In late-March 1969, professors, activists, School Board members, and education experts flocked to a room at the Gunter Hotel in San Antonio, Texas on a Spring weekend as the end of the school year approached. The Bureau of Educational Personnel Development and St. Mary’s University sponsored this two-day conference. At this conference, attendees discussed ideas for a long-term educational plan for Mexican American students in Texas. This plan brought together ideas and voices not only from the School Board and local teachers but also from Mexican American grassroots activists.

Educators and community leaders were excited about this conference and felt that this was the first time their ideas and troubles would be heard widely. Up to this point, many professionals in the field of education had not seen any use for bilingual and bicultural education. For many public schools, it was believed that this method of education would hinder children’s integration into American Society. Despite these national hesitations, more people than expected showed up the first day of the conference, flooding the event space. To many, this would be a major victory in beginning conversations about how to teach and implement bilingual and bicultural education in U.S. schools.

The conference drew on texts not only from prestigious organizations but also from personal letters from those whom this meeting could affect the most. Organizational texts included one by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights entitled, “The Education of the Mexican-American in Texas, the Challenge, the Conscience of the State,” and the report from the National Advisory Board to the U.S. Office of Education the Mexican American Affairs Unit, “Mexican-American Quest for Quality.” Included among these official documents and prestigious speakers, there was a letter written by a young man in 1969 who had experience with the education system as a Mexican American. He wrote about how these schools made him feel as if he, his culture, and his language were not important. He wrote, “I see that because I am a Mexican-American and I have a language barrier, a lack of cultural identity and have received an inferior education.” Stories like this were all too common throughout the United States in areas that were plentiful with Mexican American immigrants and their children.1

In 2019, fifty years after this historic conference concluded, a woman who was a student in the Edgewood education system when this conference took place interviewed with me. Both the letter referenced above and this woman’s interview fifty years later show disappointment in the educational system that existed for Mexican Americans in the the late-1960s.

During 1968 very few educational programs used Spanish in a bilingual setting, and of these, most allowed only the use of “Textbook Spanish.” This term means that the language needed to be grammatically correct, and, in many instances, needed to use Spanish derived from Spain rather than Mexican Spanish or colloquial Spanish. I have given my interviewee a pseudonym to protect her privacy.

My interviewee, who I will call Mary, reminisces on this idea of Spanish in schools at the beginning of her interview. She went to grade school in the Edgewood District, and was told by teachers that she was not allowed to speak Spanish within school grounds. Her family decided that it was best if she was not taught the Spanish language and was unable to connect with that side of her culture. As a young girl, Mary went through her elementary and middle school classes speaking only English inside the classroom and her school campus. In high school that changed. When she went to her classroom and sat down at her seat, she was informed that her school was adding a new language credit. Still, it was not until the end of her school career when she could take Spanish as a language.2

Unlike other schools in affluent districts who had the opportunity to learn Spanish as an elective years before then, these language classes were new to her district and something that she had never experienced before. She was excited initially and felt it to be something that supported her diversity as a bicultural student. However, when she got to know more about the class from her teachers, she realized this Spanish was not the Spanish she knew, but a dialect from Spain, a country across the ocean. Mary felt her district was disingenuous in wanting to offer a learning opportunity about her culture and life as a Mexican American.

In 1968 the average educational level completed by Mexican Americans in the United States was 6.3 compared to the national average of 11.2. At this time 89 percent of children with Spanish surnames in Texas would not graduate from the 12th grade. These numbers showed the limitations of Mexican American education in Texas at the time. These graduation rates were not helped by standardized tests that were only distributed in English. During this time, close to 58 percent of students in San Antonio Independent School District (SAISD) were Mexican American while only a fraction of teachers within the district were Mexican American. Of these teachers who are distributing the standardized tests, only 10 percent had Spanish surnames. This information shows that there were large amounts of misconnection and miscommunication between teacher and students im the classroom, which resulted in lower test scores and lower education levels.

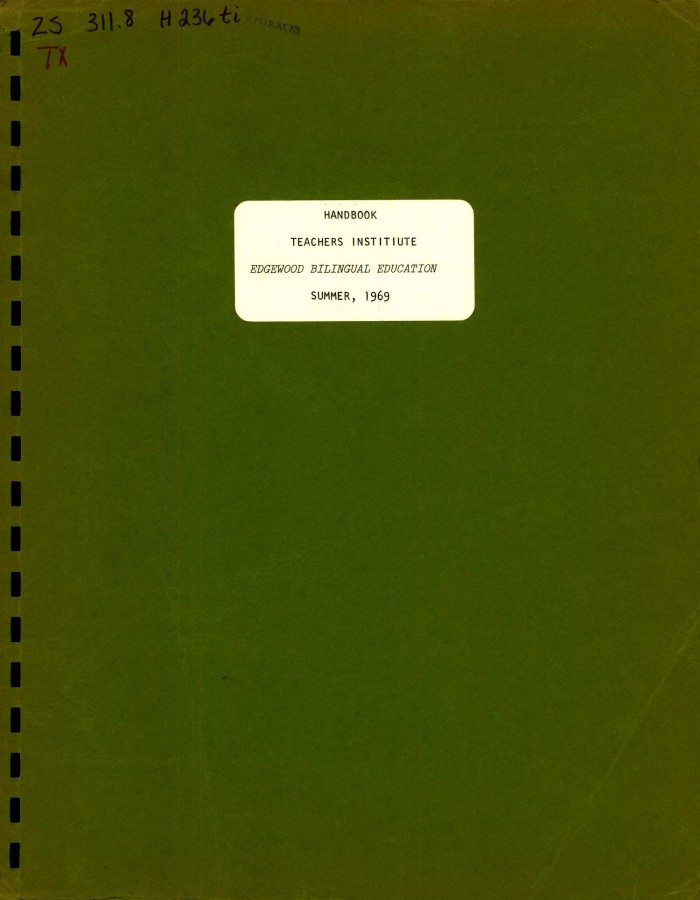

In the summer of 1969, the Teachers Institute created a handbook for “Edgewood Bilingual Education.” It stated, “Teachers may thus comprehend the social changes occurring in their environment and consequently find themselves more capable of guiding bilingual children through the social, psychological, and emotional adjustments which arise in the transfer from the Agricultural-Mexican culture to the values of an Industrialized U. S. Culture.”3 This is significant because it shows that this national organization believes that bilingual and bicultural students still needed to conform to U.S. values.

Mary, in her interview, speaks highly of her teachers throughout all her years of grade school education. She really remembers her teachers in a positive light. Her teachers were there for the students even though they had very few resources and even lower pay.

When she entered Trinity University, she remembers being asked in her first math class her exposure to different math topics in high school. Everyone one else in her class, all who were from more affluent districts answered Calculus, Statistics, and other more complicated subject areas. Mary was only allowed to learn up to Pre-Calculus in her high school. In addition, her Pre-Calculus class had been a mixture of cheerleaders, football players, students in the marching band, and others whose extracurricular would take them away often. Many students did not have the confidence to take the course and those who did would be gone regularly. Mary’s high school class was small, and due to all the absences, class would be canceled most days. At times she felt robbed of her education when she looks back.

Mary recalls that the construction of a new Edgewood school that she would attend disrupted her studies. She went to school across the way in the remnants of stores that were used as makeshift classrooms. She and her friends had hope and anticipation for the new school. Due to having to use a temporary school with little room, most days were only three class periods long. Mary remembers the sound of a loud cowbell being flung up and down by her principal. This cowbell should have been around the neck of a grazing cow, but instead it turned into her cue to go on to her next class.

The construction of Hemisfair Park began at the end of 1965. The World’s Fair held in San Antonio within Hemisfair Park began in the early months of 1968. This was a time for San Antonio to shine with a new sprawling 96-acre park. Over six million people would visit Hemisfair Park during the 1968 World’s Fair. During its construction, multiple iconic buildings were built as well, including the Institute of Texan Cultures, the Convention Center, and the Tower of Americas. Hundreds of hours of manual labor were needed to construct these building before the World’s Fair convened.4

At the same time that construction was underway for what would mark San Antonio as a tourist city, Mary was sitting in her makeshift classroom waiting for the construction on her school to be finished. She explained that most of the good construction workers decided to work at Hemisfair Park, and so the school struggled to find workers to finish building it. Because finding labor was so difficult in San Antonio at the time, the work on the school was rushed. Still, Mary was excited to see how it would turn out. After the construction concluded the faculty asked the students if they would all pick a desk from their temporary school, and take the desk that they had chosen and carry it across the way to their brand-new school. Students of all grades grabbed their desks and slowly together inched their way and their belongings to their brand-new school.

Reflecting on her past years later in this interview, Mary sees the reasoning behind the end result of how her school building turned out. The school was new, but it was noticeably rushed in the construction. Yet, she and her classmates were still excited that they could be out of that makeshift room and into a real classroom. Despite this makeshift education, Mary later graduated from Trinity University. She would go on to receive a Doctorate Degree in her later years. Throughout Mary’s interview, she smiled, cried, and fumed in anger about her life, and yet still, she had found her calling. Working with animals, Mary feels that like her in many instances, they have not had a voice.

2019 is the 50th anniversary of the San Antonio conference, “Bilingual, Bicultural Education. Where Do We Go From Here?” As of 2019, still only 74 percent of Latinos in San Antonio graduate from high school. Only 15 percent of most Hispanics living in San Antonio have received a bachelor’s degree. Since 2018 43 percent of households in San Antonio speak a language other than English. A Washington based group called the “Dual Language Learners National Work Group” has commended San Antonio for their dual-language initiatives. Life stories like Mary’s reflected the need for more sources in education for Mexican-American students before and after the 1968 San Antonio Conference.5 6

Presently San Antonio is working hard to create these resources for Mexican-American children. Yet, there are instances when an imbalance of educational resources is evident. Through Mary’s interview, we can understand bilingualism and the bicultural education of Mexican American student a little bit better and how we as citizens of San Antonio can make a difference.

- Ernest M. Bernal, “The San Antonio Conference. Bilingual–Bicultural Education—Where Do We Go From Here?” St. Mary’s University, San Antonio, Texas, March 28-29, 1969. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED033777. ↵

- **Mary** (name changed for privacy), interviewed by Danielle Garza at San Antonio Earth Day in Woodlawn Park, 2019. ↵

- “Handbook Teachers Institute: Edgewood Bilingual Education Summer, 1968.” Accessed May 2, 2019. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth639478/m2/1/high_res_d/UNT-0020-0041.pdf. ↵

- “History of Hemisfair,” Hemisfair, July 28, 2015, https://hemisfair.org/visitor-information/history/. ↵

- Conor P. Williams, “Dual Language Learners National Work Group,” n.d., 52; U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts, Accessed May 2, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/sanantoniocitytexas ↵

- “San Antonio, Texas Population 2019 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs),” World Population Review, Accessed May 2, 2019. http://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/san-antonio-population/. ↵

27 comments

Rahni Hingoranee

Latin American culture is so prominent in Texas and San Antonio, specifically, so this article is relevant. I think it is interesting to find out that our university was involved in making bilingual education more prominent in San Antonio. The discrimination Mary faced should not be faced by anyone, which is why I am glad more steps in the past fifty years have been taken to try and stop this. It is best to educate people in general.

Isabella Torres

This is the first article I have read that included an interview; I found it to be very interesting and a great way to convey the messages that needed to be conveyed. This article made me further appreciate how bilingual education has progressed within the past fifty years. Although I am not bilingual, I know a great number of people have been affected by the progress made within their eduction. It is so important to have a good bilingual program because instances such as the discrimination Mary experienced should not be happening today; every person should have equal opportunities when it comes to education.

Courtney Pena

I thought that this was a unique article mainly because it involved an interview with someone who was impacted by the educational resources that Mexican American children had at the time. This article showed the challenges that bilingual people faced. I thought that it was interesting how when Mary went to college, she realized that her peers took advanced math while she did not. People need to realize that education is important for everyone to have in order to succeed in life.

Charli Delmonico

This article really brought to light how difficult life was for bilingual and bicultural students growing up in Texas where such classes were not taught or encouraged. I am honestly surprised and upset at the lack of resources Mary and many other young students like her had. I’m glad her new school was built, despite the construction issues that accompanied it, but there are many more bilingual students who don’t have access to an education that will allow them to go far in life and pursue their passions in life.

Nicole Ortiz

Reading this article just made me realize that although it was easy for me to grow up as a student who was bilingual, that wasn’t always the case for others. I remember in elementary, i would have to take a test at the end of each school year to see if my english was improving and i don’t think it was until 5th grade that i was finally told that my english was good enough to where i didn’t have to be tested anymore all because i spoke Spanish at home and grew up speaking the language. If it was hard for me just to do that, I can’t imagine how difficult it was for Mary to try and receive an education but couldn’t and if anything was robbed from it. But despite all of the difficulties that she faced, i was so happy to read that she had eventually received her Doctorate degree years later

Elisa Nieves

I always feel so fortunate when I read stories about people who suffered from the wide spread discrimination towards latinos, specifically people who from hispanic decent like I am. Growing up, I was taught Spanish at home and English at school. My bilingualism was never looked down upon and my Spanish was never conformed to what schools wanted and knowing that this was something that others went through before me makes me feel very grateful that I didn’t. It’s hard knowing that part of you isn’t accepted by society or that it would only be accepted if it’s conforming to something foreign to you, like how Mary’s Spanish was comforted by Spain’s Spanish because that’s how schools taught it.

Kasandra Ramirez Ferrer

I love when people write about articles who involved Latin America culture and how as time goes by it’s been included in schools. However, even though is not Spanish I think it’s important to include at least a bilingual program in its system, it allows students to expand their skills and education and culture which it opens a lot of doors for career opportunities. If schools implement these programs, it also gives them a bigger chance to grow and be different from other schools.

D'Hannah Duran

I attended SAISD schools from elementary to high school and I know my schools always had an option for students that knew Spanish as their first language to learn English while still speaking Spanish. To think of a time where there wasn’t an option like this is a little upsetting, that students who may not have had family that spoke English for them to help therefore the were able to graduate high school. I am glad that there have been changes that have made school more bicultural, because it shows that the world we live in not everyone speaks the same language and we have to understand/help each other.

Elizabeth Maguire

This article really made me reflect on the importance of bilingualism, especially for a local country like Mexico. It made me think about how many opportunities knowing a second language can give. This article also really emphasizes the key points faced by Mexican American students and those wanting to understand another language better in the educational system.

Kelsey Sanchez

Reading this article connected with a story of one of my family members. I remember one of my cousins was not entitled to speak Spanish, but education was the important thing. Bilingual programs in school should be kept in schools, whether it is elementary, middle or high school. I feel like this will help people gain other opportunities for them such as in jobs. This article represents good information of how bilingual and bicultural education came about in the United States schools.