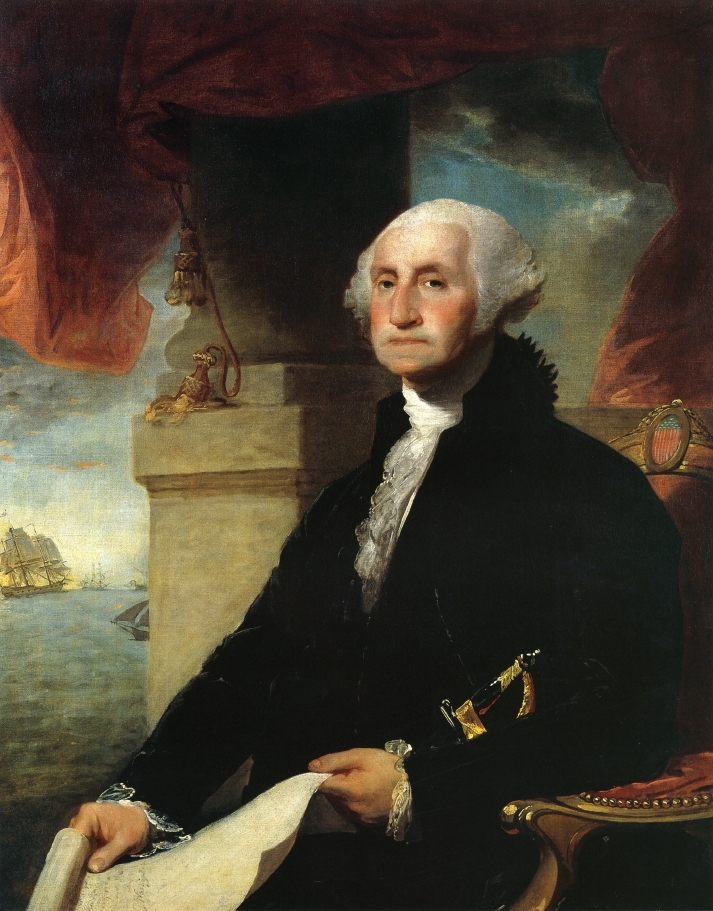

“I feel my self going. I thank you for your attention. You had better not take any more trouble about me; but let me go off quietly; I cannot last long.”1 These were George Washington’s dying words. Who could have imagined that this great Revolutionary War hero and first President could fall two years after his retirement? He seemed to be immortal in the public’s eyes. Staying in the spotlight for nearly twenty five years, standing as the symbol of American nationhood, he not only had stood as a symbol of America, but he had also commanded the armies that helped gain national independence. After all the wars, he never appeared fazed, never showed any type of weakness or vulnerability, until that frigid winter of 1799.2

The century was nearly over, and the future of the young nation seemed bright. The former commander-in-chief of the nation had retired to his estate of Mount Vernon and had set out on horseback to check on certain areas of his plantation. It was December 12, 1799.3 He was exposed to cold rain and snow, but that did not stop this man from carrying out his responsibilities. However, sometimes carrying out responsibilities can have serious consequences. The next day he woke early in the morning, having difficulty breathing. Later in the morning he started to developed pain in the throat, and this led him to be unable to swallow or speak well. He grasped for some air, constantly tossing and turning to find a comfortable position.4 Lying down in agony, he was surrounded by three physicians who were all at a loss as to what to do.

James Craik, Gustavus Richard Brown, and Elisha Cullen Dick were the attending physicians for Washington, and all knew him very well.5 The first to arrive was Dr. Craik on Friday, December 13, when Washington started first experiencing a cold with a light hoarseness. By 2 a.m. the next morning, he awoke with troubled breathing. At 6 a.m. he was showing signs of a fever with throat pain and respiratory suffering.6 Washington was unable to swallow and even had difficulty speaking. Dr. Craik believed that the only option for Washington was for a bloodletting.

Bloodletting is the surgical removal of blood from a patient, and it was a typical procedure physicians used in the eighteenth century. Typically, the physicians were not the ones that would carry out the bloodletting; they would call in a skilled bloodletter. In this case, the bloodletter was George Rawlins. At 7:30 a.m., Rawlins removed about 12 to 14 ounces of Washington’s blood. Washington actually requested an additional bloodletting. Two hours later, Dr. Craik applied a blister of cantharides to Washington’s throat and removed roughly 18 more ounces of blood. This was also done at 11 a.m.7 Washington was still alert at this time. He even had the strength to stand up and walk to the bathroom, but he still had trouble swallowing tea, nearly suffocating from the attempt and unable to cough up the fluid.

There was an argument among the physicians caring for Washington, whether there should be a fourth bloodletting. Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick believed that more bloodletting would make Washington’s condition worse. Nevertheless, Dr. Craik ordered for the bloodletting at 3 p.m.8 After the fourth bloodletting, Washington seemed to show improvement; he was able to swallow. With renewed strength, Washington was able to revise his will. He knew his time was coming to an end. As the night continued, his condition steadily worsened. The physicians tried their best to keep him stable by applying blisters of cantharides to his arms, legs, and feet. They even applied wheat-bran cataplasms to his throat.9 This did stop his condition from worsening.

At 10 p.m., Washington whispered his burial instructions to his aide. Twenty minutes later, George Washington died. The news of his death spread rapidly across the country. The grieving was not only at his at burial site, but across the Atlantic. There was a London newspaper that eulogized: “His fame, bounded by no country, will be confined to no age.”10 Units of the British fleet that was blockading a harbor in France dropped their ensigns to half-mast. Napoleon ordered a ten-day requiem.11 In the United States, newspapers would publish poems from grieving women. People traveled to Mount Vernon to pay their respects. Citizens dressed in black clothing for months.12

December 26 was the official day of mourning. At dawn, there were sixteen cannons that were fired, and they continued to boom every half hour until 11 a.m. After the firing of the cannons, there was a march of troops to the Lutheran Church where Henry Lee gave a memorial of Washington that became immortal: “First in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen, he was second to none in the humble endearing scenes of private life…The purity of his private character gave effulgence to his public virtues.”13 To pay tribute to the first president, Congress voted to construct a marble monument in the Capital building, which was still under construction in Washington, D.C. at the time. This was an appropriate tribute to a great man, and he will forever be immortal in our nation’s history.

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “George Washington’s Death.” ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, January 2015, s.v. “George Washington,” by David Curtis Skaggs. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “George Washington’s Death.” ↵

- David M. Morens, “Death of a President,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 341, (December 1999): 1845. ↵

- David M. Morens, “Death of a President,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 341, (December 1999): 1845-1849. ↵

- David M. Morens, “Death of a President,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 341, (December 1999): 1845. ↵

- David M. Morens, “Death of a President,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 341, (December 1999): 1845. ↵

- David M. Morens, “Death of a President,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 341, (December 1999): 1845. ↵

- David M. Morens, “Death of a President,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 341, (December 1999): 1846. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “George Washington’s Death.” ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “George Washington’s Death.” ↵

- David M. Morens, “Death of a President,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 341, (December 1999): 1846. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “George Washington’s Death.” ↵

73 comments

Aimee Trevino

Wow, really great article! George Washington is one of the most talked about figures in American history, so it is amazing and unusual that I have never even heard of his death! It is impressive to see that even under the circumstances, he carried out his responsibilities, and kept up his duties to our country. I believe it is amazing that he was able to do all this, and that he represented the country even while on his death bed. He definitely deserves all the tribute to his memory.

Gabriela Medrano

I am glad you explained what bloodletting is because I had no idea it was used in the eighteenth century. Also, what a slow painful death for one of America’s greatest heroes. I thought it was strange how he made a recovery and then worsened, false hopes. This incident was not only a nationwide tragedy but affected other countries as well, I found that very honoring. Good article and nice job!

Briana Bustamante

What a great article! I did not known about how George Washington died, nor did I know that he had made such a huge impact not only in the United States, but also around the world. I also did not know anything about blootletting, and how helpful it can be to a patient. I wonder what type of medicine they had back then? You told a great story, and I was able to have a visual in my head of George Washington’s journey home. Over all, nice work!!