Influenza is a well-known viral infection that affects the lungs, nose, and throat. Symptoms of the flu include fever, chills, muscle aches, cough, congestion, runny nose, headaches, and fatigue. The flu is prevented by annual flu shots that build up the immune system by using a dead strain of the infection. However, that was not the case in 1918. In 1918, a flu outbreak emerged, killing millions of people wherever it spread. The flu outbreak affected children and adults. By the end of 1920, the number of flu cases began to drop. Although the flu was able to kill millions of people, this apparent strain, the Spanish flu or H1N1, was able to easily kill healthy individuals. It was lethal to healthy adults ages twenty to twenty-four, as opposed to most flu outbreaks, which kill only the very young, the elderly, and people with weakened immune systems.1 At that time, there were claims that there were vaccines that were effective against the flu, which would allow healthy individuals to fight the flu easily. But in this case, these individuals ended up dying easily, adding to the mortality rate. By the end of 1919, the 1918 flu strain quickly disappeared from the human population and was replaced by other, less virulent strains of the virus.2 At the end of the pandemic, questions arose about how healthy individuals succumbed so easily to the flu. Researchers have looked for the answers to how the healthy were so easily affected. Yet the answer seemed to be closer than they thought. This flu outbreak was able to easily kill healthy individuals because the flu strain was not properly identified, which resulted in the wrong vaccine, making healthy individuals more susceptible to the flu.

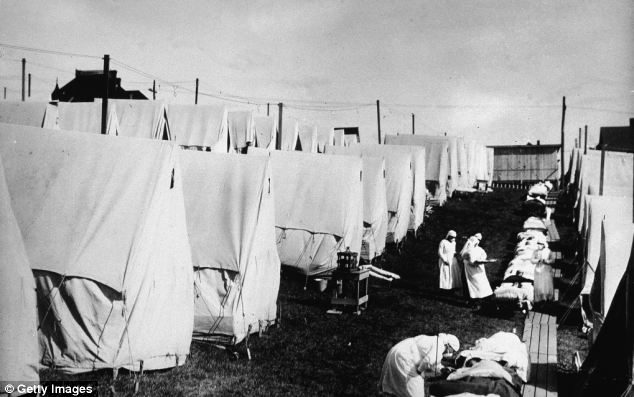

The flu is a contagious respiratory illness that occurs frequently in the winter and early spring. The flu is treatable and can be avoided with an annual flu shot. The flu is identified with the H#N#, in order to set a distinction between different types of flu and its subtypes, like type A flu, examples being the avian flu, H5N1, or swine flu, H2N1. The Spanish flu, or H1N1 strain, began in March of 1918 in Asia. Over the course of two to three months, the flu began to spread from Asia to Europe and to the rest of the world. The 1918 pandemic spread more or less simultaneously in three distinct waves during an approximate twelve-month period in 1918-1919, in Europe, Asia, and North America.3 By the time the flu spread into Asia, the United States, and Europe, between twenty- to forty-million people were killed by the flu, which is more than the number of people who died during WWI.4 The 1918 pandemic virus infected cells in the upper respiratory tract, transmitting easily, but also settling deep in the lungs, damaging tissue and often leading to viral as well as bacterial pneumonia.5 The flu continued to spread, causing hospitals to be overfilled with people infected by the flu. This resulted in hospitals treating patients in schools or other buildings and in tents outside of the hospitals. Near the end of 1919, the spread of the flu began to slow down and people began to recover and return to their normal lives, without the fear of the spread of the flu. Although the pandemic was over, researchers began to question why healthy individuals were easily infected with flu and how were they exposed to the flu. It would take some time before researchers identified the cause of this through a solution that was thought to have prevented the spread of the flu, which was discovered decades later, when technology had improved. Researchers have since learned that the vaccines that were provided in 1918, which were suppose to prevent the spread of the flu and build immunity against it, were ineffective.

Vaccines have been essential in fighting illnesses. They induce an immune response in the body, in order to give the body a fighting chance against a live strain. In 1796, Edward Jenner, a British doctor, created the first successful vaccine to prevent the spread of smallpox. He did this by using a strain from cowpox and scratched it onto a boy. The boy recovered quickly from this. Jenner later exposed the same boy to smallpox, but the boy showed no sign of contracting smallpox. Edward Jenner’s discovery revolutionized medicine because it led to prevention of other illnesses that were thought to be unpreventable. Flu vaccines, in this case, help the body fight back against the flu. They are suggested by doctors because it gives the body some time to build some immunity to the flu, allowing the body to fight back against the flu easily. In order for flu vaccines to work, a dead strain of the virus is used in the vaccine because it allows the body to produce the proper immunoglobulin to fight the flu. Immunoglobulin, often referred to as white blood cells, fight antigens, a foreign substance or toxin that induce an immune response.[6. Peter F. Wright, “How Do Influenza Vaccines Work?,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 39, Volume 39, no. 7 (October 2004): 928–929.] Examples of antigens include bacteria, viruses, and foreign substances in the blood. In the case of the flu, the vaccines protect against three strains of the flu: influenza A (H1N1 and H3N2) and influenza B. In the case of the 1918 pandemic, the vaccines must not have used a dead strain or the flu was not classified as a bacteria. If the vaccines did not use the dead strain, then the amount of people who were infected were increased, which would have increased the mortality rate. It would seem likely in the case of the flu, since the mortality rate was high. But, physicians studied Edward Jenner’s work on vaccine, which would scratch this out. Yet, if the vaccine had the wrong strain, then there would be some protection against other illnesses with that strain. This would be the probable case, since there were some technology that would be useful in identifying the flu strain.

During the pandemic, hospitals were overrun by the sick, soon causing hospitals to reach capacity. This resulted in hospitals creating make-shift treatment areas outside of the hospitals. In order to resolve this issue, researchers decided to look for a cause for the number of people being infected and a possible cure or prevention to the spread of the flu. Researchers theorized that the flu strain had an intrinsically high virulence, tempered only in those patients who had been born before 1889 because of exposure to a then-circulating virus that was capable of providing partial immunoprotection against the 1918 virus strain in people older than 35 years.6 This theory was proven decades later by researchers. In the search for the cure, researchers first assumed that the flu was a bacteria called Bacillus Influenzae, which was discovered by Richard Pfeiffer when he was looking into the lungs of an influenza patient.7 With Pfeiffer’s discovery, the development of the first flu vaccine was underway to deal with the outbreak. When Pfeiffer’s vaccine was released, there was a relief from the medical community because there was a hope that the number of flu patients would decrease. However, that was not the case. People were still coming in with flu symptoms. To make matter’s worse, healthy individuals who had taken the vaccine ended up in hospitals. Decades later, with further analysis and improved technology, scientists began to study why the flu vaccines were ineffective against the flu. They soon discovered that the vaccines from 1918 that were claimed to be effective against the flu, like the Pfeiffer vaccine, contained combinations of different bacterial strains.8 In addition to this discovery, researchers from 1918 did not seem to have properly identified the strain. This would have made the 1918 flu vaccine ineffective in preventing the spread of the flu and building an immunity to the flu strain. Millions of people died from the 1918 Flu Pandemic believing that the flu vaccines would have protected them against the flu.

Although the 1918 flu vaccine was not as effective as it was supposed to be in preventing the spread of infection and building immunity to fight the flu, it did help in the prevention of other illnesses. When Richard Pfeiffer discovered the bacteria that was thought to be the cause of the flu, researchers engineered the vaccine that would have prevented the spread of the flu and build immunity against it. Yet, the vaccines proved ineffective in preventing the spread and building immunity against the flu. But in 2010, an analysis was done over the flu pandemic of 1918. The analysis suggested that the vaccines that were provided reduced the attack rate of pneumonia after viral influenza infection.9 After the flu had run its course in the body, the immune system was strengthened from the fight, thus allowing it to have a temporary build of immunity from the flu until the end of the flu season. In addition, the vaccines would also have a cross protection against other bacteria-related illnesses, like streptococcus. Since the 1918 vaccine contained a strain of bacteria, it would have offered protection and immunity to other bacteria-related illnesses. The vaccines in 1918 may have been a mistake since the flu strain was proven to be not a bacteria, but it has provided more solutions to preventing the spread of bacteria related illnesses. Although the vaccines that were provided in 1918 may not have been effective against the Spanish flu, these vaccines became useful in the prevention of other bacteria-related illnesses.

Vaccines have proven to be useful in preventing illnesses. Although the Flu Pandemic of 1918 continued to kill millions until 1920, it has given insight into how the vaccines should work during flu season. In order for vaccines to be effective, the proper strain of the illness needs to be identified. If the proper strain is not identified, containment of the illness will become impossible, thus leading to more people being infected and spreading uncontrollably. This pandemic must have been a wake up call for researchers, since the flu became uncontrollable and preventing the spread of it would have eased the influx of patients entering the hospitals at that time. If it was not for this pandemic, we would not have the proper flu vaccines that would build immunity against the flu. Decades after the pandemic, flu vaccines have been properly engineered to protect against the flu strain each flu season. But scientists have learned overtime, the flu strain becomes more resistant to treatment each season. The 1918 Flu Pandemic could happen again at some point, if the flu strain is resistant to treatment.

- In Environmental Encyclopedia, 2011, s.v. “Flu Pandemic,” by Angela Woodward. ↵

- Carlo Caduff, The Pandemic Perhaps: Dramatic Events in a Public Culture of Danger (California: University of California Press, 2015), 10. ↵

- Jeffery K. Taubenberger and David M. Morens, “1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 12, no. 1 (January 2006): 15-22. ↵

- Molly Billings, “The 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” Stanford (2005): 1. ↵

- John M. Barry, “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America,” Smithsonian Institution, (November 2017): 1. ↵

- Jeffery K. Taubenberger and David M. Morens, “1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 12, no. 1 (January 2006): 16. ↵

- Karie Youngdahl, “Spanish Influenza Pandemic and Vaccines,” The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (December 2011): 1. ↵

- Darya Nesterova, “Influenza Vaccine History,” Vaccination Research Group (October 2012): 2. ↵

- Karie Youngdahl, “Spanish Influenza Pandemic and Vaccines,” The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (December 2011): 1. ↵

67 comments

Olivia Tijerina

The message that I had grasped is that we have to get through the troubled to get to the right. For it was the doctor themselves that had a piece that had set foot into the direction that was efficient but not effective to the population because numbers of death had still inclined. Much put in the scientist’s approached to fix the pandemic they soon did find a solution that would serve to future generation to come.

Breanna Ortiz

This article was great to read especially since we’re going into flu season. I recently received my flu vaccine at my work site and some of my co workers stated that they were not going to get the flu shot because they were going to get the flu. I feel that having this mindset really does set us back from preventing the spreading of the flu as well as protecting ourselves from it. Just recently many people were passing away from different strains of the flu, this includes children. I think it is important for our children and us to receive the flu vaccine because not everyone has strong immune systems.

Sabrina Doyon

It is truly terrifying that a small mistake such as not labeling the strain correctly can cause such death and destruction. I am so glad that vaccines exist because they have eradicated some of the heartiest of strains. However it is quite easy to have this mistake happen again in the future. I hope this article doesn’t fuel the anti-vax agenda because mistakes are an important part of success. Without this incident people may have continued to make this mistake and more people would die. I think this article does a great job at explaining this event in history without any bias.

Kenneth Gilley

I liked the author’s inclusion of how flu vaccines need to be made in order to be as effective as possible. I agree that we are probably more opposed to vaccination now because we no longer face epidemics like 1918 flu pandemic. It is interesting that the 1918 flu vaccine was not effective at preventing Spanish flu, the target of the vaccine, but it was good at protecting people against other diseases.

Daniel Ramirez

I found this article very interesting. I did not know that the foundation of vaccines against any virus was made of the strain of the dead virus. It is really crazy that some vaccines, such as the case of the Spanish Flu, were not able to protect its recipients from being infected, despite being expected to do so. I also found it interesting that it would prevent people from obtaining any other viruses, despite being less affective to its target virus. Overall, from the article and personal experiences, I believe that vaccines have done tremendous good in protecting the public from an overwhelming epidemic. We continue to learn, just as the viruses do, and the stronger they get, so do we.

Joshua Garza

This is a great article I never knew there was such thing as a flu epidemic. This is a very educating article over the whole epidemic and really shines a light on why my grandma is a lot more adamant about getting the flue shot than me or my mom is because her parents had to go through the epidemic themselves. I’m glad we don’t have to deal with that today.

Mariah Cavanaugh

This was a great article and the well timed also! I believe that one of the reasons so many of our generation has become stanchly opposed to vaccines is because we are so far removed from health epidemics such as the Flu and Polio. We weren’t around to see the death toll rise into the millions from these diseases that are now preventable thanks to vaccines.

Mia Morales

This article is significant, especially when there are many people today that choose not to vaccinate their children. There was a lot of information on this article that I was not aware of, such as the history of how vaccine was created to end this deadly epidemic. I also was unaware of the number of people that died because of this disease.

Jose Fernandez

This article is very interesting, and it contains a lot of important information. I think the author did a great job organizing this information and making the article easy to read. It is amazing how diseases like this flu were a huge problem for people. It makes me feel grateful for the time I live in. I really enjoyed the part where the creation of the vaccine is explained. Great article!

Gabrien Gregory

One leading point of information or thought I took from this is the importance of public health networks and education on health. When a new virus breaks out in the world today, the World Health Organization and the CDC and their partners work to mitigate spreads, find the source and a cure. It is hard to imagine such a failure of vaccination, but this experience clearly served as a learning curb to those in the medical field for future strains and viruses. My only critique of this article would be that it seemed to be more of an article about vaccines at times rather than a focus on the 1918 outbreak. Overall, I really enjoyed this thought-provoking read on a topic I do not know much about. -Reposted from Sep 26 on WP