In 1962, while living in a town outside of Paris, Dr. Charles Henry Kempe was a visiting scholar at Louis Pasteur Institute. One of his daughters had a friend come over, only to see that he had a black eye. After enough questioning, he admitted that his father had inflicted this injury on him. This upset Dr. Kempe, who confronted the boy’s father. His daughter’s memory stated “the boy’s father, very large and slightly intoxicated, next to my father, smaller, but with a commanding presence and a will of iron. He told the father that it was wrong to hurt a child and that if he ever saw unexplained injuries on his son’s body again, he would go to the police.” However, laws protecting children against abuse and neglect were non-existent.1

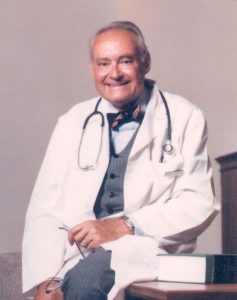

Charles Henry Kempe was born into a Jewish family during a stressing time. Growing up in Germany and watching Nazism form, his family made the decision to leave the country before the war in 1937. Unfortunately, the Kempe family was separated and Henry was taken with a youth group attempting to travel to Israel. The group was captured by Nazis before they could leave Germany, but Henry was released due to his age. “They were such sticklers for technicalities!” his daughter, Allison Kempe, remembers him saying. Luckily, a Quaker organization was able to help him transfer to England after the war began. Later, another refugee organization was able to help him find refuge in the United States. Henry Kempe taught himself English, finished high school, and later went to the University of California. He obtained a medical degree in 1945 from the University of California School of Medicine in San Francisco.2 However, being German, this made Kempe an enemy resident. Graduating medical school, he became a U.S. citizen and joined the U.S. Army. He was assigned to be part of the Army Virology Research Program for two years. This is where he discovered an interest in researching the treatment and prevention of infectious diseases with vaccines. His mentor at this time was Dr. Joseph Smadel, who introduced him to the pox virus. Many of his colleagues told him this work was a “dead end” and that it would not yield any significant importance. Dr. Smadel was able to keep him interested, however, and later he proved that there was significant importance in it. This experience with Dr. Smadel may have influenced Dr. Kempe to push forward in the fact of resistance.3 Later, Dr. Kempe finished his mentorship at Yale University School of Medicine with Dr. Grover Powers. During his mentorship, Dr. Kempe met Dr. Ruth Svibergson who soon became his wife, and over the years of their marriage together they had five daughters.4

Dr. Henry Kempe had a love for many things, including virology. He devoted a huge part of his life to developing vaccines, and he even contributed to the eradication of smallpox. Dr. Kempe established a branch laboratory in Madras, India that developed much of the research for this.5 However, with much of this research, he discovered that the vaccine risk outweighed the disease. Just as he found resistance in researching pox virus, Dr. Kempe found resistance when he presented his case for the elimination of the smallpox vaccine in 1964 at the Society for Pediatric Research and at the American Pediatric Society. As Dr. Vincent A. Fulginiti states, “Dr. Kempe was a crusader, often recognizing facts before the rest of the world was ready to accept them, but that did not deter him from the crusade, and ultimately he was proven right.”6

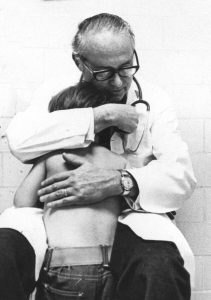

Another strong love of Dr. Henry Kempe was his love of children’s health and their welfare. Dr. Kempe soon became an expert in pediatrics. He would say this was influenced by Dr. Edward Shaw who mentored and guided his studies.3 Dr. Kempe became active in these issues and would lecture on these topics. In 1956, at the young age of 34, Dr. Henry Kempe was asked to be the Pediatric Chairman for the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver as well as a professor. Dr. Kempe pushed for a single pediatric community and invited volunteer faculty to teach in different settings. This was a very different approach compared to present-day teaching in the medical field. Dr. Kempe pushed for conferences and continuing education courses. His students would say he was an inspiration who instilled compassionate, competent clinical care and had the expectations to become superb clinicians.6 He was also known to push his students and colleagues further than their own limitations. Dr. Kempe was capable of seeing the potential in everyone he came across and challenged them to reach it. Dr. Brandt F. Steele stated that the message Dr. Kempe would ingrain in everyone’s mind was “Always try to do more than you think you can. Even though the task may look impossible, you will find that you will have achieved more than you expected to do.”9 Dr. Henry Kempe was known to push those others and ask for a little bit more and to do a little bit better and to everyone’s surprise, they would, even if they did not believe they were capable. His daughter, Dr. Allison Kempe states “He had an almost miraculous way of directing people’s lives…He seemed to see the potential in people that they often did not see in themselves.10

A small but important practice we see today is parents staying with their children at the hospital overnight. This was due to Dr. Kempe’s program that allowed for parents to stay and “room in” during hospitalizations. He saw the significance of decreasing anxieties from children and parents during this stressful time. However, with the mindset to do more and do better, Dr. Henry Kempe’s love of children did not stop at pediatrics within a hospital or clinic walls.4

After working with children and their health, he soon realized a new type of epidemic that needed attention from not only physicians but judges and law officers. As he would later say to colleagues, there was a “hidden epidemic” that needed research and acknowledgment. This hidden epidemic was also known as child abuse. Dr. Henry Kempe reached out to nineteen different experts, including Dr. Brandt F. Steele. In 1975, they traveled to the Rockefeller Conference Center in Bellagio, Italy. During their time there, Dr. Henry Kempe was persistent in laying the groundwork for an article to be published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.12 Dr. Henry Kempe compared how just like smallpox, child abuse was passed on from person to person; however, this could be seen as a way children are raised and later become parents.13 Dr. Kempe noted that “parents may be repeating the type of child care practiced on them in their childhood.14

Together, they formed a study that took place for one year and within 71 hospitals. With this research, they found over 300 cases of child abuse and 33 children had died and as many as 85 children suffered from permanent brain injuries as well. They took this research and later published “The Battered-Child Syndrome” in 1962 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. In the article, they explain that these injuries were usually done by a parent or caretaker. Most of the children reported were very, very young and had chronic symptoms of neglect. This article pushed for physicians to remember their oath to their patients. “Above all, the physician’s duty and responsibility to the child require a full evaluation of the problem and a guarantee that the expected repetition of trauma will not be permitted to occur.”15 Within their findings, they concluded that the “humanitarian-minded physician finds it most difficult to proceed when he is met protestations of innocence from the aggressive parents, especially when the battered child was brought to him voluntarily.16 While today, this may not be the common thought to many physicians, it was widely believed that such an attack on a child could not have happened even if they had the evidence presented before them.

The publication of “The Battered Child Syndrome” brought outrage in different communities. The public demanded that children be heard and demanded new legislation to protect children against abuse. States then called for mandatory reporting of abuse, and by 1967, every state had enacted a form of child abuse and neglect reporting set into law.17 Another way “The Battered Child Syndrome” supported further studies was by compelling the public to push for more research and gain grants to understand the causes of child abuse and different forms of prevention. With this help, they were able to pave the way toward the national level for federal laws. This new knowledge provided understanding for victims, parents, social agencies, educators, law enforcement, and medical and legal professionals. This also led to the creation of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), which was enacted in 1974. This provides federal funding, guidance, investigations, support for prevention, and legal aid to states.

CAPTA now goes further to provide grants to public agencies and non-profit organizations. CAPTA now also provides legal identifiers at a federal level to help children who become victims of sex trafficking.18 “The Battered Child Syndrome” also brought another realization, which is how children develop after they are protected from their perpetrators. With further research thanks to Dr. Henry Kempe and his colleagues, we now have an understanding of the importance of breaking the cycle of generational neglect of children. Together with this publication, they provided stepping stones that created a path to protect children. In regards to all the work, Dr. Kempe later founded the Kempe Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Child Abuse and Neglect in 1972 and later the Kempe Foundation in 1976 that aids in providing advocacy for children and their families.19

Dr. Henry Kempe was recognized for his work and understanding of the smallpox virus and vaccines. He not only raised five daughters with his wife Ruth but loved and nurtured his students to the best of his abilities. He encouraged and inspired them enough that many of his students are now leading figures in pediatrics and other medical fields. Of course, he also demanded excellence from his students, while being involved with their studies. Many of his close friends and family knew him to be creative, energetic, enthusiastic, and devoted.13 One can see how much Dr. Henry Kempe loved the people in his life and how he strove to protect children throughout the world. His daughter, Dr. Allison Kempe states that “his work in child abuse and neglect frequently led him to interface with legal and social welfare systems, and he did what few physicians had done before him: he broke down professional barriers to go wherever the problem was and correct it.” Dr. Henry Kempe was, as stated before, a crusader in the face of resistance and did not shy away from negative feedback. As Dr. Henry once said, “don’t worry about being labeled a do-gooder; just DO GOOD!”21

- Allison Kempe, “C. Henry Kempe, MD: One Man’s Legacy,” Advances in Pediatrics 52 (January 2005): 1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yapd.2005.04.002. ↵

- Allison Kempe, “C. Henry Kempe, MD: One Man’s Legacy,” Advances in Pediatrics 52 (January 2005): 2, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yapd.2005.04.002. ↵

- Vincent A. Fulginiti MD, “PROFILES IN PEDIATRICS II,” The Journal of Pediatrics 126 (1995): 152. ↵

- Henry K Silver, “Presentation of the Howland Award: Some Observations Introducing C. Henry Kempe, M.D.,” 1980, 3. ↵

- Allison Kempe, “C. Henry Kempe, MD: One Man’s Legacy,” Advances in Pediatrics 52 (January 2005): 3, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yapd.2005.04.002. ↵

- Vincent A. Fulginiti MD, “PROFILES IN PEDIATRICS II,” The Journal of Pediatrics 126 (1995): 153. ↵

- Vincent A. Fulginiti MD, “PROFILES IN PEDIATRICS II,” The Journal of Pediatrics 126 (1995): 152. ↵

- Vincent A. Fulginiti MD, “PROFILES IN PEDIATRICS II,” The Journal of Pediatrics 126 (1995): 153. ↵

- R. Kim Oates, “Henry Kempe’s Legacy,” Child Abuse & Neglect 24, no. 1 (January 2000): 314, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00116-7. ↵

- Allison Kempe, “C. Henry Kempe, MD: One Man’s Legacy,” Advances in Pediatrics 52 (January 2005): 6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yapd.2005.04.002. ↵

- Henry K Silver, “Presentation of the Howland Award: Some Observations Introducing C. Henry Kempe, M.D.,” 1980, 3. ↵

- R. Kim Oates, “Henry Kempe’s Legacy,” Child Abuse & Neglect 24, no. 1 (January 2000): 313, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00116-7. ↵

- R. Kim Oates, “Henry Kempe’s Legacy,” Child Abuse & Neglect 24, no. 1 (January 2000): 317, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00116-7. ↵

- Henry Kempe et al., “The Battered-Child Syndrome” 181, no. 1 (1962): 112. ↵

- Henry Kempe et al., “The Battered-Child Syndrome,” Journal of the American Medical Association 181, no. 1 (1962): 112. ↵

- Henry Kempe et al., “The Battered-Child Syndrome,” Journal of the American Medical Association 181, no. 1 (1962): 107. ↵

- “The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act,” Publication Project, 2014, 4. ↵

- Child Welfare Information Gateway, “About CAPTA: A Legislative History,” 2019, 3. ↵

- “About Us,” The Kempe Foundation (blog), accessed March 14, 2022, https://kempe.org/about-us/. ↵

- R. Kim Oates, “Henry Kempe’s Legacy,” Child Abuse & Neglect 24, no. 1 (January 2000): 317, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00116-7. ↵

- C H Kempe, “The 1978 Presidential Address of the American Pediatric Society: The Future of Pediatric Education,” Pediatric Research 12, no. 12 (December 1978): 1151. ↵

15 comments

Sebastian Hernandez-Soihit

Amazing in highlighting Kempe’s pioneering work on child abuse and neglect, and his efforts to change the way society views and responds to these issues. Overall, engaging and inspiring read.

Alexis Zepeda

Hello! Congratulations on a great publication! It is stories such as Dr. Kempe’s that inspire us all to protect those who cannot protect themselves. His reasonings for protecting children remind me of why I chose to pursue a political science career. There are many people who are up against different kinds of issues that they do not understand how to tackle. Dr. Kempe’s story is a reminder to take care of the people around you regardless of your relations to them. Great job!

Juan Aguirre Ramirez

This article was so well-written and intriguing to read Victoria! Dr. Kempe’s efforts to protect children from abuse were truly remarkable, and this is an issue that is far more widespread than most people realize. It’s incredible to think that without his work, legislation may not have been enacted. Congratulations on your nomination and excellent writing! Reading about Dr. Kempe was inspiring; he was a genuine man who had the best interests of children at heart. It’s sad that it took so long for children to gain the right to be stood up for, but the program he established is so beneficial for both children and their families.

Olivia Flores

What an amazing article and such an inspiring man! It is sad to see that it took so long for children to gain the right to be stood up for in the case of child abuse, but this man was destined to make a difference. The program he established is so beneficial for both children and their families. It was so intriguing to read about him. Overall such a great job on this article!

Amy Hotema

I had no idea that doctors used to be prohibited by law from disclosing indicators of abuse. Reading about how Dr. Kempe launched a “movement” that raised awareness of child abuse was really fascinating. while simultaneously working to pass legislation that required doctors to report symptoms when they appeared. This piece and the manner it was written were both fantastic. I have the utmost respect for Dr. Kempe’s commitment to supporting individuals who are unable to speak for themselves.

Lana Garcia

It didn’t occur to me that there was a time where doctors weren’t mandated by law to report signs of abuse. It was extremely interesting reading how Dr. Kempe started a “movement,” that rose child abuse awareness. While also pushing for laws that made sure doctors reported when signs were present. I absolutely loved this article, and the way that the author composed it. I so admire Dr. Kempe for his dedication to helping those who cannot advocate for themselves.

Robert Miller

Hi Victorianna! When I left the military I worked for a little while as an investigator with Child Protective Services here in San Antonio. Reading your article reminded me of why I chose to try that position; protecting those who cannot protect themselves. I was there for about a year but I saw and learned things that I will never forget. Your article on Dr. Kempe was inspiring. I remember that in pretty much all the cases that I investigated that involved school-aged children, the one thing that was in common with all the kids was that they found their school and classroom safe places, which is one major reason why I want to teach. Thank you for your article and I want to share it with some of the investigators that I still have contact with.

Sophia Phelan

He was such an amazing man. And he began an entire movement. Its such an amazing legacy and I hope that we can learn to do good and do what is needed for those who can’t.

Hoa Vo

Dr. Henry Kempe is such an admirable and kind person. He really helped a lot of people and children not just as a doctor but with a kind heart between people. Your article is really well-written and I like the way you introduced your story with the scenario that he visited scholars at Louis Pasteur Institute, noticed the injury of the boy, and tried to protect him, and how worse was laws protecting children during that time.

Grace Malacara

This is a really important issue; child abuse is far more widespread than most people realize, and it is horrible to consider. Dr. Kempe’s efforts to providing child protection are wonderful; he had their best interests at heart and was a genuine man. I’m curious whether legislation would have been enacted if he hadn’t spoken up and pushed for change. Congratulations on your nomination and excellent writing!