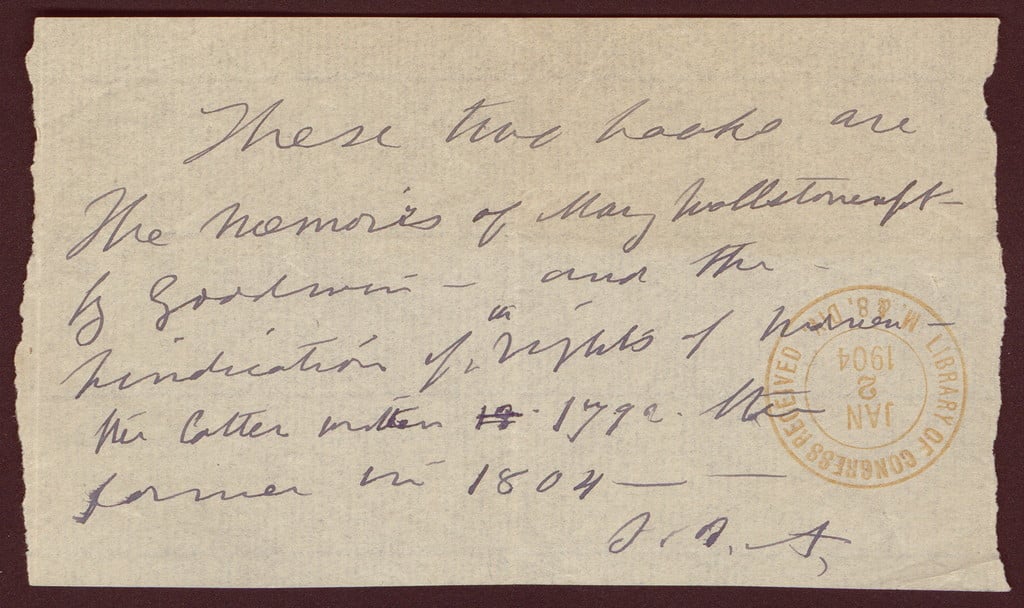

When people hear the name Mary Wollstonecraft, the thought of her daughter: Mary Shelly Wollstonecraft and a variety of Shelly’s popular novels such as Frankenstein or Mathilda often come to mind. Few individuals know of Mary Wollstonecraft and the weight and strength her name holds. Her works of writing criticized and disrupted the lives of men in the late 18th century and aimed to break the horrific “societal norms” imposed on women of her time. Scholars often describe her to be a “moral” or “political” philosopher, as well as a cornerstone for women’s rights in the late 18th century. Drawing on Wollstonecraft’s literature, specifically: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman1, excerpts from various secondary sources, namely: An Analysis of Mary Wollstonecraft’s: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman2, it can be argued that Wollstonecraft was, and still is without a doubt, a social critic and advocate for women’s rights. Her contributions influenced numerous advocates to take a stand and inspired an array of social criticisms in literature.

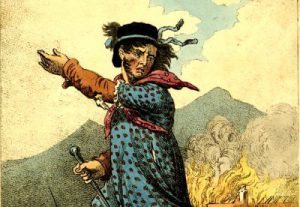

Wollstonecraft was born in 1759 when societal views were patriarchal and rigid. These rules followed by the populace sought to impose and dictate how both women and men should live their life within the social system. Men had devised outlandish theories in order to deny women of their character or the pursuit of intelligence, such as Darwinian psychiatry,3 which stated that since the size of a woman’s skull was smaller, they lacked the brain capacity to be an intelligent being, unlike their male counterparts. The theory of the bifurcated female4 was also a prominent idea that claimed that there were only two types of women: the Madonna/angel, a pure woman who served her husband, or the femme fatale, the evil woman who deferred from the ideal woman or one who bewitched men. These labels and “scientific facts” were used as a basis to enforce arbitrary rules on women, and an excuse to give them little to no place in the societal sphere. If a woman was too pretty or cared about her image too much, she was considered vain. If she had a sexual drive or had pleasure in intercourse with her husband, she was deemed a femme fatale or a lethal woman. It was thought that a woman should not express great intellectual knowledge, as it was considered an unattractive trait for them to have. These educated women were seen to be trying to “mimic” the character of a man. They were referred to as “Blue-stockings [and] were considered unfeminine and off-putting in the way that they attempted to usurp men’s ‘natural’ intellectual superiority. Some doctors reported that too much study actually had a damaging effect on the ovaries, turning attractive young women into dried-up prunes.”5 Wollstonecraft despised this view of women and criticized it in the Rights of Women: “Men complain, and with reason, of the follies and caprices of our sex, when they do not keenly satirize our headstrong passions and groveling vices.- Behold, I should answer, the natural effect of ignorance!”6 However, many Victorians considered their view as essential and anything but ignorant. The role of a woman was to be a wife and a mother, to care for the house, and ultimately live to please their husband. They must remain beautiful, pure, and obedient; the image of perfection, a doll without a soul.

Wollstonecraft saw these issues within society and took to writing to illustrate and voice criticisms against the treatment of women, mothers, and even those experiencing poverty due to their social or political classes. Her novel, “The Wrongs of Woman is clear on the political, economic and legal ills of women, the wife’s inability to own property, her lack of rights over her children when separated, the physical and financial abuse of men, together with the salve: the help women might give each other across class.”7 Wollstonecraft was irked by the treatment of mothers, especially those who endured physical abuse or inhumane treatment at the hands of their husbands. These wives were expected to endure their circumstances and were either ignored or criticized for speaking out. Wollstonecraft called for women across social classes to join together and advocate for the role of women in the home and social sphere by identifying the hypocrisy of men and their practices. If men were able to exist socially, going to work, gaining an education, and living out their hopes and dreams all while being a “parental figure” why couldn’t women, who were capable of doing work, being educated, and being a caregiver not have the opportunity to do the same? Wollstonecraft’s social commentary was based on an array of observations and her personal experiences as well. One notable moment in her life, where she had experienced the fear of societal views and ostracization when she was pregnant out of wedlock, inspired her to write and “describe the fears of a pregnant unwed girl” in the Wrongs of Women.8 Women who became pregnant outside of wedlock, whether it was by prostitution, rape, or an affair, were deemed promiscuous sexual deviants who didn’t work hard enough to protect their purity. There was little sympathy for these women, as there were no social programs or ways for them to get the help they needed. Many of these women were left to dwindle in ever-increasing poverty unless, by a miracle, they were able to find work and provide for themselves.

Wollstonecraft went on to write several other novels that focused on bringing light to the horrific treatment of women, her most popular criticism being: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman 9. “In Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft argues that many of the differences between men and women are not the result of their biology or spiritual natures, but of their education and upbringing.”10 A major factor in the Victorian system was their segmentation and limited opportunities determined by social class; those who were born into, and inherited wealth had opportunities for education, while those born into poverty had little chance to improve or rise in class. The rift between each class was immense but upper-class Victorians endorsed this society, due to the benefits they received from it. Wollstonecraft challenged the foundation of the English society and advocated eliminating prejudice between men and women. If the individuals of the higher classes are not aware of the consequences that follow their treatment of the lower class, and they should recognize their misdeeds. If it’s the rules of society that shape and influence these practices that are both detrimental to men and women, there must be change, and its start began with the fall of its rigid classist system.

The publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Women11 was unsurprisingly met with resistance, as critics of Wollstonecraft’s writings were less than pleased with her commentary on the role of women, men, and classes, namely because she was a woman unleashing criticism in a patriarchal society. This left a bad taste in many observers’ mouths, specifically “the phrase ‘the Rights of Woman’ [that] shocked those liberals who insisted on leaving women out of the political sphere.”12 Unlike her prior writing of criticism: A Vindication of the Rights of Men, her new publication had her name on it. This factor made it easy for critics to identify her, with Horace Walpole nicknaming her a “hyena in petticoats,”13 a lowly beast who donned a woman’s garments to trick males and females alike. One of her largest critics was none other than Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who disagreed with her views on educating women. “Rousseau thought education should be based on espousing and exploring the natural abilities of a person. Therefore, since women have a natural responsibility of caregiving, their education should be given in line with helping them to enhance these natural caring abilities.”14 Wollstonecraft completely disagreed and challenged his opinion in The Rights of Woman, where she claimed that the intellect of women cannot be judged in a society that dictates what their intellects or capabilities are without even letting women see or explore their limits. If women are placed into a small box and dictated on what they can or cannot do, their natural abilities will never be able to flourish, let alone be appreciated. Wollstonecraft shut down this narrative, lambasting Rosseau for his harmful agenda concerning women’s educational intelligence and abilities. “I may be accused of arrogance; still I must declare, what I firmly believe, that all the writers who have written on the subject of female education and manners, from Rousseau to Dr. Gregory, have contributed to render women more artificial, weaker characters than they would otherwise have been; and, consequently, more useless members of society.”15 She articulated her stance further by questioning the freedom allowed to men in education, that those of the lower class are rejected from pursuing higher education due to finances and class, thus they are unable to express their fullest capabilities and intellect. How are the natural capabilities of men or women possibly explored in such a stunted society? If a patriarchal society is unable to solve these problems for men and enhance their lives, they should not impose these wild expectations on women.

Even though today’s society has steered far from the patriarchal society of the late 18th to early 19th century, individuals in certain countries are still experiencing many of the lingering effects. Unfortunately, unfounded beliefs and crimes committed hundreds of years ago don’t just disappear, individuals in society have to make an effort and fight for change. Around the world, many women are still seen as mere objects and treated as lesser beings, being forced into lives they do not wish to live. Wollstonecraft and other women laid the foundation for present individuals to follow. Women are more than their outward appearances and reproductive organs. They are living, breathing, human beings who deserve to be treated as such. Until there is change where both women and men are treated equally, individuals must push for change. It is time to stop standing complacently, “It is time to effect a revolution in female manners- time to restore to them their lost dignity- and make them, as a part of the human species, labour by reforming themselves to reform the world.”16

- Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Project Gutenburg, 2002) ↵

- Ruth Scobie, An Analysis of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Milton, UNKNOWN : Macat Library, 2017) ↵

- Michael McGuire and Alfonso Troisi, Darwinian Psychiatry. (2017). ↵

- Megan Shaw, Femininity: The Femme Fatale And The Fallen Woman. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). ↵

- Kathryn Hughes, Gender Roles in the 19th Century. (British Library). ↵

- Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Project Gutenburg, 2002), 19. ↵

- Janet Todd, Mary Wollstonecraft: a Revolutionary Life. (New York : Columbia University Press, 2000), 430. ↵

- Janet Todd, Mary Wollstonecraft: a Revolutionary Life. (New York : Columbia University Press, 2000), 416. ↵

- Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Project Gutenburg, 2002) ↵

- Ruth Scobie, An Analysis of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Milton, UNKNOWN : Macat Library, 2017), 11. ↵

- Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Project Gutenburg, 2002) ↵

- Janet Todd, Mary Wollstonecraft: a Revolutionary Life. (New York : Columbia University Press, 2000). ↵

- Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Project Gutenburg, 2002), 47. ↵

- Clifford Owusu-Gyamfi, Who Won the Debate in Women Education? Rousseau or

Wollstonecraft? (Journal of Education and Practice, 2016), 191. ↵

- Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Project Gutenburg, 2002), 60. ↵

- Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. (Project Gutenburg, 2002), 47. ↵