In the early 1890s, Chicago was rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1871 and became a center of commerce, railroads, and industry. When Chicago was awarded the privilege to host the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, it was a chance for America to demonstrate that it could stand shoulder to shoulder with Europe in art, architecture, and engineering. The city was preparing for world recognition on the world stage in what was going to be a worldwide introduction of American ingenuity. But the problem arose. Four years earlier, Paris had astonished the world and raised the bar with Gustave Eiffel’s iron tower, a 984-foot lattice of steel that changed the possibilities of engineering. The French had set a very high bar, and Chicago’s fair organizers knew they needed something equally bold or more daring. For months, architects and engineers reviewed proposals, towers, domes, arches, and colossal sculptures, but none were sufficiently courageous. After many months of deliberation, nothing had yet been identified that could rival the French achievement. The fair didn’t dare risk opening without a defining symbol. When architect Daniel H. Burnham, director of works for the World’s Fair, expressed his disappointment that no man seemed capable of having the imagination to rival the Eiffel Tower, George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. stepped up. Ferris was a 33-year-old bridge engineer with extensive experience in steel construction and thought he might have the solution. As Ferris later recalled, “We used to have a Saturday afternoon club, chiefly engineers at the World Fair. It was at one of these dinners, down in a Chicago chop house, that I hit on the idea.”1

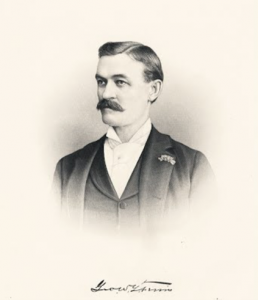

A journalist who met Ferris described him as a man whose presence was as striking as his ideas, noting his “Steel blue eyes of remarkable depth and clarity” and his “quiet, evenly modulated tone” that revealed “unexpected vistas” with every sentence.2 And what greater imagination could there be than proposing the construction of a giant rotating wheel, a machine that would lift thousands of passengers high above the fairgrounds? Ferris sketched out a concept that was absurd and visionary. He conceived a structure so enormous and bold, designed to not just compete with the Eiffel Tower, but to outshine it. He was not thinking of a static monument of iron but a machine in motion, symbolizing America’s progress.

However, obtaining the committee’s permission to actually construct the Ferris Wheel proved to be more challenging than the design process itself.

It was not long before much skepticism caught up to Ferris. Many officials dismissed the wheel idea as unrealistic or simply ridiculous. At a time when even elevators had yet to be normalized and skyscrapers barely existed, the simple thought of suspending hundreds of people in the air seemed to cut close to unsafe or disastrous. Some recommended safer alternatives, favoring traditional ornate towers or grand arches over what they called Ferris’s “mechanical absurdity” and labeling him “the man with wheels in his head.”3

Still, Ferris saw the wheel as the symbol the fair desperately needed, a symbol not just of height but of motion, innovation, and American progress. In June 1892, Ferris presented his proposal to the Exposition’s Ways and Means Committee, a wheel that stood 250 feet high, supported by twin steel towers, and was capable of carrying, at once, more than 2000 people. At first, Ferris’s proposal received mixed reactions.4 Committee members listened, but doubts filled the room, and again, the meeting ended without approval.

Ferris did not abandon the idea; his love for enormous mechanical constructions dated back to his early years in the Carson Valley, even before he ever proposed the wheel to the committee. Growing up on his family’s ranch, Ferris and his older brother spent much of their youth outside, while the ranchers around them constructed water wheels, bridges, and irrigation systems. He was first introduced to engineering concepts by observing these creations. These early experiences, particularly with the big water wheels near the Carson River, may have planted the first seeds of inspiration that would one day become something far greater. “It whetted his appetite for engineering and building things.”5

Rejection only made him more ambitious.

The committee’s disapproval was only the beginning of the pressure. Other engineers proceeded to suggest competing designs, and for a time, the board was in favor of pursuing safer alternatives. Rumors spread that the wheel had been thrown out completely. If Feris wanted his vision to survive, he needed something beyond imaginative design; he needed proof, investment, and the documents vetted by reputations for their opinions that could shut the critics down. Ferris returned with a team and a strengthened plan. He got support from a railway builder, Henry Clay Onderdonk, Judge William Vincent, and other respected figures who supported the project. He obtained preliminary safety evaluations and consulted with engineers at the G.H. Herron Company, which strengthened his case. At the same time, he began recruiting supporters such as the Bethlehem Iron Company of Pennsylvania, which agreed to supply essential steel components if it proceeded. Investors, both major backers and everyday Americans, gradually started investing in what many still considered to be a risky dream. On June 9, 1892, he formed the Ferris Wheel Company, and on November 14, 1892, he founded the Pittsburgh construction company, which would physically build the wheel. Ferris personally contributed 9800$ of the $10000 required for incorporation, almost the entire amount. As the deadline for the fair came closer, he managed design improvements, raised operating funds, sold stock, and kept pushing his ideas forward. Ferris returned for a second chance, this time to appeal directly to Daniel Burnham, the fair’s powerful Director of Works. After reviewing the latest drawings, calculations, and engineering plans, Burnham disapproved because he showed concern about it being too flimsy. Summarized by Jones Lois, Ferris’s defense of the wheel was that it was “an engineering solution, not an architectural ornament.”6

On November 29, 1892, the Ways and Means Committee finally agreed on a conditional approval for the wheel. There was a willingness to embrace the concept, but also no endorsement for construction. As of December 1892, Ferris won, and the full Board of Directors officially accepted the project, but only under complicated conditions. But the victory came with cons. The wheel would have to be built in the dead of winter on frozen ground with a budget of $300,000, which in reality would cost about $392,000 to build. Workers would have only about four months to construct a structure that no one in the world had ever seen. Though Ferris had managed to get conditional approval at the end of 1892, witnesses were still not fully convinced he could deliver on what he promised. The investors were wary of the enormous cost of the unproven and untested design of the wheel. Ferris stated, “The wheel cost in place, 392,000. It will, of course, be a very profitable investment.”7 The exposition leadership asked why the fair should risk its reputation on a rotating structure when more stabilizing monuments, such as towers, arches, and domes, have already been shown through legitimate projects capable of success in other lands.

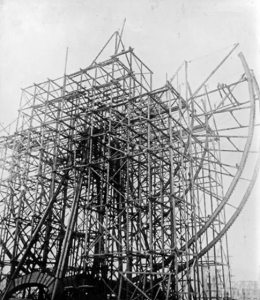

Building on the doubt, Ferris was able to keep pushing forward. In January 1893, Ferris submitted the amended proposal, which included a full engineering assessment, the results of wind load tests, and documents from top engineers in the U.S. who recognized Ferris’s critical design logic. He also raised $50,000 in private backing money raised through sheer tenacity and some of his own assets. With this, a more credible design became clearer, the intensity of the immediate pressure to provide a competing feature to the Eiffel Tower in Paris increased, and by February 10, 1893, Ferris had met the conditions of the earlier approval, allowing construction to officially begin. The frozen ground had to be excavated and reinforced with concrete foundations designed to support over 2000 tons of weight. It took excavations thirty-five feet below the surface and through twenty feet of quicksand and water to obtain a suitable footing. The towers, eight in number to keep cement from freezing live steam, were used.8 Workers raised the 140-foot towers that would support the axle. The axle, which weighed 45 tons, was forged out of steel produced in Pittsburgh and manufactured in both Chicago and Pittsburgh.

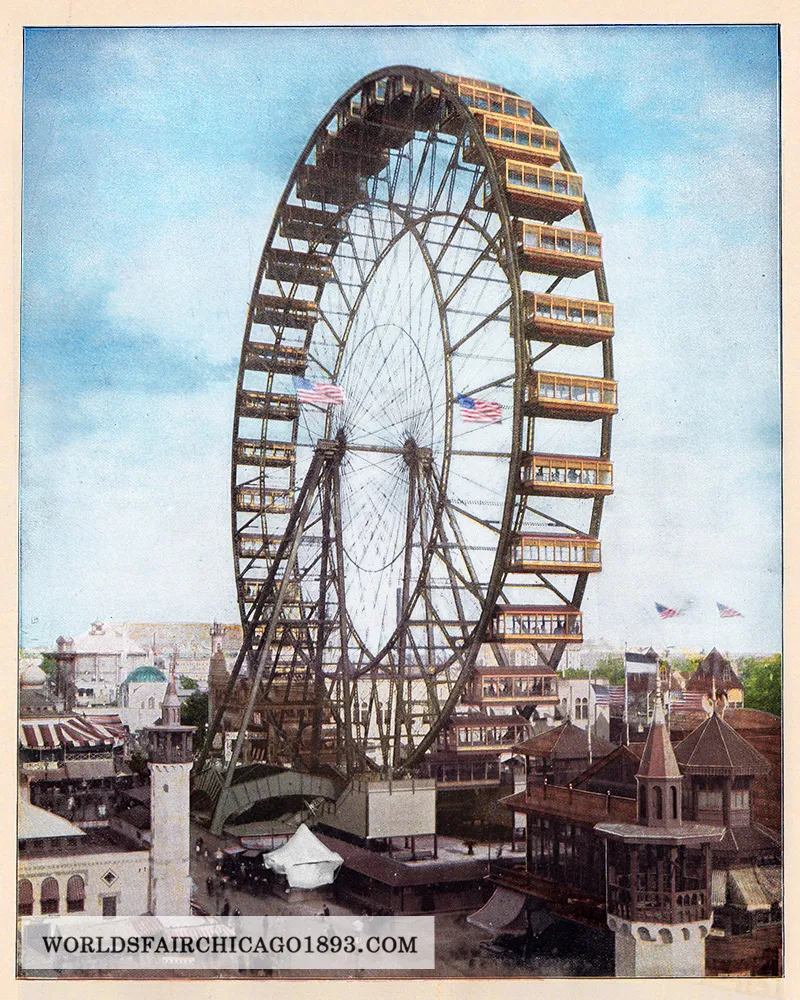

One step at a time, Ferris fought back against doubt from the public. Rivets were tested to withstand double the suggested or anticipated stress loads. The wheel’s forty-eight spokes were assembled like an enormous bicycle, tensioned with steel cables to allow perfect balance to the structure. The wheel began to take shape above the fairgrounds once the rim components were secured in place. It was 264 feet high at its peak.9 Nevertheless, there was still uncertainty. The real trial, the rotation, was still to come. By late June 1893, the final passenger cars had been attached, with electrical lights, heat, and seating for as many as sixty passengers each. In the evenings, an electric light would enliven its silhouette against the town. Day after day, workers continued to inspect the bolts and bearings, again and again, for any imperfection, of which there was none. The structure was complete.

The wheel is up. All that was left was to see whether it would turn.

The long-awaited test came when six passenger cars were attached for the first trial. Before his first trial, workers made sure to tighten the last bolts, engineers checked the bearings again and again, and a crowd gathered in anxious silence. George Ferris himself was in the crowd, his reputation, wealth, and dream all relied on this steel giant before him. Slowly, and almost imperceptibly, the wheel began to move. The massive spoke creaked, and the rim lifted while the cars rose into the air. The crowd gasped, and then was followed by cheers. When the cars reached their highest point at 264 feet above the ground, the view was breathtakingly beautiful. Once the wheel had proven itself, it was open to the public, and Chicago could not get enough. For fifty cents, visitors entered into cars large enough for a whole family, with electric lights and heating. Riders gazed out over the fairgrounds, the city, and Lake Michigan shimmering in the distance. For many individuals, it was the first time they had ever seen the world from such a height. Newspapers that had previously mocked the project were now calling it the highlight of the fair. The Chicago Tribune called it “the most remarkable piece of engineering on the grounds.”10 Foreign visitors saw the wheel like a U.S. version of the Eiffel Tower, as a unique American statement, a monument of movement and imagination. By the end of the exposition, more than 1.4 million people rode the wheel, and it became the iconic image of the event.

A strong storm that threatened to destroy the fair swept through Chicago the night before the grand opening. However, the wheel was still in perfect condition, and on June 21, 1893, the opening ceremony took place on a sunny day, and nearly 150,000 people flooded the fairgrounds.11

Many came with a single goal: to see whether Ferris’s massive wheel could truly turn without collapsing. As foreign tourists rushed into the city, the New York Times reported a huge rush of incoming trains from every direction. At 3 pm the next day, Ferris and the other dignitaries gathered on a platform before the towering structure. As the wheel began to turn, the crowd erupted. Ferris’s invention became the heart of the fair and a symbol of American ingenuity. What had started as George Washington Gale Ferris Jr.’s unlikely dream he had, he overcame doubt, mockery, and engineering risks to become a national success and inspiration.

- Carl Snyder, “Engineer Ferris and His Wheel,” The Review of Reviews (New York), vol. 8, no. 7 (July 1893): 269-270. ↵

- Carl Snyder, “Engineer Ferris and His Wheel,” The Review of Reviews (New York), vol. 8, no. 7 (July 1893): 274. ↵

- Norman D. Anderson and Walter R. Brown, Ferris Wheels. With Internet Archive. New York, Pantheon (1983): 16. ↵

- Richard G. Weingardt, Circles in the Sky: The Life and Times of George Ferris (Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, 2009), 98. ↵

- Richard G. Weingardt, Circles in the Sky: The Life and Times of George Ferris (Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, 2009), 98. ↵

- Lois Stodieck Jones, The Ferris Wheel (Reno, NV: Grace Dangberg Foundation, 1984), 5. ↵

- Carl Snyder, “Engineer Ferris and His Wheel,” The Review of Reviews (New York), vol. 8, no. 7 (July 1893): 273-274. ↵

- Carl Snyder, “Engineer Ferris and His Wheel,” The Review of Reviews (New York), vol. 8, no. 7 (July 1893): 270. ↵

- Carl Snyder, “Engineer Ferris and His Wheel,” The Review of Reviews. (New York), vol. 8, no. 7 (July 1893): 271. ↵

- Chicago Tribune, “In an Endless Circle: The Ferris Wheel Commences Its Journey Through Space,” June 22, 1893, 98. ↵

- Titusville Morning Herald, “Rain Spoiled the Crowd: The Attendance at the Fair Injured,” June 21, 1893. ↵