The tranquil night in Satsuma was broken by the roar of an artillery barrage. Airburst shells hammered the side of Mount Shiroyama as 30,000 soldiers of the newly formed Imperial Japanese Army encircled the foot of the mountain, preparing for the attack that would begin in mere hours. From inside a cave, a man looked out to take measure of the battlefield. In the distance, he could see the faint glow of lanterns in Kagoshima, the city he once called home. Below, he could see the flash of the artillery that was pounding his army’s positions. It was clear that his army of samurai, which had been degraded to a mere 300 men, would soon be defeated. And so this man, Takamori Saigō, prepared for one last battle.1

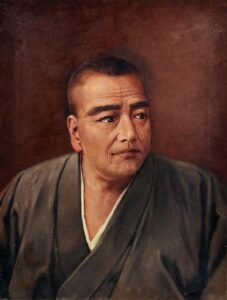

Less than ten years before, Saigō had been a restorationist leader, seeking to abolish the Tokugawa Shogunate that had ruled for over two centuries. He and many others felt that the shogunate’s submission to the unequal treaties was a sign of weakness and a betrayal to the people of Japan.2 So, many samurai sought to restore the emperor, who had merely served a ceremonial role despite officially being at the top of the Edo hierarchy, as the true ruler of Japan. This division between the restorationist and shogunate forces would culminate in the Boshin War in 1868, during which Saigō led a partially modernized force of samurai, laying the groundwork for what would become the Imperial Japanese Army.3 By the war’s end, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the last shogun of Japan, was defeated, and Emperor Meiji was restored to his rightful place on the throne. For his service, Saigō was granted a high position in the Meiji government, becoming one of the Three Great Nobles, who would have great control over the policies of the new government.

However, as Japan began its rapid transformation from a feudal backwater to a fully-fledged world power, Saigō increasingly found himself disappointed with the newly created government. While he wanted to modernize and reform the government and the country, he felt that the government was going about it the wrong way and incorporating all of the wrong things from the West. A particular point of contention was what was to become of the daimyo, the regional samurai lords appointed by the shogun, and their domains, a topic that Saigō frequently avoided discussing.4 In addition to that, he was frustrated by the government’s inaction against Korea, even after the king of the Joseon Dynasty refused to recognize Emperor Meiji’s legitimacy. His proposals for an invasion, one of which involved Saigō provoking his own assassination as a means to “justify” the attack, were repeatedly shot down.5 And so, in 1873, he would resign from the government. He returned to his home in Kagoshima, swearing off politics and wanting to retire from public life. Despite his withdrawal from government, though, the reforms continued, extending to the samurai. They had already lost their right to slay any commoner who disrespected them, and by 1876, they were also banned from wearing their daishō, the pair of swords that designated one as a samurai.6 These continued reforms on the caste system that had been in place for centuries had not gone unnoticed, especially by the samurai living in Saigō’s home of Satsuma on Kyushu Island.

Throughout all of this time, many samurai struggled and failed to navigate the seismic changes in Japanese society. Although some would go on to achieve great feats, many more would sink into poverty, as the pensions granted by the government proved to be inadequate, as many were used to receiving a stipend of rice as opposed to money.7 Employment was hard to come by, especially when many samurai were only good at fighting. But it was this skill, along with their anger over the loss of their privileges and way of life, that drove many disaffected samurai to rebel against the government. Many gathered in Satsuma, stockpiling weapons, ammunition, and other supplies while also taking note of the military installations there that were officially under imperial control.8 Upon hearing of this, the Meiji government grew both suspicious and worried, especially considering the other major samurai rebellions that had taken place within Kyushu in the past few years. So, in addition to a warship being sent to seize munitions in Kagoshima, a group of police spies from Tokyo led by Nakahara Hisao were sent to investigate the activities of the rogue samurai.

Neither mission went well. The samurai were able to save much of the munitions they had stockpiled before the navy could seize them, and Nakahara and his spies were captured. Under torture, he gave the dubious confession that they were part of a plot to assassinate Takamori Saigō. The extent to which this confession was true is still uncertain, but whether it was true or not, it was the spark that would light the keg.9 Once Saigō heard of this on top of the activities of the rebellious samurai, he decided to take matters into his own hands. Although he had never advocated for open rebellion, he felt compelled to take the reins of this movement as its leader. Luckily, Saigō had an ace up his sleeve. He had not spent his retirement idle; after he withdrew from the government, he had been running shigakkō, private academies that, along with foreign languages and Chinese literature, taught modern infantry and artillery tactics. Many disaffected samurai had enrolled in these schools, becoming loyal to Takamori Saigō himself.10 In total, Saigō was able to initially martial a sizable force of 12,900 samurai. Each man carried his swords, guns, and 100 rounds of ammunition, along with whatever other provisions they needed. Armed with these and a burning desire to defend their way of life, they set off to march on Tokyo to “ask questions” of the imperial government.11

Saigō identified the city of Kumamoto as his first objective. The castle there was a major stronghold garrisoned by imperial soldiers, and if it was not taken, then the garrison stationed there may attack his army’s exposed flank or even obstruct his march to Tokyo altogether.12 Initially, he had hoped that the people of Kumamoto as well as the soldiers in the garrison would be sympathetic to his cause, especially considering that many of the officers within the garrison were natives of Kagoshima. But this hope was quickly shot down as Major General Tani Tataki prepared to meet the approaching rebels with force. He was able to muster 3,800 soldiers, along with 600 Kumamoto police officers. Always a careful man, Tani began to take a defensive position; he wasn’t going to risk any defections that may occur in any offensive action. And thus, despite the overwhelming odds, the first battle of the war was about to begin.13

The flighting began on February 19, 1877. The imperial forces were severely outnumbered and by February 23, they were forced to retreat into Kumamoto Castle itself. The Satsuma rebels dug into defensive positions, laying the castle under siege. Although imperial forces within the castle held firm, things were becoming increasingly dire. Food and ammunition were rapidly declining, and their contact with outside help was firmly cut off.14 Not only that, but many other disaffected samurai, sympathetic to Saigō, would end up joining his army’s cause. Although these men would have little to nothing in common in terms of ideology, they would still aid in the goal of “asking questions of the government.” So, as the army struggled against the onslaught of samurai, the rebel forces only got stronger. But things were by no means easy for the rebels, either. They had severely underestimated the resolve and skill of the Imperial Army. Even as supplies were dwindling, they fiercely fought Satsuma forces, laying out landmines to slow down assaults and having sharpshooters in the upper parts of the castle prevent them from setting up their artillery. Nevertheless, the siege grew to a stalemate, as soldiers on both sides struggled through the rain and mud, trying anything they could to strike a decisive blow.15

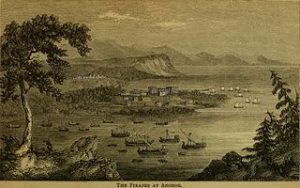

The government and military knew they had to act fast in order to suppress the rebels. Luckily for them, Saigō’s decision to bring all of his forces with him would end up backfiring, as his home city and base of Kagoshima was left practically defenseless. So, in early March, a large imperial force consisting of soldiers, marines, and policemen landed in Kagoshima almost unopposed. They were able to seize all remaining munitions and free Nakahara and the rest of his spies. The Satsuma governer, Ōyama Tsunayoshi, was taken into custody, being sent to Osaka for the rest of the war.16 With Kagoshima under imperial control, the rebels now had nowhere to return to, and the Satsuma Army was left practically adrift. Worse still, a large imperial force had been sent to relieve Kumamoto Castle and crush the rebellion. So, Saigō took a portion of his force north to intercept the imperial force. The two sides met at Tabaruzaka Hill on March 3, 1877. They fought for seventeen long days in some of the most brutal fighting of the war, with both sides racking up 4,000 casualties each. However, by March 20, Saigō was forced to retreat. They fled west to the town of Ueki, hoping to stall the imperial advance. Though they managed to slow them down, it merely delayed the inevitable as they were once again sent on the run by April 2, and on April 14, the rebels were driven out of Kawashiri as well. It was this defeat that led to Saigō abandoning the siege of Kumamoto Castle, allowing it to fall back into imperial hands after 55 days of fighting. The Satsuma Army fell back to their camp at Hitoyoshi in mid-April but was quickly forced to abandon it after three grueling weeks of combat with the imperial army. Any hope of reaching Tokyo was now snuffed out as Saigō was forced into constant state retreat. What had begun as an organized uprising quickly devolved into a fight for survival as the remainder of his force fought desperately to make their way home to Kagoshima.17

With ammunition low and much of their artillery having to be abandoned for the sake of greater mobility, Saigō’s forces were forced to turn to guerrilla warfare whenever combat was inevitable. In an attempt to keep ahead of the army, he split his force into two. His core force was to head south to Miyakonojō from Hitoyoshi, while Saigō would head east to Miyazaki. However, the imperial army was in pursuit of the main force, successfully defeating them on July 24 before heading to Miyazaki. Saigō’s forces fled northward to Nobeoka, where they met imperial forces on August 10. Many expected this to be the end—the rebels were outnumbered by at least 6 to 1, and were completely encircled by the imperial army. And yet, miraculously, they managed to slip away by August 18, continuing their retreat towards Kagoshima.18 But these battles had been costly for the Satsuma Army. By the time they were in sight of the city in September, they had been reduced to a mere 500 men. With the imperial army still in pursuit, Saigō took up a defensive position on Mount Shiroyama as imperial soldiers encircled him below. They had been constructing defenses, ensuring that there was no possible means of escape for the rebels. On September 23, Yamagata Aritomo, commander of the imperial soldiers, sent one last letter to Saigō, offering him one last chance to surrender. Saigō sent no reply—he wasn’t about to betray the way of the samurai. So, on that night as imperial soldiers bombarded the Satsuma positions, Saigō and the last few hundred samurai made their final preparations. It was clear that they were going to die—but they would die with honor.19

On the early morning of September 24, the final battle began. Ammunition was so depleted that the samurai were forced to use nothing but their katanas. Still, they fought valiantly despite the overwhelming firepower that they were facing. But early on in the chaotic fighting, Saigō was hit—a stray bullet had shattered his femur, and he was unable to fight on. So, being too horrifically wounded to commit seppuku himself, his friend, Beppu Shinsuke raised his katana and with a single swing, beheaded Saigō. Beppu then turned to rejoin the battle. By 6:00 AM, the several hundred samurai had been reduced to just forty. With nowhere else to go and nothing else to do the last of the samurai charged the imperial soldiers. And it was there, amidst the crackling of rifles and the fog of smoke and gunpowder that the samurai, a class that had existed for over six-hundred years, came to a bloody end. And for all their losses, only thirty imperial soldiers were killed.20

This final battle solidified Japan’s political transformation. With the Satsuma Rebellion’s end, the last remnants of the feudal way of life were gone, and Japan devoted itself fully to its future—one of industrialization, technological advancement, and of course, strong militarization. Although Takamori Saigō spent the last few months of his life as a rebel, he was and still is fondly remembered as a hero—a noble samurai—fighting to the very end for the way of life that had existed for more than two hundred years. Emperor Meiji would even posthumously pardon Saigō, holding him as an example of martial valor. This idea of sacrifice, loyalty, and bravery would help to popularize the idea of bushidō, the moral code that would guide the new warriors of Japan—the soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army. As feelings of nationalism began to sweep the country, they would come to see themselves as modern samurai, ready to serve the emperor until their very deaths. To the Japanese people, Saigō’s last stand was an act of heroism, one that they should strive to live up to, and as Japan turned its attention to its primary colonial ambitions of Korea and China, they were more than eager to do so. For better or for worse, this new idea was here to stay, and it would guide the Empire of Japan’s foreign policy.21

- James H. Buck, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877: From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle (Tokyo, Japan: Sophia University, 1973), 446. ↵

- Charles L Yates, Saigō Takamori in the Emergence of Meiji Japan (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 458. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 2004), 153-155. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 2004), 168-169. ↵

- Marlene J. Mayo, The Korean Crisis of 1873 and Early Meiji Foreign Policy (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1972) 811-812. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 2004), 198. ↵

- Harry D. Harootunian, The Progress of Japan and the Samurai Class, 1868-1882 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1959), 263. ↵

- James H. Buck, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle (Tokyo, Japan: Sophia University, 1973), 429. ↵

- James H. Buck, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle (Tokyo, Japan: Sophia University, 1973), 429-430. ↵

- James H. Buck, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle (Tokyo, Japan: Sophia University, 1973), 428. ↵

- James H. Buck, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877: From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle (Tokyo, Japan: Sophia University, 1973), 430-431. ↵

- James H. Buck, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877: From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle (Tokyo, Japan: Sophia University, 1973), 432. ↵

- James H. Buck, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877: From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle (Tokyo, Japan: Sophia University, 1973), 436. ↵

- James H. Buck, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle (Tokyo, Japan: Sophia University, 1973), 443. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 204-205. ↵

- James H. Buck, The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. From Kagoshima Through the Siege of Kumamoto Castle (Tokyo, Japan: Sophia University, 1973), 441. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 207-208. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 208-209. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 210. ↵

- Mark Ravina, The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2003), 5. ↵

- Mark J. Ravina, The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigō Takamori: Samurai, Seppuku, and the Politics of Legend. (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 701-703. ↵

2 comments

Mariana Chamorro

Hey Nikko, your piece on the Satsuma Rebellion is awesome! The way you tell the story really pulls you in, making it feel like you’re right there witnessing the action unfold. Your passion for the subject shines through, and it’s clear you put a lot of heart into it. Keep up the fantastic work!

Eduardo Saucedo Moreno

Hello Nikko!

I really liked your article! I have never done research on Takamori Saigō but this piece definitely helped me be more educated on the Japanese history. I would’ve loved to see maybe like 2 more images that can fully grasp what each paragraph is talking about. Other than that, I love learning about history so this was definitely a fun read!