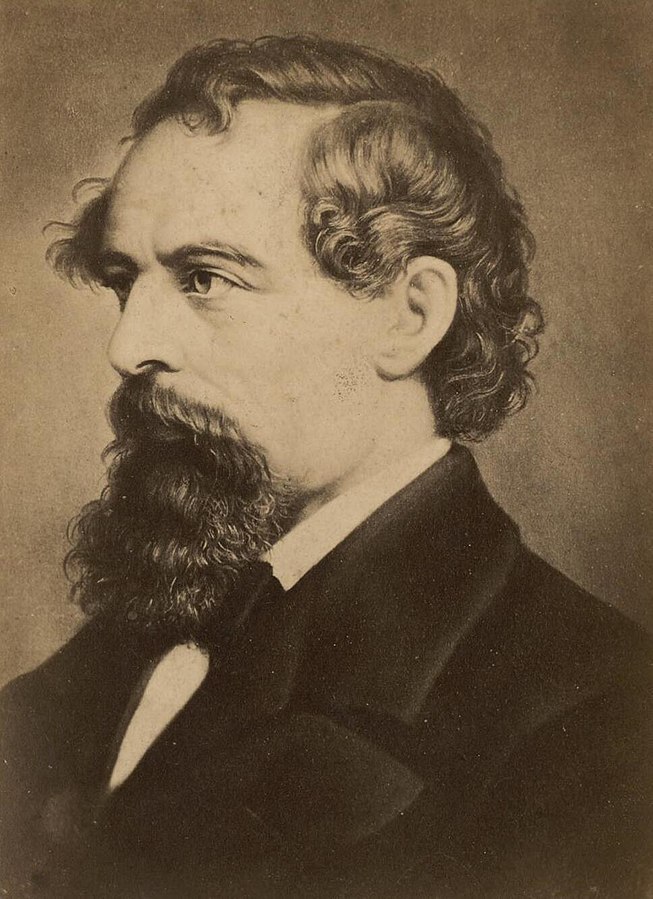

A distinctive quality of a genius is the genius’ ability to retain information and the ability to recount memories in a picturesque manner. Dickens is highly regarded as a literary genius. With his impressive memory to recall even the smallest details, to being able to sprout his stories to life with eloquent storytelling, one may think such talent would be recognized and exploited; however, Charles’ precocious talents were blockaded by the misfortunes of poverty. Dickens’ rise out of poverty is defined by risking discomfort and taking advantage of even the smallest of opportunities that render exposure to raw talent.

Charles’ talents were transparent starting at a young age. He would write his own plays and act them out, such as Misnar, The Sultan of India, where he depicted himself as a demon/monster fighting prince.1 The bedtime stories told by the young maid Mary Weller were vividly etched into his memory.2 These stories had notable influence on his creative imagination due to the tactic Mary Weller used of connecting these accounts with people he knew.3 His parents often struggled to pay the bills due to their investment in their child’s education, but proved to pay off in the future. In addition, despite his lively talents, he suffered from seizures doctors dubbed “colic.” Charles and his father would occasionally go on walks in the city of Rochester, and every time, Charles would wish to own an elegance house, such as the one on the top of Gad’s hill. The house was of great significance to the writer by calling it a “point of convergence between his past, present, and future.”4 For Charles, this place was the very essence of happiness. His family’s move to 18 St. Mary’s improved the quality of his education substantially. “The Brook” was a place that cultivated and harnessed young Charles’ writing abilities. Here, Charles and his sister went to school for the first time; however, it was not the place that most benefited Charles’ education. Rather, it was minister William Giles who saw enormous potential in Charles and made him his pupil. “The Brook” was a different sort of subliminal heaven for Charles… It was a heaven composed of literature. In this specific room that was adjoined to the attic, Charles read the piles of books, essays, plays, and novels that his father acquired and spent a considerable amount of time shut in this small paradise of his as a sort of diversion from his bittersweet move from Ordinance Terrace. However, his dream of becoming a storyteller would appear distant as his family moved to London.

This migration proved to be his fuel and determination for his career. This grim new home reeked of death and debt, and more importantly, his feelings of being neglected an education by his parents was the most pungent smell of them all.5 His father’s debt to shopkeepers and tradespeople almost led to debtor’s prison. However, there was an agreement between the two parties that forced the family to sell their belongings, thus this agreement was something shrouded in ominous clouds that made Charles exceedingly uneasy. Furthermore, his sister Fanny’s success in music rendered him feeling useless, inundating him in a pool of neglect, accompanied by his dreams and ambitions. His illnesses sprouted once again, and his education was hindered due to having to work to assist with the family debt. His agony and sorrows drew even worse as he had to resort to working in a boot-polishing factory; even so, his efforts to help with the family debt seemed futile. This experience was soul-breaking for Charles. Eventually, his father’s debt was up to his neck and thus was taken to Marshalsea Prison. His father was a savior to Charles; he was always on his side and portrayed an immeasurable amount of compassion and affection for his son, so his father’s imprisonment left Charles heartbroken, to say the least. In result, the family lost all of its belongings, including the precious books Charles was so fond of, and they moved into the prison. Ironically, they were better in the prison than they were for some time.6 Charles’ isolation and separation from his family due to his 12-hour shift occupation at Warrens was seemingly everlasting. Charles essentially was his one and only support, and received no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no support, from anyone that he can call to mind.7 Despite being in such wretched conditions, Charles eagerly listened to the stories his mother told about the prisoners, in which he fabricated a character and story for each one.8 After three months of imprisonment, Charles’ father devised a plan to be released from prison. This plan consisted of retiring from the Navy due to medical conditions and applying for a pension. He was released from prison,; however, his pension was to be granted in a year. Life was still in shambles for Charles since his days working at Warrens were seemingly everlasting, yet the mass of his suffering derived from the absence of education. His pinnacle of agony peaked when he attended his sister’s concert in which Fanny received a silver medal from the King’s sister. Dickens could never imagine himself in such righteous light and he could never even fathom being held in such high regard.9

At last, his father received the pension from the Navy, so he used it to send Charles to the Wellington House Academy, which overjoyed Charles. This marked the end of his seemingly innumerable days obscured by dark clouds that cast a gloom over his career, which oddly enough was only 13 months long, yet yielded a millennium of haunting vivid memories. With this new start in life, he swore to not bring up his past. His father took up journalist jobs and was a huge influence to Charles. The newspaper company his father was working for was met with a recession, thus his father lost his job, which also meant an abrupt end to Charles’ education at the Wellington House academy after two years.10 Nevertheless, at fifteen years old he proved to be exceedingly proficient in academics, most notably at writing. After spending two years at the Wellington House Academy, he became a young reporter at the Doctors’ Commons. He did not disappoint, despite initial judgement, and was idolized for his reporting. In addition, Charles fell in love with one of his sister’s friends, Maria, where exchanging gifts deepened the growing love they felt for each other; however, this fantasy crumbled when Maria’s family found out that his family’s past was blighted by debt. Shattered by this romance, Charles completely invested himself in writing and his job as a reporter. Furthermore, his efforts paid off as he was offered a job for a newspaper called Mirror of Parliament. He was impressively skillful with his ability to convert boring notes about politics into lively articles. After his debut at Mirror of Parliament he was offered even more reporting jobs. Still, despite his overwhelming success, he was more interested in writing his own fictional stories. Through observation of the streets of London and his imaginative mind, he would create stories in his head.

One day, Charles dared to submit one of his manuscripts to the Monthly Magazine, which was created when taking one of his walks around the streets of London. Having dealt with rejection from Maria and an apparent rejection from Chronicle, he “…stealthily one evening at twilight, with fear and trembling, into a dark letter-box…” submitted his manuscript.11 He had used a sort of pen name, Boz, which was used for the off chance that his story was not favored. But to his surprise, it was quite the contrary. Londoners loved how realistic his characters were and they especially loved his humor. Glimpses of his dream of becoming a storyteller were finally beginning to take off. He began working for a new editor named Hogarth, whom greatly believed in Charles and wrote a series of sketches. Their affinity was so close that Charles even married Hogarth’s daughter, Catherine. In 1837, his first book, Sketches By Boz was published. And thus, this was how the literary genius’ career blossomed. That righteous spotlight was finally on him and his talents discovered.

Charles landed multiple jobs after him being published. In addition, he and his wife bore children. Charles eventually broke away from writing comedies and focused on writing stories that mirrored the conditions that the poor of London experienced and what he experienced as a child in Victorian England. His fans were not initially satisfied by this, but they soon realized the message and meaning behind such unfortunate stories. In conclusion, Charles reached his many aspirations in life: love, wealth, becoming a published author, and even inhabiting that eloquent house on top of Gad’s hill with his new family; all of which were acquired by taking even the smallest opportunities. Unfortunately, Charles brought upon his own ruin by breaking his marriage with his wife for an actress half his age after twenty-two years of marriage.12 Looking back, Charles states he does not resent the dark episodes in his life, since they played a major contribution in molding him into the person he is known for, even to this day.13

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dickens: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 35-36. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 37. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 37. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 32. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 47-48. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 56. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 56. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 57. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 59. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 62. ↵

- Michael Slater, Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing (New Haven : Yale University Press, 2009), 40. ↵

- Lucy LaFarge, “The Workings of Forgiveness: Charles Dickens and David Copperfield,” Psychoanalytic Inquiry, n0. 29 (2009): 362-373, 372. ↵

- Keith Hooper, Charles Dicken: Faith, Angels and the Poor (Oxford : Lion Books, 2017), 60. ↵

3 comments

Francisco Cruzado

I liked a lot this article, and I value the intriguing retelling of Dickens’ life, and the slight insight into the idiosyncracy of the author in regards to the unjustice in which many people lived during XIX century England. For example, by 1880, 7000 noble families (less than 0.1% of England’s population of that time) held close to 80% of the agricultural land. Additionally, the top richest 1% of England, by 1810, held almost 60% of all private property, keeping similar figures for the rest of the century (in 1900, the percentage had grown to 70%). Dickens was, I think, a brave man who had no fear in speaking against the abuses of which the poor were victims. He may have never come up with a structured ideology or a political plan for reducing poverty, and he may have fallen too in the mischievous idea of philantropy as a great solution for inequality (as in A Christmas Carol), but it is undeniable that he did have the bravery to speak out loud about the then-current state of things.

Roberto Rodriguez

What an article! Descriptive and very interesting topic! I have always admired Charles Dickens’ works because even reading them now in the 21st century they still hold a lot of value and are very good. It is amazing and awe-inspiring how much he had to overcome to get where he is placed in history today, as one of the best (if not the best) authors of all time. It is great to know that he continued to work hard to pursue his dream, even when it was exceedingly difficult to do so.

Steven Clinton

Great Article! Charles’ life early on was full of hardships but his desire to succeed was insatiable. Through thick and thin Charles continued to pursue his dreams of success and that would prove to work in his benefit. Perseverance was key for Charles success. Many people lack the perseverance to recover from life’s adversities. Its unfortunate because everybody want to be successful but not everybody wants to put in the hard work. Fortunately for Charles, he understood this and still pushed forward.