Introduction To The Sustainable Wood Market

It makes our furniture, it’s the paper we write and draw on, it holds up our houses and burns in our fireplace – wood is an unavoidable and crucial part of our day-to-day lives. Presumably, everyone is familiar with the importance of wood and its various uses, but did you know it can get specific certification labels, the same way organic food at a grocery store does? Just like a bag of carrots can get an ‘organic’ or ‘sustainably grown’ tag, the wood we use can get stamped with a label signifying that the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) found the forest from which the wood was sourced to be appropriately managed for logging and consumption. One may read this and be confused on what the FSC is, and why their label matters.

It is understandable that most readers may be unfamiliar with wood supply; the inner workings of logging and forestry aren’t as widely publicized and popular as the wood products we use. Wood as a resource is something that humans do not want to run out of, and although not a forethought like food or water, it is used everyday and must be kept in global supply. Certified goods hold a higher degree of respect or value in any kind of market, and whether it be meat, produce, or clothing, consumers feel better buying products that are labeled free range, organic, or ethically produced.1

If a farm is certified organic, the food it produces gets to boast an organic sticker label. The same is true for a chair made of wood that comes from a FSC certified forest. FSC-certification of wood products can serve as a marketing point that benefits a company’s image, while keeping important forests secure and supporting an industry that strives for sustainability.

What Is The FSC and What Do They Do?

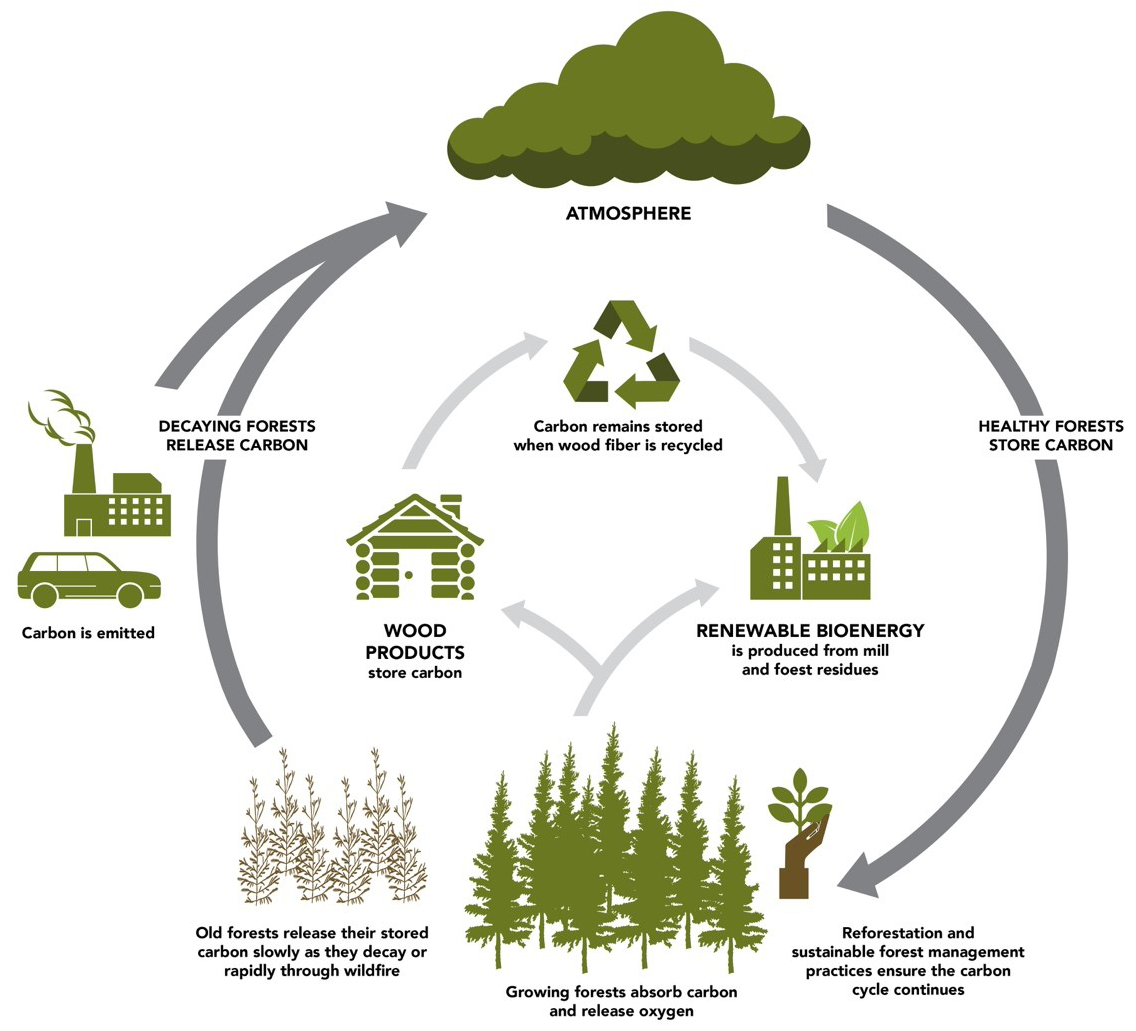

As industries become more aware of humanity’s environmental impact, they have focused more towards keeping practices sustainable. A more sustainable model can’t include merciless chopping and hacking through forests for more wood; more is required than just the lumber in those ecosystems. This is where the FSC comes into play. The primary goal of the FSC is to make the global wood market not only more sustainable for the sake of the environment, but to keep it and any products it produces economical, socially sound, and beneficial. The first big step in managing forests is to conserve them, and consider all the ways they contribute. The official FSC mission statement is: “FSC will promote environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable management of the world’s forests.”2

The FSC is one of two primary forest certification organizations. Controlling the global wood supply is a large part in forest management due to lumber and trees being such an important natural resource to both humans and wildlife. The standards of the FSC are structured around a set of 10 principles and 70 criteria. Forests that are compliant have their wood labeled as ‘FSC-Approved’. Lumber cut from FSC-certified forests is then stamped with the organization’s logo to ensure its certification up until processing (Figure 1). Since wood is not required to be FSC-certified to be harvested, mixing of raw lumber from various, non-FSC certified sources once they are sold off for processing is inevitable. The authors of “Stakeholder Engagement in a Forest Stewardship Council Controlled Wood Assessment” explain that, to avoid a dishonest mix that discourages their messaging and goals, the FSC has developed a separate set of standards for what wood is allowed to be mixed with their 100% approval labeled woods. These rules are called the FSC-Controlled Wood standards. The wood is not certified through audits like the wood with an FSC-certification label but are, at the very least, strictly controlled to avoid illegally- or unethically-sourced woods.3 To meet these standards, a forest management enterprise/company is required to prove that their non-FSC certified wood is sourced in a controlled manner. One type of this controlled production is achieved is through identifying and avoiding the use of High Conservation Value Forests (HCVF). High Conservation Value Forests are defined by the FSC as forests that carry any sort of special biological, ecological, social or cultural values, and are primarily what the FSC strives to protect and manage.4

What exactly are the qualifications for a forest to be an HCVF? There is no one standard, but determining the conservation value of a forest often includes the context of its location. This could include the forest’s place in the surrounding society, the species it contains, or the ecosystem services that it provides. Ecosystem services and species diversity are often looked at first when valuing a forest. If a forest has a large array of highly valued, unique, or endangered species, its conservation value goes up. Classifying a forest as an HCVF aids in the preservation of biodiversity. If a forest provides a large amount of ecosystem services, specifically those that directly benefit human populations, then that also factors into determining its conservation value. Ecosystem services can be defined as nearly any resource or system that provides people with something of importance. An ecosystem service can range from something as simple as raw materials, or to something as complex as a spiritual or historic site. Species diversity in itself can be considered an ecosystem service, as ecological variety gives options and balance to a food web and stability to the niches we and other species rely on. The way a stream provides fish and clean water is just as important of an ecosystem service as the land being a sacred place of worship to native communities.

Forest Stakeholders

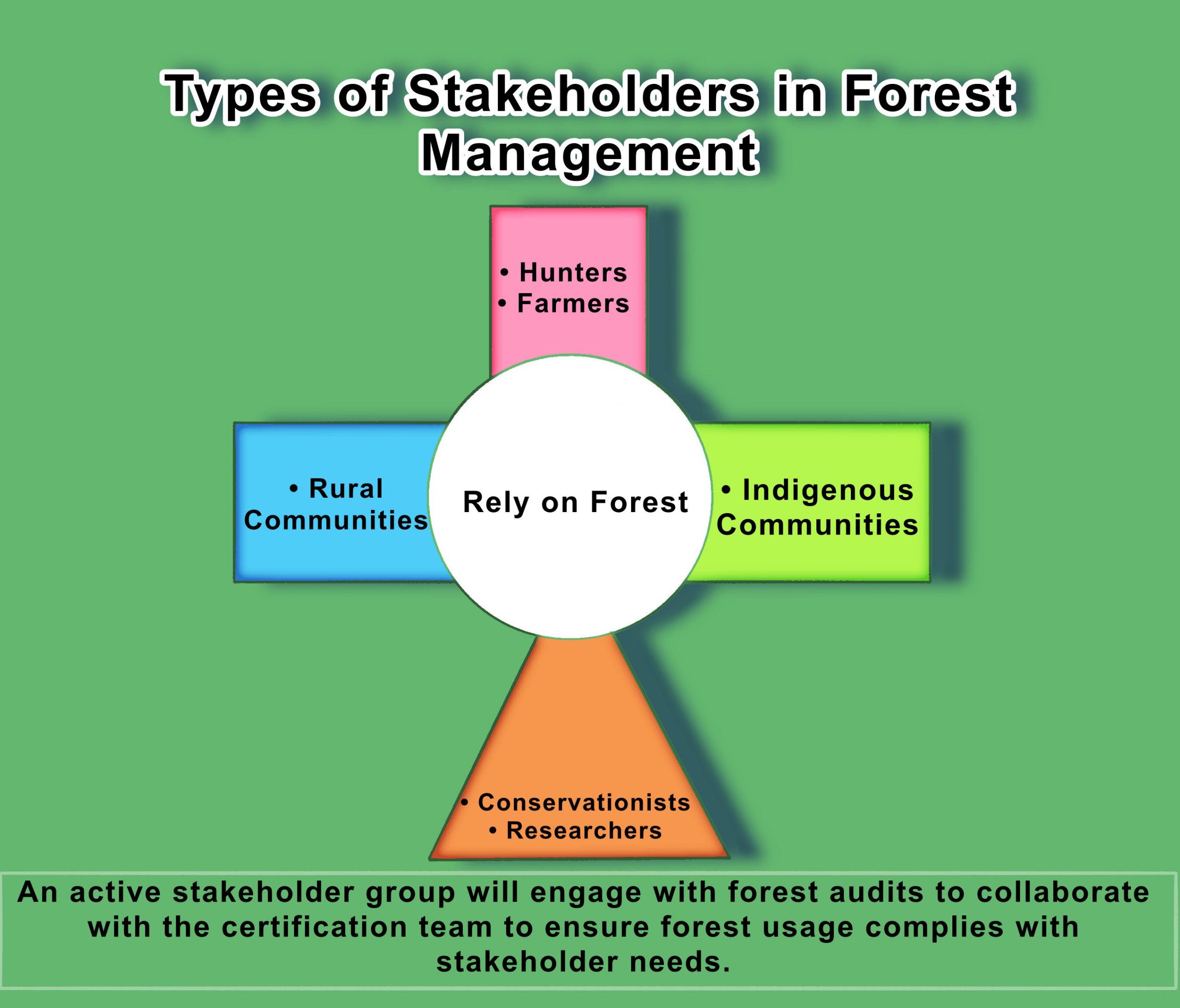

Anything the forest ecosystem provides is potentially a service to those utilizing it, and these ecosystem services become increasingly important in determining who stakeholders are for certain forests. If you find yourself relying on a forest for sustenance, spirituality, conservation, research, or even just recreation, then you just might be a stakeholder in that forest.6

Stakeholders for a forest are broad in definition. While it is true that people can own the forest land, not every stakeholder has a role as a property owner (Figure 2). A stakeholder could be a hunter, an indigenous community, a botanist that frequents the forest for research, conservationists, or even just a family that often camps there. If one is utilizing the forest, needs it for daily life, or in general cares about its maintenance, they can be a stakeholder. Not every stakeholder actively participates in forest management, but its always an option, and it is important for possible stakeholders to be consulted in decisions involving the health of a forest. Stakeholders play an important role in the fate of many forests, and any logging should not only include consultation and approvals by officials and land owners, but also those directly and indirectly impacted by altering the forest. The ‘stakes’ are not only within the hands of a logging company, wood consumer, or the FSC, but also the regular people that use the forest.7

Native communities are very important stakeholders in forests worldwide. Many indigenous reservations already have so little in the way of government resources or funds that they resort to traditional hunting gathering and agriculture to make ends meet. Often this is not only done out of respect for tradition, but to sustain their community. The same can be said for water sources within forests, as many native communities, especially in the United States and Canada, lack proper plumbing or clean water and rely on delivered water or the off chance of fresh surface water.8

Because of their dependency and frequent spiritual and cultural connections and usages with forests near their communities, indigenous people are often very reliable stakeholders in forest evaluations and stewardship. Many forests overlap or reside entirely within designated national parks; for example in New Zealand, the Tūhoe, part of the indigenous Māori people, live in the vicinity of the Te Urewera National Parkated. The Tūhoe are now engaging as active stakeholders to benefit and improve the land’s management and maintenance.9

FSC Wood Audits

The way the the FSC is supposed to engage with their forest stakeholders in stewardship primarily revolves around allowing participation in the wood auditing process, or at the very least prior notification of an audit. Engaging with forest stakeholders not only allows for more sustainability, but a smoother interaction between the FSC, the certification body (usually a logging or forest company), and those within the immediate consumption and vicinity of the forest. The stakeholder groups almost act as a middle man between the FSC and audited body, so no fraudulent logging and labeling occurs. If an audit is successfully passed and approved, then that means the wood is suitable for FSC-certification. An FSC approval implies that under no circumstances was the wood categorized as coming from an HCVF, and that the regional HCVF standards do not include the wood that has been approved.10

This also implies that the certification body was approved by any stakeholders as well (Figure 3). The issue at hand is that this stakeholder approval doesn’t always happen. Since the certification body isn’t actually part of the FSC, they may not be in agreement with the logging constraints the FSC has in place. Though it is expected that the certification process includes reaching out for feedback from stakeholders, it is also easy to just leave them out of the picture. Without stakeholder engagement, inconsistencies with the regional HCVF criteria slip through the cracks, and an audit sprinkled with inaccuracies may be provided to the FSC. This results in parts of HCVF ending up logged with an FSC label, unknown even to the FSC.11

Examples like these are starting to be investigated and reported, exposing the exclusion of forest stakeholders that should be involved in forest stewardship. A recent case study was conducted on the Australian government-owned logging company, Vicforests, and their contribution to the exclusion of stakeholders through findings of fraudulent logging. By creating a model of the logged terrain, it was found that over a span of 15 years, 75% of the harvested forest plots were overstepping the slope bounds that met the HCVF constraints, in non-compliance with state regulations. These slopes were identified as parts of the forest important to water drainage, therefore granting them HCVF protection. Despite this protective designation, the certification body from VicForests stated that logging was permitted on the slopes under an unidentified regulation manual attributed to SCS Global services, and included stakeholder engagement. This major contradiction was not in line with FSC requirements, meaning the certification body was not following the FSC process correctly, misusing and possibly fabricating the reference guideline sources. to have slip by there must have been very little stakeholder interaction during audits, and that is exactly what was found. By posing as stakeholders and inquiring about audits, the authors found how little stakeholder involvement is in VicForests’ wood audits, thus giving an explanation as to why it took so long to notice the slope bounds being overstepped.12 A similar issue was reported through a study conducted by World Wildlife Fund (WWF)-Ukraine, where their findings concluded that roughly two-thirds of the stakeholders surveyed in Ukraine were neither involved nor even aware of FSC certification.13

To have active stakeholders means that the complete certification process from start to finish is as thorough as possible. Both positive and negative outcomes can come out of a variety of interactions concerning a forest that is utilized in many ways. A multifaceted set of views and opinions requires logging companies to take different perspectives into consideration in managing forest resources.14

- Hermina Drah. 2021. “24 Organic Food Statistics & Facts for a Much Healthier 2021.” MedAlertHelp.Org (blog). April 29, 2021. https://medalerthelp.org/blog/organic-food-statistics/.1. ↵

- Forest Stewardship Council. n.d. “Governance & Strategy.” Forest Stewardship Council. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://fsc.org/en/governance-strategy.1. ↵

- Taylor, Chris, and David B. Lindenmayer. 2021. “Stakeholder Engagement in a Forest Stewardship Council Controlled Wood Assessment.” Environmental Science & Policy 120 (June): 204–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.03.014.4. ↵

- Frewin Chambers. 2019. “2019-HCV-National-Interpretation-Guide.Pdf.” November 2019. https://hcvnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2019-HCV-National-Interpretation-Guide.pdf.2. ↵

- Forest Stewardship Council. 2020. “FSC – Mark of Responsible Forestry.” 2020. https://www.scsglobalservices.com/fsc-mark-of-responsible-forestry.1. ↵

- Frewin Chambers. 2019. “2019-HCV-National-Interpretation-Guide.Pdf.” November 2019. https://hcvnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2019-HCV-National-Interpretation-Guide.pdf.2. ↵

- American Forest Foundation. 2020. “Who We Are | American Forest Foundation.” 2020. https://www.forestfoundation.org/who-we-are/.1. ↵

- Lugo-Morin, Diosey Ramon. 2020. “Indigenous Communities and Their Food Systems: A Contribution to the Current Debate.” Journal of Ethnic Foods 7 (1): 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-019-0043-1.1. ↵

- Bataille, C.Y., K. Luke, T. Kruger, S. Malinen, R.B. Allen, A.L Whitehead, and P.O.’B. Lyver. 2020. “Stakeholder Values Inform Indigenous Peoples’ Governance and Management of a Former National Park in New Zealand.” Human Ecology 48 (4): 439–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-020-00170-4.1. ↵

- Forest Stewardship Council. n.d. “Governance & Strategy.” Forest Stewardship Council. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://fsc.org/en/governance-strategy.1. ↵

- WWF. n.d. “Sustainable Forest Management.” WWF Russia. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://wwf.ru/en/what-we-do/forests/.1. ↵

- Taylor, Chris, and David B. Lindenmayer. 2021. “Stakeholder Engagement in a Forest Stewardship Council Controlled Wood Assessment.” Environmental Science & Policy 120 (June): 204–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.03.014.3. ↵

- Kuras, Tetiana. 2020. “Majority of Stakeholders Are Not Involved in the FSC Certification, Says WWF-Ukraine.” June 19, 2020. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?364053/FSC-Ukraine.2. ↵

- Jakobsson, Rikard, Erika Olofsson, and Bianca Ambrose-Oji. 2021. “Stakeholder Perceptions, Management and Impacts of Forestry Conflicts in Southern Sweden.” Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 36 (1): 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2020.1854341.3. ↵

- WWF Russia. 2019. “First FSC-Certified Forest in the Russian Caucasus Paves Way for Sustainable Forest Management.” November 2019. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?356334/First-FSC-certified-forest-in-the-Russian-Caucasus-paves-way-for-sustainable-forest-management.1. ↵

- “Sustainable Growth: Ontario’s Forest Sector Strategy.” 2019. Ontario.Ca. 2019. http://www.ontario.ca/page/sustainable-growth-ontarios-forest-sector-strategy.3. ↵

4 comments

Andrew Ponce

The author initially chose a topic that is very interesting to audience members in this current generation. The article goes into details with the process of how these companies achieve success with many people finding it sad. Much of the article focused on FSC and how wood is legalized and graded. Overall, the article is extremely informative and interesting to read for students of this generation.

Carlos Hinojosa

That’s actually very interesting way of going at it to save forests. Involve the concept of you losing your money and everyone would be environmentalist. It’s a shame they have to use that tactic to even have any sort of success but that’s the world these days. Honestly if the government was just stricter on people and companies then saving the environment would be child’s play but it’s already far too gone for that to happen. Very well-made article and i hope to read more.

Velma Castellanos

I was hooked as soon as I read ‘forest’ in your title because I am a big nature lover. I love how you started your introduction and it was clear. The way you explained what certain words meant was very informative. I enjoyed it because I did not what a lot of certain words meant until you explained it. I also noticed your long list of credits which makes me know that you are a scholar.

Luis Molina Lucio

This article is very well written as it takes on a topic and is very clear with the points made. I appreciate how there were two key points which were FSC and how stake holders are crucial to forest sustainability. This article not only informs but conveys a feeling right from wrong, although a very informative article it also expresses a need to hold people including oneself for how forests are used. The FSC topic took a very important chunk of the article because it was what determines how wood is graded, and where it comes from along with it also being obtained legitimately. (Learned what FSC was, have seen it but never really read about it.) More so, at the end this article also not only asks but responds clearly to why stake holders are the key to forest sustainability.