“Excepting South Carolina alone, Texas had more to do with starting that colossal blunder and crime than any half dozen other states of the Confederacy, and that without the movements of Texas, the Rebellion would have aborted in its earliest stages, and closed as ridiculous farce, instead of in that horrific tragedy.”– Charles Anderson.1

San Antonio, Texas is a city most known for the Battle of the Alamo, as well as for its Tex-Mex culture, which is apparent throughout the city since its foundation. However, many do not know of a second battle at the Alamo that happened during the American Civil War. The American Civil War, which ran from 1861 to 1865, was a horrendous time in American history in which brother was fighting brother and many families were divided between supporting the Unionists or the Confederacy. Americans were forced to choose a side and many did for various reasons. Many Unionists were either anti-slavery or pro-preservation of the nation, or both. On the opposite hand, many Confederates were pro-slavery, pro-states rights, or both. San Antonio, as a prominent military headquarters and the largest Texan city at the time, was therefore an important city for secessionists to take hold of. In the eyes of Charles Anderson, Texas was at the heart of the Confederacy’s chance at success, and San Antonio was at the center of it all. There were, however, many Unionists in San Antonio that advocated for the state to remain in the Union, but these cries of loyalty would not reach their representatives who, on January 28, 1861, voted to secede from the Union. Charles Anderson and his family were one such Unionist supporter caught in the midst of the Civil War. Anderson’s fight to preserve the nation and fight alongside the Union led to one brilliant story that showcases the conditions of those who favored the preservation of the Union in San Antonio during the Civil War.2

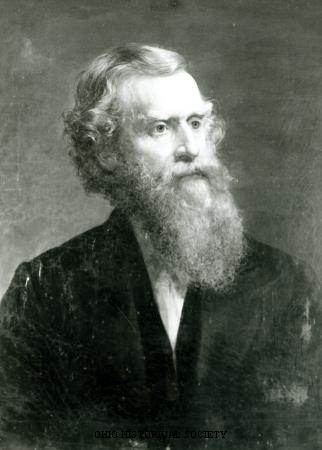

Charles Anderson was born June 1, 1814, the son of Richard Clough Anderson who fought in the American Revolutionary War, and brother to his twelve other siblings.3 As a Kentuckian native, Anderson moved and graduated from law school from Miami University in Dayton, Ohio in 1833. He practiced law for a while in Ohio, and even became superintendent for a local school. Known for his dedication to public education, riding the city on horseback to count all children in the area, he quickly became beloved by those in town. That led him to run and win an Ohio Senate seat, where he served his community as a Whig and was a known advocate for African Americans.4 He was known for advocating that African Americans should have the right to testify in legal trials. He was anti-slavery; his stance landed him much praise and criticism from other senators.5 Draves describes, “No one knew of the evil of slavery better than he did.” Anderson had grown up in Kentucky in a family that owned slaves.6 Despite his growing career and reputation in Ohio, and after traveling throughout Europe for several months, Anderson along with his wife, two daughters, and one son, decided to move to San Antonio, Texas in 1859, for health reasons.7 Anderson, severely asthmatic, found comfort in the clean, dry air of San Antonio, Texas. With Ohio behind him and San Antonio in front of him, Anderson could not have known the journey he would endure because of the Civil War that was only beginning to ramp up in San Antonio.8

San Antonio was a bustling, lively city during the 1860s that had not long ago fought in the Texan Revolution and then in the Mexican-American War in the 1840s. The city was home to an array of people such as white, slave-owning Southerners, Mexican immigrants, and German immigrants.9 In 1860, only one year before Texas officially seceded from the Union, Wallace describes that “[San Antonio] had a population of only 8,235 persons, it was, nevertheless, the largest city in the state of Texas.”10 In addition to this was the slave population of 592 African Americans—267 men and 325 women.11 Commerce Street, Market Street, and Alameda Street were the center of business and commercial industry that cultivated the Casino Club and brought a blend of social and business life to San Antonians. Aside from its flourishing community, San Antonio was the military headquarters of the Department of Texas and played an important political role in Bexar County, and in Texas as a whole.12

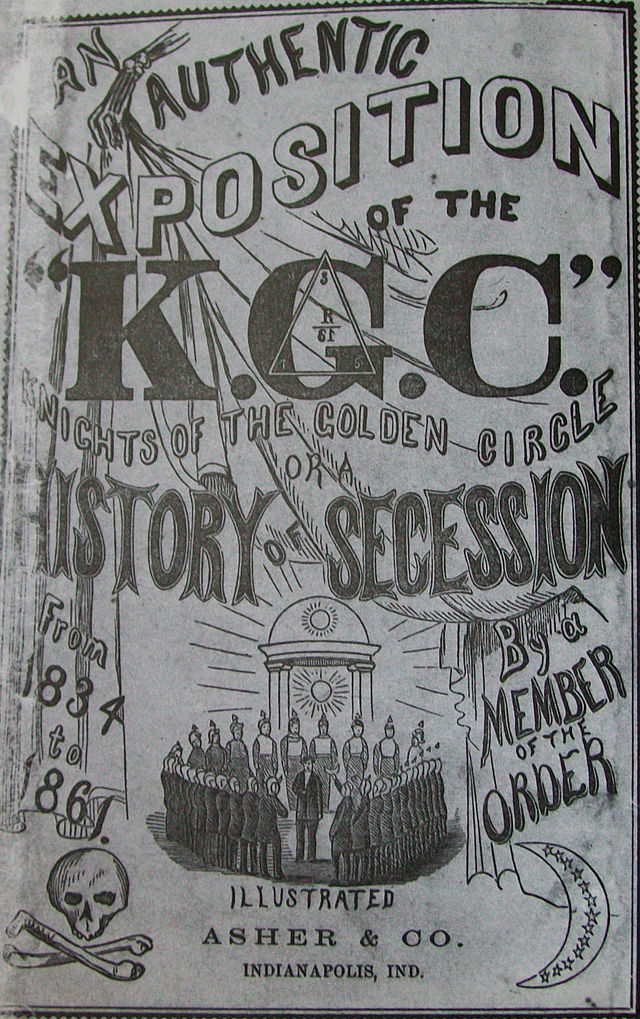

This was evident in the Presidential Election of 1860. This race featured four candidates: Abraham Lincoln for Republicans, John C. Breckenridge for Southern Democrats, John Bell for the Constitutional Unionists, and Stephan A. Douglas for Democrats. In San Antonio, Bell and Breckenridge had the most active support. Those who supported Bell did so because they primarily believed in the preservation of the Union. Although they strongly disfavored secession, they refused to side with Republicans or Democrats on the issue of slavery. Those who supported Breckenridge believed in the state’s right to defend the institution of slavery, and at that time, they believed that the South would not secede under Breckenridge due to his pro-slavery platform. Amid Breckenridge supporters were the Knights of the Golden Circle.13 The Knights of Golden Circle (KGC) was a prominent military secret society founded throughout the South that historian James Wallace relates in his book that a member described its purpose as that the KGC “stressed the necessity of secession… The purpose of the organization, as set forth by a member, was that…’ to bring about Secession, and all its weight was thrown into that movement.'”14 The KGC is said to have influenced the public opinion of San Antonians so much, that the results of the 1860 election featured 726 votes for Breckenridge and only 290 votes for Bell.

Once in San Antonio, Anderson purchased a large ranch and began breeding horses that he planned to sell to the United States Cavalry. He also built the still-standing Argyle Hotel.15 According to historian John Kerr, the ranch was 128 acres featuring a two-story raised beautiful home that had guests such as Robert E. Lee over frequently for dinner.16 Settled into his new Texan home, it was not long before Anderson involved himself in local politics. Anderson commented that the KGC’s fundamental principles were “to preserve and extend American Slavery; that Republicanism had, in its experiment, proved a failure; that legalized oligarchy, or, perhaps, a monarchy, with hereditary-titled orders, were the only class of institutions suited to the wants of the slave states.”17 By this, Anderson aimed to mock the KGC’s purpose.

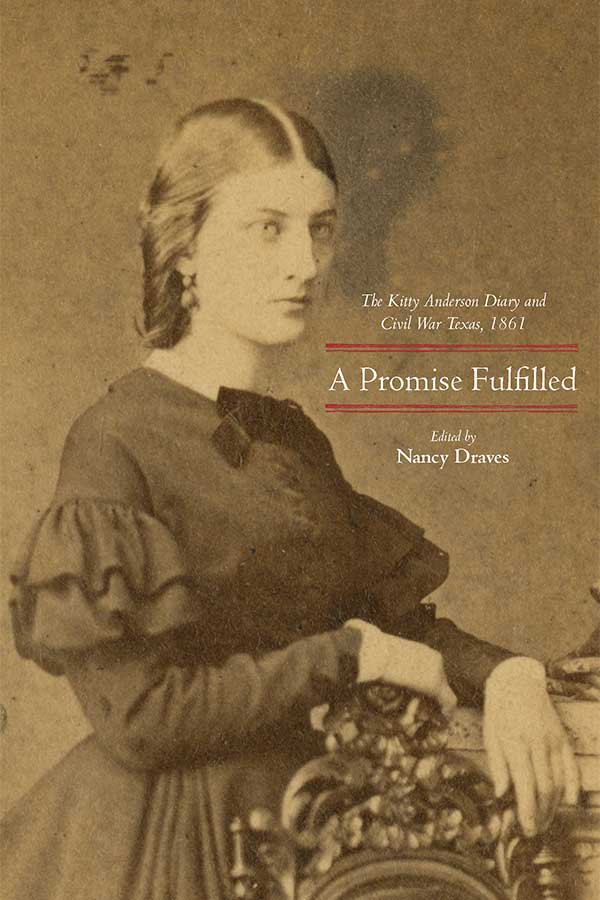

Due to his background in politics and strong beliefs about the preservation of the Union, Anderson rapidly was known for his pro-Union sentiments. Kitty Anderson, Charles’ daughter, recounts in her diary that “Boldly, fearlessly [her] Father has expressed himself always…”18 Anderson’s voice would be heard in front of the Menger Hotel Saturday, November 24, 1860, during a general mass-meeting in which both Unionists and Secessionists voiced their opinions. Anderson could not have known that this event would change the course of his life. There, in front of the crowd, Charles Anderson proudly declared that he opposed secession and boasted his beliefs on the preservation of the Union.19

On February 23, 1861, the San Antonio city election voted on the issue of secession with anti-secessionist winning 562 to 535. Despite the close vote, the majority of San Antonians were against secession. However, on March 2, 1861, Texas officially declared itself seceded from the Union and a part of the Confederacy.

Quickly, Anderson rushed to sell his house, horses, and land, as he was deemed an alien to the State of Texas for his pro-Union sentiment, and he was forced to move within forty days. This came shortly after Texas officially seceded from the Union, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis signed into law on August 8, 1861, that men ages fourteen and up who supported the Union and did not leave the state in forty days would be labeled an enemy alien that would be arrested and imprisoned.20 Kitty recounts in her diary, “Our Texas property all gone, our cattle, horses, house, and home all sold, for much less than their true value…”21 Right before leaving, Anderson made a point not to sell his slaves, but to free them. The family prepared to leave for Brownsville, Texas, when they were intercepted by two Confederate soldiers sent by Col. Henry E. McCulloch and forced to come back to San Antonio. Once in San Antonio, Anderson was offered parole, but he refused it. Anderson, along with his family was held at the Menger Hotel until Col. McCulloch allowed for his family to travel to Brownsville without him.22

A month into his imprisonment, Anderson conducted a scheme to escape his imprisonment at Salado Creek by tricking his guards into believing he was going to bed before escaping out the back of his tent and running through the Salado Creek barefoot at night. With help from a friend, Anderson rode on horseback 140 miles toward the Rio Grande River, and then crossed into Mexico.23 Historians Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves write of this, “After he crossed the river into Mexico, he shouted at the top of his lungs, ‘God and liberty.'”24

Charles Anderson was a man loyal to his country even in the face of imprisonment and loss. He went on to rejoin his family in Ohio and led the 93rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry of the Union Army.25 His story is an example of the conditions Unionists in San Antonio faced as they stuck to their ideas of Unionism and preservation of the nation. Charles Anderson is the standing legacy for an honorable San Antonian who lived during the American Civil War.

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), xiv. ↵

- James O. Wallace, San Antonio During the Civil War (San Antonio, St. Mary’s University, 1940), 16-20. ↵

- John C. Kerr, The Argyle of San Antonio (Texas, Texas A&M University Press, 2019), 4. ↵

- John C. Kerr, The Argyle of San Antonio (Texas, Texas A&M University Press, 2019), 5. ↵

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), xvii. ↵

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), xix. ↵

- John C. Kerr, The Argyle of San Antonio (Texas, Texas A&M University Press, 2019), 5. ↵

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), xvii-xix. ↵

- John C. Kerr, The Argyle of San Antonio (Texas, Texas A&M University Press, 2019), 6-7. ↵

- James O. Wallace, San Antonio During the Civil War (San Antonio, St. Mary’s University, 1940), 1. ↵

- Kenneth Mason, African Americans and Race Relations in San Antonio , Texas, 1867-1937 (New York, Garland Publisher, 1998), 11. ↵

- James O. Wallace, San Antonio During the Civil War (San Antonio, St. Mary’s University, 1940), 5. ↵

- James O. Wallace, San Antonio During the Civil War (San Antonio, St. Mary’s University, 1940), 20-21. ↵

- James O. Wallace, San Antonio During the Civil War (San Antonio, St. Mary’s University, 1940), 17. ↵

- Clinton P. Hartmann, Anderson, Charles (1814-1895) (Texas: Texas State Historical Association, 1952), 1. ↵

- John C. Kerr, The Argyle of San Antonio (Texas, Texas A&M University Press, 2019), 10. ↵

- James O. Wallace, San Antonio During the Civil War (San Antonio: St. Mary’s University, 1940), 17. ↵

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), 4. ↵

- James O. Wallace, San Antonio During the Civil War (San Antonio, St. Mary’s University, 1940), 23-24. ↵

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), xv. ↵

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), 1. ↵

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), 14-20. ↵

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), 68-71. ↵

- Kitty Anderson and Nancy Draves, A Promise Fulfilled: The Kitty Anderson Diary and Civil War Texas (Texas: Texas Tech University, 2017), 71. ↵

- Clinton P. Hartmann, Anderson, Charles (1814-1895) (Texas: Texas State Historical Association, 1952), 1. ↵

4 comments

Eugenio Gonzalez

This article is exceptionally well-written and engaging. It’s both captivating and informative. The influence of the City of San Antonio over its three-hundred-year history is truly remarkable. Your portrayal of the issue of secession in Texas suggests it was a contentious and unpopular topic, dividing opinions.

Carlos Hinojosa

I’m a San Antonio native and have lived here my whole life yet I have never heard of this story. I’m a proud Texan but my city will always come first for me, even if we have questionable mayors sometimes. However, my whole life I have heard very little about the civil war except the bare minimum from high school. I don’t know if that’s because we live in the south or if that’s just normal but to me it seems like no one wants to talk about even my family. Anyways, a very well-made article and I hope to read more. Also, San Antonio should have been the capital city.

Seth Roen

It is incredible how influential the City of San Antonio has been throughout its over three-hundred-year history. And how divided the state was during the secession movement that led to the civil war. From how you wrote, the issue of secession in Texas was rather unpopular and divided. Just imagine if Texas had factions fighting one another during the Civil War.

Madeline Chandler

This is such a well written engaging article. Very captivating and informative. I honestly have not heard of Charles Anderson and in this much detail. It is so interesting to me that he had a horse farm in Texas. I have horses, so I thought that was so interesting. Yet, what is even more captivating is that he had to sell everything and leave because of his Pro-Union choice. Job well done! Enjoyed it!