The environment we inhabit has drastically changed with the expansion of media devices, but how these new distractions affect us cognitively may be startling. One of the most commonly diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders in children is Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Children who are diagnosed with ADHD may have trouble maintaining their attention, squirm or fidget, have difficulty controlling impulses, daydream frequently, forget or lose things frequently, make careless mistakes, talk too much, or have trouble getting along with others.1 There are three types of ADHD, Predominantly Inattentive Presentation, Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation, or Combined Presentation.1 These three types are the result of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM IV) combining Attention Deficit Disorder and ADHD into one disorder with these three subtypes.3 Predominantly Inattentive is where the individual finds it difficult to maintain their attention long enough to finish a task, pay attention to details, or follow instructions. Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive is where the individual finds it difficult to remain still for extended periods of time and talks frequently. Combined is where both previously mentioned types are present in the individual.1 There are several causes of ADHD, including genetics, brain injury, environmental risks, alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy, premature delivery, and low birth weight.1 Typically, to be labeled as “ADHD,” one must present with symptoms before the age of 12, and the symptoms must be present in multiple locations.3 Our environment has seen drastic changes in recent years with expanding access to media devices such as TVs, tablets, and smartphones. This article aims to explore how the expansion of media has influenced the rise in ADHD diagnoses over the last two decades.

Popular social media apps, such as Facebook and Instagram, have been downloaded by a large portion of the North American population. There are over 220 million users according to the released information from Business of Apps, with the majority of users in the age ranges of 18-24 (30%) and 25-34 (33%).78 According to a study conducted in 2018, the median age for first-time usage of a mobile device (tablet or phone) was 12 months.9 Additionally, they found a positive correlation between age and mobile device access, while the parents of children who owned a mobile device noticed a decrease in family time and interactions.9 Another study conducted in 2014 displayed similar results in an urban, low-income, minority community. Approximately 96.6% of all children in the study used a mobile device, and most owned their own by four years old.11 Parents often give their children a device when doing house chores, at bedtime, or to keep them calm.11 With children getting access to mobile devices that have access to social media apps like Instagram, Facebook, and especially YouTube for younger children, this environment might facilitate the formation of ADHD symptoms.

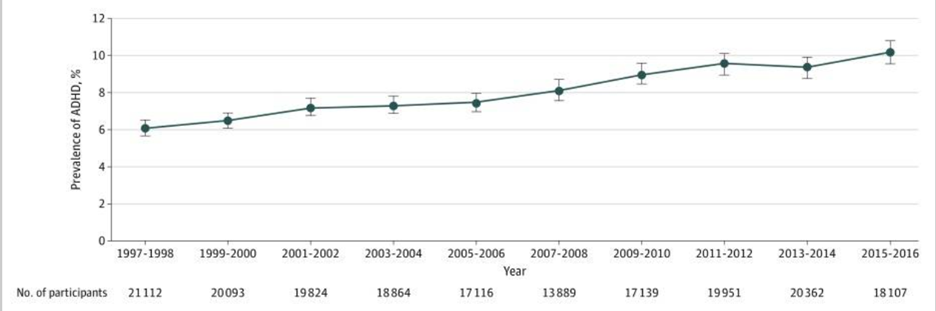

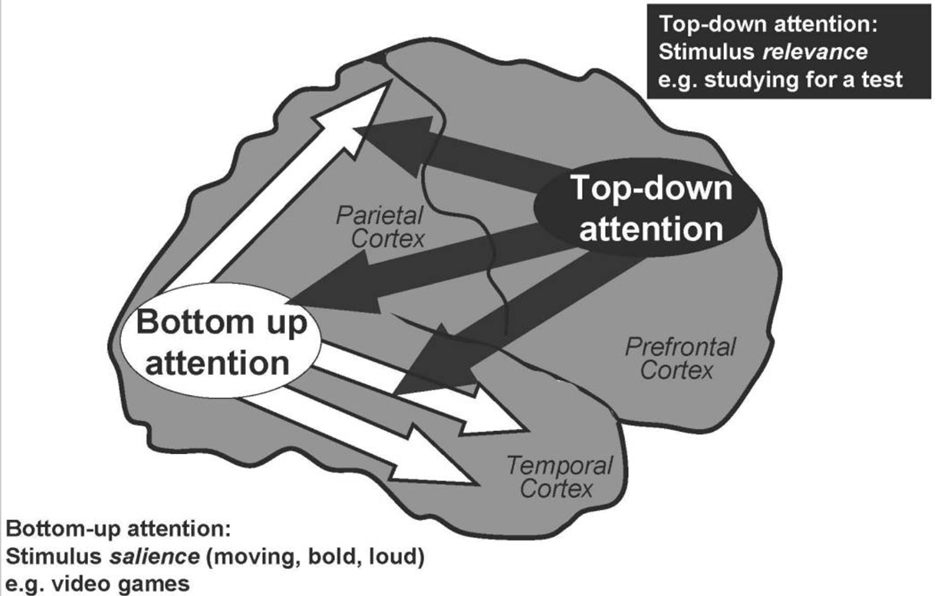

The continual rise in diagnoses of ADHD and data showing how media alters the neurophysiology of the brain should give urgency to this issue. The prevalence of ADHD has almost doubled from 1997 to 2016, with the prevalence of ADHD in 1997-1998 at 6.1% and in 2015-2016 at 10.2%.13 The prevalence more than doubled in girls jumping from 3.1% to 6.3%, while boys had an increase from 9.0% to 14.0%.13 The largest age group increase was in the 12-17 years old group, increasing from 7.2% to 13.5%.13 More recently, a study was performed among children diagnosed with ADHD to see if problematic digital media use worsened the symptoms of ADHD. This study found that children with both ADHD and problematic digital media use suffered from more severe symptoms than those who have ADHD and no problematic usage.16 Figure 1 displays the nearly 60% increase in ADHD prevalence over the two-decade-long span from 1997-2016. This increase, in conjunction with an increase in digital media access in households, makes it seem like the two are linked in some capacity to exacerbate symptoms or facilitate the acquisition of symptoms from somebody who was not diagnosed. There are other reasons why this trend has been upward over the last two decades that are not related to social media. One major way is awareness of ADHD in the public and healthcare. Much like testing for things like COVID or the flu, the more healthcare providers are looking into ADHD, the more likely they will diagnose somebody, even if their symptoms are mild. Things have changed drastically since 2016, which was the last year in the two-decade analysis. Not only the pandemic, which left many people seeking distractions in media and mobile devices, but the prevalence of mobile devices has increased since 2016. In 2016, 114 million iPhone units were active in the United States but increased to 149 million in 2022, according to Business of Apps.17 Spending time on the internet can be a source of entertainment, but after continual use, it can become an addiction. In drug addiction, a spike of dopamine is observed during intoxication, and while off the drug a significant reduction in dopamine is observed, resulting in withdrawals.18 Much like an addiction, it becomes difficult to resist coming back to use it. To determine how media is changing brain health, we can look to imaging.

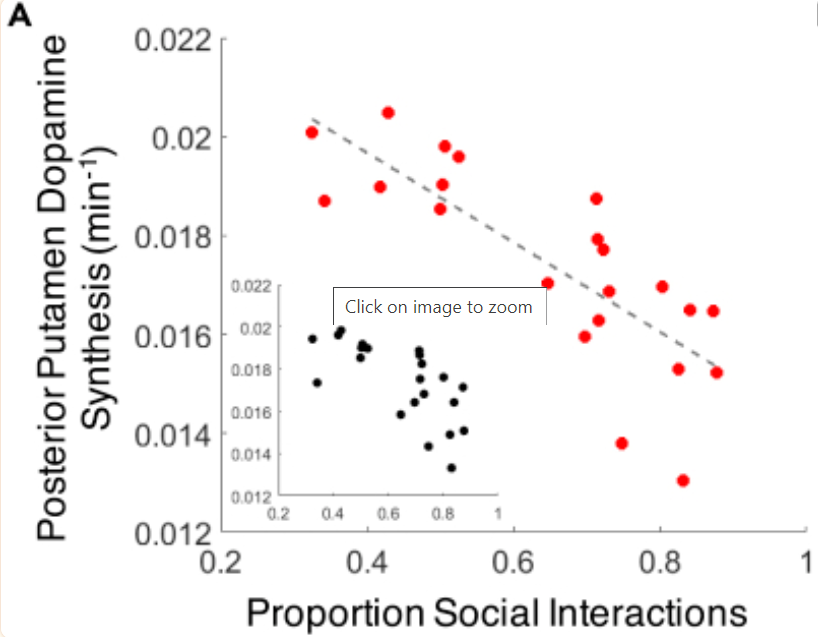

One of the last pieces of evidence that links excessive media usage to ADHD symptoms is the interaction between social media and dopamine. Research has shown ADHD patients have a genetic dysfunction with the “brain reward cascade,” which results in a hypo-dopaminergic trait.30 This leads the patient to exhibit “drug seeking behaviors” to find something (drugs or an activity) to increase dopamine levels.30 This trait is genetic in ADHD patients, but excessive use of media can result in a similar non-genetic effect. Increased social app interactions have been found to decrease the dopamine synthesis capacity of striatal dopamine, specifically in the bilateral putamen.32 Figure 2 illustrates the reduction in dopamine synthesis with increased social media usage. This lowered dopamine synthesis could lead to hypo-dopaminergic traits manifesting, resulting in “drug seeking behaviors,” but the drug is social media. Whenever the person is not on social media, they think life is dull or become disinterested, leading them to actively seek it or wait in anticipation for the next interaction. Constantly having access at your fingertips makes it difficult to resist the urge to open the app. Next thing someone knows, they have spent the last thirty minutes to an hour scrolling on social media, which can be debilitating. Media is meant to be flashy and attention grabbing, and one of the reasons why media is effective is due to spikes in dopamine. The more dopamine you get from extended use, your body will adapt by reducing the effect in some way, either by altering the amount of dopamine or the receptors for dopamine. We begin to crave things we know give us increased levels of dopamine, much like those with ADHD. When we are doing things that have little to no effect on the dopamine levels, it leads to low concentration or interest and possibly becoming jittery. Both of these effects on their own are common in most people every once in a while, but the more people get attached to media, the worse the symptoms become. Eventually, the symptoms will become so extreme that they will be indistinguishable from ADHD, resulting in a diagnosis. Media, especially social media, create an easily accessible and legal way to create dopamine spikes and subsequent dips, which can make it difficult to resist, resulting in increased reward seeking.32

There are ways to mitigate these effects in the younger generations and for yourself. Much of the responsibility falls onto the parents in the early stages of a person’s life. Parents should limit the use of mobile devices heavily in their early formative years. There are educational videos that many parents like to put on for their children, but kids have extreme reactions to their favorite activities being withheld. Setting strict boundaries with the mobile device and the child can help with their expectations, reducing their urges and strain on the right frontal cortex. Creating discipline with media and mobile devices promotes good habits for children and extends to adulthood. The greatest weapon against media is discipline, and as adults, that is truly the best way to prevent yourself from getting sucked into the digital space short of deleting the app or not owning a smartphone. Digital media is diffused throughout modern life and moderating its use could help with mental and physical health.

- CDC. (2021, January 26). What is ADHD? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- CDC. (2021, January 26). What is ADHD? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- Magnus, W., Nazir, S., Anilkumar, A. C., & Shaban, K. (2022). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441838/ ↵

- CDC. (2021, January 26). What is ADHD? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- CDC. (2021, January 26). What is ADHD? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html ↵

- Magnus, W., Nazir, S., Anilkumar, A. C., & Shaban, K. (2022). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441838/ ↵

- Facebook Revenue and Usage Statistics (2023). Business of Apps. Retrieved March 3, 2023, from https://www.businessofapps.com/data/facebook-statistics/ ↵

- Instagram Revenue and Usage Statistics (2023)—Business of Apps. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://www.businessofapps.com/data/instagram-statistics/ ↵

- Kılıç, A. O., Sari, E., Yucel, H., Oğuz, M. M., Polat, E., Acoglu, E. A., & Senel, S. (2019). Exposure to and use of mobile devices in children aged 1–60 months. European Journal of Pediatrics, 178(2), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3284-x ↵

- Kılıç, A. O., Sari, E., Yucel, H., Oğuz, M. M., Polat, E., Acoglu, E. A., & Senel, S. (2019). Exposure to and use of mobile devices in children aged 1–60 months. European Journal of Pediatrics, 178(2), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3284-x ↵

- Kabali, H. K., Irigoyen, M. M., Nunez-Davis, R., Budacki, J. G., Mohanty, S. H., Leister, K. P., & Bonner, R. L., Jr. (2015). Exposure and Use of Mobile Media Devices by Young Children. Pediatrics, 136(6), 1044–1050. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2151 ↵

- Kabali, H. K., Irigoyen, M. M., Nunez-Davis, R., Budacki, J. G., Mohanty, S. H., Leister, K. P., & Bonner, R. L., Jr. (2015). Exposure and Use of Mobile Media Devices by Young Children. Pediatrics, 136(6), 1044–1050. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2151 ↵

- Xu, G., Strathearn, L., Liu, B., Yang, B., & Bao, W. (2018). Twenty-Year Trends in Diagnosed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Among US Children and Adolescents, 1997-2016. JAMA network open, 1(4), e181471. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1471 ↵

- Xu, G., Strathearn, L., Liu, B., Yang, B., & Bao, W. (2018). Twenty-Year Trends in Diagnosed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Among US Children and Adolescents, 1997-2016. JAMA network open, 1(4), e181471. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1471 ↵

- Xu, G., Strathearn, L., Liu, B., Yang, B., & Bao, W. (2018). Twenty-Year Trends in Diagnosed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Among US Children and Adolescents, 1997-2016. JAMA network open, 1(4), e181471. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1471 ↵

- Shuai, L., He, S., Zheng, H., Wang, Z., Qiu, M., Xia, W., Cao, X., Lu, L., & Zhang, J. (2021). Influences of digital media use on children and adolescents with ADHD during COVID-19 pandemic. Globalization and health, 17(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00699-z ↵

- Apple Statistics (2023)—Business of Apps. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://www.businessofapps.com/data/apple-statistics/ ↵

- Volkow, N. D., Fowler, J. S., & Wang, G. J. (2002). Role of dopamine in drug reinforcement and addiction in humans: results from imaging studies. Behavioural pharmacology, 13(5-6), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008877-200209000-00008 ↵

- Xu, G., Strathearn, L., Liu, B., Yang, B., & Bao, W. (2018). Twenty-Year Trends in Diagnosed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Among US Children and Adolescents, 1997-2016. JAMA network open, 1(4), e181471. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1471 ↵

- Moisala, M., Salmela, V., Hietajärvi, L., Salo, E., Carlson, S., Salonen, O., Lonka, K., Hakkarainen, K., Salmela-Aro, K., & Alho, K. (2016). Media multitasking is associated with distractibility and increased prefrontal activity in adolescents and young adults. NeuroImage, 134, 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.011 ↵

- Kaya, E. M., & Elhilali, M. (2014). Investigating bottom-up auditory attention. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00327 ↵

- Arnsten A. F. (2009). The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. The Journal of pediatrics, 154(5), I–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018 ↵

- Arnsten A. F. (2009). The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. The Journal of pediatrics, 154(5), I–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018 ↵

- Arnsten A. F. (2009). The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. The Journal of pediatrics, 154(5), I–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018 ↵

- Arnsten A. F. (2009). The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. The Journal of pediatrics, 154(5), I–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018 ↵

- Arnsten A. F. (2009). The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. The Journal of pediatrics, 154(5), I–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018 ↵

- Firth, J., Torous, J., Stubbs, B., Firth, J. A., Steiner, G. Z., Smith, L., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Gleeson, J., Vancampfort, D., Armitage, C. J., & Sarris, J. (2019). The “online brain”: how the Internet may be changing our cognition. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 18(2), 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20617 ↵

- Arnsten A. F. (2009). The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. The Journal of pediatrics, 154(5), I–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018 ↵

- Arnsten A. F. (2009). The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. The Journal of pediatrics, 154(5), I–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018 ↵

- Blum, K., Chen, A. L., Braverman, E. R., Comings, D. E., Chen, T. J., Arcuri, V., Blum, S. H., Downs, B. W., Waite, R. L., Notaro, A., Lubar, J., Williams, L., Prihoda, T. J., Palomo, T., & Oscar-Berman, M. (2008). Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder and reward deficiency syndrome. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 4(5), 893–918. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s2627 ↵

- Blum, K., Chen, A. L., Braverman, E. R., Comings, D. E., Chen, T. J., Arcuri, V., Blum, S. H., Downs, B. W., Waite, R. L., Notaro, A., Lubar, J., Williams, L., Prihoda, T. J., Palomo, T., & Oscar-Berman, M. (2008). Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder and reward deficiency syndrome. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 4(5), 893–918. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s2627 ↵

- Westbrook, A., Ghosh, A., van den Bosch, R., Määttä, J. I., Hofmans, L., & Cools, R. (2021). Striatal dopamine synthesis capacity reflects smartphone social activity. iScience, 24(5), 102497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102497 ↵

- Westbrook, A., Ghosh, A., van den Bosch, R., Määttä, J. I., Hofmans, L., & Cools, R. (2021). Striatal dopamine synthesis capacity reflects smartphone social activity. iScience, 24(5), 102497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102497 ↵

- Westbrook, A., Ghosh, A., van den Bosch, R., Määttä, J. I., Hofmans, L., & Cools, R. (2021). Striatal dopamine synthesis capacity reflects smartphone social activity. iScience, 24(5), 102497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102497 ↵

- Cardoso-Leite, P., Buchard, A., Tissieres, I., Mussack, D., & Bavelier, D. (2021). Media use, attention, mental health and academic performance among 8 to 12 year old children. PloS one, 16(11), e0259163. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259163 ↵

- Cardoso-Leite, P., Buchard, A., Tissieres, I., Mussack, D., & Bavelier, D. (2021). Media use, attention, mental health and academic performance among 8 to 12 year old children. PloS one, 16(11), e0259163. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259163 ↵

4 comments

Sofia Perez

Hi Jack! I have seen this condition first hand, so I know how badly it can affect someone. I liked that you brought up the anatomy of the brain and explained well the effect it can portray under those with the condition of ADHD. I can agree that the use of media can play a huge part in society’s mental illnesses since it represents many falsehoods.

Carina Martinez

Great job on this article, very well done! It is interesting to learn about the facts of ADHD. congratulations on your nomination.

Guiliana Devora

This is an amazing article and the author who wrote this did an amazing job of telling it! Congratulations as well on the nomination, it was well deserved. As a kid that has 6 siblings and everyone of them has ADHD except for me, I will say I do know a thing or two about it. So reading this article was very insightful for me and I will definitely be sharing it with my parent sand siblings.

Natalia Bustamante

Hi Jack! Firstly, I am really glad you chose to talk about this important topic that has been roaming around for a while now. It is so important to raise awareness on this crucial issue that has been, unfortunately, taking the lives of many individuals who suffer from ADHD. With the rise of social media, the rise of ADHD has gone tremendously high. Parents should see the correlation of social media with the rise of ADHD to control and minimize their child’s ADHD levels. Overall, such a well-written article, Jack. I was really impressed with a lot of the statistics that ADHD has caused.