expansion throughout Greece, initiating a period of Macedonian military campaigns.

Thanks to his military mind, he implemented military reforms in the army, introduced the Macedonian phalanx, and transformed the Macedonian army into a professional and disciplined army.6 Recognizing the importance of diplomacy, Philip employed political maneuvering and alliances with different Greek city-states to secure peace and neutralize threats. A notable example of these maneuvers was the formation of the League of Corinth. This league was established to counter the possibility of an attack by the Persian Empire, which had invaded Greece multiple times decades ago. Through these diplomatic efforts, Philip succeeded in uniting Greek city-states under Macedonian leadership 7

Alexander, son of King Philip II and Queen Olympias, was born in 356 BCE. His father’s influence as a militant was significant. From the young age of eighteen, was already fighting battles alongside his father, distinguishing himself at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE, where he played a crucial role by leading a cavalry squad against the coalition of the Greek city-states army. Philip II introduced Alexander into military life and training in warfare, teaching invaluable training in warfare. In his early military career, he exhibited leadership qualities, showing bravery and competence that garnered profound respect from his soldiers. Additionally, he was also tutored in his adolescence by one of the greatest thinkers of ancient Greece, the philosopher Aristotle. Under his guidance, he received education in different subjects, including philosophy, literature, science, medicine, and ethics.8

His ascension to the throne was embarked by the tragedy of his father’s assassination in 336 BCE, as he became the Macedonian king at the age of twenty. Due to this event, a series of internal and external challenges occurred. He first started his consolidation among the Macedonian nobility by asserting his authority and eliminating any threats; then he subjugated the Theban revolt, which aimed to revolt against Macedonian rule, warning other Greek city-states about his power; and he secured the northern border of his empire against northern tribal groups. After securing internal and external threats, his ambition went beyond what his father’s vision was, conquering Persia. 9.

In 334 BCE, Alexander started his campaign by crossing the Hellespont, a waterway that connects Greece with Asia Minor. According to Arrian, Alexander crossed with 30,000 foot troops and 5,000 cavalry, and visited the tomb of Achilles in the ancient city of Troy to pay his respects, since he admired Homer’s stories.10 His first challenge that Alexander and his army faced was at the battle of Granicus. The battle occurred at the Granicus River, in which the Persian army doubled its number, composed of Greek mercenaries and Persian satraps. Alexander and his generals, Parmenion and Hephaestin, deployed his army with a phalanx in the center, cavalry and light infantry by the flanks. Alexander and his cavalry charges infringed heavily on the Persian army, and with the help of his Phalanx, victory was achieved 11 This battle marked an early success in his campaign, since it solidified his reputation as a formidable military leader.

Following his success at Granicus, Alexander had the new challenge of controlling the cities that were loyal to Darius on the Aegean coast. The cities of Miletus and Halicarnassus were important cities that challenged Alexander’s hegemony. It was the first time that Alexander and his army besieged fortified cities and the first time that he showed his adaptability to siege strategies. Ultimately, he managed to capture both cities and solidify his control and advancement in Asia Minor.

In 333 BCE, Alexander and Darius had their first encounter at the Battle of Issus. This clash was a pivotal moment in Alexander’s campaign to conquer the Persian Empire and prove his forces against Darius’ own army. As usual, Alexander had fewer forces than the Persian massive army but more experience from previous battles. Nevertheless, Alexander and his companion cavalry created chaos and significant damage to the Persian flanks while his phalanx was holding fearfully the center, and at one point in the battle, Alexander spotted Darius and decided to do a direct attack, making him escape while the Persian army was defeated. Alexander gained control of Darius’s camp after the battle; he captured the Persian’s immense wealth from his camp and Darius’ royal family. Even though it was his enemy’s family, Alexander treated Darius’ family with respect and honor, using them as a symbol to influence his presence in the region.12

After the Battle of Issus, Darius proposed a peace offer, promising the territories that he captured in exchange for the return of his royal family. But Alexander declined this offer and continued his conquest. Advancing by the region of Phoenicia, many cities surrounded Alexander, but the city of Tyre, a fortified city located on a rocky island offshore, refused Alexander’s request of submission, leading to tensions and making Alexander and his army siege the city in 333 BCE. Alexander lacked naval forces to Tyres naval forces, so he opted to build a mole in order to connect the mainland to the island. This process was brutal for Alexander’s engineers and army; the Tyrians launched multiple attacks, causing significant casualties and hindering construction progress. Eventually, Alexander received naval reinforcements from satraps. Throughout the siege, Alexander had more difficulties as weather conditions and fierce resistance from the Tyrans caused more difficulties. Finally, when the moles were done, Alexander launched a final assault that resulted in the total destruction of the city and a brutal sack, sending a message to other cities to surrender. 13

In 331 BCE, Alexander marched towards Egypt, where he and his army were received as liberators from the Persian subjugation. The Egyptian priest hailed him as a new pharaoh, establishing more control in the Egyptian region; he also founded Alexandria north of the Nile River, and reinforced his divine status by receiving the confirmation that he was the son of Zeus-Ammon by the Oracle of Amun. After securing his dominance in Egypt, Alexander continued his conquest of the Persian Empire. He and Darius would meet again after two years at Gaugamela, but this time it was the decisive battle for dominance over the Persian Empire.

The Battle of Gaugamela took place in 331 BCE. Different historians provided varying estimates of the number of soldiers from both armies. There has been a great debate among historians about the size of both armies. Modern historians agree that ancient historians exaggerated the Persian army size. Ancient sources suggest that the Persian army, at a high estimate, had around 1,000,000 infantry men, more than 45,000 cavalry units, 200 scythed chariots, and 15 war elephants. While modern historians estimate the Persian army had an army no larger than 100,000 soldiers, they suggest that it is not possible to reach a conclusion on the exact Persian number, but clearly it was a massive army that doubled or tripled the size of Alexander’s army with Greek mercenaries and heavy cavalry from different regions of Persian, estimating 100–150,000 soldiers, less than 60,000 infantry, around 35,000 cavalry, less than 200 chariots, and 15 elephants. Both ancient and modern historians agree on the size of the Macedonian army. Alexander’s infantry was around 40,000 soldiers, with men from Macedon, the Hellenic League, mercenaries, and light infantry from conquered regions, and 7,000 cavalry units.

At the battle site, Darius’ army stretched longer than Alexander’s flanks, with Mazaeus leading the Persian right wing, reinforced by cavalry units from Syria, Media, Parthia, Armenia, and other regions and Caucasian infantry as support. Bessus commanded the left wing, hosting heavy cavalry from nomadic tribes like the Sogdian, Arachosia, and Scythian. Darius positioned himself at the center with the elite Persian Immortals, Greek mercenaries, Indian cavalry, and formidable war elephants.14 Meanwhile, Alexander’s forces were meticulously organized; he deployed his experienced phalanx at the center and Thessalian cavalry led by Parmenion on the left flank. Alexander led the Companion cavalry from a position to the right, with the aid of quick skirmishers and hypaspists.15 His army was angled inward, anticipating a potential encirclement tactic by the Persians, with hoplites as the second line of defense. As the battle started, Alexander shifted his right flank to the right side of his army, prompting an outflanking maneuver. Bessus mirrored this move, stretching his flank toward Alexander’s direction and pulling Persian units away from their main army, creating a gap between the center and the Persian flank. Because of this shifting, the gap between the Persian center and left wing widened.16

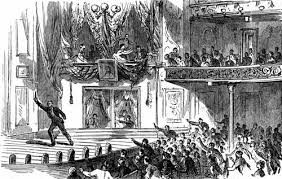

In response, Bessus launched a direct attack on Alexander’s right flank, a maneuver anticipated by Alexander. While the right side clashed, Darius and Mazaeus engaged the rest of the Macedonian forces. Mazaeus’s heavy cavalry targeted Parmenion’s outnumbered left flank, causing intense fighting. Darius, attempting to break the Macedonian center, dispatched his chariots. However, the Macedonian phalanx skillfully countered, parting lines and utilizing missile support from the Agrianian infantry to neutralize the chariot threat. After a failed chariot attack, Darius sent most of his right center to charge the Macedonian center. The Macedonian phalanx center was split in two; the left-center would hold Darius’ infantry attack, while the right-center would push directly into Darius’ location. Recognizing a vulnerable point in Darius’s center, Alexander took action. As his right-center fought fiercely against Darius’s forces, Alexander launched a decisive charge, exploiting the weakened gap in Darius’s left-center. Closing in on Darius, the Persian center collapsed, and as chaos started in the Persian center, Darius fled the field. As Alexander noticed Darius fleeing, he was about to begin a chase, but a messenger from his left flank alarmed him about the Parmenion side starting to crumple, and Alexander faced a crucial decision. Despite the opportunity to seize Darius and end the Persian empire, he prioritized his general’s struggle, turned back his units charging against Mazeus Persian cavalry, and saved Parmenion.17

As the second Persian army was crushed, Alexander was victorious. On the fields of Gaugamela, Alexander won the decisive victory after a battle that featured tactical brilliance and strategic maneuvers. Alexander and his army continued marching, reaching Babylon, where the city surrendered peacefully and welcomed him and his army. Even though Gaugamela was not the last battle he fought for his conquest of the Persian Empire, it was a battle that showed his brilliant skills in battle and his determination to keep expanding the Macedonian empire. To this day, the battle of Gaugamela is considered one of the most important battles in history, due to its strategic complexity, innovative tacting, and the deep shaping of culture development in multiple regions.

- Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander; or, The History of the Wars and Conquests of Alexander the Great, Translated by Edward James Chinnock (London: Hodder and Stroughton, 1884), Book II. Chapter XVI, 117. ↵

- Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander; or, The History of the Wars and Conquests of Alexander the Great, Translated by Edward James Chinnock (London: Hodder and Stroughton, 1884), Book III. Chapter VII, 152. ↵

- Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander; or, The History of the Wars and Conquests of Alexander the Great, Translated by Edward James Chinnock (London: Hodder and Stroughton, 1884), Book I. Chapter XIII. ↵

- Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander; or, The History of the Wars and Conquests of Alexander the Great, Translated by Edward James Chinnock (London: Hodder and Stroughton, 1884), Book III. Chapter X, 159. ↵

- “Plutarch’s Alexander,” Junior Scholastic (October 31, 2005), T-6(2). Gale General OneFile (accessed November 16, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A138538075/ITOF?u=txshracd2556&sid=bookmark-ITOF&xid=5bd03517. ↵

- Edward M. Anson, “The Hypaspists: Macedonia’s Professional Citizen-Soldiers,” Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte 34, no. 2 (1985): 247, https://www.jstor.org.blume.stmarytx.edu:2048/stable/4435923. ↵

- Peter Green and Eugene N. Borza, “Philip of Macedon,” in Alexander of Macedon, 356–323 B.C.: A Historical Biography, 1st ed. (University of California Press, 2013), 27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt2855mn.10. ↵

- “A bold, brilliant study of Alexander the Great’s early life; BOOKS,” Sunday Telegraph (London, England), April 3, 2022, 27. ↵

- “Alexander the Great, the military genius,” Egypt Today, June 14, 2022, NA. Gale General OneFile (accessed November 16, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A707104870/ITOF?u=txshracd2556&sid=bookmark-ITOF&xid=8c9d9f18 ↵

- Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander; or, The History of the Wars and Conquests of Alexander the Great, Translated by Edward James Chinnock (London: Hodder and Stroughton, 1884), Book I. Chapter XI, 36. ↵

- G. T. Griffith, “Alexander’s Generalship at Gaugamela,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 67 (1947): 78, https://doi.org/10.2307/626783 ; A. M. Devine, “Demythologizing the Battle of the Granicus,” Phoenix 40, no. 3 (1986): 267. https://doi.org/10.2307/1088843. ↵

- Henry M. de Mauriac, “Alexander the Great and the Politics of ‘Homonoia,’” Journal of the History of Ideas 10, no. 1 (1949): 110, https://doi.org/10.2307/2707202 ↵

- Jehan Wauquelin and Nigel Bryant, “The Siege Of Tyre,” in The Medieval Romance of Alexander: The Deeds and Conquests of Alexander the Great (Boydell & Brewer, 2012), 58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt1x73gh.8. ↵

- Donald L. Wasson, “Battle of Gaugamela,” World History Encyclopedia. Last modified February 27, 2012. https://www.worldhistory.org/Battle_of_Gaugamela/. ↵

- A. M. Devine, “Grand Tactics at Gaugamela,” Phoenix 29, no. 4 (1975): 374, https://doi.org/10.2307/1087282 ↵

- Minor M. Markle, “Macedonian Arms and Tactics under Alexander the Great,” Studies in the History of Art 10 (1982): 90, https://www.jstor.org.blume.stmarytx.edu:2048/stable/42617923 ↵

- Minor M. Markle, “Macedonian Arms and Tactics under Alexander the Great,” Studies in the History of Art 10 (1982): 91, https://www.jstor.org.blume.stmarytx.edu:2048/stable/42617923 ↵

1 comment

Mila Cordero

En la Batalla de Guagamela era una oportunidad para Alejandro el Grande a usar su método y flexibilidad. Enseñó una buena disposición a mirar armada de los persas cuando fui a pelear con fuerza de Darius. Planeado para atacar en la noche porque sabían qué el oponente era formidable. Alejandro tenía mucha seguridad y lo puedes ver porque si estaba peleando en el día y no con el cubre de la noche. Éste artículo también da una historia del Macedonio bajo el Rey Philip II.