Running outside, chasing your friends, playing with Legos–these are things you might remember doing as a young child. However, from the late 1700s to the mid-1800s in Britain, being paid meager wages and working for as much as sixteen-hour days with dangerous mining equipment was the norm for many young, British children. During the Industrial Revolution this was an ugly reality. Many working-class families found it necessary to have their children work alongside them in the mines. Because of their size and cooperation, and because it was easier to pay them less, these children were paid about five times less than men for the same number of hours worked, which for these young miners could be up to fourteen-hour days.1

Before the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842, children as young as four were allowed to work in the mines.2 Just imagine such young children running around a dark coal mine–it simply does not sound safe at all. These children were hired to be able to get into those hard to reach places that fully grown adults were unable to get into. During the Industrial Revolution, coal was a major source of energy, and was extremely important because it burned hotter than wood charcoal. The primary use of coal was used as a source of energy, and used to power the steam engines of factories, where many other children also worked. Because of its high demand and necessity, it helped increase jobs for the working people. Because of these factories, major industrial cities such as Birmingham, Manchester, and Liverpool, grew at a fast pace from small villages into large cities.3

In British coal mines, children typically had one of three jobs. Trappers, typically the youngest, would open and close the wooden doors–also called trap doors–to allow fresh air to flow through the mine. These trappers would sit in darkness for almost twelve hours at a time. It may seem a simple task, but if one of these little ones fell asleep, the job could become very dangerous. Other jobs were the tasks of hurrier and thruster. These jobs were usually given to older children and women. These workers had to pull and push tubs that were full of coal along the roadways, all the way to the pit bottom. The hurriers would be harnessed to the tub, and the thrusters would then help hurriers by pushing these tubs of coal. The thruster would have to push tubs of coal weighing over 600 kilograms from behind with their hands and the tops of their heads. The thrusters, mainly older girls, had to carry these baskets of dug coal, which were much too heavy for them. Because of their heavy weight, it would then cause their young, growing bodies to develop with deformities. The last typical job was the getter. This one was typically assigned to the oldest and strongest, usually grown men or strong, older teens. This job required them to work at the coal face, cutting the coal from the seam with a pickaxe. This was typically the only job where they would use a candle or safety lamp for light, as cutting the coal required it.4 Although the work at the coal mine may not seem very difficult, it was very dangerous. In one unnamed coal mine, 58 of the total 349 deaths in one year involved children thirteen years or younger.5

Those who worked in coal mines–whether below or above ground–were exposed to life-threatening working conditions that could ultimately be detrimental to their health. Children, mainly boys as young as eight, worked as breakers. Here, the coal was crushed, washed, and sorted according to size. The coal would come down a chute and along a moving belt. These breaker boys would work in what was called the picking room. Here, they would work hunched over for ten hours a day, six days a week, sorting the rock and slate from the coal with their bare hands. If their attention even drifted for a second, they could lose a finger in the machinery.6 The work also resulted in their exposure to a large amount of dust. In some cases, the dust was so dense that their vision would be obstructed. This dust would also get into their lungs, which needless to say, was terrible for their health.7 These children sometimes even had a person prodding or kicking them into obedience to make sure their attention did not stray.

These working conditions for children continued until the United Kingdom’s Parliament passed the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842. The act included a report that informed the public about how children as young as five years old were working as trappers for “twelve hours a day and two pennies a day.”8 It was not until the Children’s Employment (Mines) Report came out alongside it in 1842 that Parliament passed the act that all boys and girls under the age of ten were not allowed to work in the coal mines.9 Even after this law prevented children under fourteen from working in the mines, people still found ways around it. For example, since some regions did not have a compulsory registration of birth, someone could easily lie and claim that these boys were simply “small for their age.” Finally, with this legislation came the snowball effect of humanitarians and a larger awareness of health and safety regulations for workers, which led to the start of the end of child labor in England.10

- Children’s Employment Commission First Report of the Commissioners (Mines), (Halifax: Irish University Press, 1842), 77-81. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica.com, December 2012, s.v. “Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th earl of Shaftesbury,” by Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. ↵

- New World Encyclopedia, February 2017, s.v., “Child Labor,” by New World Encyclopedia Contributors. ↵

- Great Britain Commissioners, The Condition and Treatment of the Children employed in the Mines and Colliers of the United Kingdom Carefully compiled from the appendix to the first report of the Commissioners With copious extracts from the evidence, and illustrative engravings, (London: 1842), 19-59. ↵

- J. M. Mason, “Protection of Children,” The Westminster Review Vol. 36 (1841): 66. ↵

- Jane Humphries, “Short stature among coal-mining children: A comment,” Economic History Review 1, no. 3 (1997): 533. ↵

- Jane Humphries, “Short stature among coal-mining children: A comment,” Economic History Review 1, no. 3 (1997): 535. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica.com, December 2012, s.v. “Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th earl of Shaftesbury,” by Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. ↵

- “Early Factory Legislation.” Parliament. UK. (April 9th, 2017). ↵

- J. M. Mason, “Protection of Children,” The Westminster Review Vol. 36 (1841); 45-47. ↵

98 comments

Roman Olivera

Wow, it’s crazy to think that children so small were being subject to such harsh environments for work. It isn’t that crazy to see children that small working as children of all ages had to work on most occasions in history, if it were farm work or other hard labor jobs, children of non-wealthy families were usually put to work. This was a line of work that you couldn’t get men to do willingly let alone women and children. I’m glad that people have advanced in their ways of thinking, to look out for the safety of our children. Education has became the new driving force we subject children to for 8-12 hour days including their homework, in a lot less toxic and harmful environment. Just kidding, I’m glad children are able to get an education a have a choice in deciding what they want to become and do for work when they get to the proper working age.

Marina Castro

The industrial revolution brought a lot of wealth and progress to England. However, with this came a lot of exploitation towards workers. Furthermore, a lot of this workers were children. It is very sad to know the conditions in which these kids had to live in. Today, child labor is heavily condemned because of how atrocious of an act it is.

William Ward

Placing children in such an environment is awful, and there are very few excuses that could justify that. With that being said, the bottom line is the kids were working and being paid so that they might afford food. In the twenty first century, most forms of child labor have been outlawed, so such terrible occurrences have been eliminated in most countries. Great article, very well written.

Honoka Sasahara

It was so hard for me to read about children of those times who were forced to experience such tough days. I wonder how terrible for them to think about endless days of exhaustive hardship.

Such tragedy is gone from England, however, there are many children who are made to work under awful conditions without going to schools. I hope their life comes to better as soon as possible.

Luisa Ortiz

I like the opening for this article it was like if i was placed in the little girls shoes. I used to work with Pre-K kids , and just thinking that my students and the boys and girls from this article are the same age is revolving my stomach. It’s hard to imagine that parents would risk their kid’s life, but then again they need to work in order to eat. I’m so happy that nowadays there is so many organizations that advocate for children life, but still feels like in many ways we are not over this time period. it has been one of my favorite articles to read, great images and use of similarities.

Constancia Tijerina

It is always so sad to hear about child labor and how even in todays world this still happens on the daily. Its so disturbing to read about this part of history and how these people could simply let these conditions slide. These children had no future as soon as they were sent to these coal mines. I enjoyed reading this article thanks to the extensive research that was taken place to get these children’s voices heard from what pain and horrible treatment they were out through. This was a great article overall.

Robert Rodriguez

This was so heartbreaking reading this, I can’t imagine working in a mine as a child.. in such cruel and horrible conditions. I think that even though there was a lot of jobs making 4 year olds work in mines is just plain wrong… im so glad we have labor laws in place now in both American and England to prevent things like this from ever happening again. The author did an amazing job on shining the light on these children that were put through horrific working conditions.

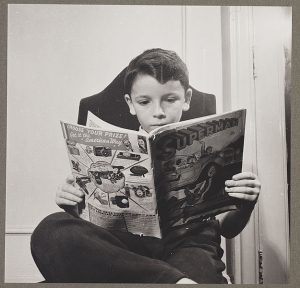

Anthony Robledo

The featured image is a powerful message all on its own! Combine it with this great informative article and you get something that you cant forget. It is horrible what these kids had to go through. Like come on. Working in the mines at 4 years old is just cruel. I just hope we never have to resort to that type of labor again. Great job on this article! Keep up the good work!

Fumei P.

A very interesting article discussing child labor in the 1700-1800s. Also, horrifying to think that children that were as young as four years old were working under such poor conditions. Life in the twenty first century, when I was playing with Barbie Dolls and going to school seems like a dream compared to sitting in the dark for 12 hours at a time.

Michael Thomas

I found this article interesting because of how it details child labor in the coal mines of England. Children worked in the mines to make money for their families. The conditions the children worked in were unsafe, dangerous, and bad for their health. If it was not for the regulations that prevented children from working in the mines, the children could have either have been killed in the unsafe environment or develop health problems.