According to author Charles MacCord, “The story of the ‘Monitor’s’ building has been often told: the fertility of invention, facility in designing, speed and accuracy in drawing, promptness in execution, and unwearied industry which made the construction possible in so short a time.”1 On September 11, 1861, the Swedish inventor’s idea of an Ironclad warship was presented to the Naval Board of Review. This committee comprised three Naval Officers—Joseph Smith, Hiram Paulding, and Charles H. Davis—all of whom were appointed by Congress to oversee the creation of the iron vessel, yet each was weary of the practicality of Ericsson’s creation. His first proposal was rejected, motivating Ericsson to travel to Washington and personally convince the board to approve his plan. On the morning of September 15, he arrived in Washington D.C., and gave a detailed account of why the government should choose his design. Ericsson spoke of the benefits that the Monitor provided and more importantly, he assured the board that he could have the vessel completed in a three-month period. Since the Confederate navy had already begun construction of their version of an ironclad warship at Gosport, his proposal was extremely attractive and gave the board no reason not to accept his proposal. Ericsson finished the meeting by demanding that it was the Naval Board of Review’s duty to sign off on Ericsson’s proposal. And eleven hours later his design was endorsed, and construction was to begin at once.

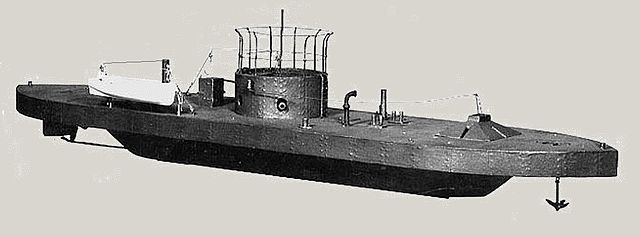

During the next three months of construction, there was an urgency to have this ship in the water. With the Confederates substantially ahead of the Union in the design process for an Ironclad warship, the proposal that Ericsson gave of a one-hundred-day approximation was appealing, provided that the ship actually worked. But in order to fulfill his promise, Ericsson was forced to make adjustments to his invention. For example, writer Stephen Thompson claims “Ericsson decided to change the turret armor to eight one-inch-thick layers, riveted and bolted together.”2 This saved time while also increasing the integrity of the armor. Additionally, Ericsson’s background in engineering allowed him to modify the overall size of his invention, once again speeding up the construction process. To the Union’s surprise, this revision provided unforeseen benefits, compared to the larger ironclad that the South was creating. Ultimately, Ericsson was fixing two problems with this modification. When looking at the design of the revised Monitor, it is substantially smaller and therefore had a smaller target area for a southern ship to inflict critical damage. Although Ericsson’s battle with time would not end until the battle of Hampton Roads, his ability to work on a tight schedule and make alterations aided the efficient construction of the USS Monitor.

This, however, was not a one-man feat. Writer William Roberts records that “Ericsson’s partners in the Monitor project were Bushnell, John F. Winslow, and John F. Griswold. In what Winslow later characterized as ‘a verbal agreement, and nothing more,’ Ericsson was to provide the engineering knowledge while the others provided the capital, and the four would split the profit or loss equally. Even more important than capital, Ericsson’s partners provided influence.”3 This meant that Ericsson could utilize his time to manage the engineering aspects of the ship while the other three could handle the financial and political side of the project. If not for the capital and influence that Ericsson’s three partners possessed, the construction of the Monitor would have taken far longer and would have had less of an impact on the Civil War and on the future of naval warfare. Specifically, Winslow and Griswold had connections with members of Congress. This critical relationship is a reason that the manufacturing of the Monitor operated smoothly. Ericsson’s three partners were in constant communication with the administration and were even close enough to where they had power over the Naval Board of Review. They were able to hire crew and choose where construction would take place without interference from their leaders. Basically, this partnership gave the four men influence over the government to have their visions seen through and a freedom for Ericsson to customize the Monitor however he saw fit.

The first key characteristic of the USS Monitor is that it was a departure from the use of wooden battleships. Author David Mindell describes that “Contemporary observers hailed the event as a revolution in technology, marking the end of wooden navies and the rise of superior steam-powered, armored fleets.”4 Accordingly, this gave the Union a level playing field against the Southern naval powerhouse. It was obvious that a boat lined with iron armor and a protective metal shell was superior to a vessel entirely comprised of wood. But Ericsson’s implementation of this feature is the reason the USS Monitor became so successful. Ericsson’s design called for a great deal of metal materials. His invention called for giant metal plates that made up the hull of the ship, but each piece weighed a minimum of six hundred pounds apiece. Also, the Monitor needed metal turrets and belt armor plates that measured out to over one thousand pounds. The great deal of metal made the Monitor hefty but very secure. Ericsson’s mission then became engineering a way for the ship to float but also maintain maneuverability. At this point in construction, it was going to be unrealistic to match the size of the Ironclads that the South had built several months before. So, Ericsson made the decision to decrease the size of the ship but still utilize the iron design. This proved to be beneficial because the reduced length provided the ship with the ability to maneuver the water more easily than its wooden predecessor and even allowed for an added layer of safety to the crew. The ironclad provided so much support that some of the crew aboard the Monitor complained that they were too protected. They saw no way for them to be a hero when they were enclosed inside an impenetrable war machine. One sailor in particular, Frederick Keeler, named the Monitor an “Iron Shield” that every member aboard had confidence they were protected. This feeling, shared by countless others of the sailors on board was not a bad thing though. The feeling of invincibility is what Ericsson provided the Monitor. He constructed it so that it would be small and mobile enough to avoid enemy fire, but if needed, strong enough to withstand being hit and damaged.

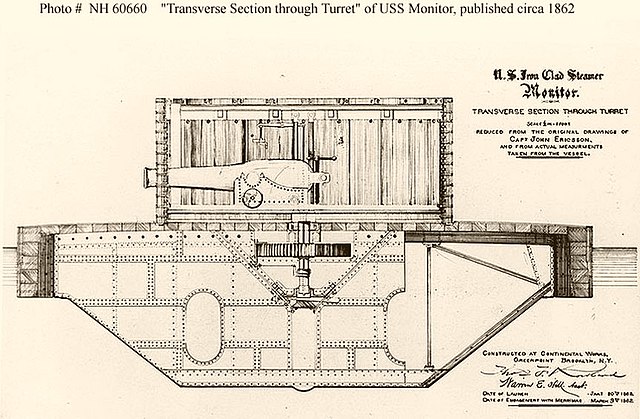

The Monitor was not solely assembled to withstand damage though. It was created to efficiently attack and wear down opposing ships. Stephen Thompson affirms that this was facilitated by the addition of “two standard length XI-inch Dahlgrens from the Dacotah. The guns, numbers 27 and 28.”5 These two turrets allowed for a more precise attack on the enemy. Instead of the ship having to completely turn so that a cannon was in a position to hit the enemy, the innovative implementation of the turret made it so that a man within the Monitor could aim the weapon, and the ship could continue on the most advantageous path for itself. This was made possible because the power to reverse the rotation of the turret was not excessive. It could smoothly be aimed in any direction needed. The weight of the gun also made it so that the stability of the weapon would make staying on a target easier. Even though it was extremely heavy, the turret provided the Monitor the ability to inflict damage at a faster and more precise rate than any other vessel. Although the South’s CSS Virginia had fourteen cannons aboard, Ericsson’s turrets gave the North a superior advantage when it came to the quality of damage imposed. Additionally, being manned by two crew members allowed for them to isolate their efforts on marking the enemy ship and firing shots until the stability of the other boat was destroyed. Not only was the turret itself powerful, but it was protected by an eight-inch armored plate. It was also in a rounded shape so any shot that would hit it would be deflected and not damage the turret. This converted the Monitor into a virtually impossible-to-disable machine of war. This feature was unlike any type of weapon that had been put onto a floating machine before. Ericsson’s ability to incorporate a rotating and impenetrable turret gave an advantage to the Union and is even referred to as the Monitor’s most beneficial contribution to naval architecture.

There were still problems with the manufacturing of the ship though. Getting the ship complete in such a sharp deadline meant making continuous changes and modifications that Ericsson did not account for. One giant fault was the inability of parts of the ship to communicate with one another. Stephen Thompson demonstrates that “Orders and observations were shouted down to one of the waiting officers who would then run to the opposite end and relay the message by shouting it back.”6 This gave rise to the possibility of an inability to execute orders by the captain efficiently and in a quick manner. Ericsson could not really do anything to fix that problem though. There were bigger and more pressing matters that required Ericsson to hone his focus. For one, the Monitor was part submarine so this created problems in how to keep fifty men below deck alive and safe. To fix this problem Ericsson implemented a complex ventilation system that gave the men on board a way to breathe. Since the Monitor was completely enclosed, this feature also kept the cabin safe because it was now at a normal atmospheric temperature. But the biggest problem was going from concept to reality aboard the boat. Ericsson was treading in uncharted territory and the new technology that was required to submerge the crew was not tested in battle yet. This was immediately questioned by the Naval Board of Review; due to their old-style views, they were extremely skeptical of putting their crew in such a vulnerable position. The board was even hasty to incorporate a steam engine because it was new and had no precedence. But Ericsson, having decades worth of experience in mechanical engineering, was able to convince them to approve his decision. His sanguine personality and problem-solver mindset allowed him to present all of the possible benefits that came with submerging the crew. A problem that would have destroyed other engineers was simply a way for Ericsson to make the Monitor better, and that was made official when the USS Monitor first met water.

On January 20, 1862, time was up for the creation of the Monitor. The seemingly unrealistic one-hundred-day limit had come, but all that was missing was a couple of iron plates. The launch of the Monitor was only delayed by a couple of days. This meant that Ericsson’s team had the ability to make last-minute improvements. One modification was the removal of the pilot house’s armored roof. This allowed the men controlling the turrets a clearer view and a better-aiming mechanism, which improved the Monitor’s capability for attack. And with that final touch, Ericsson’s Monitor was ready to be put into the water. So according to Stephen Thompson, “the Monitor was launched exactly on schedule, at 10:00 A.M., Thursday, January 30, 1862, just ten minutes after the final armor plate had been attached, with Ericsson standing defiantly upon her.”7 This event produced a ton of fanfare around it. Hundreds of people gathered in Brooklyn, New York to witness history taking place. Ericsson’s boat was mesmerizing to most of the people who were viewing his technology for the first time. A ship that was entirely constructed of metal, had no masts or sails, and had parts fully submerged in water was unimaginable to most citizens. Besides a few small issues, such as the anchor being unable to be weighed and a blower engine being shut down because a valve came off, the boat was ready to be commissioned and put to the test. On February 25, 1862, the USS Monitor was commissioned with Lt. John L. Warden in command. But to Ericsson’s dismay, as the pilot was leaving the harbor, he noticed that there was a problem with the steering. While the Navy Department was in favor of an entirely new rudder being added, Ericsson created a new method that would double the power of the wheel. He added a set of pulleys to the wheel and that made the steering smoother and more accurate. This ultimately saved days of work compared to what the Navy Board had suggested, and even ended up increasing the mobility and functionality of the warship. With the Monitor in the water, it now had to prove that it could withstand battle. So, the Monitor was ordered to sail to Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the infamous CSS Virginia was waiting for them.

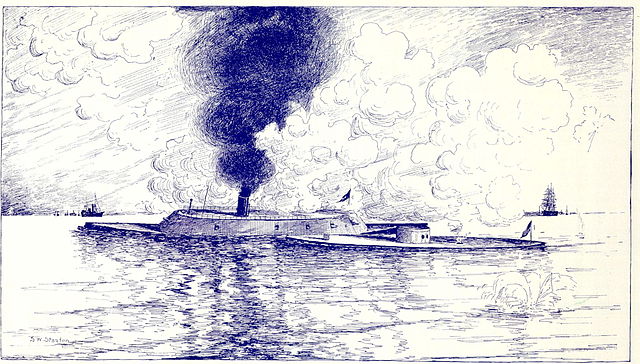

On the morning of March 8, 1862, the Battle of Hampton Roads marked the first battle of Ironclad warships against each other. Author David Mindell emphasized that “The Southern Virginia was a steam frigate whose standard wooden structure was literally clad with iron. The Northern Monitor, in contrast, represented a more radical innovation; though called an ‘ironclad,’ it was designed from the first as an iron ship and incorporated numerous new mechanisms. More than its opponent, the Monitor thus elicited broad and complex reactions to the changes it seemed to foreshadow, both for the future of technological warfare and for the human encounter with technology.”8 The battle itself lasted no more than four hours, but it was the strategic maneuvers of the Union that made it such a remarkable encounter. The CSS Virginia had been terrorizing the Union’s wooden ships for two months since it was commissioned. There was no competition until the Monitor was created. The Monitor used its sleek design and mobile frame to outsmart and wear down the Virgnia. It was said at the beginning of the battle that the two ships circled and attacked each other as fast as they could. But neither of the ships was making a big enough impact to sink the other ship. But the Monitor definitely had the capability to do so if they had used heavier powder for the turrets. By hour 3 though, the Virginia had started to show signs of critical damage. This battle honestly proved the strength that the Monitor possessed. By the end of the interaction, the Virginia had been a couple of shots away from being sunk to the bottom of the river. However, the battle ended up in a stalemate, with both sides of the fight claiming victory. But it is the USS Monitor that gets credit for changing the course of Naval warfare. The Monitor gets this credit because in relation to the other ship, it was far less damaged. Being able to withstand the attack of the Confederate ship and not be blown away would have been victory enough. But actually, damaging the CSS Virginia and forcing it to be decommissioned weeks later is what made the Monitor so special. Ericsson’s radical invention, with the dozens of modifications and adjustments he had created, actually worked and gave the union the ability to control the water. Mindell writes, “The crew of the Monitor enjoyed the full glory of warfare, gaining public attention and commendation for their brief action. But the very forces of perception that drove its creation neutralized the technology designed to contain and protect its inhabitants. This was the paradox of the war machine. Public imperatives of developing, selling, and deploying a complex technology gave new life to the heroic aspect of war by promoting the Monitor and its crew, even as the technology reduced their status from warriors to operatives.”9 The Union’s victory at Hampton Roads even allowed them to keep their blockade of Southern ports, making it increasingly harder for the South to transport supplies by river and led to the overall victory of the Union in the Civil War.

With the victory of the Monitor at the battle of Hampton Roads, Ericsson’s Monitor was now proven and successful. His invention had shocked the entire Confederate fleet and catapulted the United States Navy into a world power. Having the ability to produce more damage and avoid being destroyed is what made his technology so important for the coming years of naval warfare. After the Monitor beat the CSS Virginia, William Roberts recounts that “Welles was finally free to accelerate ironclad procurement. Monitor’s success, Fox’s ‘monitor mania,’ and Welles’s sense of urgency combined to ensure that contracts for more ironclads were let as soon after Hampton Roads as possible.”10 By the end of the Civil War, the union had at least sixteen fully functional Ironclads ready for engagement. This made the Ironclad a main part of the Navy and the new normal for a warship. By incorporating iron with revolving weaponry, ships would be more lethal and be able to stay above water for longer. Ericsson’s ability to problem solve, meet deadlines, and use his engineering prowess to construct the innovative new ship is what has made him an icon in U.S. history. MacCord summarized that achievement: “In a word, he had done more to develop this country than he did even to defend it. Either was a more than sufficient foundation for enduring fame, but with the latter his name will be always more closely associated by every true American; and simply as the builder of the “Monitor.”11 The Monitor had transformed Ericsson into a true American hero.

- Charles W. MacCord, “Ericsson and His ‘Monitor,’” The North American Review 149, no. 395 (1889): 461. ↵

- Stephen C. Thompson, “The Design and Construction of ‘USS Monitor,’” Warship International 27, no. 3 (1990): 220. ↵

- William H. Roberts, “‘The Name of Ericsson’: Political Engineering in the Union Ironclad Program, 1861-1863,” The Journal of Military History 63, no. 4 (1999): 830. ↵

- David A. Mindell, “‘The Clangor of That Blacksmith’s Fray’: Technology, War, and Experience Aboard the USS Monitor,” Technology and Culture 36, no. 2 (1995): 242. ↵

- Stephen C. Thompson, “The Design and Construction of ‘USS Monitor,’” Warship International 27, no. 3 (1990): 226. ↵

- Stephen C. Thompson, “The Design and Construction of ‘USS Monitor,’” Warship International 27, no. 3 (1990): 227. ↵

- Stephen C. Thompson, “The Design and Construction of ‘USS Monitor,’” Warship International 27, no. 3 (1990): 237. ↵

- David A. Mindell, “‘The Clangor of That Blacksmith’s Fray’: Technology, War, and Experience Aboard the USS Monitor,” Technology and Culture 36, no. 2 (1995): 242. ↵

- David A. Mindell, “‘The Clangor of That Blacksmith’s Fray’: Technology, War, and Experience Aboard the USS Monitor,” Technology and Culture 36, no. 2 (1995): 268. ↵

- William H. Roberts, “‘The Name of Ericsson’: Political Engineering in the Union Ironclad Program, 1861-1863,” The Journal of Military History 63, no. 4 (1999): 843. ↵

- Charles W. MacCord, “Ericsson and His ‘Monitor,’” The North American Review 149, no. 395 (1889): 471. ↵

1 comment

Eduardo Saucedo Moreno

Hello Brennan, I found your article very interesting. The first time I heard of the USS Monitor was at a museum in New York years ago, I just never go the chance tolerant more about it. In my opinion, this article really educated me in a very simple and clear way. Moreover, It was very easy to understand and I also liked the images that you chose to incorporate into your article. Good job!