Democracy. A word we’ve heard all of our lives- a way to describe the country we live in, a way to describe the type of government we have, an ideal that we have parroted from our teachers or parents. Democracy has become such a familiar word with no concrete base, a word used so often its lost meaning in the practicality of implementation.

“After Babel” by Jonathan Haidt analyzes the recent erosion in democracy and what we face in today’s climate. Through identifying trust as the main factor in facilitating conversation between groups, he underlines the degradation of the virtue. Without being able to trust each other, we’re not able to properly function in the system of democracy we have in place. One of the main factors in this erosion of trust is the widespread introduction of social media, and the unintended consequences it has had over the past decade. These open and unmoderated platforms encourage users to advocate for views their group of friends supports by effectively serving as a stage, letting users make statements and subjecting them to the praise or shaming of that idea. However unlike a stage, social media is entirely done at a distance, and because of this it creates a disconnect between the actions of one who is disagreeing and the person on the other end. As a result of this, groupthink has become increasingly present not just online but in everyday life, as more adults have grown up with internet access having shaped their personality. This has dire implications for the core idea of democracy, as the internet echo chamber has fostered a culture that shuns the ideals of civility and cooperation between people with different views 1.

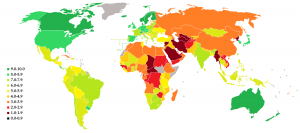

There is a global concern in the understanding and practice of democracy. The lack of concreteness in perpetuating democracy has been felt across nations. Organizations such as the United Nations (UN) and the Organization of American States (OAS) actively work towards strengthening the democracy of their individual nations as well as regionally. Democracy, ruling by the people, is seen as the most representative, inclusive form of government intent on creating transparency and fairness 2. According to Freedom House, a reputable organization that seeks to create a nonpartisan research base discussing democracy, democracy is withering. Long-term democratic decline was exhibited internationally as last year 75% of the world’s population faced democratic deterioration in their country. However, countries like Russia and China are only continuing to develop and amass international power, according to Freedom House 3. In light of the circumstances, it is necessary to expand on the discussion of furthering democracy in a way that is sustainable and effective.

In “The Struggle for “Thick” or Transformative Citizenship and Democracy in Australia: What Future Teachers Believe and Why it is Important”, the author, David Zyngier, invites teachers in Australia to discuss the foundational relationship between democracy and education. Australia’s governmental system is similar to the United States as they are based in elected representation. Through investigation, Zyngier described that although the teachers related democracy to voting and education, many could not describe what democracy looks like in other countries. Zyngier pointed to the vagueness of many of their answers as a “thin” (hollow) understanding of democracy 4.

However, one of the respondents relayed that, “Democracy is intended to provide equality for all citizens of a country. Formal equality in terms of access to public systems of: health, education, employment etc. Informal equality in terms of social systems, within the “community””. This “thicker” account of democracy highlights the connection between education and democracy 5. Similarly, Kathy Hytten, a professor of the philosophy of education, elucidates that “there is an integral and reciprocal relationship between democracy and education” in her paper “Democracy and Education in the United States”. Hytten pulls on the interconnectedness of rights and obligations to each other, reminiscent of Simone Weil’s “On Rights and Obligations”. Both describe the obligation of both the individual and community to respect the rights of others. Weil hammers in the point that obligation to another exists outside of whether society recognizes it or not, contrastingly, rights exist only through the acknowledgment of society. Building off of this idea, Hytten describes education as an obligation we owe to other individuals, making the claim that education is necessary for a society in which we expect the recognition of individual rights 6.

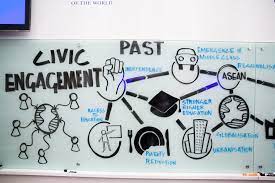

One of Hytten’s main arguments is that the democratic schooling approach is the best way to achieve a society that recognizes both the rights and obligations of an individual. The democratic schooling approach is often referred to as a civic engagement curriculum “including how to access information, determine the veracity of claims, think critically, research problems, ask questions, collaborate with others, communicate ideas, and act to improve the world” 7. Hytten believes that to further democracy, nations need to invest in their education systems and develop civic engagement curriculum to encourage students to think critically and participate in activism.

While the idea that culture and environment informs the actions of society and vice versa is generally well established, Hytten’s perspective is strengthened by Dr. Muneera Alshurman’s response. In her article “Democratic Education and Administration” she discusses the importance of highlighting the relationship of democracy in education. Citing that, “The best way to educate people about democracy is to incorporate democratic education and administration in schools,” Alshurman argues for the fortification of democracy through Model Nations and civic engagement curriculum 8. Through arguing for Model Nations and civic engagement curriculum she robustly advocates for a deeper understanding of democracy through learning-by-doing.

Civic engagement curriculum is designed to offer a means for students to grow in their understanding of their civic responsibility. Civic engagement curriculum focuses on developing the ability to resolve conflict on a larger scale. These courses include discussions of society, systems, race, and many more challenging topics. Similarly, Model Nations is a type of educational simulation that allows students to research and represent a type of government. Model Nations allows students to organize and problem-solve in the democratic spirit.

One of the unique aspects of Model Nations is the language used during conferences. In Model Organization of American States, or OAS, parliamentary procedure serves as the backbone of democratic communication. In Model Nations each participant is a part of a country’s delegation and charged with furthering the agenda of their country through democratic diplomacy. Model UN has over 200 chapters and 200,000 members in the United States. This expansive network of people is made up of students who have the desire to learn about democracy and the democratic practices of nations. Model UN supports the development of values and empowerment in their participants. Model Nations curriculum is based on the sustainable development goals of the UN and the principles of democracy. Focusing on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, provides a comprehensive list of goals to work towards through democracy. Each nation must respect the sovereignty of other nations, but they must work, democratically, together to achieve these important objectives. Because each nation is represented, Model Nations provides the opportunity to model different types of governing bodies and create an international context.

The language used within the educational simulation includes no personal pronouns. The individual must use “the delegation of …” in order to address themselves, similarly when referring to another individual they would use “the delegation of (the other’s country)”. This allows the participants to remove themselves and their feelings from the discussion. By making the nouns impersonal, the participant speaks not just for themselves, but their country. This creates a barrier between personal opinion and the opinion of the state. The language used defines the responsibility of the individual to maintain their country’s perspective.

In a related manner, in order to preserve order and decorum every action proposed by a delegation (motion) must be made through the chair (the moderating third party) and approved by the chair. These motions include a motion to ask another delegation a question, to speak, and to propose other actions such as voting. By requiring delegations to pose motions through the chair this creates another barrier between different country’s delegations. The language creates a respectful environment to give each participant’s delegation the opportunity to embody the country while respecting other’s obligation to embody theirs.

Through the language the delegations relies on Model OAS preserves democracy and helps to further students understanding of its importance. Through the encouragement of students from educators to participate in civic engagement curriculum and Model Nations, there is a remarkable opportunity to deeply educate students in democracy. Helping students understand civic engagement will help future generations also better understand and filter through the growing number of social media posts they are bound to encounter.

- Jonathan Hadit, After Babel (The Atlantic, 2022) ↵

- Anup Shah, Democracy (Global Issues, 2012) ↵

- Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz, Democracy under Siege (Freedom House, 2021) ↵

- David Zyngier, The Struggle for “Thick” or Transformative Citizenship and Democracy in Australia: What Future Teachers Believe and Why it is Important (Research Gate, 2013) ↵

- David Zyngier, The Struggle for “Thick” or Transformative Citizenship and Democracy in Australia: What Future Teachers Believe and Why it is Important (Research Gate, 2013) ↵

- Kathy Hytten, Democracy and Education in the United States (Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, 2017) ↵

- Kathy Hytten, Democracy and Education in the United States (Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, 2017) ↵

- Muneera Alshurman, Democratic Education and Administration (Science Direct, 2015) ↵

10 comments

Lionel Mbati

Congratulations on your nomination, Sophia! This was a well-researched and well-written article. I like the approach of incorporating democratic education and administration in schools as described by Kathy Hytten. This in addition to Civic Engagement which is often interactive would allow individuals to have a larger perspective other than that promoted within their echo chambers. This would in turn contribute to actual dialogue in open forums and each side arriving at concessions in helping solve some of the problems we face today.

Our democracy is undergoing a serious test, but despite the fears, occasional bad actors, and a need for more civic engagement. I am confident that it will stand.

Sarah Guerrero

Sophia, congratulations on this wonderful publication. As a strong believer in education and bringing in a greater transparency to politics and diplomacy. This was a great article and I would love to hear more about your plans to implement this earlier than post-secondary education. Best of luck!

Dejah Garcia

Great article congratulations on your nomination ! This article does a great job of explains the civic engagement and help me see a different perspective of our adults in society towards the democracy system. Overall, you did a great Job the article was organized and you diction was on point. Again congratulations:)

Helena Griffith

Salut, Sophia! Congratulations on winning a nomination, first and foremost! Understanding is, in my opinion, crucial to civic engagement. The author of this post does a fantastic job of elaborating on that. Don’t stop working! I appreciate how this was highly educational and helped to further enlighten me.

Kayla Braxton-Young

This was an interesting article. It made me think of a lot of tiny things that many nations do to improve their educational systems. The disparities in education, including early schooling with their youngest residents, can foretell the future happiness, stability, and economy of the nation. I’m trying to recall which nation encourages kids to pursue their passions in education rather than adhering to a rigid curriculum. They urge their pupils to participate in community activities and to have discussions and experiences about civic involvement.

Ana Barrientos

Congratulations on your nomination! I loved how detailed you were, and your article is well researched. I also enjoyed how you talked about different ways for people to get educated. I think it is important to talk about Democracy and educate people about it. Voting is such an important part of a Democracy, and everyone should be taught about it. Overall, awesome job!

Grace Ibarra

Hi Sophia! Congratulations on your nomination! I think you topic is so important and informing the community about civic engagement is so essential. Voting is an immense power and can create change if and when voters are informed.

Victorianna Mejia

Congratulations on your second publication and your nomination! Reading your article reminded me of many little things different countries do with their education system. The differences in education can predict the future of the country’s happiness, stability, and economy, including early education with their youngest citizens. I am trying to remember which country encourages students to study what interests them most instead of having a set standard of what is needed to be taught. They encourage their students to be involved with the community and have civic engagement conversations and experiences. I believe that country landed with one of the best education, healthcare, and economies in the world.

Vanessa Preciado

Hello Sophia! First off congratulations on winning a nominee! I think understanding in civic engagement is very pertinent. This article does a good job on explaining just that. Keep up the work! I like how this was very informative and enlightened me a bit more. Thank you for the read!

Kelly Guadalupe Arevalo

Hello Sophia. Great article! I wish my school had included some of these activities. It is really important that the students understand the power and responsibilities that they will have as adults in society, and learn about the way democracy works in different countries. I think that your idea, along with leadership initiatives, would change the educational system for the better. Good job!