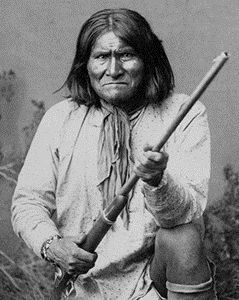

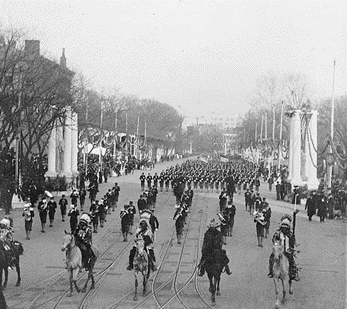

An inauguration parade is a vibrant and lively celebration that marks the beginning of a new era of a Presidency. People of all ages and backgrounds line the streets of Washington DC in hopes of seeing a procession of bands, military officials, and the President himself. It is a spectacle that fills the streets with cheers and excitement as it marks a new beginning. However, the 1905 inauguration parade of Theodore Roosevelt was anything but a celebration for Native Americans. This parade marked the end of a way of life as they knew it. With six Native Chiefs at the front of the parade, they were marched around the streets of Washington DC while onlookers stared with shock. All six of them wore large, colorful traditional headpieces and clothing while being led by the most hated native at the time, Geronimo. Among the crowd of onlookers, the President was seen cheering and clapping at the sight of the six chiefs. Woodworth Clum, who was the son of the Arizona reservation official, asked Roosevelt, “Why did you select Geronimo to march in your parade, Mr. President?” To which the president replied, “He is the greatest single-handed murderer in American History. I wanted to give the people a good show.”1

After years of raiding and attacking Mexican soldiers and people of Mexico and Arizona, Geronimo was sent to an Apache reservation in Sierra Madre in 1876. He had escaped the reservation three times, which allowed him to execute all forms of raids and acquire a record of brutality unlike any other native in his time. He was looked up to by his own tribe, the Chiricahua Apache, as they viewed him as possessing great power. This power also included a high achievement as a shaman with healing qualities. Despite this, Geronimo was not a chief during this time, as only thirty Apache would consider him as their leader. While he was not a true chief, he was looked up to as a leader of raids and war. One illustration of Geronimo’s leadership abilities was during an ambush in Chihuahua. Juan Mata Ortiz had slaughtered a group of Apache people who had been sent to negotiate. This act in Apache culture calls for revenge. On November 14, 1882, Geronimo and a fellow leader, Juh, led a group of 130 fighting men from the reservation to Chihuahua and backed the group of twenty-two citizens following Ortiz against a cliff and attacked them. After heavy fire and an overwhelming amount of hand-to-hand combat, all but Ortiz himself and one other lived. As they galloped away on a horse, Geronimo ordered they be let go, as Ortiz would bring more Mexicans back to be slaughtered.2

Geronimo led his last raid into Arizona on April 27, 1886, leading a band of raiders into the Hell’s Gate Canyon where they found a ranch house. One man climbed over a fence, which alarmed the dog, and after hearing the barking and growling of the dog, a young woman came out to investigate. She caught a glimpse of Geronimo and his band of raiders and then ran back into the house. A woman holding a baby frantically came outside. An Apache shot the woman, picked up her baby from the floor and then bashed the head of the baby against the adobe wall. About fifteen raiders went into the home and began ransacking the place when they saw the young woman. Geronimo decided to take her as a captive. Outside, there were two men working with cattle in the fields when they heard the shots. They mounted their horses and began to flee as Apaches rode after them. One man was shot and killed while the other’s horse was shot and went down. The Apaches stripped the man of his clothing and beat him with the backs of their rifles before taking him to Geronimo. The man who survived was Artisan Peck, who was spared by Geronimo for an unknown reason. Geronimo led the raiders away with the young girl, who was Peck’s niece. As Peck walked back to his home, he saw the horrors of what the Apache had done to his wife, child, and home. After this horrific event, the US calvary began to follow Geronimo. This raid was only one of hundreds of raids led by Geronimo and his followers against Americans and Mexicans. For over thirty years, Geronimo continued his reign of war and raids until it ultimately came to an end in 1886.3

After years of running from the United States military and other officials, a group of Chiricahua Apache warriors (including Geronimo) gathered in Skelton Canyon, Arizona on September 2, 1886. They had planned to finally stop running and formally surrender to General Nelson Appleton Miles. This same group of people had claimed they were going to surrender previously in March, but backed out of the surrender due to rumors that they were going to be hung for their crimes. They were chased by Miles for over four months, and with the help of two Chiricahua Apache scouts, Katiyah and Martine, and of Captain Henry Ware Lawton, they were able to locate the Chiricahua camp set up in the Sierra Madre. Along with Mile’s group, W.T. Melton and J.D. Prewitt prepared in the canyon to arrest the Apaches. Astonishingly, as the group was talking, Geronimo approached them on a horse and began to question Lawton. After receiving some answers, Geronimo left. Shocked by the interaction, Melton and Prewitt rode after Geronimo, and, after following him for half a mile, Geronimo turned around, saluted the two men and said “Adios, Seniors!” He then rode off alone back to the tribe, while Melton and Prewitt rode back to their camp. 4

Late in the afternoon on September 3, 1886, General Miles finally made it to Lawton’s camp. Once Geronimo realized Miles had arrived, he rode to their camp, got off of his horse, and shook Miles’s hand. They began discussing the terms of their surrender, and after a short discussion, Geronimo agreed to a peaceful surrender. However, Miles knew that Geronimo was not technically chief and could not formally agree to a surrender for the tribe. A man named Naiche was the formal Chief of the Chiricahua’s, and if he did not agree to the terms made by Geronimo, there would be no surrender. The next day, on September 4, First Lt. Charles B. Gatewood, Geronimo, and an interpreter rode back to the Chiricahua camp to talk with Naiche. He was hesitant in meeting with Miles, but after Gatewood explained that it would be rude to prolong the discussion, Naiche agreed to meet. They rode back to the camp, and Miles explained the surrender terms to Naiche. At last, Naiche, the last hereditary chief of the Chiricahua Apache, agreed to surrender. While many think September 4, 1886, marks the surrender of “Geronimo’s Band,” it was actually Naiche who was in charge and agreed to the formal surrender of Geronimo. This event marked the fall of the last free American Indian tribe, as every other tribe had been defeated or was living on a reservation.5

As of September 8, 1886, all of the Chiricahua Apaches who had surrendered to General Miles were sent on a train to Florida under the order of President Cleveland. They were also all made Prisoners of War (POW). The war department oversaw the Chiricahua Apaches, and since POW was the only category that the department saw fit for the tribe of Geronimo, they categorized all Chiricahua Apaches as Prisoners of War. This unfortunately included any Chiricahua Apaches who fought alongside the US military, and the scouts Katiyah and Martine, who had helped find Geronimo in order to surrender. The war department reached out to the Indian Bureau to get them to have liability over the Chiricahua, as they would any other tribe, but the Bureau refused. The Department of War then turned to the Interior Department and asked if they would find a reservation for the Chiricahuas. They also either ignored and stalled the process, or simply refused.6

On September 10, the train stopped in San Antonio, Texas, where the Chiricahua were ordered to disembark and were sent into tents. General Miles was sending reports to Washington DC, trying to figure out what to do with the tribe. President Cleveland wanted a trial and for them to be hung for their crimes, while Miles did not. Meanwhile, as the days went by, Geronimo and Naiche were growing scared that their people were going to be killed or split up. Countless generals, including General Miles, all assured Geronimo and Naiche that that would not happen on their watch. On October 22, forty-four days since they arrived in San Antonio, Geronimo and Naiche were informed that they found reservations for the tribe. In just a few hours, they would be loaded up onto trains, and the women and children would be sent to a reservation in Fort Marion. This was the location where other Chiricahua Apaches, who did not flee, had been for six months. The men would be located in Fort Pickens. Geronimo and Naiche did not agree and voiced their disapproval. But this did not matter; it was what the President ordered. The Chiricahua Apache were once again loaded up on trains, separated from their families; women in one train, the scouts in another, and men in a third car; and they were sent to another reservation.7

On October 25, 1886, the train came to a halt and unloaded Geronimo and the men at Fort Pickens, located in Pensacola, Florida. The men worked every day on the reservation for six hours a day, except on Sundays, and wrote to their wives and children in Fort Marion. A three-day event took place in Pensacola, where tourists from all over came to see the infamous Geronimo. He sold autographs and even consented to putting on a dance for the people. This became an important aspect of the Apaches’ reservation lives as they remained in the East. Many of the people who came to see the dance and get autographs were newspaper editors, and they gave Geronimo national attention, turning him and his Prisoners of Wars into national celebrities.8

After a little over a year of being on the reservation and still separated from loved ones, the Chiricahua Apache finally were reunited. The women, children, and scouts were sent to Mount Vernon, after growing concerns with overcrowding and other issues on Fort Marion, in April of 1887. After learning this, Geronimo begged and talked to reservation and military officials, until he finally got them to send the Chiricahua men to Mount Vernon on May 22, 1888.9 Their late arrival faced some challenges, mainly how to integrate the two groups while one had been living on the reservation a year prior to the arrival of those from Fort Pickens. But once again, tourists began arriving to take a peek at the infamous Geronimo, wanting to buy anything he made. The Chiricahua took notice that Geronimo-made items sold quicker and at a higher prices, so they began advertising that their items were made by Geronimo. The man and the tribe who had raided hundreds of people and killed thousands less than two years earlier, became a capitalist small business.10 They lived on the Mount Vernon Reservation for seven years until they were relocated to Fort Sill in Oklahoma, still with the label of Prisoners of War.11

The Chiricahua began making a better life for themselves as they worked six days a week, even in the cold winters, and were taught how to care for cattle. They had never cared for cattle and ended up not being great herders, but they did have success in spring planting. When Geronimo arrived at Fort Sill, he was seventy-one years old, but he too enjoyed gardening. He took great pride in his garden and enjoyed growing watermelons.12 However, despite his good behavior on the reservation, Fort Sill did not allow Geronimo to sell his craftwork as he had on previous reservations. Later that year, the Trans-Mississippi International Exposition of 1898 opened in Omaha, Nebraska. A major component of the exposition was “Indian congress,” which featured five hundred natives from thirty-five tribes. Attendees demanded they see Natives in “their native state,” so the Natives performed dances and conducted ceremonies. The Omaha exposition was Geronimo’s start to new heights of fame. With the assassination of President William McKinley, the current Vice President Theodore Roosevelt rose to the seat of Presidency. He then won the election of 1904 and claimed his inauguration parade would showcase Native Americans. Who better to lead the parade than the newly acclaimed celebrity, Geronimo.13

Despite good intentions, the inauguration parade was not joyful. On March 9, 1904, five days after the inauguration parade, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Francis E. Leipzig, took Geronimo and the other chiefs into the President’s Office at the White House.14 The chiefs and Roosevelt exchanged greetings, when a saddened and tearful Geronimo begged President Roosevelt to “take the ropes from the hands of my people and let us go back to the home of our fathers.” His cries continued, “We are tired of living in a strange country and we want to go home,” as Geronimo pleaded with the President, but he was met with refusal. “I cannot do so now. You must not forget that when you were in Arizona you had a bad heart… and you were not good Indians… We must wait a while before we can think of sending you back to Arizona,” the president replied through an interpreter. Geronimo, deeply upset, began speaking passionately in his native tongue, gesturing as he spoke, but was cut off. The President left the room as Geronimo began to plead: “I did not finish what I wished to say to the Great Father,” he cried. “I wanted to tell him that we would be good and would obey his wishes. If he would hear me through, I am sure he would let us go back home.” Mr. Leupp, the person appointed by Roosevelt to watch over the Chiricahua’s, replied, “The Great Father is very busy and has given you all the time he can spare…If you have anything more to say to him you must write it.” “Then I will write to him,” a still tearful Geronimo replied.15

Geronimo returned to Fort Sill and became acquainted with S.M. Barrett, who was the superintendent of nearby schools. They became friends and Geronimo told Barrett much of his life story as well as the history of his tribe. In the summer of 1905, Barrett asked Geronimo’s permission to publish much of what he had told him. At first, Geronimo refused, but due to his need to earn money, he agreed, but only if the military officer in charge agreed. The military official in charge was First Lieutenant George M. Purington, who ultimately refused the request. Barrett then decided to write directly to President Roosevelt, who quickly gave his consent, with the final review needing to be done by the War Department. In October 1905, Barrett secured an interpreter for Geronimo, who made it clear that he would simply talk, and there would be no interview questions given by Barrett. They completed the manuscript and mailed it to Roosevelt. It went through extreme criticism by the War Department, but once fixed, the novel was sent to publication.16

Geronimo dedicated his book to President Roosevelt, ending it with his final plea to be sent to Arizona: “It is my land, my home, my fathers’ land. I want to spend my last days there, and be buried among those mountains,” he wrote. Roosevelt read the book and his plea, but unfortunately did not grant his final wish.17

On February 11, 1909, Geronimo went into Lawton to sell bows and arrows. With the income, he asked a man named Eugene Chihuahua to buy him whiskey (Natives at this time were barred from buying alcohol). He did, and gave it to Geronimo. Later that night, an intoxicated Geronimo mounted his horse and began to ride back to Fort Sill. Almost there, Geronimo fell off his horse into the snow during the freezing weather. He was discovered the next morning, when his family took care of him for three days. They took him to a hospital where his cold was becoming progressively worse, until it developed into pneumonia. The doctor expected him to die quickly, but Geronimo waited until his children, Eva and Robert, had been brought to his bedside from the Chilocco Indian School. Geronimo died on February 17, 1909, without his children by his side.18

Geronimo, a prisoner of war for twenty-three years, was buried in the Apache graveyard on Cache Creek in Fort Sill, Oklahoma.19 One hundred years after Geronimo’s passing, on February 17, 2009, his great-grandson, Harlyn Geronimo, filed a lawsuit demanding that Geronimo’s remains be removed from Fort Sill and reburied in Arizona. “The only way to bring this to a closure,” Harlyn Geronimo said at a press conference, “is to release the remains and his spirit, so that he can be taken back to his homeland.”17 Unfortunately, the lawsuit was unsuccessful, and his remains are still located in Fort Sill. Geronimo has yet to return to his homeland in Arizona.

- Peter Carlson, “When Geronimo Met Teddy Roosevelt,” American History 44, no. 3 (August 1, 2009): 20–21. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 1-2. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 2-3. ↵

- Bill Cavaliere, “Geronimo’s Final Surrender,” Wild West 34 no. 2 (2021): 37-38. ↵

- Bill Cavaliere, “Geronimo’s Final Surrender,” Wild West 34 no. 2 (2021): 39. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 221-222. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 223-225. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 227-229. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 233-234. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo’s Last Years (Yale University Press, 2012), 236-238. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 247. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 248-254. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 255-257. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo’s Last Years (Yale University Press, 2012), 257-258. ↵

- New-York tribune, March 10, 1905, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1905-03-10/ed-1/seq-7/>. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 259-261. ↵

- Peter Carlson, “When Geronimo Met Teddy Roosevelt,” American History 44, no. 3 (August 1, 2009): 20–21. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 262. ↵

- Robert M. Utley, Geronimo (Yale University Press, 2012), 262. ↵

- Peter Carlson, “When Geronimo Met Teddy Roosevelt,” American History 44, no. 3 (August 1, 2009): 20–21. ↵

36 comments

Carina Martinez

Congratulations on the nomination on your article! This article is very well written and you included so many visuals, it made it very easy to read and enjoy! Stories like these need to be discussed more.

Lyle Ballesteros

I really enjoyed reading this article. I had never heard of Geronimo before but I feel like now I know his whole life story. He seems to be a really interesting character. TO be the kind of unofficial leader of his tribe and a person that attacked and killed thousands of people to create the reputation that got the AMerican government involved, to now being a popular figure where tourists come to get his autographs while he is still considered a war criminal and invited by new president Roosevelt to be at the parade. I find that interesting and how people find people who would be considered bad, fascninating and something to be a tourist for.

Melyna Martinez

This article shows the impact Native Americans have in history and yet many of these stories are unknown. You can see that Geromino’s story is one of determination and will to fight for one’s beliefs even when he was not liked. He did everything to show the victimization of Native Americans in situations imposed by colonizers. It is sad to see that he died and his remains did not make it back to his home, but his impact was strong.

Hunter Stiles

I want to start by congratulating you on your nomination. I enjoy the conversation between Woodworth Clum and President Roosevelt in the article’s opening. I had heard of Geronimo before reading the story, but I was unaware of his raids against Mexicans. It was fascinating to observe how Geronimo and other war criminals rose to national notoriety. Overall, the piece was well-written and did a great job of conveying Geronomio’s yearning to go back to Arizona.

Guiliana Devora

Geronimo did some questionable things when people are looking at his story, but for him and his own culture at the time were always in jeopardy of being killed. This was an incredible story of a man and the author did an amazing job of telling it. The way the author wrote this article made me wan to keep reading line after line. I still think it is incredible sad that Geronimo did not get his last dying wish to be buried in Arizona and I believe he should be.

Marissa Rendon

Congratulations on your award nomination! I liked the dialogue between Roosevelt and Clum at the beginning of the article. I did not realize how impactful Native Americans were in history up until I read this article. I like the pictures that were used throughout the article ! They were very informative and truly helped the article come to life.

Jacob Adams

This was a great article that highlights another story that has been suppressed by American media. Lots of Native American history is lost because if the way we suppressed and treated these people as sub-human. Although it was nice that Roosevelt approved the writing of his story, it was not right that he was not able to be buried in arizona. The pictures were great and kept me engaged throughout the reading. This had many well cited sources as well.

Danielle Sanchez

Congratulations on your nomination! This article contained great images that carried the story along! After years of raiding and attacking Mexican soldiers and people of Mexico and Arizona, Geronimo was sent to an Apache reservation in Sierra Madre in 1876. He had escaped the reservation three times, which allowed him to execute all forms of raids and acquire a record of brutality unlike any other native in his time. He had escaped the reservation three times, which allowed him to execute all forms of raids and acquire a record of brutality unlike any other native in his time.

Gabriella Galdeano

Congratulations on the nominations for this article! I really liked your writing style and the pictures you used. You showed how important and respected he was within his tribe despite not being a chief. I was saddened to learn that he never got to go home to Arizona. I hope one day, his final wish can be fulfilled.

Muhammad Hammad Zafar

It was sad that he dedicated book to President Roosevelt and asked to be sent to Arizona to be buried there but was not granted his last wish. His Grandson Harlyn Geronimo said at press conference to release his remains and to be taken back to Arizona which was again unsuccessful.