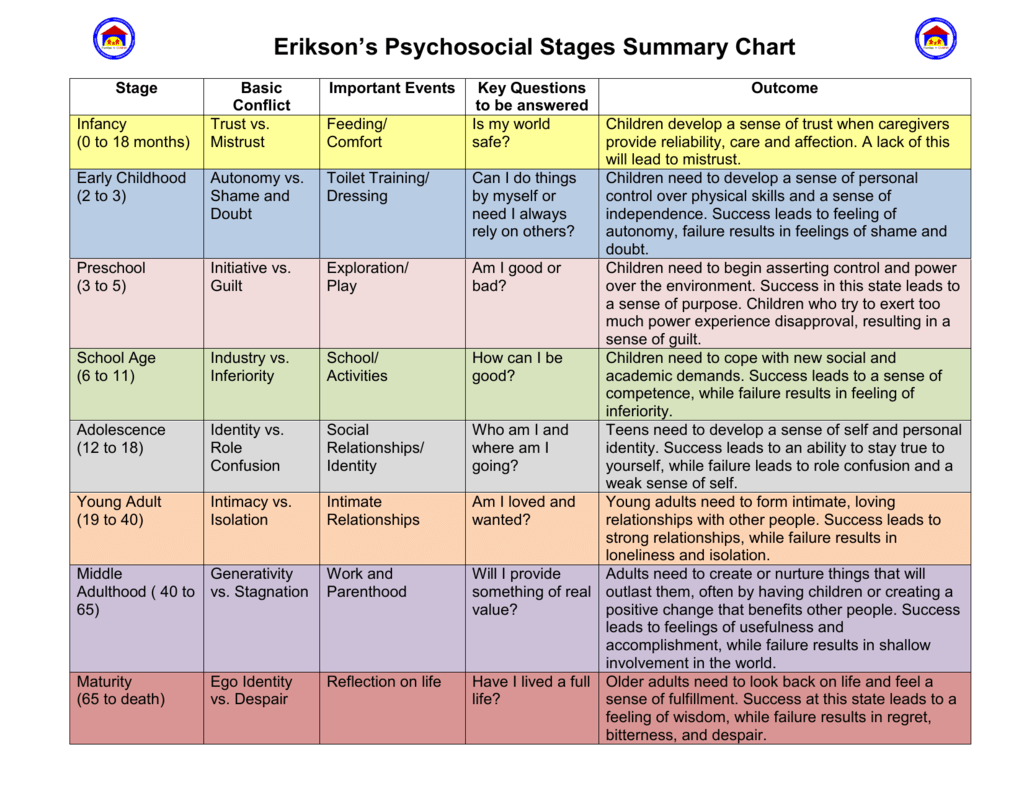

Erikson sought to develop his ideas that the ego, social relations, and biological fulfillment all connect to one another to give us a sense of self — our identity. Erikson explored the psychosocial because of a personal passion he had for it and a commitment to exploring human development.1 A ‘psycholytic identity’ — an individual’s sense of self– is specifically what Erikson had spent his life studying and researching, through very hands-on and personal means, to define what exactly makes our unique identity come to be. This lifelong research led Erikson to his eight stages of development: trust vs. mistrust, autonomy vs. shame and doubt, initiative vs. guilt, industry vs. inferiority, identity vs. role confusion, intimacy vs. isolation, generativity vs. self-absorption, and integrity vs. despair, which take place all throughout one’s life. Before Erikson developed his ideas, Sigmund Freud — whom Erikson was a student of — had already developed his psychosexual theory, which focused on five stages and only in early childhood. Erikson branched off from Freud and his original theory because Erikson believed it was worthwhile to expand the knowledge and understanding of human development beyond the years of early childhood. Erikson’s thought that growth is essential for life and is constant throughout. Erikson didn’t aim to discredit or rewrite Freud’s original theory about the psychosexual; he simply deviated to the path of the psychosocial and expanded from five stages to eight. He de-emphasized the role that sex played as a motivation for certain behaviors and suggested social relationships as a greater motivator. He contributed his own ideas on the topic of the time, which was identity, just as sexuality was the topic for Freud’s time.2

Beginnings in Development

Erikson’s opportunities to venture into psychoanalysis started with Anna Freud accepting him as a fellow candidate to be trained as a psychoanalyst in her small private school in Vienna, Kinderseminar, in 1927, regarding the treatment of juvenile disturbances and delinquency.3 Erikson even gave credit to Heinz Hartmann’s monograph on the adaptive function of the ego, in which Hartmann’s work introduced concepts such as the undifferentiated phase, the conflict-free ego sphere, conflict-free ego development, and primary and secondary autonomy, which ended up foundations to Erikson’s later ideas and theories.3 Erikson claims that,

Even the most venerable training psychoanalyst is (and must be) both welcomed as a liberating agent and resisted as a potential indoctrinator, and thus both be accepted and rejected as an identity model: for in all pursuits which attempt to gain a rational foothold in man’s pervasive irrationality, insights retain an unconscious involvement which can only be clarified by lifelong maturation.5

Seeing Sigmund Freud’s methodology of using only/mostly clinical observation, Erikson wanted to take a different approach for psychoanalysis, which took in more personal data, and he refused to focus only on an exclusive, small group of people — this trend has followed him all throughout his work.6 More notable things that proved significant to Erikson’s way of thinking and opportunity were his excursion to a Sioux Indian Reservation in Dakota (1938), his being invited to participate in a longitudinal study of child development at the University of California at Berkeley (1942), and his children becoming teenagers. During these events Erikson came to a comprehensive understanding of cultural factors in development, focused on the study society [and culture] had on individual’s psychological development — this was the decade in which Erikson started to produce the essays involving the eight stages of development — and his thoughts shifted to focus on the problems confronted by young people, specifically on the idea of identity.7

Mapping the Stages

There were originally only five stages of development focusing on childhood (ages 0 to 18) identified by Sigmund Freud, but Erikson aimed to expand that theory because he believed that development does not simply stop happening after exiting childhood. Erikson believed there is development and growth all throughout a person’s lifetime.

“Each [stage] is categorized by a basic issue conceptualized as a pair of alternative orientations or ‘attitudes’ towards life, the self, and other people. From the way the growing person is able to resolve each issue emerges a ‘virtue’ – a word used in its original sense by Erikson to denote a strength or quality of ego functioning.”8

Freud’s original formulations about the psychosexual were based on the imagery of a transformation of energy, whereas in Erikson’s time, they were guided by concepts such as relativity and complementarity.9 Because the first five stages were developed by Freud, we can not measure Erikson’s formation of these stages, since it does not exist; only his understanding and interpretation do.

Erikson felt as though our identities were a mixture of both positive and negative elements: “Identity means an integration of all previous identifications and self-images, including the negative ones.”10 There are things we want to be and things we do not, or at least we have an idea of what we are supposed to become; either way, we are capable of fulfilling it, given socio-historical situations. Identity has a developmental importance and a societal impact on how we are able to handle certain crises. Hitler’s regime showed just how impactful and susceptible adolescents are to fake ideals and solidifies the idea that society and culture play a huge part in the development of an identity, especially for youths.11

Erikson saw each one of these stages of development as their own “identity crises” because the outcome of each identity crisis was a significant turning point for an individual’s identity. An individual should not think of being located in any one particular stage, but rather sways between at least two of the stages, with the notion that the individual is likely to move into a new stage when a crisis of a higher stage begins to arise.12 “Even though one has resolved his identity crisis, later changes in life can precipitate renewal of the crisis.”13 Erikson had an “epigenetic” view — focusing on things that change gene expression such as lifestyle, environment, and experiences rather than ones due to alterations in the DNA sequence itself — and based what he had to say on representative description rather than a theoretical argument. He wanted to convert a theory of psychopathology and metapsychology into a closely documented view of child development.14

There is a significance of time emphasized in Childhood and Society, according to Robert Coles: “What comes after childhood may well be part of childhood, not because early experiences are endlessly determining, but because we are always what we were, and we always can become what we once were or might have once been,” and I believe these words from Coles were beautifully put and can be well connected to Erikson’s idea that we grow all throughout life and identity having its linear yet shadowing nature.15

His Work Perceived

Erikson’s Childhood and Society introduces the theory of psychosocial development — containing the eight stages — and shows how social and cultural factors affect and influence psychological growth, and claims it’s not completely biological, as Sigmund Freud emphasized. It was immediately published in England (1950) and was received with enthusiastic reception and translated into a variety of languages, such as German, Spanish, and French. It sold steadily for thirteen years after its publication until a second, revised book was published. Childhood and Society became a very well-known and well-identified book in stores and sought out by undergraduate students, graduate students, medical students, law students, psychiatrists, and psychoanalysts alike. It was especially popular and known within the analyst community, which was trying to combine the same ideas Erikson had.16 It was fair to say the book was extremely well-received.

In Richard Stevens’ words, “Erikson’s work is a lineal descendant of Freudian theory.”17 Erikson didn’t make the attempt to redefine the world that is the psychanalytical; he simply contributed to and grew it by introducing a new area of consideration and succeeded in giving us a ‘conceptual itinerary’ to assist us in making sense of the factors that make up our identity.

- Richard Stevens, Erik Erikson: An Introduction (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 43. ↵

- Richard Stevens, Erik Erikson: An Introduction (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 57. ↵

- Erik H. Erikson, “Autobiographic Notes on the Identity Crisis,” Daedalus 99, no. 4 (1970): 735, 739. ↵

- Erik H. Erikson, “Autobiographic Notes on the Identity Crisis,” Daedalus 99, no. 4 (1970): 735, 739. ↵

- Erik H. Erikson, “Autobiographic Notes on the Identity Crisis,” Daedalus 99, no. 4 (1970): 735. ↵

- Richard Stevens, Erik Erikson: An Introduction (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 6. ↵

- Richard Stevens, Erik Erikson: An Introduction (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983): 7-8. ↵

- Richard Stevens, Erik Erikson: An Introduction (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 41. ↵

- Richard I. Evans and Erik H. Erikson, Dialogue with Erik Erikson (New York: Harper & Row, 1967), 13. ↵

- Richard I. Evans and Erik H. Erikson, Dialogue with Erik Erikson (New York: Harper & Row, 1967), 32. ↵

- Richard I. Evans and Erik H. Erikson, Dialogue with Erik Erikson (New York: Harper & Row, 1967), 32-40. ↵

- Richard Stevens, Erik Erikson: An Introduction (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 56-57. ↵

- Richard I. Evans and Erik H. Erikson, Dialogue with Erik Erikson (New York: Harper & Row, 1967), 41. ↵

- Robert Coles, Erik H. Erikson: The Growth of His Work (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970), 119-120. ↵

- Robert Coles, Erik H. Erikson: The Growth of His Work (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970), 138-139. ↵

- Robert Coles, Erik H. Erikson: The Growth of His Work (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970), 118 & 154. ↵

- Richard Stevens, Erik Erikson: An Introduction (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983), 108. ↵

2 comments

Jillian Pierucci

Great words and story you have portrayed to capture the life of Erikson. He was foundational in his contributions to developmental psychology, as you’ve said. Well done, Alayna.

Tessa

“Assembly required”. Great nod to Erikson’s idea that we are continuously creating and redefining our identity.