Introduction

The United States is currently facing issues concerning immigration due to an influx of individuals attempting to flee or leave their home countries whether it be for personal, safety, or economic reasons. However, there are rarely any news articles covering an immigration crisis in Europe that reaches the diversity of the border situation in the United States. The United States’ immigration system needs to be improved, and by analyzing countries in Europe like the United Kingdom, Germany, and Spain and applying their ideas and procedures to the current system, the United States can alleviate the current immigration issues. The research being examined and discussed will be a comparative analysis between the United States and Europe regarding immigration. The questions will be as follows: What can the United States do to improve the immigration system compared to Europe? What ideas and procedures could the United States adopt to alleviate the current immigration issue?

United States Immigration Background and Policy

The United States is a country built on the ideas brought by immigrants. To understand the foundation of immigration in the US one must first understand some key terms. Immigration is defined as the act or instance of traveling into a country for permanent residence there (“Immigration definition & meaning“). According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), an asylum seeker or refugee is a person who is outside of their country and is unable or unwilling to return home because they fear serious harm (“Refugees and asylum“). The Founding Fathers are examples of immigrants who left their country seeking refuge. In a tragic turn, these founding immigrants brought other immigrants from Africa and other countries to use them for slave labor.

Further, the United States was on its way to becoming a model of liberal democracy, and immigration was encouraged for numerous reasons in the early days. Scheid states, “Immigration is also important to the United States because it stimulates economic growth, increases innovation, and positively contributes to government finances, among other constructive impacts” (525). Recently, immigration policies have drastically changed despite these benefits. Previous President, Donald Trump, promoted new ideas such as a border wall, a plan to deport Mexican and Latin American immigrants who are protected under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Act (DACA), his restriction of travel and work visas for primarily Muslim countries, increased refugee screening, and increased limits to legal immigration thereby creating a divisive rhetoric and aggressive position towards immigration. In contrast to Trump, during Obama’s presidency, he utilized executive action to give protected status to immigrants who came to the United States as children, also known as DACA. However, Obama’s administration was also known for deporting many immigrants.

Under the Trump administration, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detentions rose to a daily average of over 45,000, and initial bookings exceeded 274,798 at ICE facilities as of 2019 (Sheid 529). Some Americans, inspired by Trump’s ideology, claim that immigrants are receiving government welfare assistance for free or are taking advantage of benefits that should only be reserved for “true” citizens and are claiming that undocumented immigrants are criminals or even terrorists (Scheid 526). Moreover, it is essential to remember that the legal migration process is not quick or easy, so most immigrants choose to cross over without documentation. According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), individuals applying for green cards must be eligible and, in most cases, have a sponsor in the United States to file the petition. There are different processes for individuals residing in the United States or applying from outside of the United States. Then, USCIS must approve the application, and a visa must be available in their category. If the individual makes it through this process, they must attend a biometrics appointment and an interview. After all of this, they receive a decision on their application. This process requires fees that some individuals may not be able to afford and requires time and specific criteria to be met. Many families may be unable to afford this process, or their application gets denied due to high volumes of applications, or their application takes a long time to be considered. These immigrants seek a better life with better job opportunities or escape persecution. However, during his presidency, Trump pushed for a one-hundred percent prosecution rate of those who have entered or re-entered the country “illegally,” Scheid further states, “Trump immigration policy has also increased separation of children from their parents when the parents are taken into criminal custody, whether or not they have committed serious crimes aside from being in the U.S. illegally” (529).

More recently, the Biden administration has raised legal tensions between the government and certain border states. A recent and relevant case is United States v. Texas (2023). The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued guidelines in September of 2021 for the Enforcement of Civil Immigration Law. The law requires that federal government officials exercise discretionary authority in a targeted way to focus their efforts on those who pose a threat to national security, public safety, and border security. When exercising this discretion, they are aware that a majority of undocumented noncitizens who may be subject to removal have been contributing members of communities for years (“Guidelines for the enforcement of civil immigration law”). Prioritizing apprehension for noncitizens who pose a threat would allocate resources. It would carefully allow the Department to exercise its discretionary authority in a way that protects civil rights and liberties. Texas and Louisiana challenged these guidelines under Article III in federal court. To understand why Texas reacted this way toward the new guidelines, it is essential to note that on January 8, 2021, Texas and DHS agreed and recognized each other’s shared interest in border security. The contract required Texas to “provide information and assistance to help DHS perform its border security, legal immigration, immigration enforcement, and national security missions in exchange for DHS’s commitment to consult… and consider Texas’s views before making immigration policy decisions. These decisions included changes in federal enforcement priorities, staffing, and procedure” (“Immigration…”). Texas also claimed they would have to spend more on law enforcement due to these guidelines. However, the Supreme Court ultimately ruled that Texas and Louisiana lacked Article III standing to challenge DHS’s guidelines. The current issues revolving around immigration in Texas have reached a crisis point, and decisions about who to apprehend those who cross over are locked in at the legal levels.

Spain

Immigration in Spain has been a recurring economic issue, as in the United States. To understand migration flows, it is essential to note the economic difference between the countries of origin and the destination. When discussing the European immigration system, it may be referred to as migration instead. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, migration is “the process of a person or people traveling to a new place or country, usually to find work and live there temporarily or permanently” (“Migration”). In 1992, the Prime Minister of Spain, Felipe González, showed other European heads of state a photograph of Morocco taken from Spanish shores, which contained the caption: “This is our Rio Grande…. It is not far. And living standards are four, five, ten times lower on the other side” (Garcés-Mascareñas 105). The comparison of the river to the Rio Grande already demonstrates the similarities between immigration controversies in different countries. Like in the United States, non-European immigrant workers occupied jobs that local workers avoided. Between 1985 and 2000, the number of legal foreign residents in Spain went from 250,000 to almost 900,000 (Garcés-Mascareñas 112). Migration policies before the 1970s were more concerned with keeping count of the number of emigrants or people who leave their country.

Therefore, throughout the nineteenth century and a part of the twentieth, Spain was attentive to filtering the exit of individuals instead of impeding the entry of individuals from the outside. Garcés-Mascareñas states, “From the 1850s until the 1930s, a series of laws were promulgated to restrict the exit of younger age groups. In the case of men, the measures were intended to ensure there would be enough able-bodied recruits of military age in case of war. As for women, the main argument was that of curbing trafficking in women and, more generally, prostitution of Spanish women in Latin America” (115). Immigration policies were vague and lacked relevance since Spain suffered an emigration crisis where almost 40,000 individuals emigrated illegally to the Americas during the 1910s.

Moreover, the first legal immigration policies were not meant to distinguish between nationals and foreigners. Spain considered individuals from former Spanish colonies except Morocco separate from ‘the rest’ of the individuals who were immigrating there. Therefore, foreigners from Latin America and the Philippines could benefit from the same working rights as Spanish citizens after 1969, even without a work permit. “The Citizenship Law is also a good example of this kind of distinction. Still in force today, the law concedes citizenship after two years of legal residence to people from Latin America, the Philippines and Sephardic Jews, and ten years of legal residence for other foreigners” (Garcés-Mascareñas 117). Stable and intricate immigration policies weren’t created until the end of the Franco dictatorship in 1975. As Garcés-Mascareñas states, “First, the fledgling democracy immediately ratified the main international human rights treaties, for example, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the European Convention on Human rights (1950). Second, the new Constitution (1978) introduced basic matters for the future development of immigration policy as the principle of legal reservation (the obligation to regulate the matter at hand using the Ley de Cortes, the basic law regulating Parliament’s functioning) and the possibility of both parliamentary and judicial control over all administrative action” (117-118 qtd. in Aja 2006: 18). Spain went through three regularizations in which new laws were created. The Spanish parliament approved several actions, such as the Green Paper, which urged the government to take control of the control and channeling of migratory flows, the struggle against illegal immigration, and reforming the administrative apparatus. New regulations introduced the permanent residence permit and regulated the family reunification right. These regularizations aimed to help individuals who had permits under the old laws obtain new permits under the new rules, decreasing the number of undocumented immigrants. A series of new regulations also sped up procedures for obtaining residence and work permits, while improvements were made regarding renewal and the duration of the permits.

Germany

Compared to Spain, Germany considered itself “not an immigration land” throughout history. However, between 1950 and 1994, approximately 80 percent of the increase in West Germany’s population was due to migration. In 2006, the Federal Statistical Office reported that nearly one-fifth, or 19 percent of the population in Germany had a migration background. Still, this number did not include the approximately 12 million ethnic German refugees and expellees who came to Germany as a result of World War II. Klusmeyer claims, “For decades, German government policy was framed around a portrait of national identity that highlighted the absence of characteristics associated with a presumed opposing type of society” (xiii). During the 1990s, Germany reformed its citizenship law in 1999 and began constructing more proactive policy strategies. A report in 2001 stated that Germany needed immigrants, which led to the President of the Bundestag’s recognition that Germany is, in fact, a country of immigration. “The Basic Law of 1949 established the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) as a liberal-democratic polity that is subject to the rule of law” (Klusmeyer 1). This constitution establishes a supreme, authoritative set of norms for the new political and legal order the framers intended to construct. The basic law of Germany is essential to understand its immigration policies. The writers included the list of fundamental rights at the beginning of their constitution rather than the end to display their importance. “Article 1 of the Basic Law provides, 1) The dignity of man shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority. 2) The German people therefore acknowledge invaluable and inalienable human rights as the basis of every community, of peace, and of justice in the world. 3) The following basic rights shall bind the legislature, the executive and the judiciary as directly enforceable law” (Klusmeyer 3). It is similar to the preambles in the United Nations Convention of 1945 and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Over the centuries, Germany created many immigration policies and suffered several changes due to World War II.

Focusing on the twenty-first century, Germany has reformed previous policies and created new ones. Companies asked the government for help, allowing foreigners to come work and fill thousands of vacant positions. They argued this was necessary because domestic workers lacked the training and qualifications for these jobs, so Klusmeyer writes, “In response, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder proposed on 13 March 2000 a plan to provide for the expedited issuance of as many as 20,000 temporary work permits valid for five years. To address the concerns of domestic workers over job competition with foreigners, he announced that the government would spend an additional DM 200 million on domestic training and retraining programs” and, “At the same time, the Chancellor reported that by 2003, German industrial groups were pledging to double the number of apprenticeships available for young Germans joining the work-force” (229-230). The plans for the German Green Card program continued, and they would allow workers to work for five years with the ability of one extension for up to another five years. The program went into effect on August 1, 2000, but was ultimately a failure because many restrictions on the program frustrated both employees and employers, resulting in only 17,831 individuals who came to Germany through the program.

Furthermore, Germany faced many obstacles and restrictions when developing new policies. This all eventually led to the Migration Law of 2005. Klusmeyer describes, “Institutionally, the law restructures the organization of migration and centers all migration-policy in the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), as had been recommended by the Independent Commission. The law also adopted the Commission’s recommendations about a combined work and residence permit; an individual’s work status is now stated on the combined permit. Consolidating two permits into one has created what the German government calls ‘one-stop government.’ Legally resident foreigners now only have to interact with their respective foreigners’ office” (258). Every non-temporary resident either has a permanent or limited-term residence permit since the number of types of non-temporary residence permits has decreased from five to two. EU nationals no longer have to apply for a residence permit. The law provided three new exceptions to the ban on immigration. Highly qualified workers are allowed to immigrate to Germany and are eligible for permanent residence permits. Foreign students who complete university studies can remain in Germany for up to one year to find employment. If investors invest at least one million Euros and create ten new jobs in Germany, they will receive a limited residence permit.

United Kingdom

Immigration policy has developed over one hundred years. It has often been in response to the movements of racialized groups who were perceived as culturally different. The empire has shaped the history of Britain, particularly the withdrawal of rights to UK citizenship and residence in the UK for many non-White subjects as the empire ended. Ireland is a significant source of immigration but is not subject to modern migration controls. After World War II, the UK began seeing massive waves of immigration due to Poland’s role in the Allied resistance, which led to approximately 200,000 soldiers settling in Scotland and London. The European Volunteer Workers Scheme enlisted large numbers of Europeans displaced by the war to move to the UK and assist in rebuilding.

Furthermore, “The British Nationality Act of 1948 provided the first definition of British citizenship and established the same rights for British-born and colonial-born people as a ‘Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies’ (CUKC or ‘British citizen’)” (Shankley and Byrne 37). The Immigration Acts of 1999 and 2002 further narrowed the rights of asylum seekers by removing their benefits and housing rights. It integrated the appeals process, making it illegal to be an undocumented migrant in the UK without a reasonable explanation. Moving along to contemporary immigration policies, Shankley and Byrne outline the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016, “1) To restrict the number of migrants who can enter Britain by reducing the number of channels and visas available that migrants can use to apply to enter the country; 2) To change immigration policies and place the responsibility of checking a person’s immigration status in-house within the housing sector, labour market and education system; 3) To make it easier for the government to remove people who violate immigration rules; and 4) To reduce the mechanisms that are available to people to contest and appeal against immigration violations” (42). These new policies limit work visas and introduce stricter criteria for eligibility to stay in the UK permanently. The acts also impose restrictions on the student visa system, limiting the number of hours international students can work and ending the post-study work entitlement of international students. These acts have created a ‘hostile environment’ because it has led to ethnic discrimination. This is because of the in-house requirements that allow landlords and employers to check the immigration statuses of individuals. The UK places steep fines on those who fail to check the statuses of their tenants or employees. Landlords increasingly target ethnic minority tenants and demand their citizenship and immigration documents to comply with the acts. The Immigration Compliance and Enforcement Team (ICE) activities have also significantly increased.

Conclusion

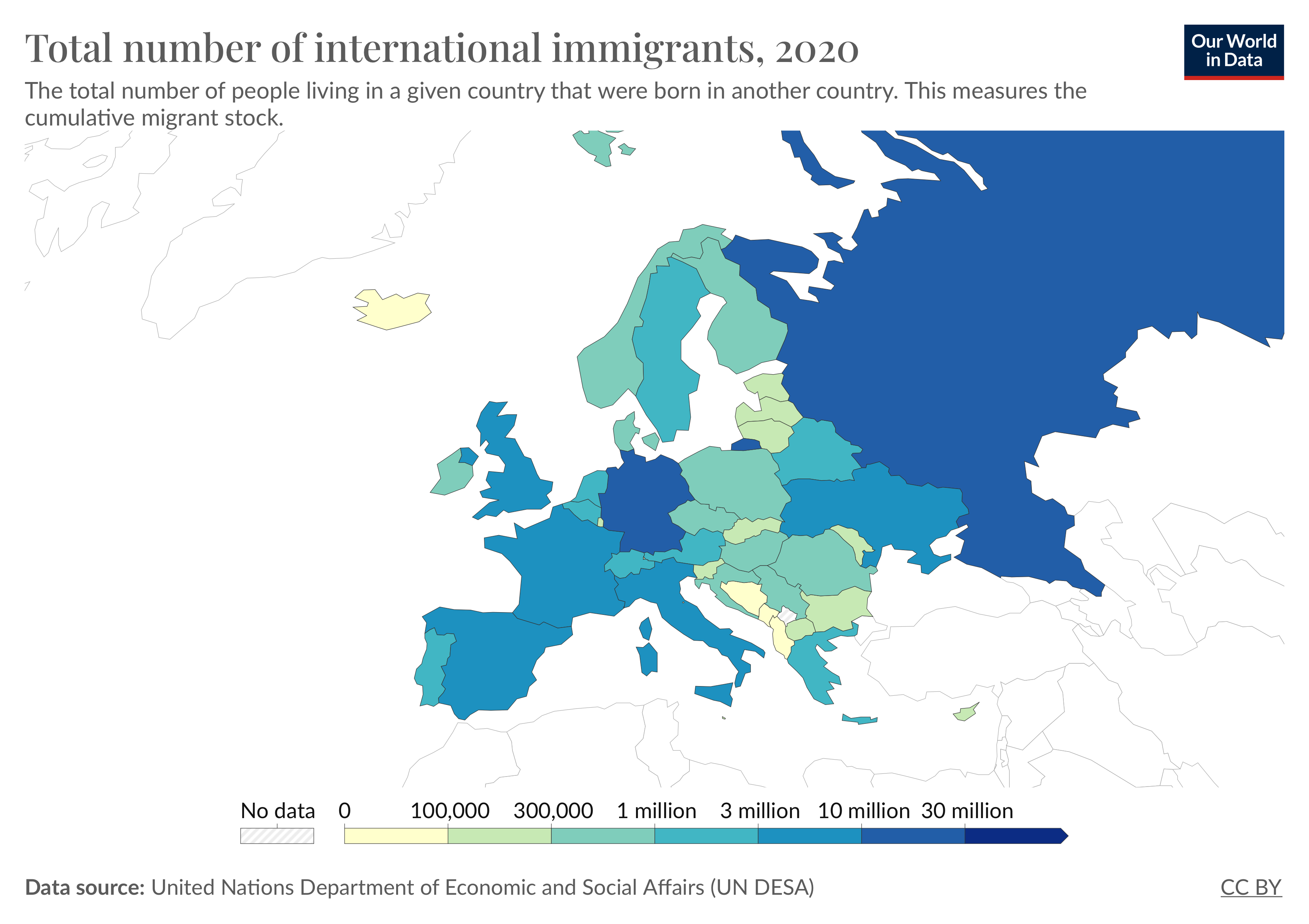

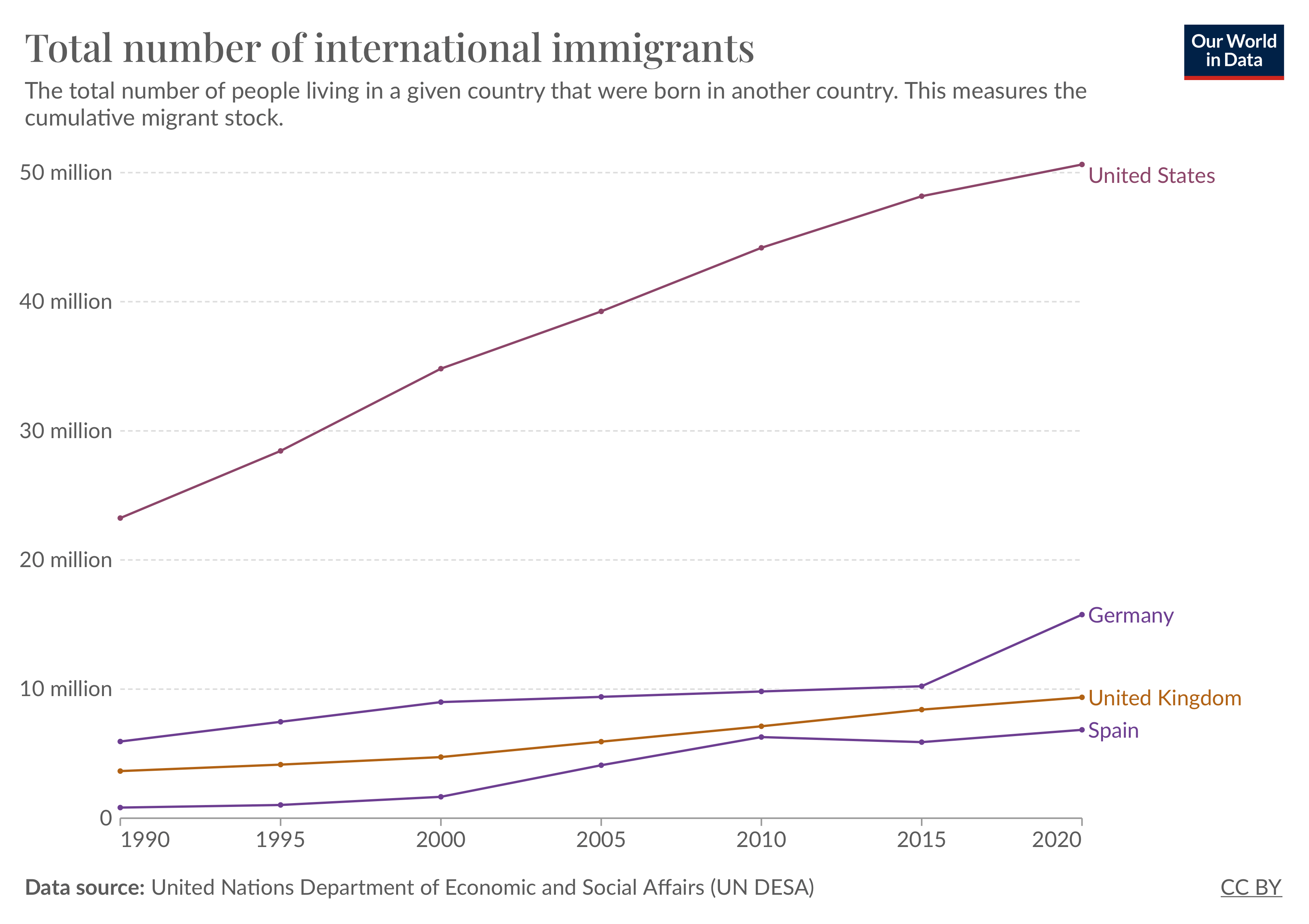

The United States’ immigration system needs to be reformed or improved, and by analyzing Spain, Germany, and the United Kingdom, we can see some ideas and procedures that could be applied to the current system. Therefore, the United States could eventually alleviate the immigration issue that is occurring now. However, a counterargument may be raised that European countries do not deal with the same number of immigrants as the United States. According to the research, it is notable that each country faced an immigration crisis in one way or another. First, Spain experienced an issue with emigration, but later on, the country began to have a surplus of immigrants. Germany struggled to attract immigrants and recognized their importance to the economic growth and innovative impacts that the country needed. The United Kingdom is in a similar position to the United States, struggling to control the number of immigrants coming to their country. They have implemented stricter laws, much like the United States has. European countries are significantly smaller than the United States, so they will most likely never have the same number of immigrants. Still, it is essential to compare the number to the size of the country.

Furthermore, in terms of applying European policies to the United States, Spain played a key role because they were quickly trying to decrease the number of undocumented immigrants. By allowing citizens to be naturalized after ten years of legal residence, they increased their number of citizens. If the United States granted citizenship to legal residents after ten years, it would be a relief and allow more resident permits to be distributed. The United States could also go as far as to grant residency if an individual has been here for ten years or more illegally under certain conditions. This would heavily alleviate the number of undocumented persons. The United States already has a Ten-Year Law in place in which an individual may apply for cancellation of removal, meaning they cannot be deported. They must meet specific requirements such as having been physically present in the United States for at least ten years, maintaining good moral character during the entire period of their stay in the country, not having been convicted of a criminal offense, and having family members who are citizens or permanent residents whose deportation would cause extreme hardship (Berkowsky). Like Germany, the United States could allow students to remain here for up to one year until they can find work. The United States could also provide funding to train domestic workers, like Germany has previously done, to assist its current citizens. Highly qualified workers should also be qualified for a permanent resident permit instead of a limited permit.

Moreover, if the United States wishes to proceed with stricter policies, then it should implement some of the United Kingdom’s procedures. For example, requiring tenants or employers to keep up with immigration statuses is an option, but it leaves the door open for discrimination and other issues. On the other hand, Germany and Spain’s policies are more open and less restrictive, so their models may be more beneficial in the long run. It is essential to understand the criminalization of immigrants in other countries as well as to have a different perspective on the crisis occurring now in the United States. Hateful and divisive immigration rhetoric has become a staple for the United States, but countries overseas do not have the same level of immigration hatred. European countries view immigrants as people who may benefit their society and are treated humanely, which is something the United States should apply to its perspective on immigration. The United States still has a long way to go in immigration reform, but researching other countries may be a step in the right direction if applied beneficially.

References

Berkowsky, Juan. “Can I Fix Papers If I Have 10 Years in the USA?” Marietta Immigration Lawyer, 19 Feb. 2024, urbinalawfirm.com/en/10-year-law-usa/#:~:text=To%20cancel%20your%20deportation%20through,of%20stay%20in%20the%20country.

Garcés-Mascareñas, Blanca. “Spain.” Labour Migration in Malaysia and Spain: Markets, Citizenship and Rights. Amsterdam University Press, 2012, pp. 105–76. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n12v.8. Accessed 2 Mar. 2024.

“Guidelines for the Enforcement of Civil Immigration Law,” www.ice.gov/doclib/news/guidelines-civilimmigrationlaw.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr. 2024.

“Immigration Definition & Meaning.” Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/immigration. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

“Immigration – National Security – State Standing – United States v. Texas.” Harvard Law Review, vol. 137, no. 1, Nov. 2023, pp. 350–59. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=6bf3c6b1-f563-3406-a19d-ffadaecba221.

Klusmeyer, Douglas B. Immigration Policy in the Federal Republic of Germany : Negotiating Membership and Remaking the Nation / Douglas B. Klusmeyer and Demetrios G. Papademetriou. Berghahn Books, 2009. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=07477a2a-da01-35b8-b5c6-d301cf130261.

“Migration | English Meaning – Cambridge Dictionary.” “Migration,” Cambridge University Press, dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/migration. Accessed 30 Apr. 2024.

“Refugees and Asylum.” USCIS, 12 Nov. 2015, www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-asylum.

Scheid, Lauren. “Immigrants Make America Great: Contemporary Overview of the Executive Authority for Regulation of U.S. Immigration Policy.” Indiana International & Comparative Law Review, vol. 30, no. 3, Jan. 2020, pp. 525–36. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=1e63b47d-da8a-3cec-9294-b033d82600d3.

Shankley, William, and Bridget Byrne. “Citizen Rights and Immigration.” Ethnicity and Race in the UK: State of the Nation, edited by William Shankley et al., 1st ed., Bristol University Press, 2020, pp. 35–50. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv14t47tm.8. Accessed 27 Feb. 2024.

4 comments

Nicholas Pigott

Hi Julissa! This is such a great article on an extremely difficult subject. Borders are such a tricky topic, but I’m sure a bipartisan conclusion can come forward that gives both reasonable security and a human centered focus on immigration. We should be secure, but we need empathy for the immigrants coming to our country to seek a better life for their families. The hateful rhetoric of immigrants needs to end, and we must look towards countries on how to combat hateful rhetoric. Great work!

Silvia Benavides

Wow! This article was truly enlightening. It went in-depth and showed the specifics of immigration and its policies. I enjoyed the graphs that were provided. Wonderful Job!

Mariana Chamorro

Julissa, your publication does an excellent job of comparing immigration issues in the United States with those in Europe. I like how you explore historical backgrounds, policy changes, and the current struggles immigrants face in both regions. Your suggestions for improving the U.S. immigration system by learning from Spain, Germany, and the United Kingdom are insightful! Great job

Rhys Williams

I found your discussion on the impact of media exposure on young children both enlightening and thought-provoking. The quote from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) regarding the harmful effects of media exposure on children under two years old underscores the importance of considering the potential consequences of early media consumption on cognitive development and social skills.