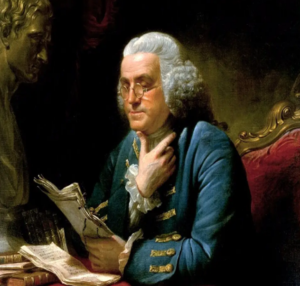

After the last shot had rung of the American Revolution and the white flag of surrender was waived by General Charles Cornwallis, the prolonged struggle for independence finally concluded. As the battlefields emptied, government buildings and political meeting places began to fill, and the genesis of a new country had begun. At the forefront of this creation were the founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin being one of them. During these humble beginnings of early America, the founding father Benjamin Franklin stationed himself on the front lines preparing to create a country unlike any other before it. This influential American icon found himself amid countless early Republic feats, such as the Constitutional Convention, in which he sat, providing insight and educated opinions that ultimately led to the creation and ratification of the United States Constitution. He also pioneered his way into international relations as a diplomat through his involvement in the negotiation of the Treaty of Paris. Benjamin Franklin was constantly finding himself at the forefront of early American politics and diplomacy. Expertise in both of these roles required extensive documentation and thorough reading. During the pinnacle points of his political and diplomatic quests, Franklin was in his early eighties and needed spectacles in order to sustain the writing and reading demands of these roles. He constantly found himself in political meetings, diplomatic travel, and social events, where Franklin stated that he would utilize, “two pairs of spectacles, which I shifted occasionally as in traveling I sometimes read and often wanted to regard the prospects.”1

Benjamin Franklin utilized late eighteenth-century corrective lenses that were separated between two types of spectacles: concave lenses for far sight, and convex lenses for near sight. The separation of these two lens types caused Franklin to be constantly switching between spectacles, which left him irritated and annoyed. Franklin voiced his opinion on this quality-of-life issue in a letter to a friend stating that he was always, “finding this change troublesome, and not always sufficiently ready.”2 This newfound quality of life issue, owing to Franklin’s failing eyesight, would permit him to initiate an optical revolution that would change corrective eyewear forever.

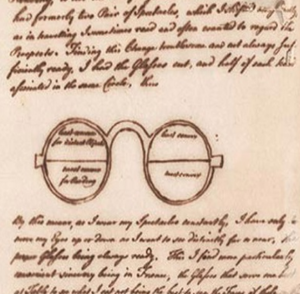

When Franklin was not busy with politics and diplomacy, he would delve into scientific works and novel feats of creativity. These pastimes provided Franklin with a skillset based on curiosity, critical thinking, and innovation. His mind was the breeding ground for life-changing ingenuity and groundbreaking works. He would use his cognitive strength to find solutions to problems from politics to stopping lightning-induced fires. If anyone was able to find a solution to corrective lens inadequacies, it would be him. Being fed up with eighteenth-century eyewear, Franklin decided to take the future of corrective lenses into his own hands. He began by sitting in his residence in Philadelphia and brainstorming what ways he could solve this optical dilemma. In searching the inner recesses of his mind for an answer, he began with the basics of his issue, being the two separate spectacles. Franklin came upon a solution: somehow combine the two spectacles into one. This idea sparked his innovative breakthrough in eyewear. He then immediately manifested his thoughts into reality through sketches and written explanations on these new glasses. The sketch presented the alternative to using two separate lenses in two sets of spectacles; instead, he would combine both lens types together. He did this by sketching a pair of spectacles with lenses constructed of one-half circle of a convex lens and one-half circle of a concave lens on top of each other. He then oriented the lens types so that the half circle placed on top was convex for far sight, since this kind of viewing is done most, and the bottom half circle being concave for near sight, since the head tilts downward naturally when reading. After configuring the design of the new eyewear, he gave them the appropriate name of double spectacles, due to their design. Although it is not well documented, he felt confident in his sketch of the double spectacle. It is said that Benjamin Franklin proposed his idea to a professional in the optics business for consultation on the efficiency and practicality of his innovation. In a letter, Benjamin Franklin wrote after talking to an optical professional, “By Mr. Dolland’s saying, that my double spectacles can only serve particular eyes I doubt he has not been rightly informed of their construction.”3 He took this critique in mind with his final sketch design and began tinkering with his own two pairs of spectacles.

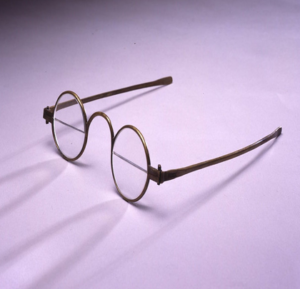

He went into the design process with a strong understanding of the technical and classical knowledge of how lenses worked in regard to sight and vision needs. Being well-versed in the contrasting lens types and the way glasses were made, he decided to carefully craft his vision from paper into a prototype. Utilizing his own spectacles, he found his precise prescription for both his convex and concave lens types, then made them into half circles, then heated them onto each other to create one cohesive circular lens. He then inserted this ingenious lens design into his spectacle frames and created the revolutionary invention: the double spectacle. These new lenses were Benjamin Franklin’s new everyday glasses. He took them everywhere he went, and quickly realized how much of an impact they had made on his quality of life. Franklin quickly came to like his new invention saying, “by this means, as I wear my spectacles constantly, I have only to move my eyes up or down, as I want to see distinctly far or near, the proper glasses being always ready.”4 He even reported his double spectacles playing a large role in his diplomatic career, stating, “when one’s ears are not well accustomed to the sounds of a language, a sight of the movement in the features of him that speaks help to explain; so that I understand French better by the help of my spectacles.”5

Almost in every area of his life, Franklin was seeing this seemingly simple invention make an impact. From being able to just move his head to access distance or near vision, to improving his abilities in diplomatic endeavors, his simple invention was more of an asset than he expected it to be. These new spectacles allowed Franklin the ease of life necessary to improve his professional and personal endeavors. Benjamin Franklin’s quest for knowledge and innovation was almost always free to the public. Very little of his works and innovations were patented or kept from public domains. He was a large supporter of education and the dissemination of information to improve society. Franklin was so open to providing others with his new design that “while in Passy, outside Paris, he described (i.e bifocal) double spectacles in a letter, dated 21 August 1784, to his ‘Dear Old Friend,’ the philanthropist, George Whately.”6 Encompassed in the letter he even replicated a detailed drawing of the double spectacles to his friend based on his final sketch. This act completely gave away the concept and design of his bifocals in order to provide his friend with the ease of life he had provided himself. Franklin even urged his friend to publish the invention by saying, “I send you herewith the sketch I promis’d you. Perhaps it may be of use to publish something of the kind.”7

Benjamin Franklin used his invention to help those he cared about, as he did with most of the inventions he created. He didn’t try to advertise his inventions, but instead provided insight into how to make them and use them to better society as a whole. Benjamin Franklin’s ingenious spectacle design completely reshaped eyewear and was one of the many reasons he is known today as an iconic figure in American history. In inventing the double lenses, he created a new form of eyewear that has ever since been used, even to this day; and we now call them bifocals. Since their creation, they steadily increased in popularity to the point where they almost completely replaced the old way of making two separate spectacles. To this day adults over the age of forty all over the world use bifocals. These glasses are the preferred eyewear of choice for the same reason Benjamin Franklin made them in the first place. Recent technologies have implemented advancements to Franklin’s double spectacle design, such as improved stability between the separated lenses in order to keep them from falling apart. Another new advancement towards bifocals is called progressive lenses, which completely eliminate the lines between the separate convex and concave lenses. These new impacts on eyewear would not have been done without the genius and ingenuity of Benjamin Franklin. His impact on early American politics from the domestic stage to international and the technology in early America is unmatched. His vision for a greater America wasn’t just in attending the Constitutional Convention or international diplomacy, but in the advancement of technology and innovation. Benjamin Franklin shows that critical thinking and creativity birth innovation, which allowed him to leave a legacy of high stature and esteem.

- Nathan G. Goodman, ed., “Front Matter,” in The Ingenious Dr. Franklin, Selected Scientific Letters of Benjamin Franklin (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1931), i–iv, 54-55. ↵

- Albert Henry Smyth, The Writings of Benjamin Franklin Collected and Edited With a Life and Introduction (Alpha Edition, 2020), 337-338. ↵

- Lee Ann Potter, “From Inconvenience to Inspiration,” The Science Teacher 86, no. 1 (August 2018): 60. ↵

- Nathan G. Goodman, ed., The Ingenious Dr. Franklin, Selected Scientific Letters of Benjamin Franklin (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1931), i–iv, 54-55. ↵

- Nathan G. Goodman, ed., “Front Matter,” in The Ingenious Dr. Franklin, Selected Scientific Letters of Benjamin Franklin (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1931), i–iv, 54-55. ↵

- John R. Levene, “Benjamin Franklin, F.R.S., Sir Joshua Reynolds, F.R.S., P.R.A., Benjamin West, P.R.A. and the Invention of Bifocals,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 27, no. 1 (August 1, 1972): 141–142. ↵

- Nathan G. Goodman, ed., “Front Matter,” in The Ingenious Dr. Franklin, Selected Scientific Letters of Benjamin Franklin (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1931), i–iv, 54-55. ↵