Communication is something that is a part of our daily lives. If people want to communicate, they will pick up the phone and call or text the person they’re trying to reach. Imagine being a thousand miles away and trying to communicate in the 1830s. Unfortunately for Samuel Morse, a tragedy happened in his family, and it sparked Samuel to revolutionize communication. Samuel had always been into art. He was an artist and painted for many years. When he was in Washington, he got a letter from his father about the passing of his wife. After losing his wife, Samuel traveled to Europe for an extended stay to grieve. While traveling back to the United States, Samuel heard about electromagnetism on the boat ride back.1

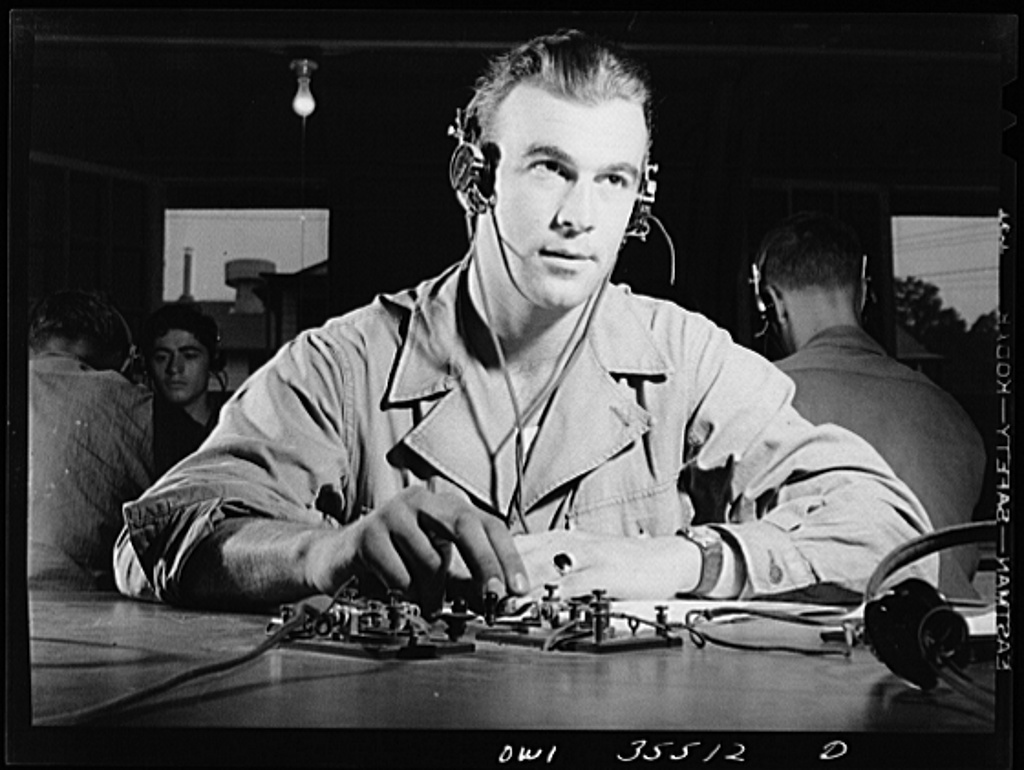

The year was 1832 and conversations were going around about an electromagnet that was newly developed. This caused Morse to wonder: “Why intelligence may not be transmitted instantaneously by electricity.”2 He realized that he could create an electromagnetic telegraph. Since studying at Yale, Samuel was a little familiar with electricity. Samuel knew there was already a telegraph but it wasn’t practical and he wanted to create something more practical, not one that had twenty-six wires per letter. He started to work away. First, he created a machine. This machine was a sender and a receiver. After much experimentation with Joseph Henry’s magnet, Morse was able to use Joseph’s magnet to help create the telegraph.3 After Samuel had been working on this transmitter for many years, he realized that he needed to create a code of some kind to communicate signals. He ran into many roadblocks along the way. He had an idea and was in the process of creating a code to make communication easier, but he didn’t have the knowledge or resources available to continue to create what later on would become Morse Code.4

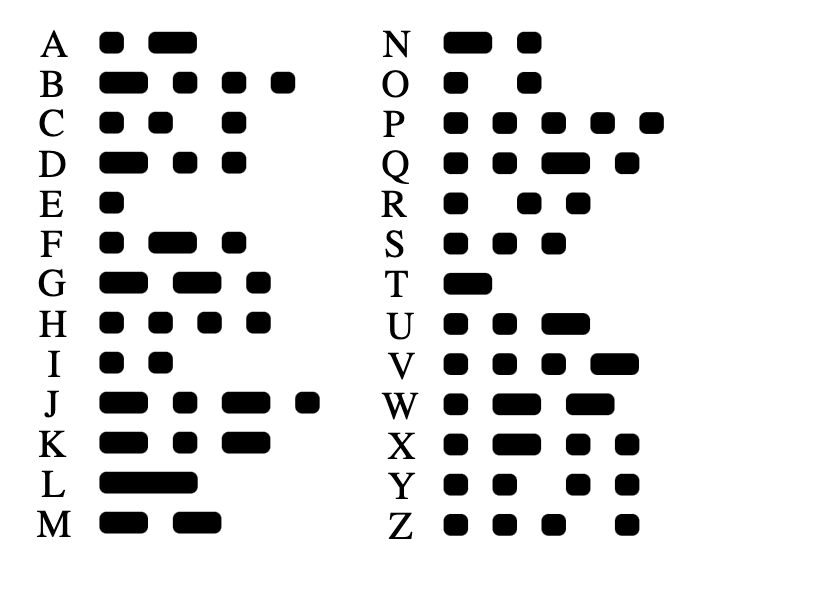

Samuel was an artist; he didn’t have the scientific knowledge to work in the field of technology and he ran into technical problems that stumped him. In 1837, he gave up painting to work full-time on the telegraph, submitting a provisional notice at the patent office in Washington, D.C.5 Shortly after Samuel gave up painting and focused on the telegraph, he met two men at the University of the City of New York. In an article by Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, they mention “Leonard Gale, a chemistry professor, showed Morse how he could improve the electromagnet and battery for the working model of his telegraph. Gale’s friend Joseph Henry offered additional assistance in the area of electromagnetism. Morse also received valuable help from Alfred Vail, whom he took on as a partner in 1837. Vail suggested several practical refinements to the telegraph device itself as well as to the code it used to transmit and receive messages.” After talking with those men, who helped a significant amount in the process of creating Morse Code, Samuel continued to work on it. He started to work on creating “The Code.” With the machine that he had created, he made a system of codes to communicate using dots and dashes. They represented letters, numbers, and punctuation. He had even consulted a typesetting shop to determine the most commonly used letters of the alphabet, in order to make those symbols the simplest. Creating the combination of these dots and dashes became the universal way of communication for telegraphy, or what is called Morse Code today. This helped minimize the number of transmission lines.6

Even though there were European inventors who were also working on creating a telegraph, in 1837, Samuel was ready for public demonstrations. Presenting for an audience at New York University on September 2, Morse successfully presented his telegraph device for the first time to an audience. Following Morse’s public appearance, he reached out to federal government officials regarding more developmental work, but nothing came of him reaching out to officials. In the same year, Morse and Vail applied for a trademark for the telegraph, this time in the United States and England. Samuel wanted to conduct an experimental line that ran from Washington D.C. to Baltimore and asked Congress to help fund it. In 1840, the American patent was approved but the English one was rejected due to a similar project that was developed earlier.7

After years of frustration from Morse not getting funds from Congress, finally, in 1843, Congress acquired $30,000 for the experimental line from Washington to Baltimore. At this time, Morse had been working on creating Morse Code and the Telegraph for about eleven years, and he finally got to send out the first message on the telegraph. In a piece published by Salem Press Encyclopedia, “On May 24, 1844, he tapped out the first message, ‘What hath God wrought!’ and launched a new era in communications.” Vail, one of Samuel’s partners was the person receiving the message from Samuel in Baltimore.8 The message that Samuel sent out was a Biblical passage from Numbers 23:23. According to multiple sources, Morse used that phrase to signify his religious beliefs but to praise the Lord for the ability to create this invention.

The telephone line from Washington to Baltimore lasted until 1847 with the funding coming from Congress.9 Morse had taken his proposal to the government in search of the government to buy the rights for the telegraph, but Congress decided it was best to not continue the partnership. Luckily for Samuel, the telegraph had spread like wildfire and he had many private companies that were interested in helping him fund his telegraph. Samuel, along with other investors, formed a new company, “Magnetic Telegraph Company.” The magnetic telegraph company laid lines for telegraphs in hopes of making a profit. Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce shared “According to an article in Canadian Geographic, the company made only one cent in revenue during its first four days of operation and only $193.56 during the first three months.”10

Just when Samuel thought things were going well and private companies were investing in his telegraph, more problems arose. Charles Jackson, a scientist who had advised Morse in the creation of the telegraph, thought he deserved more recognition for his role in its creation than he got. This led to a problem among Samuel and Jackson that led to court battles. Charles felt that he had contributed to the telegraph and did not get the recognition or credit he deserved for the telegraph. While Charles was a contributor in helping Samuel by giving guidance and helping him design and work on the telegraph, Morse stubbornly refused to give others credit. In an article from Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, they stated that “a few scientistoms were strictly out to profit from his years of hard work. In 1854, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Morse’s patent rights”.11

As time passed, small telegraph companies started competing to take charge of Morse’s invention. Ultimately, smaller companies got bought out by a company called Western Union Corporation. Western Union was able to finally make a profit off of the telegraph. It got to a point where Samuel and his telegraph could no longer hang in the rival with these companies. In 1866, the Magnetic Telegraph Company merged with Western Union as many other companies were doing. Many years later, Morse ended up leaving the business world, but he later joined with Cyrus Field to lay a transatlantic telegraph cable as a project in 1857.12

According to Salem Press Encyclopedia, “By the time of the Civil War, the telegraph was playing an important communications role, particularly in the more industrialized North.” The telegraph played a big role in communication in the 1800’s. It helped with the role of the railroad along with other social and economic impacts in the world.13 With the telegraph, the expansion of the railroad across North America made communication easier and faster over a vast area of land. Another component that the telegraph helped with was modern-day time zones. Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce made a good statement about the benefit of the telegraph, “one significant consequence of this new attitude was the creation of time zones in the United States and Canada. Before the invention of the telegraph, most cities kept their own time based on the position of the sun at noon. A standardized time schedule, presented less confusion and less accidents.”14 The invention of the telegraph had a big impact on the world in more ways than Samuel knew at the time. It helped people feel less isolated from each other and the rest of the country. People were now able to find out information about what was going on around the world.15 Morse’s telegraph was the main source of rapid communication until the telephone came into use.

- Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, eds., “Samuel Morse,” in Business Leader Profiles for Students, vol. 1 (Detroit, MI: Gale, 1999). ↵

- “Samuel F. B. Morse Opens the First U.S. Telegraph Line,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- “Samuel F. B. Morse Opens the First U.S. Telegraph Line,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- “Samuel F. B. Morse Opens the First U.S. Telegraph Line,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- “Samuel F. B. Morse Opens the First U.S. Telegraph Line,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, eds., “Samuel Morse,” in Business Leader Profiles for Students, vol. 1 (Detroit, MI: Gale, 1999). ↵

- Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, eds., “Samuel Morse,” in Business Leader Profiles for Students, vol. 1 (Detroit, MI: Gale, 1999). ↵

- “Samuel F. B. Morse Opens the First U.S. Telegraph Line,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- “Samuel F. B. Morse Opens the First U.S. Telegraph Line,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, eds., “Samuel Morse,” in Business Leader Profiles for Students, vol. 1 (Detroit, MI: Gale, 1999). ↵

- Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, eds., “Samuel Morse,” in Business Leader Profiles for Students, vol. 1 (Detroit, MI: Gale, 1999). ↵

- Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, eds., “Samuel Morse,” in Business Leader Profiles for Students, vol. 1 (Detroit, MI: Gale, 1999). ↵

- “Samuel F. B. Morse Opens the First U.S. Telegraph Line,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, eds., “Samuel Morse,” in Business Leader Profiles for Students, vol. 1 (Detroit, MI: Gale, 1999). ↵

- Sheila Dow and Jaime E. Noce, eds., “Samuel Morse,” in Business Leader Profiles for Students, vol. 1 (Detroit, MI: Gale, 1999). ↵