The definition of life’s meaning isn’t something that can be summed up in a flowery sentence that is found on a poster, it is specific to each person and their journey. The meaning of life is something that we, as humans, can spend our whole lifetime defining for ourselves. When it comes to the end of our story, we should be the ones to define what life means to us. Individuals that are suffering from life-threatening diseases that have no cure, such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease, are faced with challenges and the reality that they have a limited time on this earth. While there are limited options for individuals who are suffering, an option that can be explored is medical euthanasia (Ekkel et al., 2022). Medical euthanasia is a treatment plan that provides the patient with a painless way of ending their suffering. The focus of this paper will be on the use of euthanasia for individuals with Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease and the ethical and moral decisions that must address the decline of cognitive ability in those pursuing the procedure.

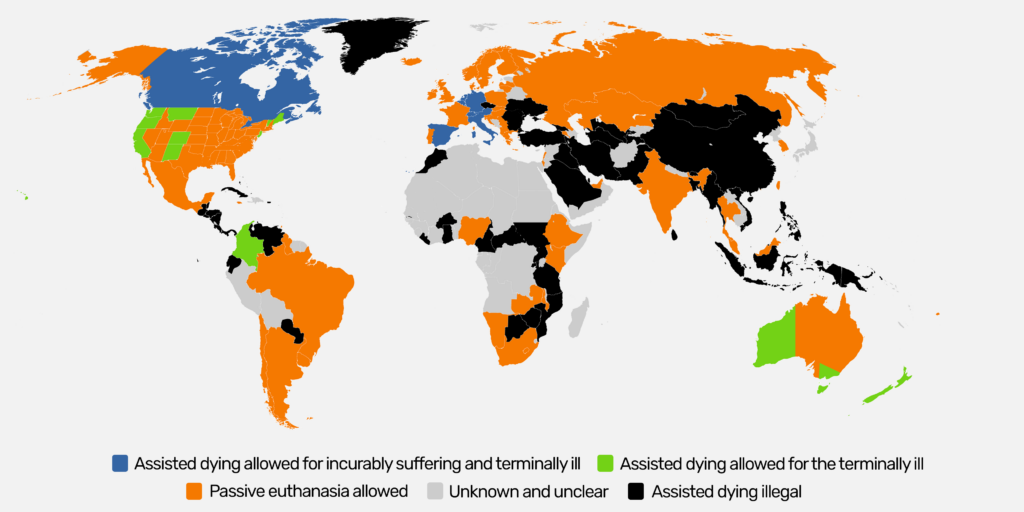

There is an issue with euthanasia for patients with Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease as there is a question of the individuals capacity to request the procedure, and when their quality of life is no longer suitable, therefore their advance directive should be carried out (Theriault et al., 2021). Advance directives are legal documents that allow a patient to express their wishes in situations when they are no longer able to express them. In addition to conflicts where it is legal to request euthanasia, the option is not available in most countries and states. Those who wish to seek these options will have to venture to locations that allow some form of euthanasia (Mondragon et al., 2019).

In discussing euthanasia, the physician’s point of view must also be taken into consideration as they are faced with the challenge of determining what defines the patient’s quality of life. In doing so, they can facilitate the use of euthanasia in good conscious and must be able to have an open conversation without a bias towards their own beliefs. In regards to medical euthanasia, it was found that many physicians do not broach the treatment option of euthanasia and will wait for their patients to explicitly broach the topic (Booij, Engberts, Rödig, et al., 2013).

Euthanasia the practice of ending a life for whom is experiencing extreme suffering while there is no cure based on their advance directives, which can be in oral or written form (BERESTOVA et al., 2019; Booij et al., 2014; Ekkel et al., 2022). There are different forms of euthanasia that are legal across the world. They have different names, but all seek to achieve the end of a patients suffering through intervention: voluntary assisted dying (VAD), medical aid in dying (MAiD), continuous deep sedation (CDS), voluntary active euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide, and physician-assisted death (PAD). In Switzerland, euthanasia is given as a liquid Sodium Pentobarbital that puts the patient into a deep coma within a few minutes and then causes the respiratory system to stop working leading to death (Portacolone et al., 2019). In Sweden, where euthanasia is illegal, CDS, sedation that is paired with the refusal of all fluids, is an option for those who are suffering from specific life-threatening diseases (Lindblad et al., 2010).

While these are viable options for some, there are those who disagree with the availability of such procedures based on their beliefs. Culture is an important part of the discussion of how one should end their life in any circumstances. We can see the relevance based on which countries allow for euthanasia and are considering adapting the practice. In “Islamic, African and Orthodox cultures” euthanasia is highly rejected as it goes again their religious beliefs (BERESTOVA et al., 2019). Western culture in general is more accepting of idea of euthanasia as independence and autonomy is highly valued. For those who support PAD in the USA make it clear that the option should be available but with the understanding that the patient is well informed of all options and are cognitive enough to make their own decision as we deserve the freedom to decide (Mondragon et al., 2019). In a study performed to judge the general population and physicians opinion on the use of CDS on cancer patients and those suffering for neurological diseases, they found the overall positive response to the use of CDS (Lindblad et al., 2010).

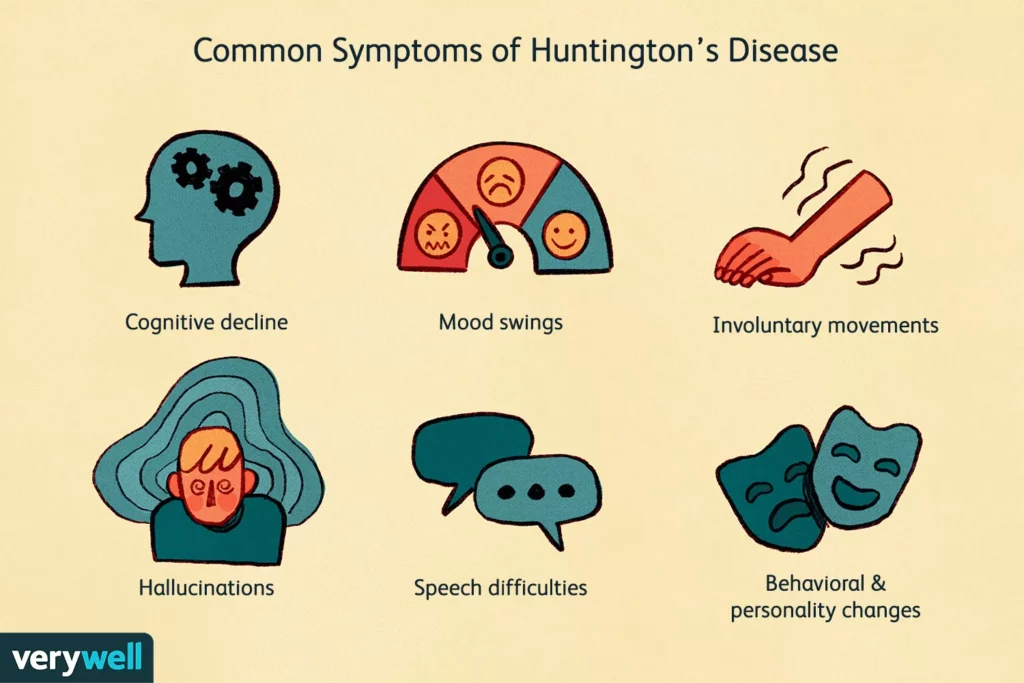

Huntington’s is a neurodegenerative disease that autosomal dominant, only one parent needs to have an altered gene to pass the disease (Ekkel et al., 2022). Diagnosis is usually made around the age of 30 and treatment of the symptoms can last between 15 to 25 years until death. Huntington’s starts with uncontrollable movement of limbs, changes in behavior, and progress to loss of cognitive awareness leading to dementia (White et al., 2022). Treatment options are limited, the medications prescribed ranges from antipsychotic to antidepressants to help stabilize the gradual mood changes, however, there is no medication that is proven to stop the progression of the disease (Ferguson et al., 2022). A study was performed on Huntington’s patients to gather their thoughts regarding the end of their lives, and to gain a better understanding of external factors impacting their want for euthanasia. The results were that the those who wished to end their life before the disease took them had nothing to do “with gender, age, marital status, education, considering oneself as a religious person,” like one might assume (Booij et al., 2014). Since Huntington’s disease is autosomal dominant, the patient is most likely to have experienced some form of the disease early on. Baring witness to a family member going through the disease is the biggest impact on the patients decisions whether or not they seek out the option for euthanasia (Ekkel et al., 2022). This emphasizes the point that those who haven’t experienced the disease are not likely to understand the full gravity of the situation. It is easy to read lines on a paper and believe that, as a fellow human being, one can understand the impact the disease has, however as the study showed, the biggest impact to the patient decision was if they bared witness to the disease firsthand (Ekkel et al., 2022). In addition, this highlights the affect that the disease has not only on the patient but on their family members.

In setting parameters for those who are eligible to die with dignity, the Supreme Court stated that “the point at which the suffering becomes unbearable is a decision that only a patient can make,” alluding that patients must make their decision while of sound mind after physician review (Booij, Engberts, Tibben, et al., 2013). It is important to note that while Huntington’s patients make up an average of 16.5% of the euthanasia deaths compared to the general population, the suicide rates are higher than the general population (Booij, Engberts, Tibben, et al., 2013; Ekkel et al., 2022). When faced with limited options to end their suffering, patients are forced to find alternative means. A patient in an interview stated, “’You get a shot and you go. That doesn’t hurt. Instead of going over a bridge and throwing yourself off, or something.’”(Theriault et al., 2021). In the Netherlands, where euthanasia was legalized in 2002, there was an emphasis that the request is up to the patient who is well informed, and under the condition that their suffering is no longer bearable with no signs of improvement or alternative (Booij, Engberts, Tibben, et al., 2013). In another study, participants that requested euthanasia were asked at what point did they no longer want to live. The majority of patients were very vague on what made life worth living but were forthcoming on the conditions they no longer wanted to live with and included these conditions in their advance directives (Ekkel et al., 2022). The conditions, deemed what makes life worth living, were all related to losing their independence and dignity (Booij et al., 2014). Keeping in mind the stark difference between not wanting to choose euthanasia versus being denied the option on the basis of another’s opinion is a critical point to improving care for terminal patients.

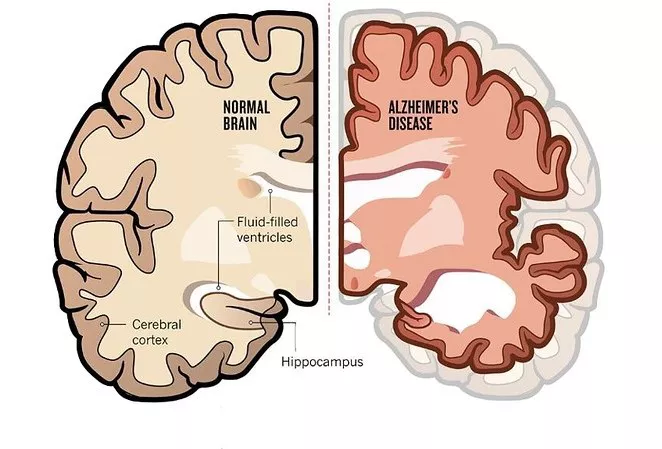

In the late stage of Huntington’s disease, patients experience cognitive decline very similar to Alzheimer’s patients. The progression in both diseases is a decline in cognitive abilities to the point in which individuals are unable to care for themselves. This progression is gradual, so that patients are aware of the changes they are going through, causing them to suffer mentally (Theriault et al., 2021). They are able to understand they are losing memories and the ability to perform normal everyday tasks (Braun et al., 2022). While most Alzheimer patients are aware of what is happening, there are extremes on both ends. Those who are untreated or undiagnosed may be more likely to experience anosognosia, the rejection of an issue or complete unawareness of loss of cognitive function. Hypernosognosia, the opposite is when an individual is hyper aware of the loss of function (Mondragon et al., 2019). Unlike Huntington’s disease there is no guaranteed biomarker for Alzheimer’s. There are several genetic tests that could indicate the disease, but have not been approved for general use (Braun et al., 2022).

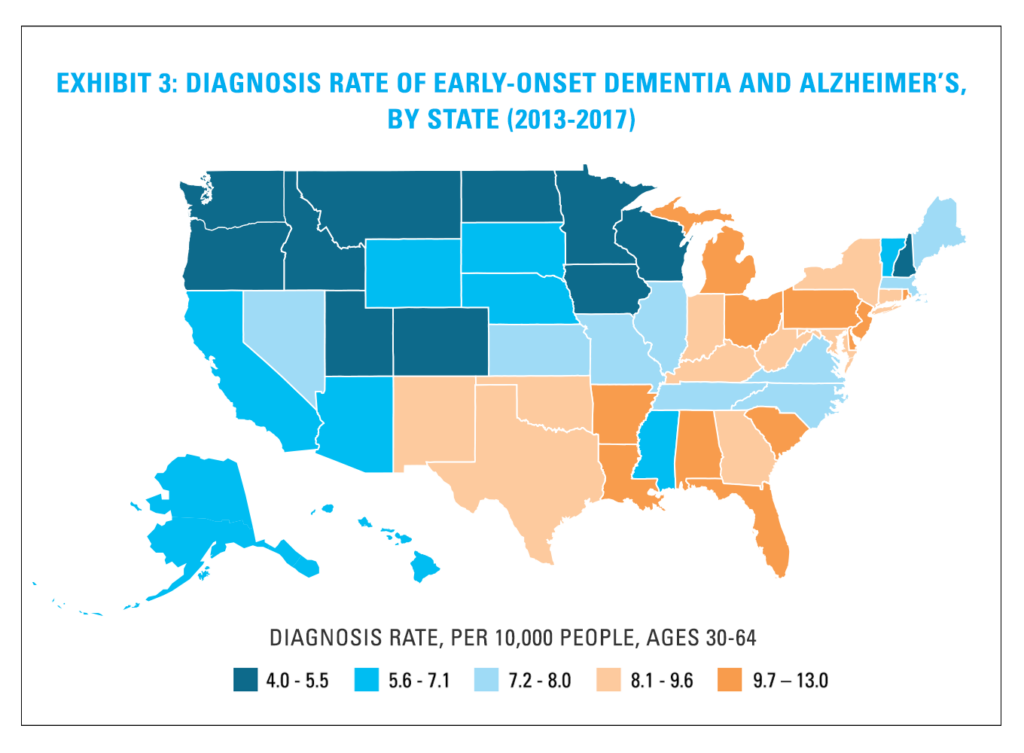

Treatment options for include memory inducing activities like, “art, dance and music therapy,” (Braun et al., 2022). Access to facilities that support those with Alzheimer’s are limited and costly and, as patients decline and are unable to work, they will have to rely on family for financial support. In tandem with providing patients with euthanasia as a treatment option, overall care should be evaluated to promote accessibility, especially as related to cost.“15 million Americans provide unpaid care for family members with AD or other dementias” and more than 50 million people across the world have Alzheimer’s, alluding to the financial barriers to quality care (Davis, 2018).

Everyday entertainment that we take for granted like following a plot in a series or movie can be lost to this disease (Davis, 2018). A study was performed on patients with Alzheimer’s in its early stages to get an idea of their thoughts and attitudes. To summarize the points of what the disease contains came down to loss of autonomy, cognitive impairment, suffering of loved ones, personal suffering, and social repercussions (Theriault et al., 2021). For those who want euthanasia, their reasons vary depending on their situation and protecting their wishes falls on the responsibility of those around them. Looking at countries that have legalized euthanasia and improving their system to ensure that those who are vulnerable are taken care of allows for an adaptive system.

Conflicts with the use of any form of euthanasia revolves around patient ability to understand and make decisions. Their competency to make a choice and their capacity to perform tasks have to be assessable to legal and medical professionals (Mondragon et al., 2019). Issues arise for those who are suffering from late stage Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s disease as they are no longer have the capacity to make decisions (White et al., 2022). This can be resolved by proactive and open discussions about advance directives to allow for the ability to make decisions while still cognizant. It can be argued that there may be conflict between the two versions of the person, one who wrote the advance directive and one who has no memory of the decision (Theriault et al., 2021). The loss of memory and changes in overall behavior are classic signs of the advance stages of these diseases and the pressure to abide by the advance directive falls on the physicians and the family members of the patient.

Personal bias can conflict with the advance directive. Even where it is legalized, there are few physicians that agree to respect advance directives that include euthanasia requests (Theriault et al., 2021). In a study involving Huntington’s patients, patients expressed the fear of following through with euthanasia is not due to the fear of dying, but because of the temptation to keep on living. There is a want to see their families, and they expressed the difficulties of keeping their own desires (Ekkel et al., 2022). For those who are seeking euthanasia, the option isn’t so cut and dry. The decision is a difficult one to make as the decisions not only affects them, but those around them. When they finally come to a decision, it should be honored and respected. Patients are aware of the basis around them and the fact their wishes may not be carried out.

Over 50% of physicians in the Netherlands refused to perform euthanasia on Alzheimer’s patients (Booij, Engberts, Tibben, et al., 2013), defeating the purpose behind the advance directive. Advance directives is a way to secure the wishes and autonomy of a patient when unable to make the decisions themselves (Davis, 2018). Refusing to honor advanced directives is a violation of trust. Open conversation should be had between the patient, their family members, and physicians to ensure that everyone is on the same page. It is the responsibility of the physician to provide all options and facilitate difficult conversations to ensure that the patient is well informed. If the physician does not agree with the patient stance, they should refer them to another physician (Booij, Engberts, Rödig, et al., 2013).

There are valid concerns about euthanasia from a religious and ethical standpoint. For Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s patients, these groups are especially vulnerable to external pressures. Measures should be taken to ensure that each patient has had proper care and is informed before making the decision. That doesn’t mean they should be barred from euthanasia as a treatment option or be unable to access care due to a overwheliming number of obstacles. Based on survey conducted, the result showed that the general population and physicians support euthanasia or similar treatments (Lindblad et al., 2010; Theriault et al., 2021; White et al., 2022). A quote for one of the studies from Alzheimer’s patient is as follows: “We worry about the effect of [our] life’s last stage on the character of [our] life as a whole, as we might worry about the effect of a play’s last scene or a poem’s last stanza on the entire creative work.”(Davis, 2018).” The road to accepting euthanasia is not an easy one, but remembering the goal of euthanasia is not quitting or giving up gives context as to why some patients would choose this treatment plan. It is to alleviate the suffering based on their own wishes expressed through advance directives with the help of medical and legal professionals. The freedom to choose does not make such a decision easy and that should be respected.

References

BERESTOVA, A. V., GORENKOV, R. V., ORLOV, S. A., & STAROSTIN, V. P. (2019). Ethics in medical decision making: An intercultural outlook. Utopia y Praxis Latinoamericana, 24, 144–151.

Booij, S. J., Engberts, D. P., Rödig, V., Tibben, A., & Roos, R. A. C. (2013). A plea for end-of-life discussions with patients suffering from Huntington’s disease: The role of the physician. Journal of Medical Ethics, 39(10), 621–624.

Booij, S. J., Engberts, D. P., Tibben, A., & Roos, R. A. C. (2013). Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in Huntington’s disease in The Netherlands. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(2), 339–340. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212001639

Booij, S. J., Tibben, A., Engberts, D. P., Marinus, J., & Roos, R. A. C. (2014). Thinking about the end of life: A common issue for patients with Huntington’s disease. Journal of Neurology, 261(11), 2184–2191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-014-7479-4

Braun, B., Demling, J., & Loew, T. H. (2022). Alzheimer’s disease: History, ethics and medical humanities in the context of assisted suicide. Philosophy, Ethics & Humanities in Medicine, 17(1), 1–7. Academic Search Complete. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13010-021-00111-z

Davis, D. S. (2018). Advance Directives and Alzheimer’s Disease. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 46(3), 744–748. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110518804235

Ekkel, M. R., Depla, M. F. I. A., Verschuur, E. M. L., Veenhuizen, R. B., Hertogh, C. M. P. M., & Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D. (2022). Patient perspectives on advance euthanasia directives in Huntington’s disease. A qualitative interview study. BMC Medical Ethics, 23(1), NA-NA. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-022-00838-0

Ferguson, M. W., Kennedy, C. J., Palpagama, T. H., Waldvogel, H. J., Faull, R. L. M., & Kwakowsky, A. (2022). Current and Possible Future Therapeutic Options for Huntington’s Disease. Journal of Central Nervous System Disease, 14, 11795735221092517. https://doi.org/10.1177/11795735221092517

First ever map published of global assisted dying laws. (n.d.). Humanists UK. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from https://humanists.uk/2021/07/19/new-research-maps-global-assisted-dying-laws-for-the-first-time/

HOA-Dementia.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved October 28, 2023, from https://www.bcbs.com/sites/default/files/file-attachments/health-of-america-report/HOA-Dementia.pdf

Lindblad, A., Juth, N., Fürst, C. J., & Lynöe, N. (2010). Continuous deep sedation, physician-assisted suicide, and euthanasia in Huntington’s disorder. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 16(11), 527–533. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.11.80019

Massage Therapy and Alzheimer’s Disease | Massage Therapy Journal. (n.d.). American Massage Therapy Association. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from https://www.amtamassage.org/publications/massage-therapy-journal/massage-and-alzheimers/

Mondragon, J. D., Salame, L., Kraus, A., & Deyn, P. P. D. (2019). Clinical Considerations in Physician-Assisted Death for Probable Alzheimer’s Disease: Decision-Making Capacity, Anosognosia, and Suffering. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 9(2), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500183

Portacolone, E., Covinsky, K. E., Johnson, J. K., Rubinstein, R. L., & Halpern, J. (2019). Walking the Tightrope between Study Participant Autonomy and Researcher Integrity: The Case Study of a Research Participant with Alzheimer’s Disease Pursuing Euthanasia in Switzerland. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 14(5), 483–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264619853198

The Signs and Symptoms of Huntington’s Disease. (n.d.). Verywell Health. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from https://www.verywellhealth.com/huntingtons-disease-symptoms-5091956

Theriault, V., Guay, D., & Bravo, G. (2021). Extending Medical Aid in Dying to Incompetent Patients: A Qualitative Descriptive Study of the Attitudes of People Living with Alzheimer’s Disease in Quebec. Canadian Journal of Bioethics (Revue Canadienne de BioéThique), 4(2), 69–78.

What is Alzheimer’s Disease? (n.d.). DoveMed. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from http://www.dovemed.com/health-topics/focused-health-topics/what-alzheimers-disease/

White, B. P., WILLMOTT, L., DEL VILLAR, K., HEWITT, J., CLOSE, E., GREAVES, L. L., CAMERON, J., & DOWNIE, R. M. J. (2022). WHO IS ELIGIBLE FOR VOLUNTARY ASSISTED DYING? NINE MEDICAL CONDITIONS ASSESSED AGAINST FIVE LEGAL FRAMEWORKS. University of New South Wales Law Journal, 45(1), 401–444.