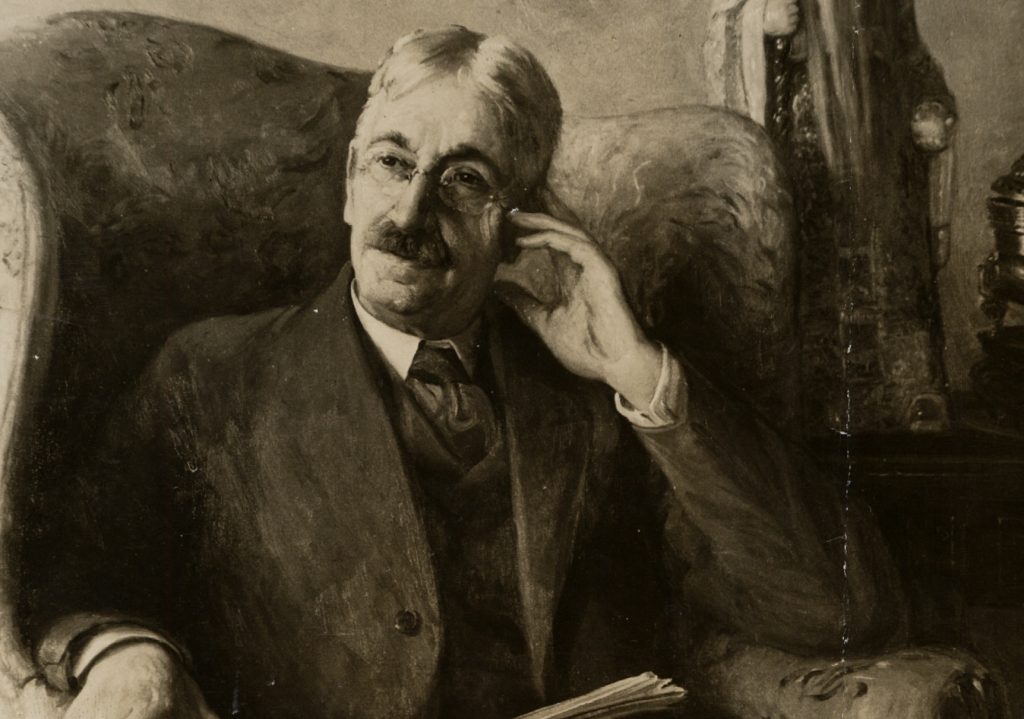

John Dewey was a Vermont resident born from a modern middle-class family on October 20, 1859. Dewey became a philosopher in 1884. He was inspired by G. Stanley Hall and Charles Sander Pierce, who ignited his passion for his future philosophical and educational theories.1

In the year 1896, Dewey, an advocate for education, felt something was missing in the curriculum of students. There was an itch in his brain—a vision for something bigger, something revolutionary. The curriculum of the school played an important role in his idea. John Dewey advocated for more real-life learning experiences and less memorization and listening to lectures. The image Dewey had created in his head was one that would challenge the students, make them ask questions, and make them think on their own. What he had envisioned would soon be fulfilled.

In 1894, the University of Chicago invited Dewey to be the chair of the Department of Philosophy, Psychology, and Pedagogy. After accepting, Dewey knew this would be a turning point in his career. While there, he started to develop his ideas and perceived a broader opportunity for his career. Dewey believed education should be experimental. He liked the idea of problem-solving and knowing that students were physically engaging with their assignments. Dewey believed that if a student is interested in a certain topic, he should be able to gain real-world experience. That way, his learning development would be shaped instinctively. Students should be taught how to actively participate in social and collaborative environments, as well as think critically. Overall, Dewey saw collaboration as a key factor. He argued that students learn better when they work with each other than as individuals. 2

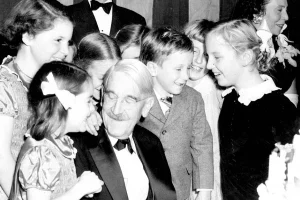

Dewey’s vision came to life when he founded the Laboratory Schools in 1896. This wasn’t just going to shape education. It was the space Dewey needed to further test his methods and apply his theories. The hands-on learning, experience-based knowledge, and experiments had become more than just a dream. 3

In an era where educators focused on memorization and repetition, Dewey emphasized active engagement in education. Philosopher Herbert Spencer, of the same era, believed survival and adaptation were fundamental for education. Dewey’s theory was brought upon by pragmatism — the belief that knowledge comes through doing, not just from reading or listening.

Therefore, Dewey’s reason for enforcing pragmatism comes from experience and problem-solving, the same which he was trying to enforce on the students. Nonetheless, Dewey faced challenges throughout the way. Traditional educators criticized Dewey for his innovative approach. These critics believed Dewey’s approach lacked structure and would introduce disorder in classrooms. Traditionalists said that education should be just facts and knowledge.4

Some religious groups even went as far as to evaluate his method, and said that Dewey’s ideas were secular and were against moral teachings. Furthermore, Dewey struggled with funding because the university was often uncertain if his Laboratory School would succeed. The financial support for the Laboratory schools was inconsistent and hesitant.5

Additionally, there was a lack of staff who understood and were willing to learn this new method of education.6 Teachers were mostly trained in traditional, lecture-based methods, and they found it difficult to adapt to the hands-on student-centered approach that Dewey was introducing. Parents, too, were concerned for their children, worrying his method wouldn’t prepare the child enough to succeed in real life.7

Nonetheless, Dewey kept on.

A new challenge arose: it was to introduce this new method of the student-led curriculum to public schools. As he progressed, the idea of providing the students with freedom and control over their learning approach encountered political issues in larger school systems because it interfered with the traditional structures of public education.8

Later on, his readings got more than just reviews and looks. Dewey’s methods were starting to pay off. The students attending the schools were starting to retain more than that of an average student. Eventually, colleagues started to pick up on his methods. Dewey was gaining attention; of course, it was both negative and positive. His students were memorizing, thinking, questioning, and solving real-life problems. He was still a threat to traditional education.9

John Dewey left the university in 1904. Dewey’s decision was influenced by conflicts with the university’s administration. There was an issue with how the University of Chicago wanted to continue the growth of the Laboratory Schools. This idea was one that Dewey was opposed to. Essentially, University President William Rainey Harper wanted to combine the Laboratory Schools and the education department. Dewey did not agree with these changes. He believed that doing this would completely remove the purpose of his progress in the education model. Harper was looking to centralize and continue the traditional education system. Dewey also wanted the staff at the Laboratory schools to be independent in their teaching methods. The university has other plans in action, plans that would also work against Dewey’s original ideas. The university would impose stricter standards and more control. Dewey saw this as a threat to his career and an offense to his own self, causing him to resign in protest.10

Fortunately, a determined John Dewey did not stop his career. He took his ideas to Columbia University in New York. While there, he published books that continued his theories on shaping the philosophy of education. These books would also shape educational theory for decades to come. In 1916, he wrote Democracy and Education, which is thought to be his most famous work. This book emphasized his major purpose in life: the idea that education should prepare the student for social participation and problem-solving in society.11

In 1934, he wrote Art as Experience. In this book, he focused on applying art and creativity as essential to learning and human growth. In 1938, he published Experience and Education, where he criticized and accentuated that effective learning comes from a balance of structure and experience.

Dewey was inspirational and shifted education with his books. He inspired educators to focus on real-world connections and creativity. Today, project-based learning and group work are modern teaching methods that reflect his beliefs. In modern districts, during teacher training programs, Dewey’s principles are embedded into teachers as they focus on student engagement and reflective learning.12

Dewey’s vision was undeniable and revolutionary, changing education. It is deeply embedded in today’s classroom. In fact, it is the heart of it all.

- “Our History – University of Chicago Laboratory Schools,” January 30, 2025, https://www.ucls.uchicago.edu/about-lab/history ↵

- “Dewey, John | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,” accessed April 9, 2025, https://iep.utm.edu/john-dewey/ ↵

- Stefan Chavez-Norgaard, Katharina Liesenberg, and Michael Lucas, “Scoping Democratic Activities of Collective Problem-Solving,” Problem-Solving at the Community Scale (Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, 2024),http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep65990.5 ↵

- Stefan Chavez-Norgaard, Katharina Liesenberg, and Michael Lucas, “Scoping Democratic Activities of Collective Problem-Solving,” Problem-Solving at the Community Scale (Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, 2024), http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep65990.5 ↵

- Bradley Baurain, “Common Ground WithA Common Faith: Dewey’s Idea of the ‘Religious,’” Education and Culture 27, no. 2 (2011): 85-88, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5703/educationculture.27.2.74 ↵

- “John Dewey (1858-1952): Philosophy and Education – The University of Chicago Centennial Catalogues – The University of Chicago Library,” accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/collex/exhibits/university-chicago-centennial-catalogues/university-chicago-faculty-centennial-view/john-dewey-1858-1952-philosophy-and-education/ ↵

- Stefan Chavez-Norgaard, Katharina Liesenberg, and Michael Lucas, “Scoping Democratic Activities of Collective Problem-Solving,” Problem-Solving at the Community Scale (Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, 2024), http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep65990.5 ↵

- David K. Cohen, “Dewey’s Problem,” The Elementary School Journal 98, no. 5 (1998): 428–430, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1002323 ↵

- Columbia University The Earth Institute and Ericsson, “ICT and Education,” ICT & SDGs (Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2016), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep15879.11 ↵

- Lee Benson, Ira Harkavy, and John Puckett, Dewey’s Dream: Universities and Democracies in an Age of Education Reform (Temple University Press, 2007), https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14bt388 ↵

- Columbia University The Earth Institute and Ericsson, “ICT and Education,” ICT & SDGs (Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2016), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep15879.11 ↵

- Stefan Chavez-Norgaard, KatharinaLiesenberg, and Michael Lucas, “Scoping Democratic Activities of Collective Problem-Solving,” Problem-Solving at the Community Scale (Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, 2024), JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep65990.5 ↵

1 comment

Alejandro Rubio Chappell

I never realized how much of what we see in classrooms today—like group work and hands-on projects—came from John Dewey’s ideas. The story about his pushback against traditional education and even his resignation over keeping his vision alive really stood out. I also liked how the article highlighted his struggles with funding, staffing, and public skepticism. It made his impact feel even more impressive.