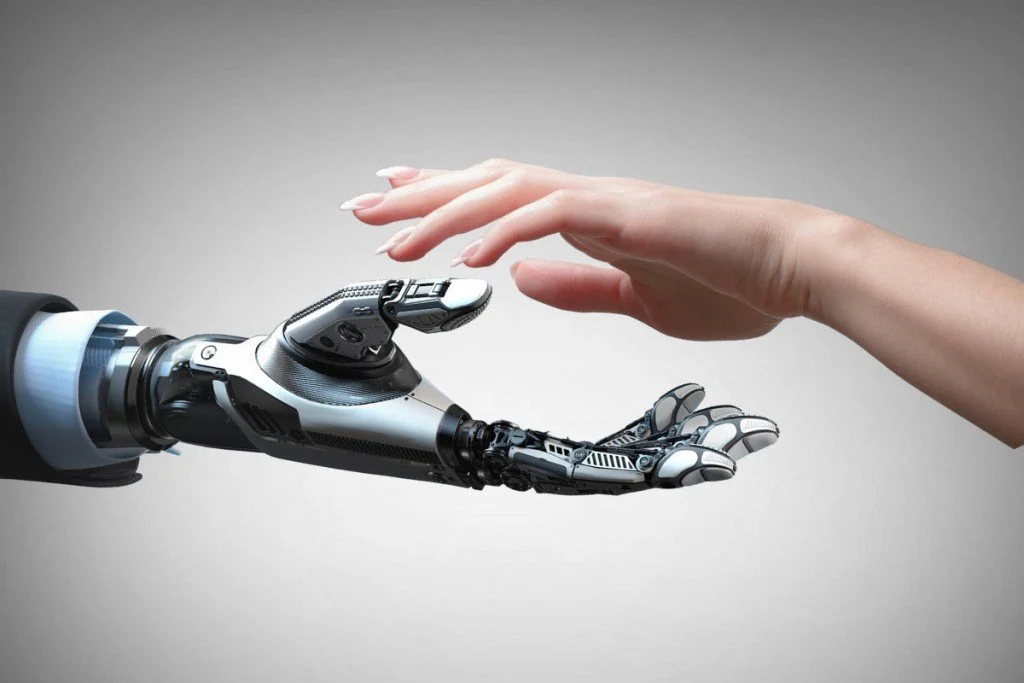

The history of prosthetics is a tribute to human creativity and the never-ending quest to improve the quality of life for individuals with limb disabilities, starting with the earliest known wooden toe prosthesis worn by an Egyptian mummy and continuing to the the most advanced bionic limbs of today.1

Creating prostheses that are customized to each person’s specific needs is a difficult and time-consuming process that demands exacting attention to detail. Initially, the prosthetist works closely with the patient to collect precise measures, sometimes even before the amputation of a leg. If possible, the prosthetist also consults with the surgeon to gain further insight into the impending amputation. Following surgery, the prosthetist and surgeon collaborate to decide the best dressing for the patient, which usually involves wearing a compressive garment to speed up the healing process.2

The prosthetist takes a fiberglass cast or plaster mold of the limb once the patient has healed and any remaining swelling has decreased. Using a mixture of plaster, water, and vermiculite (a material used as a plaster filler to lessen the weight of larger casts), this hollow cast is turned into a replica of the patient’s leg. The rigorous process of modifying the mold starts, adding imagined designs to make a wearable prototype. A transparent plastic model of the limb is made in order to guarantee the best possible fit in the beginning. After it fits perfectly, the plastic socket develops into a stronger version that becomes the artificial limb’s base. This more durable version is usually made of carbon fiber or acrylic laminate. During this complex production process, the prosthetist pays close attention to the patient’s bones, muscles, tendons, and general health. Above all, the prosthetic needs to be designed to let the patient perform daily activities with ease, such as jogging and walking, as well as tasks like picking up a phone or opening doors.3

Before diving into the story I’m about to share, let me introduce the individual who generously shared his story with me and provided invaluable assistance for this article. Dr. Gary Guerra, currently serving as Assistant Professor in the Department of Exercise and Sports Science at St. Mary’s University, has a rich professional background. Formerly associated with the Sirindhorn School of Prosthetics and Orthotics at the Faculty of Medicine, as well as Siriraj Hospital at Mahidol University in Thailand, Dr. Guerra earned his Ph.D. in Rehabilitation Science from Loma Linda University in 2017. Additionally, he holds a Master’s and Bachelor’s of Science in Kinesiology from Texas A&M San Antonio and a postgraduate certificate in prosthetics from the Orthotics and Prosthetics Program at California State University, Dominguez Hills. Dr. Guerra’s dedication extends beyond his academic pursuits; he has played a crucial role in training prosthetic and orthotic clinicians across various countries, including Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Vietnam, Indonesia, Nepal, Japan, Rwanda, Tanzania, Togo, Sudan, Libya, and Palestine. Notably, Thailand, the setting of the upcoming story, is among the places where Dr. Guerra has made significant contributions.4

This story unfolds in the vibrant city of Bangkok, Thailand, in the year 2017, within the halls of Siriraj Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Mahidol University. It is here that Dr. Guerra’s path crossed with a man in dire need of profound assistance. This individual, later revealed to be named Somjit, had been enlisted as a patient model in the prosthetics program. As Dr. Guerra delved into Somjit’s story, he uncovered a tale marked by unfortunate circumstances. Somjit recounted a moment when he faced electrical issues and, in an attempt to resolve them independently, found himself in an unfortunate situation resulting in electrocution. The aftermath was nothing short of devastating—Somjit underwent the amputation of all four limbs, losing both arms and legs. This life-altering event prompted him to seek not only a place willing to assist in rebuilding his life, but also it left him grappling with unemployment. The encounter with Somjit laid the groundwork for a transformative journey of undergoing the resilience needed to overcome profound adversity.5

Somjit’s previous occupation demanded long hours on his feet, with constant use of his hands. Compounding the challenge, the streets in Thailand, where he resided, were far from smooth, often presenting uneven terrain. Despite these obstacles, Somjit embraced his role as a patient model, generously offering his body as a canvas for students to meticulously create casts of his residual limbs, laying the foundation for the development of tailor-made prosthetics. Working alongside Dr. Guerra, a collaborative effort unfolded with a team of dedicated graduate students. Together, they went on the intricate journey of crafting these prostheses designed specifically for Somjit. This intricate process demanded a substantial investment of time and energy from all parties involved, Dr. Guerra, the graduate students, and, notably, Somjit himself. Their joint commitment to precision and excellence highlighted the seriousness of this task, and focused attention on the dedication required to ensure the creation of prosthetics that would significantly enhance Somjit’s quality of life.6

After navigating through a series of challenges and triumphs, Dr. Guerra and the dedicated team of graduate students successfully crafted prostheses tailored to Somjit’s unique needs. These prostheses not only fit him but also provided him the comfort and mobility essential for his daily activities. Designed with meticulous attention to detail, these prosthetics seamlessly integrated into Somjit’s life, aiming to restore not only his job but also his independence. Following the meticulous creation of the prostheses, Dr. Guerra and the graduate students initiated a series of tests to ensure their suitability for Somjit’s dynamic lifestyle. In one trial, they tasked him with delicately picking up small cubes and transferring them to another box with precision, all while being timed. The results of this test served as a gauge for the efficacy of the prostheses. Another evaluative measure involved Somjit picking up a small medicine ball and launching it as far as possible. Once again, the team scrutinized the outcomes, determining the compatibility of these specific prostheses with his daily routines and activities. Through these rigorous tests, the collaborative effort of Dr. Guerra and the graduate students has not only yielded functional prostheses but has paved the way for Somjit to reclaim a sense of normalcy and autonomy in his life.7

So, the final prosthesis was designed to understand which prosthetic feet and hands were most functional for this very unique type of patient. Somjit required feet that could be more responsive to his walking on uneven terrain during his work in Thailand. As I mentioned, the roads of Thailand are uneven, and unfortunately, amputees lose the muscles below the knee and the Achilles tendon. Thus, the amputee requires technology that can ‘mimic’ the function of the Achilles tendon and ankle flexors. So Dr. Guerra and his students created prosthetic legs that utilized carbon fiber, which stores energy like a spring, to help reduce the energy required to walk but also improve the ability to walk on uneven terrain. These improvements are very specific to Somjit’s life, which is why creating prostheses is so meticulous and can take numerous amounts of prototypes until you find the right one. Because of this slow and rigorous process, it took Dr. Guerra and the graduate students quite some time to create the prosthesis.8

The transformative impact of prosthetics is clearly evident in Somjit’s extraordinary journey. In a world without these remarkable technological advancements as well as the physical therapists who serve a just as important role after the prosthesis are fitted, some might argue that Somjit’s life would have faced some impossible challenges—his existence essentially halted without arms and legs, making him unable to care for himself or fulfill his daily needs. However, with the compassionate guidance of Dr. Guerra and the persistent dedication of the graduate students, Somjit not only regained control over his life but embarked on a gradual return to the familiar rhythms of his pre-accident life. This story serves as a powerful example of the life-changing capabilities of prosthetics, providing individuals like Somjit with the hope and opportunity to rebuild their lives. The integration of custom prosthetics allowed him to transcend the limitations imposed by the loss of limbs, empowering him to navigate the complexities of daily life and find renewed independence. The extraordinary resilience demonstrated by Somjit mirrors the immense potential that prosthetic technology holds in restoring both physical abilities and the sense of self. Moreover, as technology advances at an extraordinary pace, the landscape of prosthetics continues to evolve. This evolution not only promises greater advancements in design and functionality but also opens doors to improved life-changing possibilities for individuals facing similar challenges. The ongoing commitment to innovation in prosthetics underscores a future where the boundaries of possibility are continually pushed, offering a beacon of hope for those in need of transformative solutions.9

- Liz Swain and David E. Newton, EdD, “Prosthetics,” in The Gale Encyclopedia of Nursing and Allied Health, 4th ed., edited by Jacqueline L. Longe, 2967-2971. Vol. 5. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2018. Gale eBooks (accessed November 28, 2023). ↵

- Liz, Swain and David E. Newton, EdD, “Prosthetics.” in The Gale Encyclopedia of Nursing and Allied Health, 4th ed., edited by Jacqueline L. Longe, 2967-2971. Vol. 5. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2018. Gale eBooks (accessed November 30, 2023). ↵

- Gary Guerra, interview by Lilliana Cantu, St. Mary’s University, September 20, 2023. ↵

- Gary Guerra, interview by Lilliana Cantu, St. Mary’s University, September 20, 2023. ↵

- Gary Guerra, interview by Lilliana Cantu, St. Mary’s University, September 20, 2023. ↵

- Gary Guerra, interview by Lilliana Cantu, St. Mary’s University, September 22, 2023. ↵

- Gary Guerra, interview by Lilliana Cantu, St. Mary’s University, September 22, 2023. ↵

- Gary Guerra, interview by Lilliana Cantu, St. Mary’s University, September 22, 2023. ↵

- Robert Gailey, Ignacio Gaunaurd, Michele Raya, Neva Kirk-Sanchez, Luz M Prieto-Sanchez, Kathryn Roach, “Effectiveness of an Evidence-Based Amputee Rehabilitation Program: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial,” Physical Therapy, January 17, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31951260/. ↵