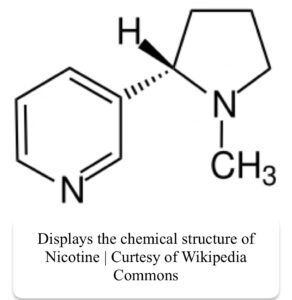

Do you ever wonder what it’s like to “hit” your friend’s vape or what happens inside your body when you take a “hit”? Flavored vapes and other scented e-cigarettes have been known to contain multitudes of toxic chemicals that disrupt the biological processes within the body. However,  the most talked about substance is nicotine. Nicotine is a widely used substance by many age groups in America, most common in young adults. Usually, this substance is found and used in e-cigarettes, cigars, vaping devices, and hookahs1, as well as nicotine patches and gum. Nicotine is mainly derived from the tobacco plant 2 but can be found in other vegetables. It belongs to the alkaloids family, and its IUPAC chemical name is 3-(1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)pyridine (C10H14N2).3 Nicotine has been proven to affect the cardiac and respiratory systems by increasing an individual’s blood pressure, breathing, and heart rate.1 It also affects the central nervous system (CNS), primarily the brain.

the most talked about substance is nicotine. Nicotine is a widely used substance by many age groups in America, most common in young adults. Usually, this substance is found and used in e-cigarettes, cigars, vaping devices, and hookahs1, as well as nicotine patches and gum. Nicotine is mainly derived from the tobacco plant 2 but can be found in other vegetables. It belongs to the alkaloids family, and its IUPAC chemical name is 3-(1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)pyridine (C10H14N2).3 Nicotine has been proven to affect the cardiac and respiratory systems by increasing an individual’s blood pressure, breathing, and heart rate.1 It also affects the central nervous system (CNS), primarily the brain.

Vaping and other e-cigarette companies primarily target the younger audience in advertising campaigns. Their slim design allows younger audiences to vape in public areas more discreetly. Carrying these items is also more convenient as they are more efficient than the large bulky ones. In a single Juul pod, there are roughly 40 mg of nicotine, equivalent to a pack of cigarettes, smoking a total of 20 cigarettes.5 According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), in 2014, companies were estimated to spend about 115 million dollars advertising their e-cigarette and nicotine products. These companies seek to market to vulnerable individuals to increase their product demand. Based on multiple studies, the neuroscience community has concluded that the human brain does not fully develop until one has reached their mid to late twenties.3 Since brain development is incomplete in young adults, they become more susceptible to  mental health issues, addiction, and other substances.7 Nicotine can induce euphoria, anxiety, and mood disorders, alterations in impulse control,8 delay brain maturation in teens and young adults,9 and in some cases lead to addiction.2

mental health issues, addiction, and other substances.7 Nicotine can induce euphoria, anxiety, and mood disorders, alterations in impulse control,8 delay brain maturation in teens and young adults,9 and in some cases lead to addiction.2

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), nicotine is “an addictive, poisonous chemical found in tobacco.11 When nicotine enters the body, it takes roughly 8 seconds for the brain to absorb it.12 Nicotine, also known as a gateway drug2; the exposure to a drug that stimulates the exploration of other substances. It can lead to experimenting with other drugs and substances such as inhalants, anabolic steroids, marijuana, alcohol, prescription drugs such as Adderall, and many others. Nicotine products encourage susceptible individuals to experiment with neighboring drugs, which could lead to nicotine addiction or of other substances.

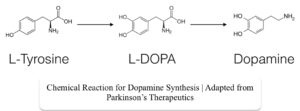

Consumption of nicotine becomes addictive due to dopamine release within the brain. Dopamine is a monoamine neurotransmitter, a derivative of the amino acid tyrosine. Neurotransmitters derived from tyrosine are referred to as the catecholamine family. This structural family comprises epinephrine (noradrenaline), norepinephrine (adrenaline), and dopamine.14 Dopamine entails causing motivation, rewarding feelings, reinforcement, and aiding body movement coordination. This neurotransmitter is produced by converting tyrosine into L-DOPA, decarboxylated into dopamine. It is mainly concentrated in the substantia nigra, the ventral tegmental area within the midbrain14, and the hypothalamus.16 There are also a few pathways within the brain that focus on the release of dopamine. The nigrostriatal pathway runs from the substantia nigra to the striatum and holds about 80% of the dopamine in the brain. This pathway is involved in the body’s motor movement, and low dopamine levels are often associated with Parkinson’s disease.17 The mesocortical pathway runs from the ventral tegmental area to the prefrontal cortex.16, 17 Its physiological focus relates to cognitive, emotional, and executive functions.17 The mesolimbic pathway runs from the ventral tegmental area to the cerebral cortex.16 It is essential for increasing motivation, rewarding feelings, and stimulating emotions.14 It is also related to showing symptoms of schizophrenia. The tuberoinfundibular  pathway stretches from the hypothalamus to the infundibular region, which allows dopamine to stimulate the inhibition of prolactin release in the anterior pituitary gland.17 Dopamine receptors act as G protein-coupled receptors in the central nervous system.14 There are 5 different receptors; D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5.12 It has been found that nicotine exposure to D2 receptors increases the number of dopamine receptors (D2HIGH) found as well as hypersensitivity.26 Most nicotine studies have focused on the effects on dopamine receptors D2 and D4, which results in less knowledge regarding its effects on D1 and D3 receptors. However, this substance does interact with the rest of the receptors, but its complete mechanism is unknown.

pathway stretches from the hypothalamus to the infundibular region, which allows dopamine to stimulate the inhibition of prolactin release in the anterior pituitary gland.17 Dopamine receptors act as G protein-coupled receptors in the central nervous system.14 There are 5 different receptors; D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5.12 It has been found that nicotine exposure to D2 receptors increases the number of dopamine receptors (D2HIGH) found as well as hypersensitivity.26 Most nicotine studies have focused on the effects on dopamine receptors D2 and D4, which results in less knowledge regarding its effects on D1 and D3 receptors. However, this substance does interact with the rest of the receptors, but its complete mechanism is unknown.

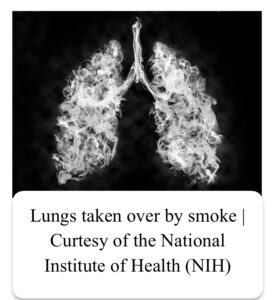

When nicotine is administered into the body through a vape or e-cigarette, it enters the respiratory system by inhalation. Soon after the substance is inside the lungs, it enters the bloodstream. As nicotine enters the body, it can increase blood pressure and stimulate relaxation, tachycardia, and narrowing of the arteries, thereby limiting the oxygen delivered to the heart.27, 28 The blood will travel to the heart, where it is then pumped to other areas of the body, and the other organ systems begin to process this substance. Once the blood carrying nicotine reaches the brain, it binds to neuronal receptors. These receptors receive the chemical signal, which induces an action potential releasing the dopamine neurotransmitter in the synaptic area of the synapse. In the action potential, L-tyrosine is converted to its dopamine derivative, which is then excepted for transportation. Once the dopamine release has occurred, the body begins to experience the “rewarding feeling” of consuming nicotine. When there is a constant stimulus of dopamine receptors due to nicotine consumption, the brain is tricked into believing that it needs to continue its ingestion of the substance. This chemical overstimulates these receptors, and the brain develops a tolerance to it, therefore requiring more “hits.” 29 The release of this neurotransmitter after one hit causes the brain to get accustomed to the synaptic dopamine release, which then increases the chances of addiction.30

A study found that different nicotine concentrations caused an influx of calcium (Ca2+) ions in the midbrain ventral tegmental area (VTA) dopamine-related neurons.31 To enter this brain region, nicotine must cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to be absorbed. Researchers found that nicotine can cross the blood-brain barrier in “…only 2.2-4.4 seconds to initiate its response and 16-19 seconds to reach peak activation level.” Also that at higher concentrations, the mouse locomotor activity (measurement of behavior) decreased, which correlated to the rapid increase of Ca2+ ions in their dopamine neurons.31 That being said, calcium is essential for releasing dopamine in the brain. Another study found that nicotine at low concentrations resulted in desensitized midbrain dopamine neurons. Also,“…nicotine obtained by smoking can acutely excite dopaminergic VTA dopamine release to fire action potentials…” The excitation in the VTA would explain how and why nicotine tolerance is developed over time.30, 34 As we can conclude from the two studies, as more dopamine is initially released due to the performance of a certain action (consuming vapes and e-cigarettes with nicotine), the more the brain requires it.

According to Drugs and Society (Venturelli, 2020), evidence has shown a correlation between substance addiction and mental health disorders. In general, four principal factors affect substance abuse; biological, genetic, pharmacological, cultural, social, and contextual. The first principal, biological, genetic, and pharmacological factors, depends on the drug’s pharmacology [in this case, nicotine] and how its chemical structure interacts with the biological processes within the body. The second principle, cultural factors, involves societal views on the substance.  It can be based on the religious tradition and cultural customs determining an individual’s substance consumption approach. Thirdly, social factors focus on the individual’s reason for taking the drug, “What is the overall reason for consuming said substance [nicotine]?” Lastly, contextual factors involve an individual’s environment when a drug is being distributed. This can include nightclubs, parties, music concerts/events, etc. 30 These factors bleed into the three types of substance users; experimenters, compulsive users, and floaters (also referred to as “chippers”). Experimenters are individuals that are curious and open to trying a substance. This is often a result of peer pressure and/or their environment. Compulsive users are individuals who devote their time to obtaining the high and constantly converse about their use. They are the people that are termed to be connoisseurs of that or more drugs. Floaters are individuals that seek to get ahold of other people’s drug supply rather than building their own.30 That being said, when does drug use lead to addiction? It begins with excessively seeking a substance (nicotine), then moves into worrying about one’s drug supply, eventually transitioning into denial about excessive use and finally dependency on the substance.

It can be based on the religious tradition and cultural customs determining an individual’s substance consumption approach. Thirdly, social factors focus on the individual’s reason for taking the drug, “What is the overall reason for consuming said substance [nicotine]?” Lastly, contextual factors involve an individual’s environment when a drug is being distributed. This can include nightclubs, parties, music concerts/events, etc. 30 These factors bleed into the three types of substance users; experimenters, compulsive users, and floaters (also referred to as “chippers”). Experimenters are individuals that are curious and open to trying a substance. This is often a result of peer pressure and/or their environment. Compulsive users are individuals who devote their time to obtaining the high and constantly converse about their use. They are the people that are termed to be connoisseurs of that or more drugs. Floaters are individuals that seek to get ahold of other people’s drug supply rather than building their own.30 That being said, when does drug use lead to addiction? It begins with excessively seeking a substance (nicotine), then moves into worrying about one’s drug supply, eventually transitioning into denial about excessive use and finally dependency on the substance.

Many factors contribute to drug abuse and its dependence. There is physical and psychological dependence. Physical dependence focuses on substance consumption to prevent the body from experiencing withdrawal symptoms. Psychological dependence involves the mental qualities that addictive qualities a person has (emotions, change in personality, etc.). This can relate to the feeling the substance induces in their personality and mood or to relieve any discomfort resulting from withdrawal effects. However, drug dependence is different from addiction. Dependence consists of five stages and revolves around increased use, preoccupation, dependency, and withdrawal. The first stage, relief, is the contentment and pleasure an individual experiences after consuming a substance. Increased use relies on taking greater drug quantities to reach the potency threshold. Preoccupation is the constant concern about consuming a drug. Dependency or addiction is when a substance is consumed despite any present physical symptoms (excessive sweating, dilated pupils, eyes, etc.). Withdrawal focuses on the negative physical and psychological effects of not consuming the desired substance. Drug addiction is somewhat related to dependence but differs in how it is classified. It comprises seven stages; pharmacological, time, craving of substance, social impairment, risk, tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms.30 The pharmacological stage relates to increasing the substance dosage every time it is taken. Time involves excessive time spent trying to get ahold of drugs. Craving(s) of a substance is the urgency to consume the desired drug. The risk associated with consumption can vary between the psychological and physical effects the body has in response to a substance. Tolerance focuses on an individual needing to over-consume to experience a high. If they do not increase their dosage, their body will not reach the threshold to produce intoxicated effects. This often occurs because the body develops a tolerance to the substance. Therefore, the cravings intensify. Lastly, withdrawal symptoms arise when an individual has not consumed the drug. As a result, the body begins to experience physical and psychological reactions. A person can experience irritability, nausea, excessive sweating, personality and mood changes, etc.30

In conclusion, nicotine can induce multiple effects throughout the body but mainly become addictive to the brain. Though there is still some gray area revolving the effects of this substance on dopamine receptors as the mechanisms of dopamine have not been fully studied, some knowledge of its function and chemical and behavioral effect is still unknown. Nicotine can damage an individual’s learning ability since it also affects the development of synapse formation in the frontal lobe region of the brain.39 This brain area primarily focuses on learned behavior, personality development, and emotional control. Dopamine has been associated with many mental processes, such as memory, arousal, sleep regulation, attention span, and many others.40 As a result of the over-consumption of nicotine, the brain feels the urge to continue taking a hit, essentially becoming a learned behavior to induce the reward pathway yet never being satisfied. The more an individual partakes in this activity, the harder it becomes to stop due to the withdrawal of physical and psychological symptoms. According to Fast Facts, “…only 12% of teen smokers who tried to quit were able to do so successfully…” (2023).12 That being said, as a society, how should we approach nicotine and its effects while also considering its potential addiction in our youth?

- “Mind Matters: The Body’s Response to Nicotine, Tobacco and Vaping.” National

Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, June 13, 2022. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/parents-educators/lesson-plans/mind-matters/nicotine -tobacco-vaping#:~:text=How%20does%20nicotine%20work%3F,good%20feelings%20 all%20at%20once. ↵ - Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 2: Addiction and

Drug Abuse Models.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett

Learning, 2022. ↵ - “Nicotine.” National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Nicotine. ↵

- “Mind Matters: The Body’s Response to Nicotine, Tobacco and Vaping.” National

Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, June 13, 2022. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/parents-educators/lesson-plans/mind-matters/nicotine -tobacco-vaping#:~:text=How%20does%20nicotine%20work%3F,good%20feelings%20 all%20at%20once. ↵ - Prochaska, Judith J, Erin A Vogel, and Neal Benowitz. “Nicotine Delivery and Cigarette

Equivalents from Vaping a Juulpod.” Tobacco Control. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd,

August 1, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056367. ↵ - “Nicotine.” National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Nicotine. ↵

- “The Teen Brain: 7 Things to Know.” National Institute of Mental Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed April 12, 2023. ↵

- “Know the Risks of e-Cigarettes for Young People: Know the Risks: E-Cigarettes & Young People: U.S. Surgeon General’s Report.” E. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/knowtherisks.html#:~:text=Brain%20Risks,-The %20part%20of&text=These%20risks%20include%20nicotine%20addiction,that%20cont rol%20attention%20and%20learning. ↵

- Goriounova, Natalia A, and Huibert D Mansvelder. “Short- and Long-Term Consequences of Nicotine Exposure during Adolescence for Prefrontal Cortex Neuronal Network Function.” Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine, December 1, 2012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3543069/. ↵

- Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 2: Addiction and

Drug Abuse Models.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett

Learning, 2022. ↵ - “NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms.” National Cancer Institute. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/nicotine. ↵

- “Fast Facts.” Choose Nicotine Free. Accessed April 12, 2023.

http://www.aahealth.org/nicotinefreeweek/fast-facts/. ↵ - Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 2: Addiction and

Drug Abuse Models.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett

Learning, 2022. ↵ - Purves, Dale, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, William C. Hall, Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, Richard D. Mooney, Michael L. Platt, et al. “Chapter 6: Neurotransmitters and Their Receptors.” Essay. In Neurosciences, 6th ed., 113–43. Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck Supérieur, 2019. ↵

- Purves, Dale, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, William C. Hall, Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, Richard D. Mooney, Michael L. Platt, et al. “Chapter 6: Neurotransmitters and Their Receptors.” Essay. In Neurosciences, 6th ed., 113–43. Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck Supérieur, 2019. ↵

- 2-Minute Neuroscience: Dopamine. Neuroscientifically Challenged, 2018.

https://youtu.be/Wa8_nLwQIpg. ↵ - Dopamine Pathways, Antipsychotics and Schizophrenia . Psychopharmacology Institute,

2012. https://youtu.be/5wM2oqQJhV4 ↵ - 2-Minute Neuroscience: Dopamine. Neuroscientifically Challenged, 2018.

https://youtu.be/Wa8_nLwQIpg. ↵ - Dopamine Pathways, Antipsychotics and Schizophrenia . Psychopharmacology Institute,

2012. https://youtu.be/5wM2oqQJhV4 ↵ - Dopamine Pathways, Antipsychotics and Schizophrenia . Psychopharmacology Institute,

2012. https://youtu.be/5wM2oqQJhV4 ↵ - 2-Minute Neuroscience: Dopamine. Neuroscientifically Challenged, 2018.

https://youtu.be/Wa8_nLwQIpg. ↵ - Purves, Dale, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, William C. Hall, Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, Richard D. Mooney, Michael L. Platt, et al. “Chapter 6: Neurotransmitters and Their Receptors.” Essay. In Neurosciences, 6th ed., 113–43. Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck Supérieur, 2019. ↵

- Dopamine Pathways, Antipsychotics and Schizophrenia . Psychopharmacology Institute,

2012. https://youtu.be/5wM2oqQJhV4 ↵ - Purves, Dale, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, William C. Hall, Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, Richard D. Mooney, Michael L. Platt, et al. “Chapter 6: Neurotransmitters and Their Receptors.” Essay. In Neurosciences, 6th ed., 113–43. Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck Supérieur, 2019. ↵

- “Fast Facts.” Choose Nicotine Free. Accessed April 12, 2023.

http://www.aahealth.org/nicotinefreeweek/fast-facts/. ↵ - Novak, G., Seeman, P., & Foll, B. L. Exposure to Nicotine Produces an Increase in Dopamine D2^^High^^ Receptors: A Possible Mechanism for Dopamine Hypersensitivity. International Journal of Neuroscience, 120(11), 691–697. ↵

- NCI Dictionary of Cancer terms. National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/nicotine. ↵

- “How Smoking and Nicotine Damage Your Body.” www.heart.org, January 24, 2023.

https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-lifestyle/quit-smoking-tobacco/how-smo

king-and-nicotine-damage-your-body. ↵ - Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 11: Tobacco.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2022. ↵

- Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 2: Addiction and

Drug Abuse Models.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett

Learning, 2022. ↵ - Wei, Chao, Xiao Han, Danwei Weng, Qiru Feng, Xiangbing Qi, Jin Li, and Minmin Luo. “Response Dynamics of Midbrain Dopamine Neurons and Serotonin Neurons to Heroin, Nicotine, Cocaine, and MDMA.” Nature News. Nature Publishing Group, November 6, 2018. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41421-018-0060-z#citeas. ↵

- Wei, Chao, Xiao Han, Danwei Weng, Qiru Feng, Xiangbing Qi, Jin Li, and Minmin Luo. “Response Dynamics of Midbrain Dopamine Neurons and Serotonin Neurons to Heroin, Nicotine, Cocaine, and MDMA.” Nature News. Nature Publishing Group, November 6, 2018. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41421-018-0060-z#citeas. ↵

- Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 2: Addiction and

Drug Abuse Models.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett

Learning, 2022. ↵ - Volodymyr I. Pidoplichko & Mariella DeBiasi & John T. Williams & John A. Dani. “Nicotine Activates and Desensitizes Midbrain Dopamine Neuron.” Nature. Nature, January 1, 1997. https://ideas.repec.org/a/nat/nature/v390y1997i6658d10.1038_37120.html. ↵

- Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 2: Addiction and

Drug Abuse Models.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett

Learning, 2022. ↵ - Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 2: Addiction and

Drug Abuse Models.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett

Learning, 2022. ↵ - Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 2: Addiction and

Drug Abuse Models.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett

Learning, 2022. ↵ - Hanson, Glen, Peter J. Venturelli, and Annette E. Fleckenstein. “Chapter 2: Addiction and

Drug Abuse Models.” Essay. In Drugs and Society. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett

Learning, 2022. ↵ - Vaping: The Hit Your Brain Takes. Addiction Policy Forum , 2019.

https://youtu.be/aasKIDz9ZX4. ↵ - 2-Minute Neuroscience: Dopamine. Neuroscientifically Challenged, 2018.

https://youtu.be/Wa8_nLwQIpg. ↵ - “Fast Facts.” Choose Nicotine Free. Accessed April 12, 2023.

http://www.aahealth.org/nicotinefreeweek/fast-facts/. ↵

5 comments

Natalia De La Garza

Thank you for providing us with this informative piece! It’s truly eye-opening, and I think more people need to understand just how harmful vapes can be. This information is crucial for raising awareness and helping others make better choices for their health.

Vanessa Jimenez

What an insightful and timely article that speaks to our over wellness that explores all aspects of the effects of vaping on one’s health and the societal impact that delves deep into the science of the substance and the interaction that lead to addiction!

Carlos.C

Great article!!! Bringing attention to the effects of nicotine on the brain. Good job!

Carlos. C

This is a great article!!! Bringing attention to the effects of nicotine on the brain. Great job!

Kyle Chormanski

This does a great job explaining the cause of some of the problems of smoking/vaping. Great work, keep it up! I feel like Organic Chemistry 2 did a great job preparing you for this publication.