Influenza is a well-known viral infection that affects the lungs, nose, and throat. Symptoms of the flu include fever, chills, muscle aches, cough, congestion, runny nose, headaches, and fatigue. The flu is prevented by annual flu shots that build up the immune system by using a dead strain of the infection. However, that was not the case in 1918. In 1918, a flu outbreak emerged, killing millions of people wherever it spread. The flu outbreak affected children and adults. By the end of 1920, the number of flu cases began to drop. Although the flu was able to kill millions of people, this apparent strain, the Spanish flu or H1N1, was able to easily kill healthy individuals. It was lethal to healthy adults ages twenty to twenty-four, as opposed to most flu outbreaks, which kill only the very young, the elderly, and people with weakened immune systems.1 At that time, there were claims that there were vaccines that were effective against the flu, which would allow healthy individuals to fight the flu easily. But in this case, these individuals ended up dying easily, adding to the mortality rate. By the end of 1919, the 1918 flu strain quickly disappeared from the human population and was replaced by other, less virulent strains of the virus.2 At the end of the pandemic, questions arose about how healthy individuals succumbed so easily to the flu. Researchers have looked for the answers to how the healthy were so easily affected. Yet the answer seemed to be closer than they thought. This flu outbreak was able to easily kill healthy individuals because the flu strain was not properly identified, which resulted in the wrong vaccine, making healthy individuals more susceptible to the flu.

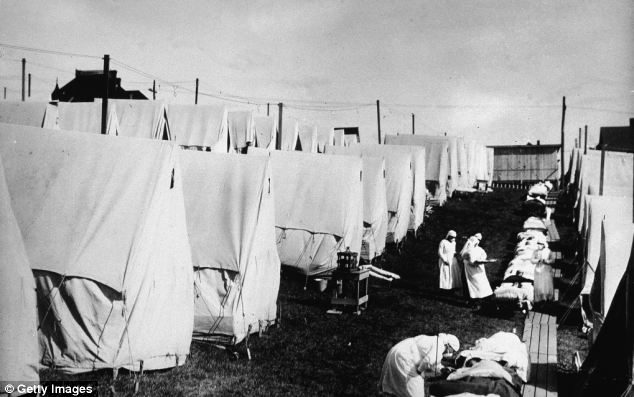

The flu is a contagious respiratory illness that occurs frequently in the winter and early spring. The flu is treatable and can be avoided with an annual flu shot. The flu is identified with the H#N#, in order to set a distinction between different types of flu and its subtypes, like type A flu, examples being the avian flu, H5N1, or swine flu, H2N1. The Spanish flu, or H1N1 strain, began in March of 1918 in Asia. Over the course of two to three months, the flu began to spread from Asia to Europe and to the rest of the world. The 1918 pandemic spread more or less simultaneously in three distinct waves during an approximate twelve-month period in 1918-1919, in Europe, Asia, and North America.3 By the time the flu spread into Asia, the United States, and Europe, between twenty- to forty-million people were killed by the flu, which is more than the number of people who died during WWI.4 The 1918 pandemic virus infected cells in the upper respiratory tract, transmitting easily, but also settling deep in the lungs, damaging tissue and often leading to viral as well as bacterial pneumonia.5 The flu continued to spread, causing hospitals to be overfilled with people infected by the flu. This resulted in hospitals treating patients in schools or other buildings and in tents outside of the hospitals. Near the end of 1919, the spread of the flu began to slow down and people began to recover and return to their normal lives, without the fear of the spread of the flu. Although the pandemic was over, researchers began to question why healthy individuals were easily infected with flu and how were they exposed to the flu. It would take some time before researchers identified the cause of this through a solution that was thought to have prevented the spread of the flu, which was discovered decades later, when technology had improved. Researchers have since learned that the vaccines that were provided in 1918, which were suppose to prevent the spread of the flu and build immunity against it, were ineffective.

Vaccines have been essential in fighting illnesses. They induce an immune response in the body, in order to give the body a fighting chance against a live strain. In 1796, Edward Jenner, a British doctor, created the first successful vaccine to prevent the spread of smallpox. He did this by using a strain from cowpox and scratched it onto a boy. The boy recovered quickly from this. Jenner later exposed the same boy to smallpox, but the boy showed no sign of contracting smallpox. Edward Jenner’s discovery revolutionized medicine because it led to prevention of other illnesses that were thought to be unpreventable. Flu vaccines, in this case, help the body fight back against the flu. They are suggested by doctors because it gives the body some time to build some immunity to the flu, allowing the body to fight back against the flu easily. In order for flu vaccines to work, a dead strain of the virus is used in the vaccine because it allows the body to produce the proper immunoglobulin to fight the flu. Immunoglobulin, often referred to as white blood cells, fight antigens, a foreign substance or toxin that induce an immune response.[6. Peter F. Wright, “How Do Influenza Vaccines Work?,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 39, Volume 39, no. 7 (October 2004): 928–929.] Examples of antigens include bacteria, viruses, and foreign substances in the blood. In the case of the flu, the vaccines protect against three strains of the flu: influenza A (H1N1 and H3N2) and influenza B. In the case of the 1918 pandemic, the vaccines must not have used a dead strain or the flu was not classified as a bacteria. If the vaccines did not use the dead strain, then the amount of people who were infected were increased, which would have increased the mortality rate. It would seem likely in the case of the flu, since the mortality rate was high. But, physicians studied Edward Jenner’s work on vaccine, which would scratch this out. Yet, if the vaccine had the wrong strain, then there would be some protection against other illnesses with that strain. This would be the probable case, since there were some technology that would be useful in identifying the flu strain.

During the pandemic, hospitals were overrun by the sick, soon causing hospitals to reach capacity. This resulted in hospitals creating make-shift treatment areas outside of the hospitals. In order to resolve this issue, researchers decided to look for a cause for the number of people being infected and a possible cure or prevention to the spread of the flu. Researchers theorized that the flu strain had an intrinsically high virulence, tempered only in those patients who had been born before 1889 because of exposure to a then-circulating virus that was capable of providing partial immunoprotection against the 1918 virus strain in people older than 35 years.6 This theory was proven decades later by researchers. In the search for the cure, researchers first assumed that the flu was a bacteria called Bacillus Influenzae, which was discovered by Richard Pfeiffer when he was looking into the lungs of an influenza patient.7 With Pfeiffer’s discovery, the development of the first flu vaccine was underway to deal with the outbreak. When Pfeiffer’s vaccine was released, there was a relief from the medical community because there was a hope that the number of flu patients would decrease. However, that was not the case. People were still coming in with flu symptoms. To make matter’s worse, healthy individuals who had taken the vaccine ended up in hospitals. Decades later, with further analysis and improved technology, scientists began to study why the flu vaccines were ineffective against the flu. They soon discovered that the vaccines from 1918 that were claimed to be effective against the flu, like the Pfeiffer vaccine, contained combinations of different bacterial strains.8 In addition to this discovery, researchers from 1918 did not seem to have properly identified the strain. This would have made the 1918 flu vaccine ineffective in preventing the spread of the flu and building an immunity to the flu strain. Millions of people died from the 1918 Flu Pandemic believing that the flu vaccines would have protected them against the flu.

Although the 1918 flu vaccine was not as effective as it was supposed to be in preventing the spread of infection and building immunity to fight the flu, it did help in the prevention of other illnesses. When Richard Pfeiffer discovered the bacteria that was thought to be the cause of the flu, researchers engineered the vaccine that would have prevented the spread of the flu and build immunity against it. Yet, the vaccines proved ineffective in preventing the spread and building immunity against the flu. But in 2010, an analysis was done over the flu pandemic of 1918. The analysis suggested that the vaccines that were provided reduced the attack rate of pneumonia after viral influenza infection.9 After the flu had run its course in the body, the immune system was strengthened from the fight, thus allowing it to have a temporary build of immunity from the flu until the end of the flu season. In addition, the vaccines would also have a cross protection against other bacteria-related illnesses, like streptococcus. Since the 1918 vaccine contained a strain of bacteria, it would have offered protection and immunity to other bacteria-related illnesses. The vaccines in 1918 may have been a mistake since the flu strain was proven to be not a bacteria, but it has provided more solutions to preventing the spread of bacteria related illnesses. Although the vaccines that were provided in 1918 may not have been effective against the Spanish flu, these vaccines became useful in the prevention of other bacteria-related illnesses.

Vaccines have proven to be useful in preventing illnesses. Although the Flu Pandemic of 1918 continued to kill millions until 1920, it has given insight into how the vaccines should work during flu season. In order for vaccines to be effective, the proper strain of the illness needs to be identified. If the proper strain is not identified, containment of the illness will become impossible, thus leading to more people being infected and spreading uncontrollably. This pandemic must have been a wake up call for researchers, since the flu became uncontrollable and preventing the spread of it would have eased the influx of patients entering the hospitals at that time. If it was not for this pandemic, we would not have the proper flu vaccines that would build immunity against the flu. Decades after the pandemic, flu vaccines have been properly engineered to protect against the flu strain each flu season. But scientists have learned overtime, the flu strain becomes more resistant to treatment each season. The 1918 Flu Pandemic could happen again at some point, if the flu strain is resistant to treatment.

- In Environmental Encyclopedia, 2011, s.v. “Flu Pandemic,” by Angela Woodward. ↵

- Carlo Caduff, The Pandemic Perhaps: Dramatic Events in a Public Culture of Danger (California: University of California Press, 2015), 10. ↵

- Jeffery K. Taubenberger and David M. Morens, “1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 12, no. 1 (January 2006): 15-22. ↵

- Molly Billings, “The 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” Stanford (2005): 1. ↵

- John M. Barry, “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America,” Smithsonian Institution, (November 2017): 1. ↵

- Jeffery K. Taubenberger and David M. Morens, “1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 12, no. 1 (January 2006): 16. ↵

- Karie Youngdahl, “Spanish Influenza Pandemic and Vaccines,” The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (December 2011): 1. ↵

- Darya Nesterova, “Influenza Vaccine History,” Vaccination Research Group (October 2012): 2. ↵

- Karie Youngdahl, “Spanish Influenza Pandemic and Vaccines,” The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (December 2011): 1. ↵

67 comments

Lamont Traylor

It’s crazy to imagine that millions of people died from the flu when people didn’t really know about it or how to deal with it and then even after the vaccine, people still die from the flu. The flu is such a dangerous virus and I’ve almost died from it myself, luckily, I didn’t. I’m just very grateful that people worked on a cure and found one, or else life would be awful.

Rylie Kieny

Everyone has heard of or had the flu in recent years. However I was not aware that the flu vaccine of 1918 is was caused the death of millions. Many people are unaware of how vaccines work but this article did a good job in explaining the preciseness needed in order for the vaccines to be effective. It also tells the experience and knowledge researchers must have in creating the perfect vaccine. It is scary to know that as years go on the strain will become more resistant to the vaccines and a possible outbreak could occur.

Mariah Cavanaugh

I was not aware of the fact that part of what contributed to the death toll was the vaccine itself. Your fit all of the critical information into your article regarding the outbreak, death toll, and vaccines. However, I think that your story would benefit from a little more editing. The typos and formatting errors were distracting and took away from the flow of the story.

Brianna Ford

I did not know that back then influenza was killing that many people. It’s very unfortunate that even the antibiotic was killing the healthiest people. It’s almost like they would have been better off with out the antibiotic. I’m just glad we have came along way and our treatments are now effective. In my opinion, this article was very heavy with information. There wasn’t really a story, just more of a informative essay on influenza, however overall a good article.

Harashang Gajjar

The flu took a heavy human toll, wiping out entire families and leaving countless widows and orphans in its wake. Funeral parlors were overwhelmed and bodies piled up. Many people had to dig graves for their own family members.The flu was also detrimental to the economy. In the United States, businesses were forced to shut down because so many employees were sick. Basic services such as mail delivery and garbage collection were hindered due to flu-stricken workers.

kendrick Harrison

No offense to the Author (Michael Thomas), but the article seemed to drag on a bit in the first two paragraphs. The author starts by informing us about great stuff regarding details of the outbreak date. We get symptoms, date ranges (1918-1920), the gargantuan figures of people affected, and the question of how scientists were left wondering why so many healthy adults were so easily susceptible. The author gives us a snippet of the answer, placing fault in the flu strain not properly being identified, which I felt left room for further elaboration on how vaccines and age groups tie together. This wasn’t a bad thing, as it left me looking forward to reading on.

However, to my surprise, as I reached the end of the second paragraph, I was back at square one. The author was once again telling me the ranges of affect, how researchers questioned why healthy individuals were so easily affected, and how it was due to ineffective vaccines. It was almost identical to how we were being told the first time and there was nothing new disclosed to justify the information coming back. It felt like the author was reaching to make it longer than necessary.

Cooper Dubrule

I really enjoyed the way this article goes about telling the story of influenza and how exactly it work as well as these efforts taken to stop or even slow it down. I like how it shows that even within the pass century we struggled with the containment of a disease, showing what a tough task creating an effective and safe vaccine may be.

Peter Coons

It has always fascinated me how humans always try to fight the course of nature. An illness exists, and we develop a means to combat it. However, it seems hubris in that tit-for-tat combat of man versus nature was knocked down a peg. By our own invention and science, we managed to kill millions of our species over what seems to be a simple clerical error. The most advanced species on the planet, taken out by someone who is not very skilled at data entry. This article is a great explanation of what early medicine was like, and how even with early vaccines, there was much we still did not know.

Kristy Feather

My mom is a nurse and so she has always been on top of my sister and I to make sure we go and get our vaccines done and I have to thank her every year because my friends who don’t get vaccinated, for either personal or religious reasons, always end up missing weeks of school due to catching the flu. Only instead of it only taking a few days to go away for those of us who are vaccinated, it takes weeks and hospitalization to fight the infection for them. THis article does a great job of highlighting the specific reasons why we need to get vaccinated and proves that in comparison to the past, our current health system is well adapted and equipped to take on outbreaks such as influenza.

John Smith

I imagine that humanity’s greatest enemy has been illness and disease. It’s no secret the number of plagues that the Earth has seen pass through its doors, so it’s no surprise that we could potentially have another flu epidemic someday. Bacteria and viruses are always evolving, so I suppose we’ll have to try our best to adapt to them as they adapt to us.