Prenatal genetic testing is performed to identify any genetic disorders the fetus may have. This is done for the health and safety of the fetus as well as the mother, as there are complications that could occur due to the disorder. The decision to have prenatal testing done should ultimately be that of the parents of the fetus; it being a hefty decision and affects the entire family. However, in some unethical cases, testing is done to no knowledge of the parents, which can severely limit the extent to how much control the mother has to her own pregnancy. Prenatal genetic testing should be a unanimous decision and should only be done when all parties have consented.

Prenatal genetic testing continues to evolve, with more tests being introduced at our disposal. There are different types of genetic testing, which can range from ultrasounds, blood tests, or testing the fetal cells present in the amniotic fluid or placenta. 1 Though this type of testing is not required, it is becoming much more common among expectant mothers. Prenatal tests can be performed at the request of the expecting parents or a medical professional. In some cases, parents choose to not have the testing done considering their circumstances, as well as there not always being a treatment. 2 The testing is informative and can be done to help prepare the parents in case the fetus does have a crucial medical condition, improve the survival rate and the neonatal outcome, and examine the severity of the disorder found. 3

There are several factors to consider when contemplating having the testing done. The invasiveness, the cost, weighing the advantages and disadvantages, and wanting to seek more information regarding the health of the fetus. 4 The invasiveness of a test can also influence the desire for it to be done. Instead of individuals having to undergo these forms of invasive testing, there is another option known as Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT). 5 There are some added benefits that come with NIPT, including the minimal complexity of the procedure, how early the testing can be done during the pregnancy, the high sensitivity, and the lack of physical risks for the fetus. 6 These added benefits, along with the non-invasiveness, should pull more mothers into getting the testing, as opposed to the invasive tests only bringing up more anxiety and added stress. Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing has shown no added physical risk or harm to the fetus or the expectant mother. 7 As the use of NIPT has increased, it has also brought about some concerns. These concerns include how this type of testing can only be performed under certain conditions and circumstances. 8 This test can also be limited to what is being tested for and how it will be used. 9 Due to this, many policy makers are having to make difficult decisions regarding the testing and what the future of the testing will hold. 10 Additionally, these decisions will determine whether the testing should be banned or only allowed for certain uses and whether or not to promote it to the public for these certain uses. 11

Anxiety levels are already high for expecting mothers, who should not have the added stress factors when it comes to thinking about the health of their baby and will, therefore, opt out of getting the testing done at all. At times, the prenatal genetic tests provide the mothers with reassurance as they will know their baby is healthy, which also helps shift their focus from what could be going wrong. 12 The doctor or health care professional would more so recommend the prenatal test if the expectant mother were at a high risk pregnancy. A high risk pregnancy or an indicator a prenatal test should be performed is an advanced maternal age (35 or older), a family history of a genetic disorder, the parent or a family member being a carrier of a genetic anomaly, and abnormal indications in the ultrasound. 13

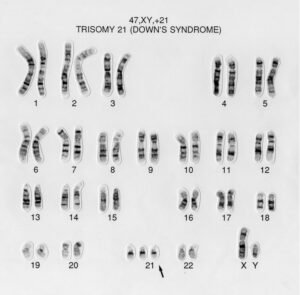

Once the results are in for the test, a health care professional will then deem it appropriate to explain to the expectant parents how to continue with the pregnancy and what their next steps should be. In some cases, depending on the test results, the health care professional will advise to terminate the pregnancy, which is where the ethics of the matter plays a role. As previously mentioned, prenatal genetic tests can determine the medical conditions the fetus has as accurately as possible, though some disorders aren’t revealed through this type of testing. However, the risk factors and number of inherited disorders that can be found during the genetic testing are increasing at a rapid rate as a result of the evolution of testing. 14 For example, Down syndrome, scientifically known as Trisomy 21 due to a third copy of the 21st chromosome, is a common chromosomal anomaly detected at birth. 15 As Down syndrome is a highly variable condition, it is usually not detected during an ultrasound but rather a karyotyping, a chromosomal analysis. 16 In contrast, Tay-Sachs disease, an untreatable and fatal condition, may be a case where the healthcare professional would guide the mother and father in the direction of terminating the pregnancy, as the condition causes neurological disorders as early as the toddler ages. 17 Tay-Sachs disease, however, can’t be determined through karyotyping; it would have to be detected using a Chorionic Villus Sampling or Amniocentesis. 18

Chorionic Villus Sampling and Amniocentesis are just a few types of tests that can be performed on the fetus to determine if there are or will be any birth defects or genetic anomalies. Other prenatal genetic tests include, but are not limited to, maternal blood tests, ultrasounds, karyotyping, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). 19 The type of test that will be used is determined by the kind of pregnancy as well as what the patients and health care professionals want to look for, if anything specific. Of the testing methods mentioned, Chorionic Villus Sampling, or CVS, and Amniocentesis, are two of the more invasive tests, as both require obtaining fetal cells. 20 The maternal blood test screening is an examination and analysis of whether or not the alpha fetoprotein, AFP, is present; this test is normally performed at least 18 weeks into the pregnancy. 21 The presence of this protein can help indicate if the fetus has an open neural tube defect, such as Spina Bifida. 22 Ultrasounds are used during normal check-ups on the fetus as the mother furthers along in the pregnancy, though they may not always be the most accurate form of testing.

The ultrasound shows a picture of the fetus, allowing the health practitioner to determine the size and sex of the fetus as well as ensuring all limbs are forming properly. 23 Lastly, FISH is used if a chromosomal variant is identified, though this is not clearly found using a karyotype, a chromosomal analysis tool. 24 A chromosome probe, which is a piece of DNA complementary to DNA within a gene, is viewed under fluorescent light to determine any developmental abnormalities within the chromosome. 25 All tests come with potential risk factors; however, CVS and Amniocentesis both carry risk for infection and miscarriage, though these tests are performed on a case-by-case basis and under the advising of a health care professional. 26

When it comes down to it, ethics play a role on both sides: the parents and the doctor or healthcare professional. Parents may be drawn away from the idea of prenatal genetic testing due to their beliefs such as their ethical, intellectual, and religious morals. 27 Another factor that can convince the parents to make a decision regarding the test is the family’s history with genetic anomalies. Something that could also affect the parents’ decision to have the testing done can also be due to psychological aspects and a moral examination about how the testing is perceived and how accurate it will be. 28 The public perception of prenatal genetic testing can also influence the patient to have it done or not. As the testing becomes more commonly used, it also becomes more normalized, which is reassuring for many. No matter how evolved these tests are, the public will continuously find a way to find the positive and negative implications of genetic testing, with the negatives far outweighing the positives. These preconceived notions about genetic testing are mainly what drives parents-to-be away from having the tests performed. Though the genetic tests find most of what the outcome of the fetus will be, they will not always be 100% accurate. 29 However, when used most efficiently by physicians, the results can provide enough information for the parents to ensure their child will be thoroughly cared for pre- and post-delivery. 30 How the public views genetic testing can also benefit the parents, as these attitudes can help people approach beneficial things and avoid harmful things. 31 In turn, this can also influence the public and people close to the situation to rethink their negative opinions about it after seeing the positive outcomes and the benefits it entails. 32 Ethics should be concerned when having the prenatal testing done, as the results can severely affect the remaining time of the pregnancy.

Pregnant women already face immense pressure given that they have to make the decision regarding prenatal testing, diagnosis, and, in some cases, the termination of the pregnancy given the diagnosis. It only increases the burden when these women have so many decisions to make regarding the pregnancy, with the added pressure of everyone counting on them to make the “right” choice.33 The ethical issues of prenatal testing comes in many different forms. Firstly, health care professionals have certain responsibilities to perform before going through with the testing, such as obtaining valid consent and knowing how to manage and return the information to the expectant mother and father. 34 Obtaining valid consent is very crucial to whether or not the test should ultimately be done. It is vital that the health care professional also maintain open communication with the patients while also ensuring they understand the level of intricacy the test demands and easing any worries that arise, though getting this consent can be difficult to achieve depending on the complexity of the case and pregnancy risk. 35 Though, depending on the test results and how accurate they are, it may still be hard to determine how much or how little the child will be affected by the diagnosis. 36 Another pressing ethical issue brought about by genetic testing is informing patients of the diagnosis. Returning the information about the results to the patients brings up questions like who should be the one to tell, who they should tell, and when. 37 Some health care professionals will also deem it inappropriate to tell the patients of the diagnosis, as there is not always action to be taken to treat the illness. 38 In addition, the results may further increase the pressure and anxiety of the patient during their pregnancy, given there is no cure for what the outcome will be, though the parents still have the right to know. The majority of parents who have performed the testing, however, would like to know the results, understandably so, to know how they can prepare by making any decisions necessary and/or finding the treatment options, if any. Though if there is any uncertainty with the results or data that is arguable, it should not be returned to the parents. 39 This is because the patients should not be given false results, as it can only lead to miscommunication between the professionals and the patients, as well as even more unnecessary anxiety added to the situation. 40 Patients deserve to know the truth about their future child and should not have to rely on their constant questioning when it concerns their health and safety.

Prenatal genetic testing is still seen as a taboo, or touchy, subject for some. It is also still seen as something with more disadvantages than advantages, which is why many people opt against the testing. Furthermore, patients knowing the outcome of their child can potentially further induce anxiety during pregnancy and confirm that it will lead to long-term effects for the child. As opposed to this, there are many parents who wish to find out the fate of their child in the long run and know the quality of life they will be given. There is no issue with this, as parents-to-be have a right to know, and it is a good way to prepare for a baby if there is a condition found after the tests have been performed. These tests are nearly completely accurate and give parents a sense of certainty and ease in knowing what steps to take next and, if available, finding the appropriate treatment options.

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- Dukhovny and M. E. Norton, “What are the goals of prenatal genetic testing?,” Seminars in Perinatology, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 270–274, Aug. 2018, doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2018.07.002. ↵

- Dukhovny and M. E. Norton, “What are the goals of prenatal genetic testing?,” Seminars in Perinatology, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 270–274, Aug. 2018, doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2018.07.002. ↵

- S. Oliveri et al., “Decision-making process about prenatal genetic screening: how deeply do moms-to-be want to know from Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing?,” BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05272-z. ↵

- S. Oliveri et al., “Decision-making process about prenatal genetic screening: how deeply do moms-to-be want to know from Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing?,” BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05272-z. ↵

- S. Oliveri et al., “Decision-making process about prenatal genetic screening: how deeply do moms-to-be want to know from Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing?,” BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05272-z. ↵

- C. Dupras, S. Birko, A. O. Affdal, H. Haidar, M.-E. Lemoine, and V. Ravitsky, “Governing the futures of non-invasive prenatal testing: An exploration of social acceptability using the Delphi method.,” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 304, pp. 1–10, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112930. ↵

- C. Dupras, S. Birko, A. O. Affdal, H. Haidar, M.-E. Lemoine, and V. Ravitsky, “Governing the futures of non-invasive prenatal testing: An exploration of social acceptability using the Delphi method.,” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 304, pp. 1–10, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112930. ↵

- C. Dupras, S. Birko, A. O. Affdal, H. Haidar, M.-E. Lemoine, and V. Ravitsky, “Governing the futures of non-invasive prenatal testing: An exploration of social acceptability using the Delphi method.,” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 304, pp. 1–10, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112930. ↵

- C. Dupras, S. Birko, A. O. Affdal, H. Haidar, M.-E. Lemoine, and V. Ravitsky, “Governing the futures of non-invasive prenatal testing: An exploration of social acceptability using the Delphi method.,” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 304, pp. 1–10, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112930. ↵

- C. Dupras, S. Birko, A. O. Affdal, H. Haidar, M.-E. Lemoine, and V. Ravitsky, “Governing the futures of non-invasive prenatal testing: An exploration of social acceptability using the Delphi method.,” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 304, pp. 1–10, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112930. ↵

- Oliveri et al., “Decision-making process about prenatal genetic screening: how deeply do moms-to-be want to know from Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing?,” BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05272-z. ↵

- Pivetti and G. Melotti, “Prenatal Genetic Testing: An Investigation of Determining Factors Affecting the Decision-Making Process,” Journal of Genetic Counseling, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 76–89, 2013, doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9498-6. ↵

- Pivetti and G. Melotti, “Prenatal Genetic Testing: An Investigation of Determining Factors Affecting the Decision-Making Process,” Journal of Genetic Counseling, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 76–89, 2013, doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9498-6. ↵

- Pivetti and G. Melotti, “Prenatal Genetic Testing: An Investigation of Determining Factors Affecting the Decision-Making Process,” Journal of Genetic Counseling, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 76–89, 2013, doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9498-6. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- L. M. Carlson and N. L. Vora, “Prenatal Diagnosis,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 245–256, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.004. ↵

- M. Pivetti and G. Melotti, “Prenatal Genetic Testing: An Investigation of Determining Factors Affecting the Decision-Making Process,” Journal of Genetic Counseling, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 76–89, 2013, doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9498-6. ↵

- S. Oliveri et al., “Decision-making process about prenatal genetic screening: how deeply do moms-to-be want to know from Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing?,” BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05272-z. ↵

- A. Maftei and O. Dănilă, “The good, the bad, and the utilitarian: attitudes towards genetic testing and implications for disability,” Curr Psychol, pp. 1–22, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02568-9. ↵

- A. Maftei and O. Dănilă, “The good, the bad, and the utilitarian: attitudes towards genetic testing and implications for disability,” Curr Psychol, pp. 1–22, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02568-9. ↵

- A. Maftei and O. Dănilă, “The good, the bad, and the utilitarian: attitudes towards genetic testing and implications for disability,” Curr Psychol, pp. 1–22, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02568-9. ↵

- A. Maftei and O. Dănilă, “The good, the bad, and the utilitarian: attitudes towards genetic testing and implications for disability,” Curr Psychol, pp. 1–22, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02568-9. ↵

- C. Dupras, S. Birko, A. O. Affdal, H. Haidar, M.-E. Lemoine, and V. Ravitsky, “Governing the futures of non-invasive prenatal testing: An exploration of social acceptability using the Delphi method.,” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 304, pp. 1–10, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112930. ↵

- R. Horn and M. Parker, “Opening Pandora’s box?: ethical issues in prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing,” Prenatal Diagnosis, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 20–25, 2018, doi: 10.1002/pd.5114. ↵

- R. Horn and M. Parker, “Opening Pandora’s box?: ethical issues in prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing,” Prenatal Diagnosis, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 20–25, 2018, doi: 10.1002/pd.5114. ↵

- R. Horn and M. Parker, “Opening Pandora’s box?: ethical issues in prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing,” Prenatal Diagnosis, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 20–25, 2018, doi: 10.1002/pd.5114. ↵

- R. Horn and M. Parker, “Opening Pandora’s box?: ethical issues in prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing,” Prenatal Diagnosis, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 20–25, 2018, doi: 10.1002/pd.5114. ↵

- R. Horn and M. Parker, “Opening Pandora’s box?: ethical issues in prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing,” Prenatal Diagnosis, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 20–25, 2018, doi: 10.1002/pd.5114. ↵

- R. Horn and M. Parker, “Opening Pandora’s box?: ethical issues in prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing,” Prenatal Diagnosis, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 20–25, 2018, doi: 10.1002/pd.5114. ↵

- R. Horn and M. Parker, “Opening Pandora’s box?: ethical issues in prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing,” Prenatal Diagnosis, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 20–25, 2018, doi: 10.1002/pd.5114. ↵